The Durban climate change conference has come to an end, with the nations of the world approving the "Durban Platform," (Note 1) an agreement to agree later on binding greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets by 2020. The New York Times reported: "Observers and delegates said that the actions taken at the meeting, while sufficient to keep the negotiating process alive, would not have a significant impact on climate change."

Not surprisingly, not all are pleased by the largely toothless agreement. Nnimmo Bassey, chair of Friends of the Earth international, told The Guardian:"Delaying real action till 2020 is a crime of global proportions." Todd Stern, the United States representative, signed on to the deal but noted that "there is plenty the US is not thrilled about."

There is general agreement that any program to reduce GHG emissions must do so in the most efficient (least expensive) manner. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has concluded that sufficient emissions reductions can be achieved for between $20 and $50 per ton. Any cost above that must be considered wasteful and likely to reduce economic growth, while increasing poverty.

Yet, researchers often leap from identifying a strategy to reduce GHG emissions to recommending its implementation, without ever examining the cost.

Often missed for instance, is that reductions in some sectors may prove less expensive than in others. The European Conference of Ministers of Transport has noted that "It is important to achieve the required emissions reductions at the lowest overall cost to avoid damaging welfare and economic growth." Across-the-board targets would misallocate resources, unnecessarily reducing economic growth and increasing poverty. This is particularly important in transport, because IPCC data indicates the potential for cost effectively reducing GHG emissions from this sector is considerably less than its contribution to emissions.

GHG Emissions from Automobiles: In the United States and other high income nations, however, mandates are being pursued that would impose far higher costs. Our new report, published by the Reason Foundation, Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Automobiles reviews two general approaches. The first is behavioral approaches, the favorite of policymakers, that would force people to leave the suburbs to live in higher densities ("compact city" or "smart growth" policies) and discourage personal mobility. The second is facilitative approaches, which would reduce GHG emissions through technological advances, minimizing the necessity for command and control mandates over people’s lives.

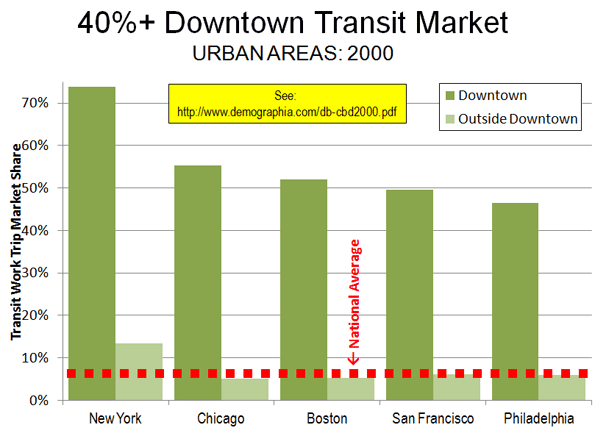

Behavioral Approaches: In what passes for the conventional wisdom, current thinking would require densification for virtually all new development, while trying to force people out of cars to travel by transit, bicycle or walking, all characterized as "sustainable" transport modes. Further, these strategies would seriously impede personal mobility by increasing travel times and reducing access to employment. This reduction in accessibility to jobs would be a backward step for any nation interesting in longer term economic growth (Note 2).

The behavioral strategies are described in two principal US reports: Driving and the Built Environment which was produced by the National Research Council and Moving Cooler, by a consortium of organizations led by the Urban Land Institute and Cambridge Systematics. Each of these reports provides detailed estimates of the GHG emission reductions to be expected from land-use and mass transit strategies by 2050 in the United States.

