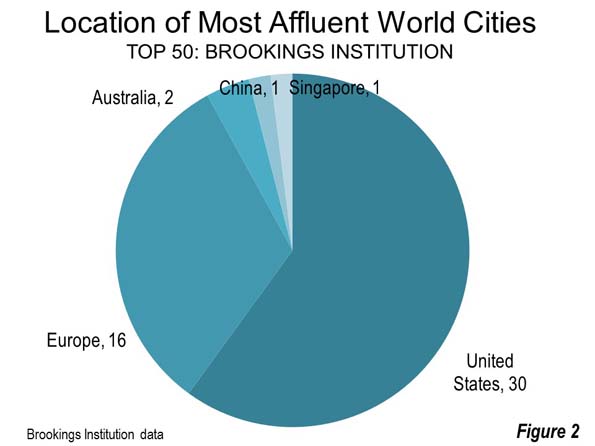

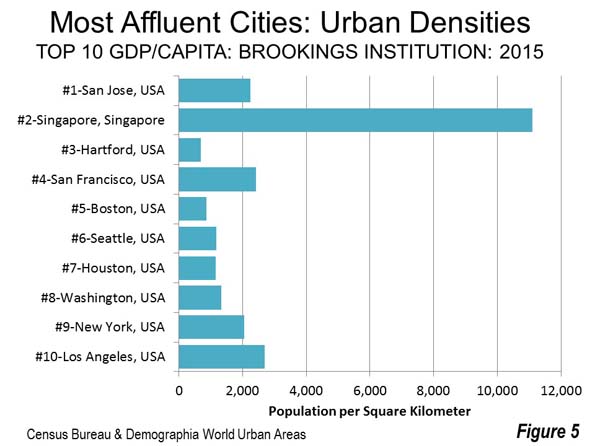

Houston is a city (metropolitan area) of superlatives. The most recent Brookings Institution data shows that Houston has the seventh strongest per capita economy (gross domestic product) in the world (Figure 1). This places Houston above New York and more surprisingly, perhaps, other cities perceived to have strong economies are far below Houston and outside of the top 10, such as London, Tokyo and Chicago.

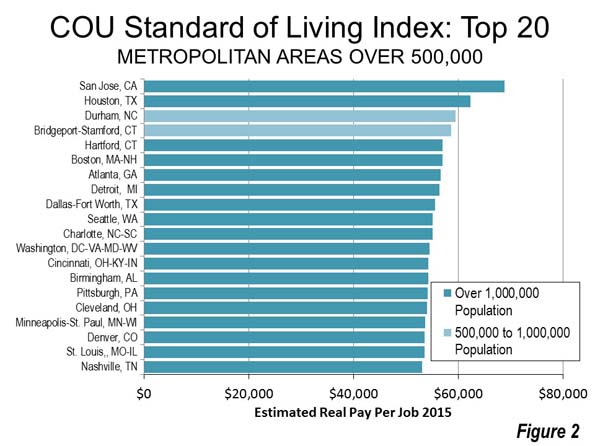

The recently released COU Standard of Living Index also ranked Houston just behind San Jose in real pay per job for households entering the housing market (Figure 2).

Distribution of Population Growth

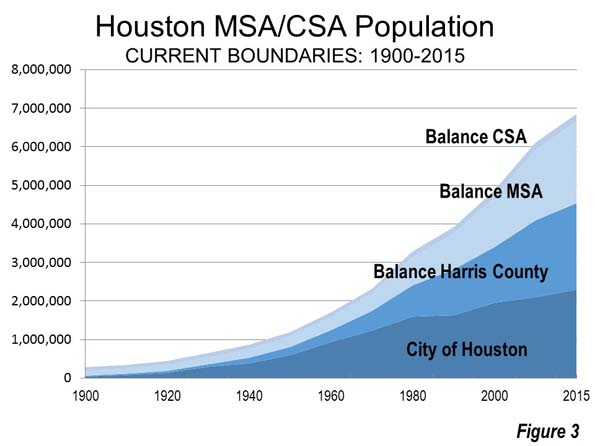

Houston is among the newer of the world’s great cities. It has experienced sustained growth in every decade since the turn of the 20th century. The area constituting its metropolitan region (combined statistical area) has grown at more than 1.5 percent in each decade since 1900. In the 1920s and the 1980s, Houston grow at a rate of more than 3.5 percent annually at has grown an average of 2.2 to 2.3 percent annually since 2000. It took until 1950 for Houston to reach 1 million residents. By 1980, the population was 3.3 million and by 2015 had doubled to 6.8 million.

