This is the introduction to a new report, "The New World Order" authored by Joel Kotkin in partnership with the Legatum Institute. Read the full report and view the maps at the project website.

The fall of the Soviet Union nearly a quarter of a century ago forced geographers and policy makes to rip up their maps. No longer divided into “west” and “east”, the world order lost many of its longtime certainties.

In our attempt to look at the emerging world order, we have followed the great Arab historian Ibn Khaldun’s notion that ethnic and cultural ties are more important than geographic patterns or levels of economic development. In history, shared values have been critical to the rise of spheres of influence across the world. Those that have projected power broadly – the Greek, Roman, Arab, Chinese, Mongol and British empires – shared intense ties of kinship and common cultural origins. As Ibn Khaldun observed: “Only tribes held together by a group feeling can survive in a desert.”

Of course, much has been written about the rising class of largely cosmopolitan “neo nomads”, who traipse from one global capital to another. But, for the most part, these people largely serve more powerful interests based on what we may call tribal groupings: the Indian sphere of influence, the Sinosphere and the Anglosphere.

Our approach departs from the conventional wisdom developed after the Cold War. At that time it was widely assumed that, as military power gave way to economic influence and regional alliances, the world would evolve into broad geographic groups. A classic example was presented in Jacques Attali’s Millennium: Winners and Losers in the Coming World Order. Attali, a longtime advisor to French President Francois Mitterrand, envisioned the world divided into three main blocs: a European one centered around France and Germany, a Japan-dominated Asian zone, and a weaker United States-dominated North America.

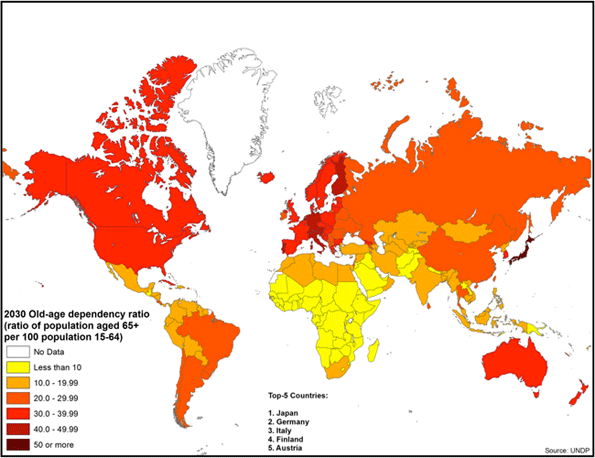

Time has not been kind to this vision, which was adopted by groups like the Trilateral Commission. The European Union proved less united and much weaker economically and politically than Attali and his ilk might have hoped. The notion of Japan, now rapidly aging and in a twodecades long slump, at the head of Asia, seems frankly risible. Although also suffering from the recession, North America over the past quarter century has done better in terms of growth and technology development, and has more vibrant demographics than either the EU or Japan.

More recently, attention has turned to the rise of the so-called BRIC countries – Brazil, Russia, India and China. Yet it turns out that these countries have even less in common than the squabbling members of the European Union. For one thing, they represent opposing political systems. Brazil and India are chaotic but entrenched democracies, for example; Russia and especially China remain authoritarian, one-party dictatorships.

These economies also are not particularly intertwined. Brazil is a major food exporter; Russia’s economy revolves around energy and minerals; China dominates in manufacturing; and India is vaulting ahead based largely on services. Brazil’s leading export markets, for example, are the United States and Argentina; Russia and China constituted together take barely 8 percent of the country’s exports. China’s largest trading partners by far are the United States, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. India ranks only ninth and Brazil tenth.

More important still, no common “tribal” link, as expressed by a shared history, language, or culture unites these countries and peoples. This link is fundamental to any powerful and long-lasting power grouping.

In contrast, the Indian and Chinese spheres, for example, are united by deep-seated commonalities: food, language, historical legacy and national culture. A Taiwanese technologist who works in Chengdu while tapping his network across east Asia, America, and Europe does so largely as a Chinese; an Indian trader in Hong Kong does business with others of his “tribe” in Africa, Great Britain and the former Soviet Republics in east Asia. Beyond national borders, these spheres extend from their home countries to a host of global cities, such as Hong Kong, Singapore, London, New York, Dubai, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, where they have established significant colonies.

The prospects for the last great global grouping, the Anglosphere, are far stronger than many expect. Born out of the British Empire, and then the late 20th Century, the Anglosphere may be losing its claim to global hegemony, but it remains the first among the world’s ethnic networks in terms of everything from language and global culture to technology. More than the Indian Sphere and Sinosphere, the Anglosphere has shown a remarkable ability to incorporate other cultures and people.

In the future, we will see the rise of other networks, as well. An example would be the Vietnamese sphere of influence, which reflects both the rise of that particular Asian country, and the influence of its scattered diaspora across the world. Culture is key to understanding the Vietnamese sphere: the country’s history includes long periods of Chinese domination that made it resistant to being absorbed into the Sinosphere. Instead, as we argue, Vietnam is likely to be more closely allied, first and foremost, with the United States and its allies.

