Gary Hustwit’s new film, “Urbanized,” is the third in his series of documentaries concerning design. In his first two films, he looks at consumer product design and the global visual culture. The existential problem of the city, an urgent one about which much of this website is concerned, is scarcely treated in our contemporary mainstream, and Hustwit’s effort is laudable. In this film, he tackles urban design, introducing ideas about how cities should – and should not – accommodate growth. “Urbanized” tends to favor the big idea over the small, and airs the conventional wisdom of the urban design community. In doing so, he brings to the public an important debate, but he misses some opportunities to explore change in the urban realm.

In a visual feast of a film, interlaced with intriguing interviews of some of the luminaries of the 21st century design culture, “Urbanized” makes a case for elevating the environment to the same level of concern as architecture and mobility. The documentary tends to reinforce, not question, notions of right and wrong growth that are promulgated by the urban intelligentsia, and he declines to explore the validity of most of these notions. He also tends to focus on large, dramatic solutions to the urban growth dilemma, perhaps because they make for good cinema. Flashy red Transmilenio buses in Bogatá; NASA-like control centers in Rio de Janiero; and Green Party clashes with the police in Stuttgart all imply that heroes must be at work to keep our cities livable and inspiring.

To his credit, Hustwit does show local and small changes that are taking place in cities like New Orleans and Detroit. He interviews urban agriculturalists, conceptual artists, and folks who spray-painted a graph of their power consumption on their street in Brighton, England. Small moves like these are important, and tell us about how people are coping with unique urban challenges today. But these stories are background to the larger profile stuff happening elsewhere on the globe.

In Santiago, Chile, “Urbanized” shows the viewer how affordable housing is being developed on highly desirable land close to jobs. The architect interviewed potential residents, giving them a choice between a water heater or a bathtub (all chose the bathtub, preferring to save up for the water heater). Recognizing employment value over land value is exactly the kind of brave step that is much needed in our cities today, and this project provides a bold experiment to watch in this regard. Even bolder is the strategy that assumes people, through their own devices, will prosper and increase the value of their home on their own – save up to buy a water heater, for example. The documentary provides an interesting glimpse into an alternative approach to housing in this segment.

Of course, no moviemaker could expect a good reception to a movie like this without paying homage to New York City, and Hustwit delivers us affectionate portraits of the Big Apple at the beginning, middle, and end of the film. With the recent transformation of the city’s old elevated rail bridge, the High Line, Hustwit nicely showcases environmental awareness, historic preservation, and sustainability. In a city that has effectively raised its hierarchy of needs to the ether, the issues of poverty and sanitation are worlds away.

Which, in fact, they are in this film. Over half the globe’s population lives in cities, so most—nearly one third of the globe’s population—live in urban slums. Hustwit exposes the pain of this reality. Edgar Pieterse of the African Center for Cities describes the horrific conditions of urban poverty, and in Mumbai, architects discuss the government’s obstinacy in addressing these conditions in this famous slum. Here, urban design is viewed as a strikingly pessimistic problem. Density without modern technology violates basic hygiene and human dignity; and there appears to be no solution.

The stereotype of Mumbai’s slums is reinforced, with a touch of Cape Town thrown in as well. Yet, one wonders if the contemporary desperation of urban poverty in Western cities might be worth looking at, too; the vicious manner in which the Western poor vandalize their own city and strike out at their fellow citizens seems to be perpetually ignored, while the relatively mild behavior of the Mumbai slum dweller seems all too pitiable when viewed large on the big screen. The poorest classes in the Western world, lacking access to education and upward mobility, are acutely aware of their neighbors’ material success, thanks to the ubiquitous media. For fifty years, this tension has wrecked our inner cities, but has been ignored by urban designers. “Urbanized” continues this trend.

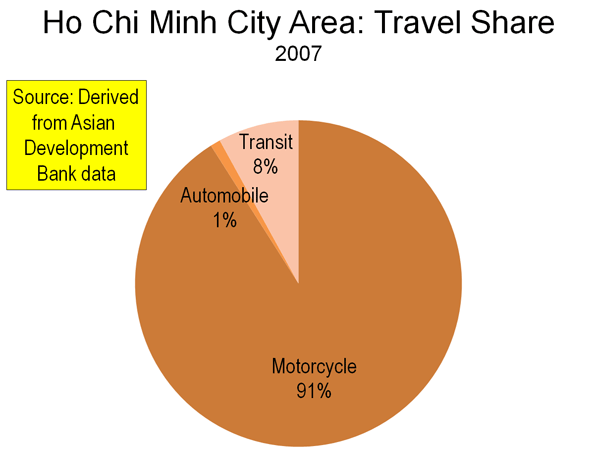

In the meantime, Hustwit interviews architects, urban planners, politicians, and academics who aspire to make cities walkable, compact, and connected. Within this community, the car is deemed as a painful problem, and “Urbanized” takes us from Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City to modern day Phoenix. The arc of the film begins with trains, and then showcases buses, cars, bicycles, and walking solutions. By now, it is ritual to condemn the car and rejoice in the other options, and “Urbanized” follows this formula.

Just as Mumbai is shorthand for slums, Phoenix is shorthand for sprawl. Footage of traffic jams suggest that Phoenix is a worst-case scenario, even though the longest commutes by far take place in denser regions, such as New York and Los Angeles. Again, “Urbanized” does slip in a small, but important point, using Grady Gammage, Jr., a real estate attorney, academic, and political leader in Phoenix. Gammage reminds the viewer that what is commonly labeled as “sprawl” is, in fact, the density level at which humanity has always dwelt.

“Urbanized” serves as a timely milestone, bringing together voices and ideas that dominate our thinking about cities today. While it deals with problems like the rebuilding of New Orleans, it also seems timeless by not mentioning some of the recent changes that affect our urban existence.

The global recession cooled off the credit market, which has paused construction in all but a few places. The impact this has had on our cities would be an interesting documentary to watch, for our built environment is much like a consumer product, as buildings go quickly obsolete and competition forces building owners to keep up. Nimble private developers have already switched gears to repair and renovate; yet our municipal codes, fees, and processes are still geared to the boom. This schism between private and public thinking is constraining our cities today.

Affordable housing will sharply affect urban life in the near future, and western cities seem to be on a trajectory that increasingly looks headed towards Mumbai. Ignoring the gap between the rich and the poor and heaping requirement upon requirement until prosperity is all but lost to the poor could negatively affect our cities.

The last time city planning was earnestly discussed at the mainstream level was perhaps in Jane Jacobs’s heyday in the early nineteen sixties. Since then, the arguments and theories seem to have been put away, having solved the problem at the time, and new solutions have not been eagerly considered. These solutions – born in the righteous indignation of Jane Jacobs’s – are a bit shopworn. Much has changed since the 1960s: Our population has increased by an order of magnitude; urban dwellers outnumber rural, and our image of the city has changed. We acquired an internet. It is time to take stock.

The debate about how our cities will grow in the 21st century must reach the mainstream, and get out of academia and the professional specialists. “Urbanized” is a timely examination of the problems of the city today – how to provide a sanitary and dignified urban form at the basic level, and how to inspire and rejoice in the sheer spectacle of the city at a higher level. It has started to relight the much-needed fires of debate and conversation among citizens of cities today.

Richard Reep is an Architect and artist living in Winter Park, Florida. His practice has centered around hospitality-driven mixed use, and has contributed in various capacities to urban mixed-use projects, both nationally and internationally, for the last 25 years.