As the American economy struggles to recover, its greatest advantage lies with its diverse population. The U.S.’ major European competitors — Germany, Scandinavia, France, Italy, the Netherlands and Italy — have admittedly failed at integrating racial outsiders. Its primary Asian rivals, with the exception of Singapore, are almost genetically resistant to permanent migration from those outside the dominant ethnic strain.

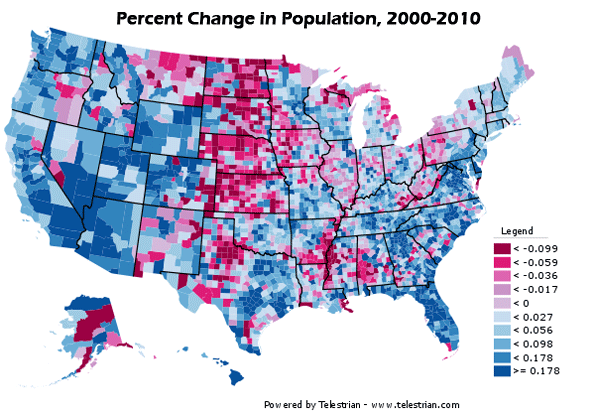

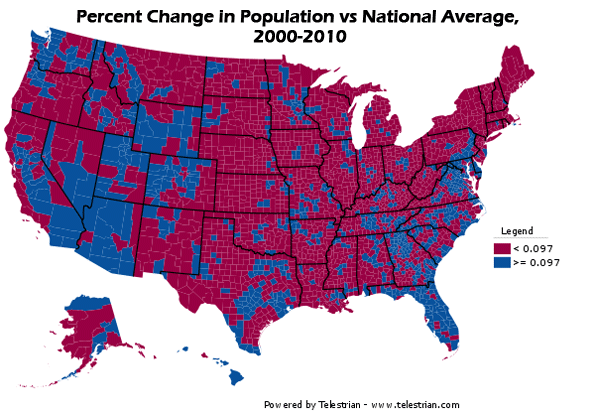

In contrast, America’s destiny is tied to minorities, who already constitute a third of the nation’s population and who will account for roughly half of the population by 2050. Younger and more heavily represented in the labor force, minorities are poised to become the primary source of entrepreneurial growth.

The clear advantage with minorities, particularly immigrant minorities, lies in their own self-selection. Risk-takers by the very act of emigration, they are more likely to start small firms than other Americans. In fact, a recent Kauffman Foundation study found that immigrants were unique in boosting their entrepreneurial activities since the onset of the recession. Overall the share of immigrants among new entrepreneurs has expanded from 13.4% in 1996 to nearly 30% this year.

Forbes asked demographer Wendell Cox (www.demographia.com), researcher Erika Ozuna and me to examine the immigrant entrepreneurial phenomena among the nation’s 52 largest metropolitan areas. The results (below) turned out to be in many ways surprising, and almost counter-intuitive.

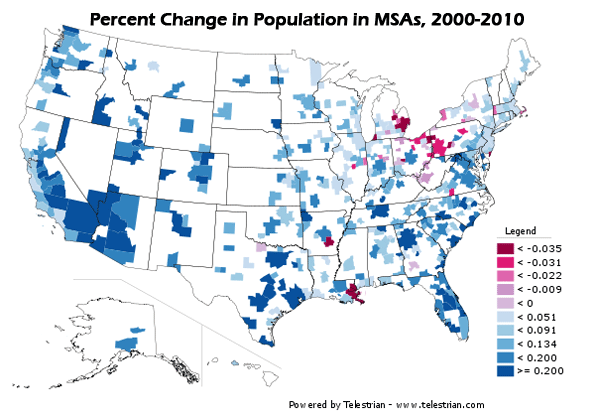

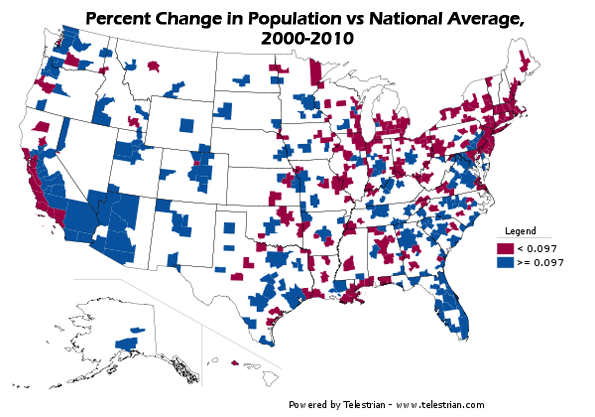

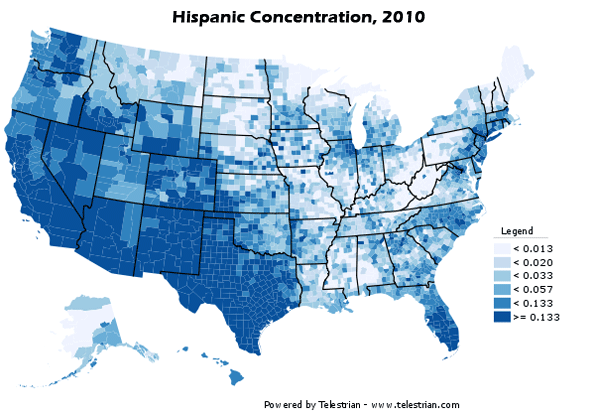

Usually we think of immigrant entrepreneurs as clustering in crowded city communities or high-tech places like Silicon Valley. But based on rates of self-employment, housing affordability, income growth and migration, immigrant entrepreneurs tend to prefer sprawling, heavily suburbanized regions, many of them clustered in the South and Southwest.