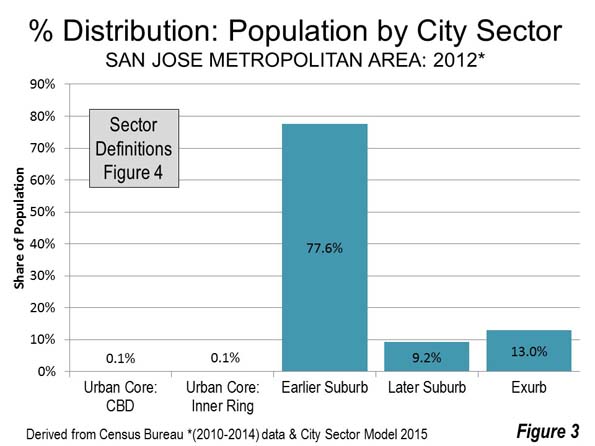

As is typical for a growing city, the strongest early growth was in the core municipality (Houston) and then gradually shifted to the nearby suburbs and outer suburbs (Figure 3)

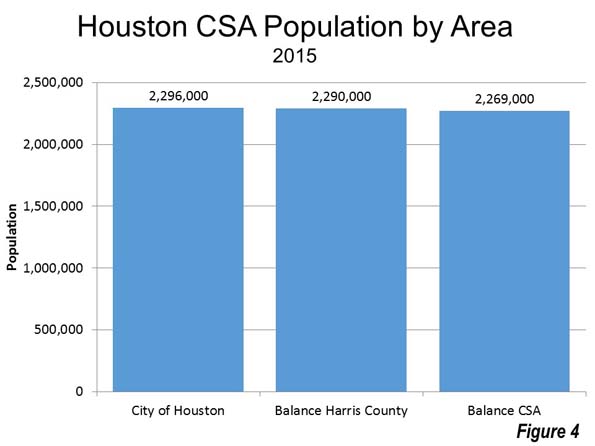

At this point, near parity has been reached. The municipality of Houston, the suburbs within the core Harris County (the county also home to most of the city) and the outer suburbs, beyond Harris County have nearly equal populations, at approximately 2.3 million each (Figure 4).