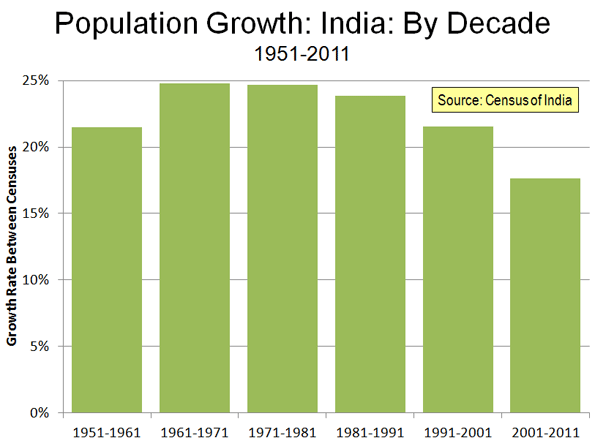

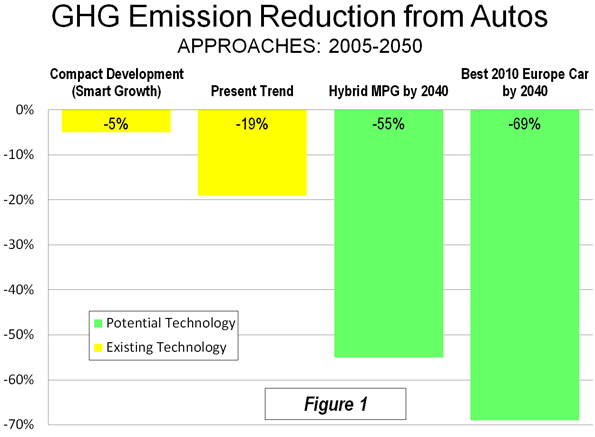

The reductions are relatively modest, averaging less than 5% from the early 2000s to 2050 . Driving and the Built Environment indicates that the drafters did not agree its most aggressive scenario was achievable. Moving Cooler was soundly criticized by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials and on these pages by leading transport consultant Alan E. Pisarski (see: ULI Moving Cooler Report: Greenhouse Gases, Exaggerations and Misdirections).

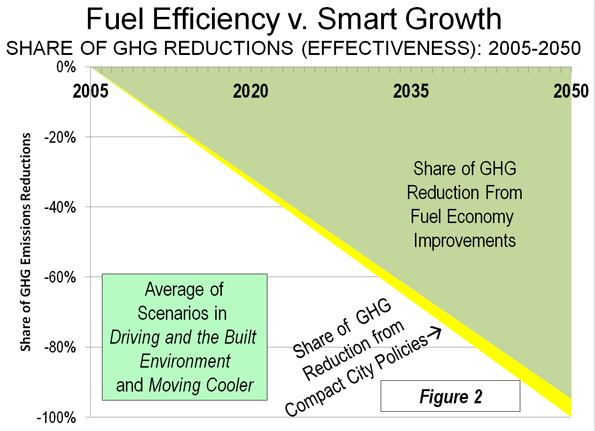

These proscriptive policies focus on housing and land use even thought nearly all of the improvement in GHG emissions would result from automobile fuel economy improvements, not compact city policies. Depending upon the scenario, between 89% and 99% of the reduction in GHG emissions from cars by 2050 (Figure 1) would be the result of fuel economy improvements, rather than from compact city policies (based on comparison base year, early 2000s, fuel economy).

Moreover, even the modest 1% to 11% reduction (5% average) in GHG emissions due to compact city policies are likely high because of greater traffic congestion, which neither report considers. Higher density urban areas, such as compact city policies would require, would spark greater traffic congestion. This means that cars travel slower and in more erratic traffic conditions. This, ironically, increases fuel consumption and GHG emissions per mile or kilometer. Thus, as noted here before, under these policies, GHG emissions from cars could actually increase.

Neither Driving and the Built Environment nor Moving Cooler report considers the economic impact of compact city land rationing, which drives up housing prices and could thus be expected to impose higher costs on households. The economic literature is virtually unanimous in associating higher land and thus house prices with smart growth type land rationing policies. The increased costs could be many times the IPCC $20 to $50 per ton of GHG emissions removed.

Even the popular assumption that suburban housing produces materially greater GHG emissions is questionable. Most US research fails to capture the common GHG emissions from elevators, heating, air conditioning, lighting, etc. in larger multi-unit housing, which are costs attributed to the building itself (landlord or condominium building) as opposed to household energy bills (simply because there are no data). Yet, research in Australia indicates that common GHG emissions render higher density multifamily housing more GHG intensive than either townhouses or detached housing. Also escaping many researchers is the fact that carbon neutral housing is being developed, which could remove any GHG emissions differences between housing types.