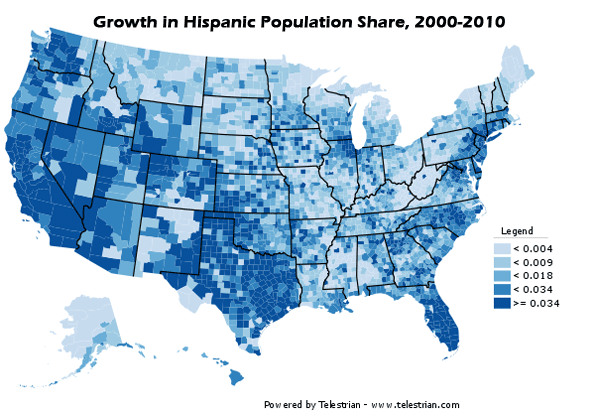

The best U.S. city for minority entrepreneurs on our list, Atlanta, has long been a haven for black entrepreneurs. But, recently, its Latino and Asian populations have exploded, with exceptionally high rates of self-employment. In the past decade, the Atlanta region’s Asian population surged 74%, while its Latino population grew by 101%. The overall foreign-born population rose by roughly 300,000.

Similar surges took place in almost all the top cities on list. They include Baltimore (No. 2), Nashville (No. 3), Houston, Miami, Oklahoma City, Riverside San Bernardino, Calif., the Washington D.C. metro area, Orlando, Fla.. and Phoenix, Ariz.

Latino shopping center developer Jose Legaspi traces much of the entrepreneurial success in these areas to this rise in population. This is particularly true in places like Miami, which has the nation’s highest rate of foreign immigration, and has long boasted of its role as “the capital of the Americas.” Less renowned are cities like Houston, which now enjoys a higher per capita rate of immigration than Boston, Seattle or Chicago. All these cities have engendered dense pockets of diverse and often dispersed ethnic populations; in some locales, ethnic groups share neighborhoods and economic space. It’s increasingly common to see stores owned by ethnic groups serving both their own tribe as well as others.

“The entrepreneurial class will follow the immigrant population,” notes the Montebello, Calif.-based entrepreneur, who has developed retail centers in such diverse locations as Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Atlanta, Phoenix and Fort Worth, Texas. “You get small retailers following their needs as well as a growing professional class.”

Legaspi notes that an increasingly critical factor for the growth of many of these fastest-growing minority areas is cost of living. With the exception of Baltimore and Washington — whose growth is tied to the expansion of the federal government — the cities on our list enjoy relatively low housing costs. Minorities “American dream” generally does not revolve around an apartment in dense, expensive urban areas, Legaspi n says, but want an affordable single-family house.

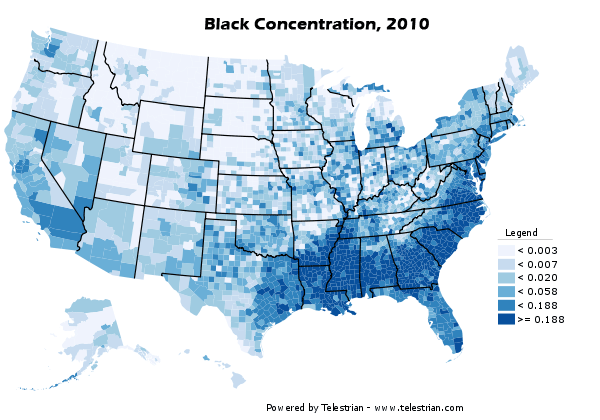

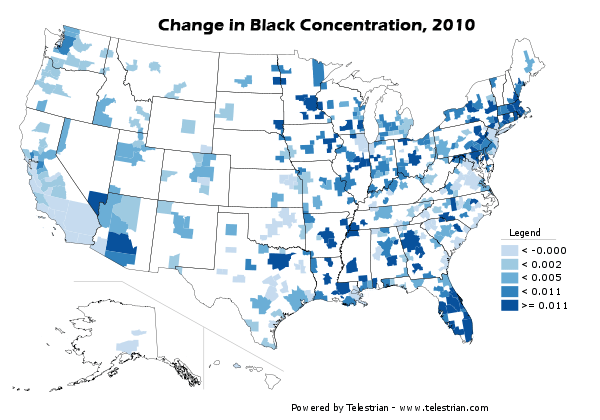

This also applies to middle- and working-class African-Americans, whose shift away from cities to suburbs has been among the most remarked upon phenomena identified by the Census. In Atlanta, for example, the ratio of median income to median house value is 4.6 for African-Americans, 3.1 for Asians and 5.2 for Hispanics. In 35th-ranked San Francisco it’s 14.3 for African Americans, 7.1 for Asians and 10.6 for Hispanics. No surprise that per-capita minority growth is far more rapid in Atlanta than in the avowedly “multi-cultural” Bay Area.

