With much fanfare, the Banking Committee of the United States Senate approved the Livable Communities Act (S. 1619, introduced by Democratic Senator Dodd of Connecticut). A purpose of the act is expressed as:

…to make the combined costs of housing and transportation more affordable to families.

The Livable Communities Act would provide financial incentives for metropolitan areas to adopt “livability” policies, which are otherwise known as “smart growth,” “growth management” or “compact city” polices.

“Livability” is the latest rallying cry for planners who want to draw lines around urban areas and force people out of their cars and into denser housing. Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood has defined livability as “if you don’t want an automobile, you don’t have to have one.” This meaningless slogan presumes that people are forced to have cars. If you are rich enough, you can live without a car on the Upper East Side of Manhattan or Chicago’s Gold Coast. If you are poor enough, you cannot afford a car, which means fewer job prospects and higher retail prices from merchants serving a captive market.

Perhaps someday we will be beamed from place to place as in Star Trek. However, in the interim, a serious alternative to the car – hopefully a far cleaner, more efficient version – does not loom on the horizon. For all but a privileged few, cars and the quality of life and cars will remain “joined at the hip”. This is why research shows a strong correlation between the automobile access in an urban area and economic growth.

The Report Card

It is not premature to issue a report card on the Livable Communities Act, since the effect of its favored policy prescriptions are already well known. Metropolitan areas more inclined toward the act’s menu of livability policies (such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland, Washington and others) are compared to other metropolitan areas (such as Dallas-Fort Worth, Atlanta, Indianapolis, Kansas City and others). Our analysis shows that, for most people, livability policies produce less livability, in terms of higher costs and a lesser quality of life, especially in greater traffic congestion, longer travel times and more exposure to air pollution (Note 1). They will therefore be referred to as “so-called” livability policies.

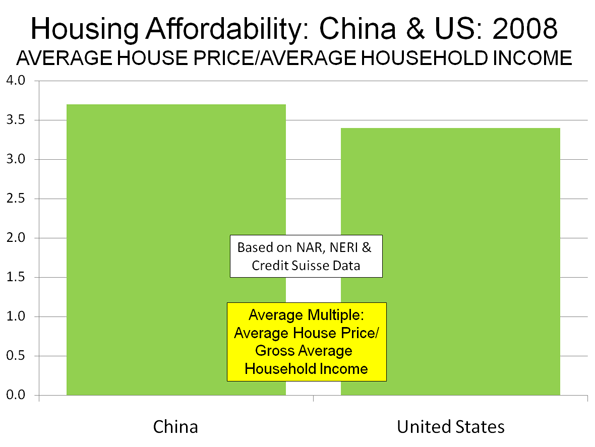

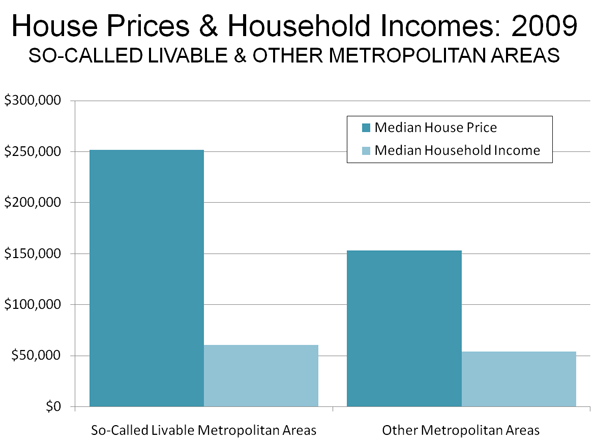

Housing Affordability: The Livable Communities Act seeks to make housing more affordable. Sadly, the record associated with such policies in terms of affordability is nothing short of dismal.

The Livable Communities Act receives an “F” for home ownership affordability

House prices are considerably higher in the metropolitan areas more inclined toward so-called livability policies. The so-called livable metropolitan areas have nearly 50% higher house prices, after adjustment for incomes (Figure 1). If house prices were at the same level relative to incomes as in the other metropolitan areas, the median price would be $80,000 less. This would mean about $5,000 less in annual mortgage payments. In the least affordable so-called livable metropolitan areas, fewer than 40% of households can afford the median priced house (Los Angeles, New York and San Jose). In all the other metropolitan areas, more than 70% of households can afford the median priced house (Note 2). It takes a lot of gasoline to equal that difference.

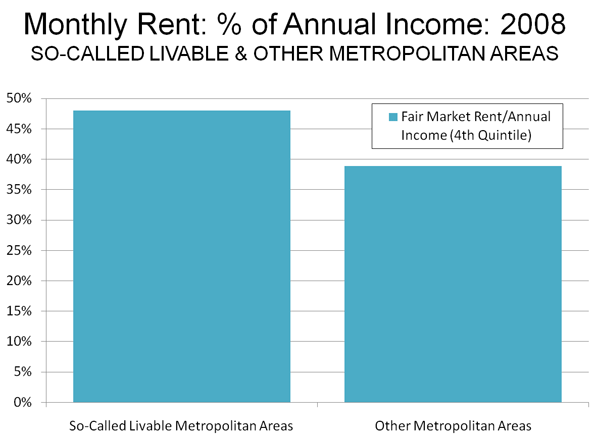

The Livable Communities Act receives an “F” for rental affordability.