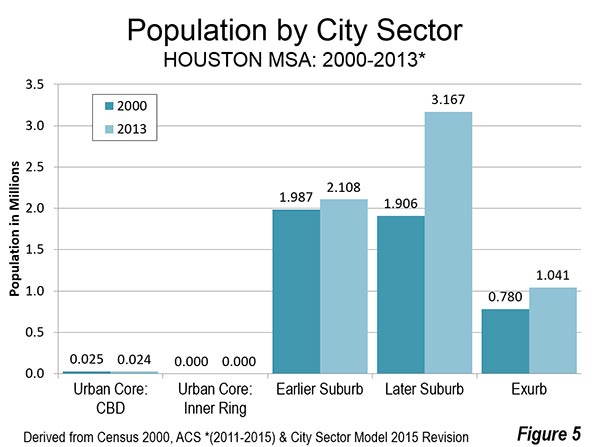

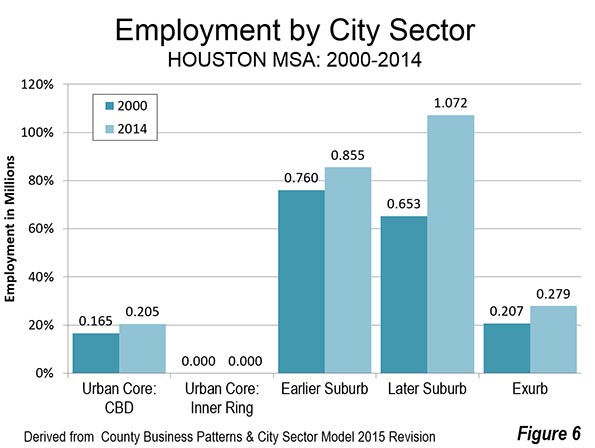

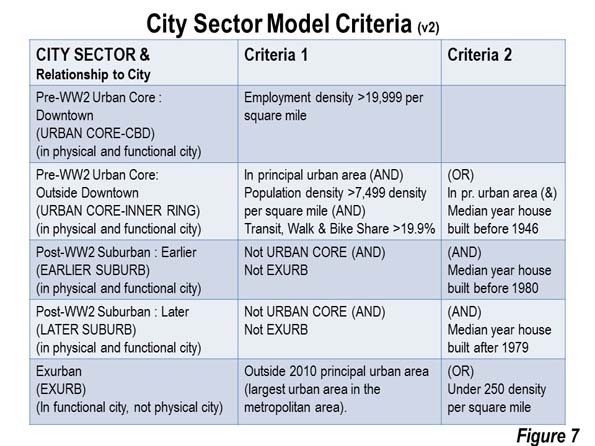

Like other cities that have experienced most of their growth since World War II, most of Houston is suburban. Between 2000 and 2013, the greatest growth was in the Later Suburbs and Exurbs. There was also growth in the Earlier Suburbs (Figures 5 and 7).

Large Centers and Decentralization

There was a similar pattern of growth in employment. The greatest growth was in the Later Suburbs and there was also strong growth in the Exurbs and the Earlier Suburbs (Figures 6 and 7). The central business district (downtown) ranks eighth in total employment in the nation and also experienced growth. The Texas Medical Center is the largest life sciences center in the world. The center is located south downtown and rivals some of the nation’s largest central business districts, larger than Minneapolis and nearly as large as Denver ,, with more than 100,000 employees (see photograph above). There are other large centers, such as the Port of Houston, the Galleria (Uptown) and the Energy Corridor. Houston is one of the best examples of a decentralized city, with major employment centers throughout.

Higher than Average Urban Density

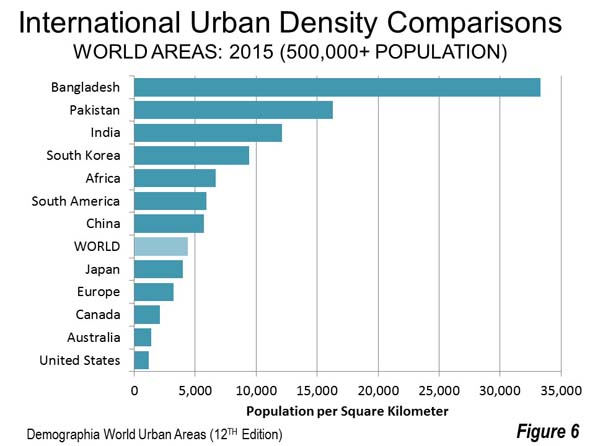

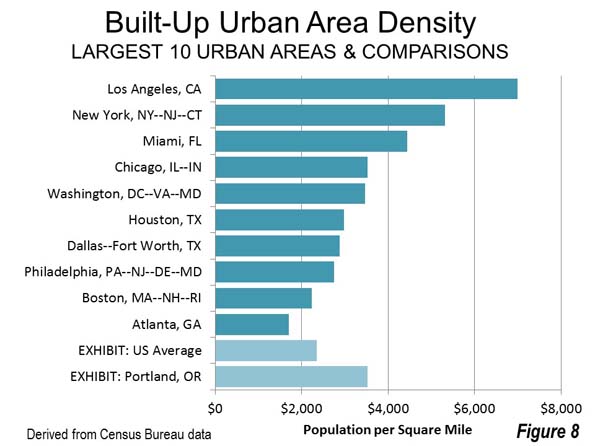

Houston is often characterized as a “sprawling” urban area. In fact, however, Houston has a higher than average urban density for the United States (by eight percent) and an urban density approximately 75 percent higher than Atlanta and Charlotte and denser than Philadelphia and Boston. Even Portland, with its carefully cultivated international reputation for high density is only 18 percent denser than Houston (Figure 8). Of course, all US urban areas are less dense by international standards than their foreign counterparts.

