After a long period of stagnation, last week’s announcement of the first substantial annual income gains since 2007 was certainly welcome. Predictably, analysts inclined toward a more favorable view of President Obama’s policies reacted favorably. Progressive icon Paul Krugman crowed that last year the “economy partied like it was 1999,” which he said validated the president’s “trickle up economics.”

Equally predictably, conservative pundit Stephen Moore wrote that the stagnant longer-term numbers were actually a ”stinging indictment” of both the Obama and Bush records.

The reality may be in between. The 5.2% increase over the past year was the largest in the nearly 50-year history of the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, and does represent some progress. Yet real incomes remain approximately 2.5% below the 1999 peak. This is an extraordinarily long time for incomes not to have risen, a decade longer than the previous modern record (1989 to 1995), according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

And there are some reasons to be skeptical about the dramatic gains, as outlined in a virtually unprecedented report by the economist Gary Burtless of the generally left-leaning Brookings Institution. He suggests that the year-to-year increase may have been much less and that the CPS had been under-reporting annual income increases since 2003. John Crudelle of the right-leaning New York Post notes that recent CPS methodology changes could also have inflated the 2015 increase.

To be sure, there are no signs of an economic boom that will sustain income gains — the 1.1% real GDP growth in the second quarter is no indication of a miraculous recovery.

Nonetheless, real income gains were made last year, but they were not distributed evenly across the nation. We sought to assess the areas that did the best – and worst.

The media has spun the story as further evidence of suburban decline and the resurgence of dense, hip cities. The Wall Street Journal went so far as to point to the migration of “highly educated millennials” to downtown areas as a factor, something that simply could not be deduced from the data that was reported.

With more than 80% of millennials residing in the suburbs, this was heroic conjecture. Within metropolitan areas, CPS reports only “inside principal cities” and “outside principal cities.” The Census Bureau abandoned “central city” and “principal city” data more than a decade ago, in recognition of the fact that many suburban communities had become major employment hubs. As a result, principal cities include such low density, sprawling suburban behemoths as Mesa, Ariz. (Phoenix), Hillsboro, Ore. (Portland), Arlington, Texas (Dallas-Fort Worth), and, Anaheim, Calif. (Los Angeles). Simply put, the data does not support the assumption that hipster urbanism played a part in the one-year upsurge.

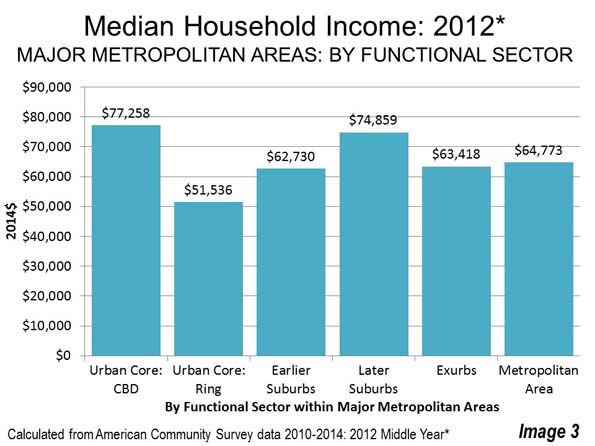

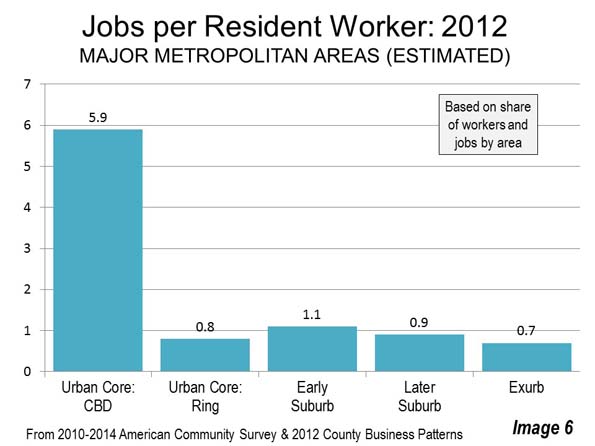

The numbers suggest a more nuanced picture. For one thing, downtown residents represent little more than 1% of our metropolitan population, and less than 10% of the jobs. Nor did the biggest income gains occur in the metropolitan areas with the large, elite urban cores. Indeed, it is hard to imagine results more at odds with theme of dense urban core gain and suburban malaise.

By far the largest gain was in Nashville, where household income rose 10.2% to $57,985. Nashville’s downtown is doing well, as is the case with many metropolitan areas. However, Nashville is hardly a model of the urban density planners would like to force around the nation. Its urban density is one-fourth that of nation-leading Los Angeles, a third that of New York and half that of Portland. The vast majority of its growth has taken place outside the core, and largely in the suburbs.

Perhaps most surprising is second-ranked, Birmingham, Ala. It is harder to imagine a more poorly performing metropolitan area in the rapidly expanding South, but last year household income there grew 9.4% to $51,459, according to the CPS data. Just after World War II, Birmingham was a third smaller than Atlanta; now Atlanta is five times as large. Nor does Birmingham set any density records. No metropolitan area the world with a population over a million has a lower urban area density.

Atlanta ranked third, with an increase of 7.2% to $60,219. The metropolitan area has the lowest population density among world urban areas with more than 2 million residents.

Other metro areas with suburban core cities in the top 10 include No. 5 Kansas City; No.7 Memphis, which could be argued has performed as poorly as Birmingham in recent decades; and No. 8 Orlando. None of these has an urban density much higher than the national average, which includes urban areas as small as 2,500 population. In 10th-ranked San Jose, the core of Silicon Valley, household income rose 5.7% to $101,980, the highest of any metropolitan area in the nation. It is a virtually all suburban metro area, having developed almost entirely since World War II, and among the most automobile oriented, with a miniscule 4% of commuters using its bus, light rail and commuter rail services. Milwaukee, another metropolitan area that has lagged economically for years, ranked ninth.

To be sure, the urban elites were not shut out. San Francisco, buoyed by spillover growth from suburban Silicon Valley, ranked fourth with a center that is the very definition of a dense urban core. Urban planning model Portland ranked sixth, yet it has an urban density 40% below that of all-suburban San Jose.

The nation’s three largest metropolitan areas did poorly. New York, ranked 39th, with income growth of 2.5%, well below the 5.2% national gain. Los Angeles, the nation’s densest region, grew slightly better, at 3.4%, but still ranked only 32nd; Chicago, the nation’s third largest ranked just above New York at 38th.

In last place is Oklahoma City, where, amid the oil and gas bust, household income dipped 0.4% to $52,221.

Thus, the story is not about media-favorite cities or their favored urban core, as the progressive punditry may suggest. The one-year spike is perhaps the first long overdue indication that things could be getting better for the struggling working class. The biggest gains were in poorer metro areas. It could signal, to some extent, higher wages as employment tightens, particularly at the lower end of the job spectrum.

Overall, it’s clear that even modest economic growth, sustained long enough, would bring some blessings to the poor, particularly in the inner cities. The question is whether these gains can be sustained in an economy where growth seems to trending slower still.

This piece first appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, will be published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international pubilc policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photograph: Downtown Nashville from BigStockPhoto.com