Compact city or smart growth policies have little potential to reduce GHG emissions and would do so at exorbitant costs that are well beyond those identified by the IPCC. This is not surprising, since compact city and smart growth policies have been widely touted long before the general concern over climate change. Denser cities have been pushed as a means to improve “community,” spur economic efficiency, reduce air pollution and deal with such ephemeral – given recent massive energy finds – notions of “peak oil”.

Facilitative Approaches: Any achievable program to reduce GHG emissions must be multi-dimensional and focus primarily on achieving that goal in the most economically and socially beneficial manner and not be based upon tired policies designed long ago to serve other agendas. There is no need for expensive and draconian compact city approaches. A report by McKinsey and the Conference Board concluded that substantial and cost effective GHG emission reductions were possible, “while maintaining comparable levels of consumer utility,” which was defined as “no change in thermostat settings or appliance use, no downsizing of vehicles, home or commercial space and traveling the same mileage.” In other words, there is no need to interfere with people’s lives or preferences (Note 3).

The most promising approaches involve improvements in fuel economy. For example, Volkswagen has developed a two-seater car that achieves 235 miles per gallon (US) of gasoline or petrol (1 liter per 100 kilometers). With current fuel economy averaging little over 20 miles per gallon (12 liters per 100 kilometers) in the United States, the frontiers of fuel economy improvement have barely been approached.

Moreover, substantial GHG emissions reductions can be achieved at levels far below 235 miles per gallon. The United States Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasts that even if driving increases 29% from 2005 to 2025, GHG emissions from cars would be reduced by 7% (Note 4). If, as is demonstrably possible, the EIA forecast fuel efficiency improvements were to continue to 2050, the reduction would be 19%, despite an increase in driving of more than 60%. At a slower driving growth rate more consistent with more recent trends, the reduction could be 33% (Figure 2).

Further, if the US light vehicle fleet (cars and sport utility vehicles) were to achieve the current fuel economy performance of the best hybrid vehicles, the reduction in GHG emissions would be between 55% and 64% by 2050. Matching European performance forecasts would reduce GHG emissions even more.

A substantial increase in the fastest growing sector of commuting, working at home (often telecommuting), could also help. Nothing can cut emissions more thoroughly than working at home, which produces zero GHG emissions. Yet, this innovation – which already surpasses transit use in most American metropolitan areas – inexplicably receives little or no attention from planners intent on herding people into higher densities and travel modes that take longer.

The great advantage of facilitative approaches is that, as the McKinsey-Conference Board report indicates, people are permitted to live their lives as they prefer even as emissions are reduced.

The Dimensions of Sustainability: Perhaps the greatest problem with behavioral approaches is that they may not be sustainable at all. Sustainability is multi-dimensional. Compact city and smart growth policies lack financial sustainability because they spend far too much per ton of GHG emissions. They lack economic sustainability because they would impose substantially higher costs, especially on housing prices. Ultimately, unless humans radically change their demonstrated preferences, compact city and smart growth policies may not be politically sustainable because people are likely to resist them either at the ballot box, or by moving – as demonstrated in the latest census – even further out from the urban core or to smaller, less regulated and less dense regions. All three dimensions of sustainability, financial, economic and political, must be prerequisites to material GHG emissions reductions.

Notes:

(1) Reuters provides an early summary of the Durban Platform.

(2) The strong connection between economic growth and minimizing urban travel times is identified in research such as by Prud’homme and Lee at the University of Paris and Hartgen and Fields at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte.

(3) The McKinsey-Conference Board report was co-sponsored by Shell, National Grid, DTE Energy and Honeywell, as well as environmental advocacy organizations, the Environmental Defense Fund, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC),

(4) Proponents of compact city policies sometimes claim that fuel efficiency improvements cannot reduce GHG emissions because the increase in driving neutralizes their impact. EIA projections indicate otherwise, as is shown here.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

Photograph from BigStockPhoto.com

Many US politicians recoil against the state as a real estate developer largely because tenanted housing projects have been such a magnet for social problems. The St. Louis public housing scheme, Pruitt-Igoe, was eventually dynamited (see photo right

Many US politicians recoil against the state as a real estate developer largely because tenanted housing projects have been such a magnet for social problems. The St. Louis public housing scheme, Pruitt-Igoe, was eventually dynamited (see photo right