Land use and other regulations also play a role here, not only for housing prices but for entrepreneur opportunities. Again, with exception of the Washington and Baltimore areas, the fast-growing minority regions, and rapidly growing self-employed populations, are regions with diffuse, multi-polar and heavily suburbanized land patterns.

The strip mall, much detested among urban aesthetes and planners often serves as “the immigrants’ friend,” says Houston architect Tim Cisneros. In places like Houston, Cisneros points out, Columbians, Nigerians, Mexicans , Indian and Vietnamese businesses usually cluster not in downtown centers or fancy high-end malls, but in makeshift auto-oriented strip centers, where prices are low, parking ample and the location within easy driving distance of various ethnic populations. You want a good Indian meal in Houston, you don’t need to head downtown, but to the outer suburbs of Fort Bend County.

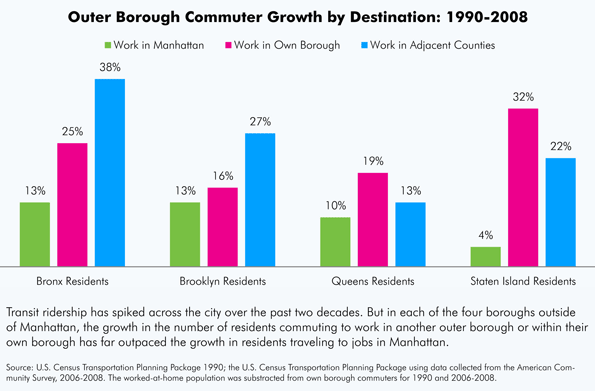

In contrast, many of the more expensive, denser regions — many with storied high-tech sectors — did poorly in our survey. Besides San Francisco, Minneapolis ranked No. 49, San Diego No. 48, San Jose No. 46 and Boston No. 45. Chicago clocked in at a dismal No. 50.New York, the legendary home of minority entrepreneurship, ranked a meager No. 39.

Jonathan Bowles, president of the New York-based Center for an Urban Future, traced this poor performance to a myriad of factors, including sky-high business rents, which stymie would-be entrepreneurs in minority communities. “[Entrepreneurs] face incredible burdens here when they start and try to grow a business,” Bowles suggested. “Many go out of business quickly due to the cost of real estate and things like high electricity costs. It’s an expensive city to do business without a lot of cash.”

Yet not every region at the bottom of our list came from the array of high-end “luxury” cities. The bottom of the list also included a host of rustbelt cities, including Detroit (No. 47), Cleveland (No. 51) and Milwaukee (last place at No. 52). Clearly cheap rents and affordable space are not enough when weighed against slow job growth, weak immigration and general economic stagnation.

And often, notes Richard Herman, an immigrant attorney in Cleveland, a cultural pre-disposition against immigrants plays a destructive role in many of these cities. “The rust belt cities don’t tend to welcome newcomers,” Herman says. “The infrastructure, the sentiment is not there. But you can’t get around it. We have to change our culture if want to change our situation.”

Here is the full ranking of the top 52 metros for minority entrepreneurs, compiled by researchers Wendell Cox and Erika Ozuna:

- Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA

- Baltimore-Towson, MD

- Nashville-Davidson-Murfreesboro-Franklin, TN

- Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown, TX

- Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach, FL

- Oklahoma City, OK

- Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA

- Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV

- Orlando-Kissimmee, FL

- Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, AZ

- Memphis, TN-MS-AR

- Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX

- San Antonio, TX

- Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL

- Austin-Round Rock, TX

- Charlotte-Gastonia-Concord, NC-SC

- Indianapolis-Carmel, IN

- Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana, CA

- Richmond, VA

- New Orleans-Metairie-Kenner, LA

- Jacksonville, FL

- Tucson, AZ

- Portland-Vancouver-Beaverton, OR-WA

- Raleigh-Cary, NC

- Louisville-Jefferson County, KY-IN

- Birmingham-Hoover, AL

- Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA

- Cincinnati-Middletown, OH-KY-IN

- Sacramento-Arden-Arcade-Roseville, CA

- Pittsburgh, PA

- Kansas City, MO-KS

- Columbus, OH

- Las Vegas-Paradise, NV

- Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC

- San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont, CA

- Denver-Aurora-Broomfield, CO

- St. Louis, MO-IL

- Buffalo-Niagara Falls, NY

- New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA

- Rochester, NY

- Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT

- Salt Lake City, UT

- Providence-New Bedford-Fall River, RI-MA

- Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD

- Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH

- San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA

- Detroit-Warren-Livonia, MI

- San Diego-Carlsbad-San Marcos, CA

- Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MS-WI

- Chicago-Naperville, Joliet-IL-IN-WI

- Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor, OH

- Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI

This piece originally appeared in Forbes.com

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and an adjunct fellow of the Legatum Institute in London. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, released in February, 2010.

Photo by LHOON