Attracting the Most New Residents

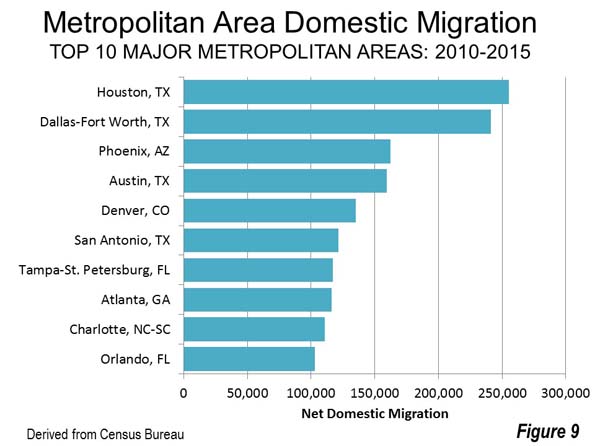

Since 2010Houston has led the 53 metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 population in net domestic migration. In that time Houston has attracted 255,000 new residents from elsewhere in the nation, followed closely by in-state rival Dallas-Fort Worth (241,000). The four largest Texas metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 population were among the six attracting the largest net domestic migration, with fourth ranked Austin attracting 159,000 and sixth ranked San Antonio adding 122,000. Only third ranked Phoenix and fifth ranked Denver were from outside Texas. Eight of the top ten were from the South (Figure 9).

There are at least two important keys to Houston’s attractiveness. Obviously, its strong job-creating economy has opened career opportunities for people from other parts of the country. In addition, Houston’s favorable housing affordability has been an important factor. Seminal recent academic research has pointed to the importance of housing affordability in attracting domestic migrants (such as Ganong and Shoag).

Enviable Improvement in Relative Traffic Congestion

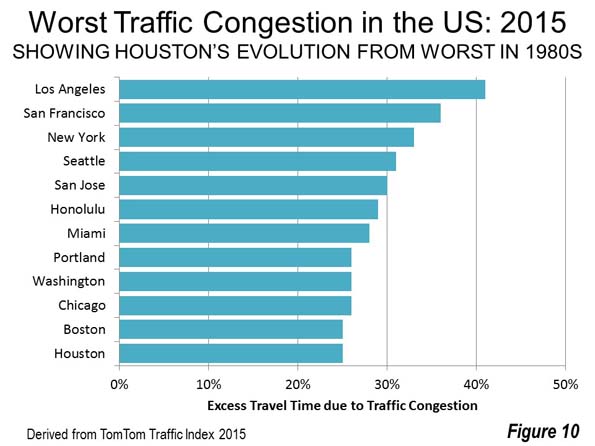

Houston has been more successful in controlling traffic congestion than many other cities. In 2015, Houston tied with Boston for the 11th worst traffic congestion in the United States, according to the TomTom Traffic Index (Figure 10). This is a far better rating than in the middle 1980s, when the Texas Transportation Institute ranked Houston as having the worst traffic congestion in the nation.

Since that time, Houston has managed to have spectacular population growth, yet has kept up with it by expanding its freeway and arterial systems, along with traffic management improvements. Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, San Jose, New York, Honolulu, Miami, Portland, Washington and Chicago have seen their traffic congestion become worse than in Houston over the same period. Houston is larger in population than all but three of these nine metropolitan areas (New York, Los Angeles and Chicago), more than twice the size of San Jose and Portland and nearly seven times that of Honolulu. Further, exhibiting the association between greater traffic congestion and higher population density, all cities ranked worse than Houston have higher urban densities.

World’s Energy Capital Poised for Employment Growth

Houston is widely acclaimed as the energy capital of the world. Urbanscale.com says that “The only other U.S. city that rivals Houston’s domination of a single industry is New York’s preeminence in the financial sector.” Of course, Houston’s energy industry has faced considerable challenges over the past couple of years as Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) have driven the price of oil down by producing more oil. However, the “good times” could return soon for Houston, as there are indications that OPEC will reduce its production. Further, and perhaps even more importantly, Houston could benefit from the new Trump administration’s commitment to a more consumer oriented energy policy, appearing likely to generate substantial employment and growth in the newly unleashed sectors.

Photo: Texas Medical Center (by author)

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.