Why do I persist in riding Amtrak, the short name for the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, a company originally owned by the freight railways, but now subsidized by Congress and run like a Russian bureaucracy, complete with late trains, sullen employees, myriad petty regulations, budget deficits, cold coffee, feather bedding, broken seats, clogged toilets, rail cars that feel like buses, and a schedule that serves the interests of congressmen, lobbyists, unions, budget stimulators, and small-town mayors, but rarely passengers?

Isn’t it time to let Amtrak go the way of such failed railroads as the Nickel Plate, Erie Lackawanna, Chicago & Alton, Rock Island, Maine Central, Wabash, Missouri Pacific, or the New York Central, lines that outlived their corporate incarnations and were either wound up or merged into larger entities?

Amtrak was set up in 1971 to replace the passenger rail network that was killed off by government regulations, the Interstate Commerce Commission, subsidized air and road travel, and urban blight. The new entity went to work hauling passengers on a route system better adapted to 1921 than 1971. The earlier trains were faster.

It’s hard to imagine Leland Stanford or E.H. Harriman buying into the Amtrak business model. Forty years after Amtrak’s creation, little of its plan has changed. It offers corridor services on the East and West coasts and, in between, a meandering schedule of trains that account for less than one percent of all intercity travel.

Buyers could easily be found for the Northeast Corridor service between Boston and Washington. Better yet, allow competition on the line, and auction off the franchise rights, using the proceeds to pay down national debt.

England had the dreadful network that operated as BritRail. After it was privatized, Britain’s rail service became competitive, passenger friendly, faster, and more comfortable.

Compare the new British private train system with the Amtrak experience (“Enjoy the journey”). Think about New York’s Pennsylvania Station, a subterranean strip mall with dank corners, uncomfortable chairs in cheerless waiting rooms, confusing destination boards and dreary platforms that have seen few improvements since I first used them in the early 1960s.

Passengers buying Amtrak tickets in Penn Station stand in a line that feels like Ceauşescu’s Romania. Only one or two agents are on duty, the tickets are expensive, you need you an identity card to buy one, and getting on the train has the feel of descending into a Chilean mine.

At the cost of billions, there’s a plan for a new “Moynihan Station” across the street, although much of what’s wrong with Penn Station could be fixed if Amtrak outsourced the operation to Hyatt.

Its shoddy service explains the rise of discount bus lines that are now digging into core Amtrak passenger revenue between Boston, New York, and Washington. Companies such as Bolt Bus charge $15 or $20 to get from New York to Boston, while Amtrak costs $67 to $95, depending on the day and time.

Bolt leaves from West 34th Street, and departures are punctually on the hour. The seats are cramped, but the buses are clean and have Wi-Fi. The trip takes less time than many trains, when you add in inevitable Amtrak delays. Nor is there a surly Amtrak conductor reading the riot act at each station.

To get a flavor of Amtrak’s attitude toward its passengers, read the cheerful words of its CEO in the on-board magazine: “Our identification policy, random screenings in stations, random on-board ticket verification process and more interactive police efforts—including our K-9 teams—are some of the visible activities we have been working on.” Trains used to advertise comfortable berths with sleeping kittens.

Killing off Amtrak would mean the end of long-haul passenger service, the sleepers that are the heirs to trains like the Twentieth Century Limited. I would deeply regret the absence of long-distance train travel in the United States. But, were Amtrak spun off, its overpriced and indifferent service might be replaced by a network of private operators that would compete to take Americans around a glorious country that longs to be seen by rail.

Even today, Amtrak trains run near full capacity, and the potential to tap into a travel-happy country of 300 million ought to interest a few hedge funds and stock jobbers, not to mention flourishing overseas rail companies.

Already there are nascent private companies and sleeping car owners that offer rail trips to national parks, art museums, jazz festivals, baseball games, and the homes of famous writers. Deregulate the passenger industry, and companies like these will flourish. Railroads are in America’s entrepreneurial DNA.

Recently, for $325, less than the cost of a cramped night in an Amtrak “Slumberette” (emphasis on the “ette”), I rode round-trip in a private rail car, New York Central 3, owned by Lovett Smith III, from New York to Pittsburgh.