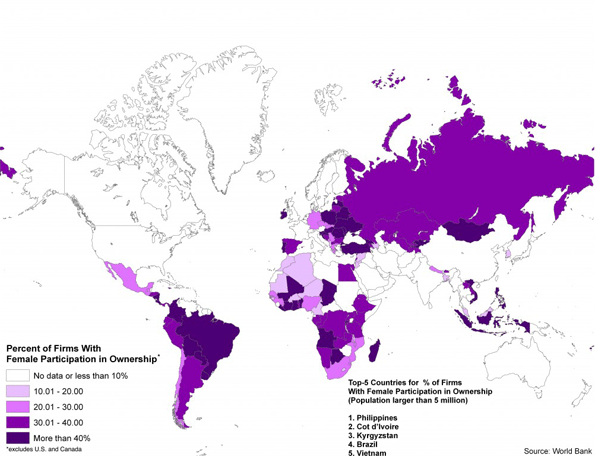

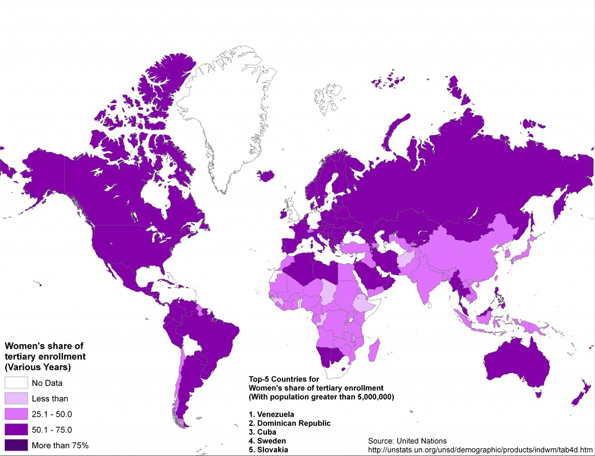

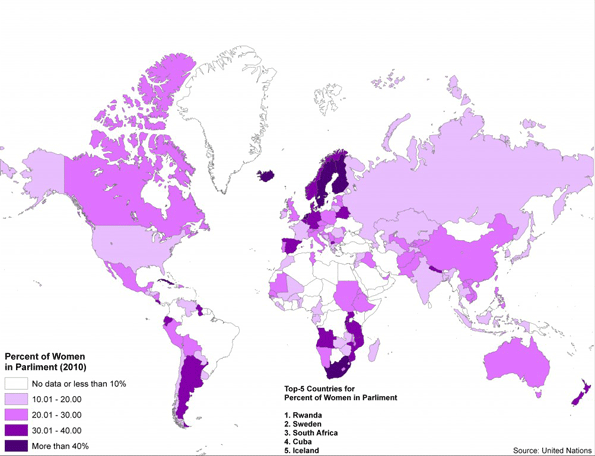

Finally, our maps deal with basic demographic issues that will dominate the future. We trace the global rise of women to prominence in business, education and politics. Although Western nations still lead in female empowerment, we argue that the most significant changes are taking place in developing countries, notably in Latin America. It will be these women – in Sao Paolo, Mumbai, and Maseru – who increasingly will shape the future female influence on the world.

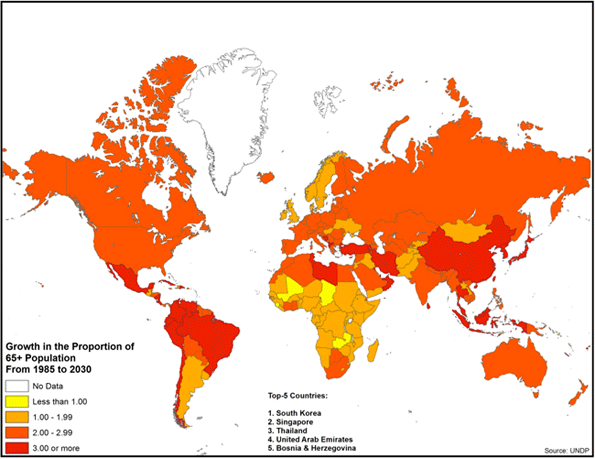

Yet this positive development also contains the seed of dangers. Female empowerment, along with urbanization, has had a depressing effect on fertility rates, seen first in the highly developed countries, and now increasingly in developing ones. Looking out to 2030, many countries, including the United States and China, will be facing massive problems posed by too many seniors and not enough working age people.

As has always been the case, the emerging world order will face its own crises in the future, with, no doubt, unexpected, unpredictable results. But our bet is solidly on the three spheres of influence which constitute the bulk of this report.

For the full report, visit The New World Order website at the Legatum Institute.

Report authors:

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and an adjunct fellow of the Legatum Institute in London. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010.

Sim Hee Juat is currently a research associate with the Centre for Governance and Leadership at the Civil Service College of Singapore.

Shashi Parulekar is an engineer by training. He holds a master’s in finance and an M.B.A. He has worked as a high-tech marketer in Asia for several decades.

Jane Le Skaife is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Davis. She is currently conducting her dissertation research involving a cross-national comparison of Vietnamese refugees in France and the United States.

Wendell Cox is a consultant specialising in demographics and urban issues, principal of Demographia and a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris.

Emma Chen is a senior strategist at the Centre for Strategic Futures, Singapore. The views expressed within this article are solely her own. Publication does not constitute an endorsement by the Centre for Strategic Futures, Singapore.

Zina Klapper is Deputy Editor of www.newgeography.com. A Los Angeles-based writer/editor/consultant with a background in journalism, she works in multiple aspects of report presentation. The maps were prepared by Ali Modarres, Professor of Urban Geography at California State University, Los Angeles.

We also owe a debt to our largely volunteer research staff, headed by Zina Klapper, Editor and Director of Research. This includes Gary Girod and Kirsten Moore from Chapman University, to whom we owe a special debt for directed study focused on the maps. We also wish to thank Sheela Bonghir from California State University at Northridge; Malcolm Yiong and Jasmin Lau at the Centre for Strategic Futures, Singapore, and Chor Pharn Lee at the Ministry of Trade and Industry and researcher Erika Ozuna, based in Dallas, Texas. Special thanks to Nathan Gamester at Legatum Institute in London for helping put this project together and seeing it to fruition.