A critical issue from the dreadful earthquake that has severely damaged so much of central Christchurch, taken so many lives, and terrified so many residents of the whole urban area, lies in whether the Central Area should be rebuilt. Some believe it should be abandoned for some other location; others see an opportunity to set new standards in sustainability, urban design, energy efficiency, or whatever ideal urban form takes your fancy.

Let’s put the issue of “sustainable cities” to one side because the can words means anything, and hence mean nothing. It has become one of the most overused phrases in the English language.

Not surprisingly, Many of Auckand’s leaders are thrilled by the recent official ranking of Auckland as the tenth most livable city in the world, and have announced their determination to make Auckland even more “liveable” than it is now. This target of livability is also surfacing in Christchurch, normally to bolster demands for urban rail, transit-oriented gentrification, promoting cycling and walking, and making the city attractive to the “creative class”.

However this quote from a US urban blog should give the livability boosters pause:

Much of the highly touted livability of Portland has come at the expense of making it unlivable, that is, unaffordable, to anyone without a six figure income. The creative and professional classes thrive in Portland because they are the only ones who can afford it, and they are the ones who appreciate the development style the city has tried to mandate.

I first raised this issue of ‘rich folk’s livability’ in How Can Cities With Unaffordable Housing Be Ranked Among The Most Livable Cities In The World? here on NewGeography. Then Wendel Cox further quantified such city’s “unlivable reality" in Unlivable Vancouver, in NewGeography.

Cities designed to be sustainable or livable are likely to be unaffordable for all but a few.

The Case for Resilient Cities

Many of us watched the devastation caused by the floods in Queensland, Australia, driven by major rainstorms inland, and Pacific Typhoons devastating the West Coast and the hinterlands. The combination of a strong El Nina with the Pacific Decadal Oscillation means such events will be more common and more extreme in this part of the world than we have become used to since the similar combination of 1917/18.

However, Phil McDermott, on his blog Cities Matter was quick to comprehend the lessons to be learned by our political leaders and urban planners.

He opens his blog comment Cities in Search of Resilience with:

An age of extreme events?

Without debating whether an increase in the frequency of extreme events reflects climate warming, such events can be catastrophic when they impact on densely populated areas. Natural disturbances, whether geophysical (tsunami, earthquakes, mudslides) or climatic (flooding, hurricane strength winds, tidal surges), become disasters if they strike heavily populated centres.

So do human acts of aggression. The tactic of terrorising civilian populations taken to new heights in the bombing raids of the Second World War and adopted by today’s extremists is most effective – and destructive – when directed at the heart of major cities.

Later in the post Phil sets out the following vulnerabilities generated by the current "compact city" planning paradigm:

It relies on sophisticated, centralised interdependent systems of services. This creates greater capacity for disruption when any one part fails. Economies of scale in utilities may come with increased risk of failure under duress. This applies to sewage treatment infrastructure, communications, water, energy distribution, and power supplies. It also applies to public transport systems.

Poorly designed intensification reduces permeable surfaces, intensifying flood impacts.

Converting brownfield and even greenfield sites (such as undeveloped urban space) to housing or mixed use reduces the safety valve of open space and increases vulnerability associated with the concentration of buildings and populations.

Crowding more people into smaller spaces around constrained road capacity reduces prospects for rapid evacuation from the city or into safe structures and areas.

Lifting the density of buildings increases the consequential impacts of severe events by such things as the collapse of structures, the spread of fire, and the transmission of disease.

Read the whole post here. You might think Phil was setting out a list of lessons to be learned from Christchurch – but that "extreme event" was still in the future. A few days later, Phil responded to this tragedy with a second blog post, that picked up the same theme, titled "A Cruel Blow to a Beautiful City" which offers this timely warning:

We cannot resist the power of earthquakes, hurricanes, tsunami, and the like. But we can perhaps limit the devastation that accompanies them.

The implosion of many of Christchurch’s beautiful heritage buildings is a tragedy on its own, the wiping from the landscape of much of the City’s and nation’s history. But seeing the collapse of more modern buildings is sobering.

What are the lessons of architecture and engineering that might be drawn from this?

How much resistance can we realistically build into our structures? Or should we be thinking less rigidly, and explore designs that deflect or reduce the impacts when buildings are faced with irresistible forces? Should we think more about the survival of the people in and around buildings and less about the survival of the structures? Are there innovations in design that offer refuge, protection, and escape even if walls crumble and floors collapse?

This event in Christchurch must surely erode planners’ resistance to the decentralisation that is the mark of a prosperous, modern city, that makes it that little bit more liveable, and so much more resilient in the face of disaster?

Surely, Hurricane Katrina, and these events in Australia and New Zealand suggest that planners should stop worrying about sea level rises that MIGHT, or might not, happen in 100 years – with plenty of warning – and start thinking more about making our cities resilient in the face of catastrophic events which we know can happen tomorrow – hurricanes, cyclones, blizzards, volcanoes, earthquakes and tsunami.

However, the proper debate should not be as simple-minded as "high rise vs. low rise" or "old vs. modern". In Christchurch, liquefaction contributed to the collapse of some of the modern buildings. In the Kyoto earthquake some robust high-rise blocks simply fell over, because of the total collapse of the ground under the building, but remained in one piece.

Such problems and issues are not solved by sets of simple rules but by the application of skill, experience and wisdom.

Owen McShane is Director of the Centre for Resource Management Studies, New Zealand.

Photo by Kym Rohman

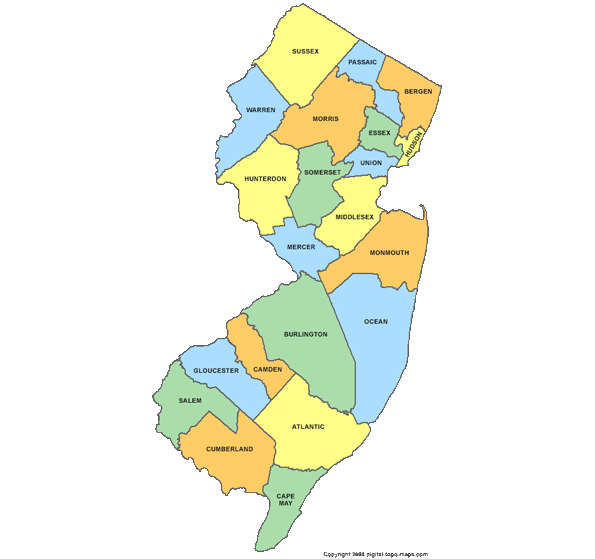

Map courtesy of Passaic Public Library

Map courtesy of Passaic Public Library