Along the way, I sat on the open, rear platform from which presidential candidates whistle-stopped across America, and took in the sweep of the Philadelphia skyline, the majesty of Amish country (I loved the teams of horses pulling plows), the arched bridge across the Susquehanna, the engineering marvel that is the Horseshoe Curve, the path of the Johnstown Flood, and the remnants of the steel industry around Greensburg. Inside the car, I chatted with my fellow passengers, ate elegant meals, and sampled Italian wines (a group on board had organized a tasting). Were Amtrak a service company, not a protection racket set up to bleed government money into padded contracts, it would have the imagination to operate similar excursions.

Instead, Amtrak wants to position itself as the paymaster for a national rail plan. The Department of Transportation recently issued a strategic plan called Moving Forward: A Progress Report. (If Amtrak were to issue a report to its passengers, it could be entitled, “Sorry for the Inconvenience: Due to a Track Incident, We’re Being Held in Baltimore.”)

Amtrak imagines itself as the federal agency that should be hired to spend $117 billion, over thirty years, to build a segregated high-speed rail system between Boston and Washington, and for additional billions, to operate Core Express Corridors between cities less than 500 miles apart.

Such visions of grandeur come from a company that needs nine hours and fifteen minutes to run a train the 444 miles from New York to Pittsburgh; that’s an average speed of 48 m.p.h.

To be fair, not all of Amtrak’s failings are its fault. Most of the tracks on which it operates are owned by freight companies that find passengers a nuisance, and think nothing of shunting aside “the varnish” to send through more coal and containers.

Amtrak, however, is responsible for a corporate culture that makes a mockery of “customer service.” In many ways, it is the perfect metaphor for everything that is wrong with letting Washington have a heavy hand in the economy, or for imagining that an economic revival can be built around companies with federal guarantees.

Amtrak lacks direction, lives off subsidies and stimulating money, and now wants $117 billion to operate high-speed rail that, for the cost differential, would be only marginally better than the private bus companies now competing up and down the East Coast, with fares of one third or less than what Amtrak charges.

Americans would happily pay for low-speed rail, if the food was good, the seats spacious, the broadband fast, and if, on the rails, they could surf, shop, eat tacos, and watch movies.

At the moment, I am riding an Amtrak train that is four hours behind schedule on its way into North Carolina. So far, to use a phrase from railroading legend, the services have not been worth a “plated nickel.”

Photo By Kyle Gradinger, Amtrak Keystone Snowstorm I. Amtrak AEM-7 locomotive 904 leads a Keystone Corridor train through the snow in Rebel Hill, King of Prussia, PA.

Matthew Stevenson is the author of Remembering the Twentieth Century Limited, winner of Foreword’s bronze award for best travel essays at this year’s BEA. Growing up, he was a “Central” man, but loved the majesty of the old Pennsylvania Station. Together with his father, now 91, he recently has waded through a 1969 edition of the ‘Official Guide to the Railways’. He lives in Switzerland.

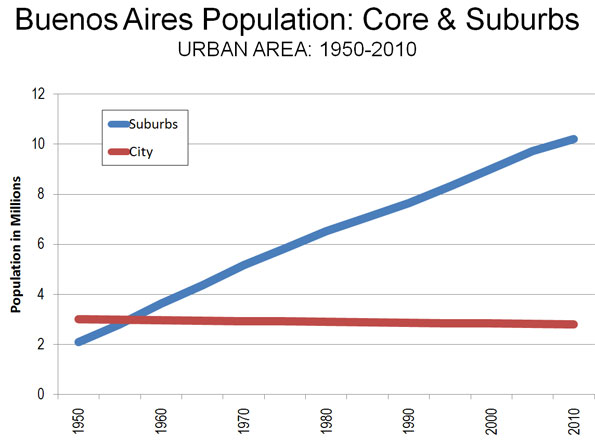

Population and Distribution: According to the last census (2001), the city of Buenos Aires had fewer people than in 1947,

Population and Distribution: According to the last census (2001), the city of Buenos Aires had fewer people than in 1947,

The suburban poverty is far more pervasive to the southwest and the southeast. Many neighborhoods look similar to modest suburbs in Mexico City, though without the pervasive informal settlements. More people live in informal settlements in the suburbs than in the city, with estimates putting the number at above 500,000.

The suburban poverty is far more pervasive to the southwest and the southeast. Many neighborhoods look similar to modest suburbs in Mexico City, though without the pervasive informal settlements. More people live in informal settlements in the suburbs than in the city, with estimates putting the number at above 500,000.