In the quest to sufficiently reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, it is crucial to “get the numbers right.” Failure to do so would, in all probability, mean that the desired reductions will not be achieved. Regrettably, much of what is being proposed is not based upon any comprehensive quantitative analysis, but is rather rooted in anti-suburban dogma.

Further, ideologically based approaches carry the risk of severe economic and social disruption, which could make it even more difficult, in a political world, to reach GHG emission reduction objectives. Unconsidered attacks on suburbs could also backfire, setting back more reasonable attempts to reduce emissions over time.

For example, a recent New York Times blog entitled “The Only Solution is to Move” presumed it a necessity to (1) move from the suburbs to the city, where (2) “you are near everything you need” and to (3) abandon cars, which the author contends “cannot be reformed.” This screed provides an ideal point of reference. We start with the comparative GHG emissions efficiency of suburbs and deal with the other issues in future articles.

The Need for Comprehensiveness: Any plausible attempt to reduce GHG emissions must start with a comprehensive understanding of the issue, including the comparative GHG intensity of various types of living and mobility patterns.

This requires a “top down” analysis of GHG emissions by mode and locality. Such an analysis must start with the gross GHG emissions in a nation and allocate each gram to a consuming household. A household allocation is necessary, because businesses emit GHGs only to satisfy the immediate or eventual demand of consumers. “Top down” is required because that is the only way to make sure the analysis includes everything. The typical “bottom up” analysis runs the risk of missing large amounts of emissions as analysts highlight their own “hobby horse” sources, while excluding the inconvenient. This is why we have “double entry” bookkeeping – to make sure that the sums balance.

“Top down” comprehensiveness has been best developed by the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) Consumption Atlas, which is the only study I have found that allocates every gram of GHG emissions in a nation to households. That is a minimum requirement.

Residential GHG Emissions

Having reviewed the need for comprehensiveness, the balance of this article will deal with residential GHG emissions. Despite all the airtime – and trees – sacrificed for lengthy columns on GHG emissions, it is clear that the state of the research in the United States remains abysmal.

GHG Emissions: A Function of House Size: Research has been published that suggests the dominant suburban housing form (the detached single-family dwelling) is more GHG intensive than more urban, multi-unit and high-rise apartment and condominium housing forms. However, the entire supposed city versus suburbs advantage relates to house size. The Department of Energy’s Residential Energy Conservation Survey (RECS) data shows that the energy consumption per square foot is 70 percent higher in residential buildings with five or more units (the largest building size reported upon) than in detached houses. Full disclosure on the part of the anti-suburban crowd would require telling people that their conclusions would mean much smaller house sizes.

Common Area GHG Emissions: There is, however, a far more fundamental problem. The databases usually relied upon (The Bureau of the Census’s PUMS and the Energy Department’s RCES), as cited in the USDOE 2008 Buildings Energy Data Book, do not provide sufficient information to demonstrate any high-density GHG emissions advantage.

None of these data sources include the GHG emissions from “common” energy consumption in multi-unit residential buildings. Their information is limited to energy consumption as directly billed to consumers. Thus, in a high-rise building, common energy consumption sources such as elevators, common area lighting, parking lot lighting, swimming pool heating, common heating, common water heating, common air conditioning, etc. are not included. Detached housing generally does not have common energy consumption.

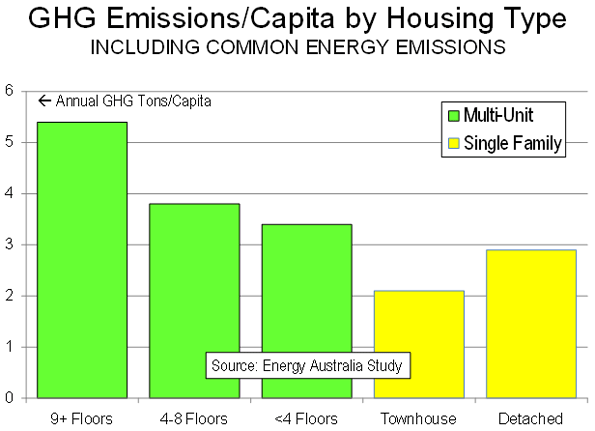

The “common” consumption omission is serious. Other Australian research indicates how inaccurate consumer based inventories can be. Energy Australia has showed that, in the Sydney area, GHG emissions per capita, including common consumption, in high-rise residential buildings are 85 percent greater than in single family detached dwellings. Other multiple unit buildings are also more GHG intensive, while townhouses (row houses) are the best (see Figure).

The inclusion of common consumption may be a principal reason why the ACF data associates lower GHG emissions with single family detached housing.

Construction Materials: There is a further complicating factor. The materials that must be used to construct high-rise residential buildings, chiefly concrete and steel, are far more GHG intensive than the wood used in most single family dwelling construction. A 1997 Netherlands study indicates that the GHG emissions per square foot of high rise construction may be as much as five times that of a detached dwelling. In the newest energy efficient housing, the same study finds that the GHG emissions, over a building’s lifetime, can be greater than the emissions from day to day operation. The report notes that construction materials will become more important in residential GHG emissions, because improvements in routine energy consumption are likely to be more significant than those in building materials production.

Then there is the issue of the GHG emissions in the construction process. It would not be surprising, for example, if heavy cranes could also tip the balance against high-rise towers.

Dynamic Rather Than Static Analysis: Anyone who has studied economics understands the importance of “dynamic” versus “static” analysis. Dynamic analysis takes account of likely changes, while static analysis assumes that everything will continue to be as it is today. Much of the research on residential GHG emissions is based upon a static analysis. Yet, the housing stock (like the automobile stock) was largely produced during a time when there was little policy incentive to reduce GHG emissions. We are entering what may well be a very different policy environment. The comparatively recent emphasis on GHG emissions is producing a plethora of ideas, research and solutions. A recent Chicago Tribune article noted a surge in university graduates interested in research to reduce the GHG intensity of energy. The zero emission suburban house is on the horizon, which could take housing form “off the table” as a GHG emission issue and render static research to the internet equivalent of rarely accessed library stacks. Dynamic analysis asks “what can be,” not just “what is.”

Cost per GHG Ton Reduced: All of this raises a question about how to identify policy strategies. The answer is to compare costs. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change suggests that the maximum costs should be on the order of $20 to $50 per ton. McKinsey has published research indicating that steep reductions can be produced in the United States at less than $50 per ton.

Yet, the costs of GHG emissions reduction are as absent from much of the present literature as the GHG emissions from elevators in high-rise towers. But costs are important. Economic and social disruption is likely to be greater to the extent that people are forced to change their lives. There is a big difference between requiring people to reduce their emissions where they live versus trying to uproot them – as well as their families and business – to urban cores. The former offers the hope of achieving sufficient GHG emission reductions, while the latter promises to incite a bitter fight between the bulk of the middle class and the regulatory apparatus. All this with a high probability that GHG emissions will not be sufficiently reduced.

The Bottom Line: Outside some in the urban planning community, there is no lobby for reducing people’s standard of living. At least with respect to residential development and housing form, this does not appear to be necessary. The common area and construction GHG impacts of high-rise condominium buildings could well be greater both per capita and per square foot than those of detached housing. There is no need to force a move into a futuristic Corbusian landscape of skyscrapers. Indeed, it could even make things worse – for households, communities and even the environment.

Previous posts on this subject:

Regulating People or Regulating Greenhouse Gases?

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Policy: From Rhetoric to Reason

Enough “Cowboy” Greenhouse Gas Reduction Policies