Rents are also higher in the so-called livable metropolitan areas (Figure 2). The US Department of Housing and Urban Development “fair market rents,” (estimated at the 40th percentile of the rental market, including utilities) for a two bedroom apartment was 25% higher in the so-called livable metropolitan areas in relation to the fourth household income quintile (top of the bottom 25%).

Why Housing is More Expensive in Livable Metropolitan Areas: The land use regulations typical of the so-called livable metropolitan areas force house prices up by prohibiting development on most available land (urban growth boundaries), imposing building moratoria or, in some cases, by requiring excessively large suburban lot sizes, making it impossible to build housing that is affordable to middle income households. All things being equal, prices increase where supply is restricted, as indicated by a broad economic literature.

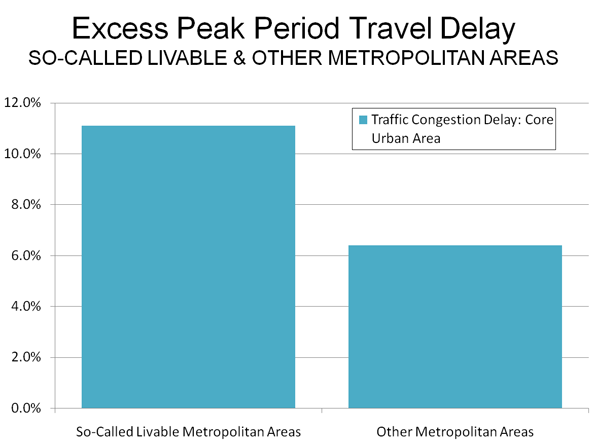

Transportation

According to the findings in the Livable Communities Act the nation wastes 4.2 billion hours in traffic congestion and loses $87 billion annually from the costs of congestion. The congestion cost is principally the cost of time.

Transportation Costs: Since commuting by transit nearly always takes longer than commuting by car (twice as long in 2007), any switch to transit is likely to increase costs (lost time is lost time, whether in a train or in a car). The balance of congestion costs are in excess fuel consumption, which would likely also increase under the so-called livability policies, because higher densities produce greater traffic intensities (this from Sierra Club based research), which means more congestion and slower travel speeds, which reduces fuel economy.

The Livable Communities Act receives an “F” for transportation affordability

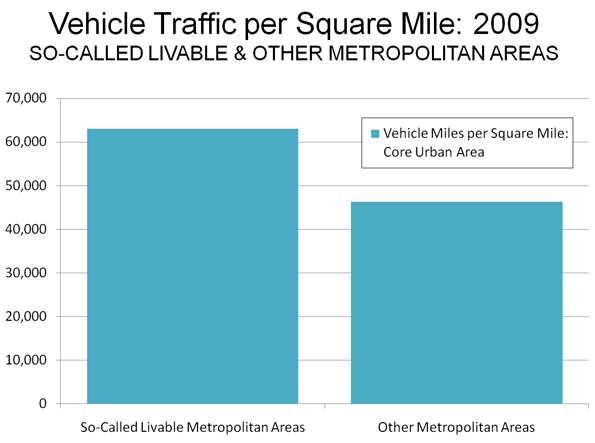

Transportation Quality of Life: So-called livability policies worsen traffic congestion and air pollution. This is indicated by the latest INRIX traffic scorecard showing that average travel delays during peak travel periods are nearly 75% greater in the so-called livable metropolitan areas (Figure 3). Federal Highway Administration data indicates that the intensity of traffic is more than one-third higher in the so-called livable metropolitan areas (Figure 4)

The greater traffic intensity also has negative health impacts. The American Heart Association noted that being close to congested roadways increases the likelihood of heart attack and stroke. The American Heart Association cites a study indicating that “a person’s exposure to toxic components of air pollution may vary as much within one city as across different cities.” Obviously, such exposure will be greater where traffic densities are higher.

The Livable Communities Act receives an “F” on transportation related quality of life issues.

Consumer Preferences

In its findings, the Livable Communities Act says that the demand of new housing in dense, walkable (so-called “livable”) areas is 15 times the supply. This misses the extensive overbuilding of dense, walkable communities that ended in the huge condominium bust in Portland, Seattle, Los Angeles, Miami, Atlanta, Chicago and elsewhere. The supply of such housing exceeds the demand, particularly at the current price points.

Consumer preferences are not revealed by planners’ delusions from surveys people answer in the abstract. For example, most people want shorter commutes, but they vastly prefer single family houses to apartments. In the real context of issues like costs, living space, or schools, people express their priorities.

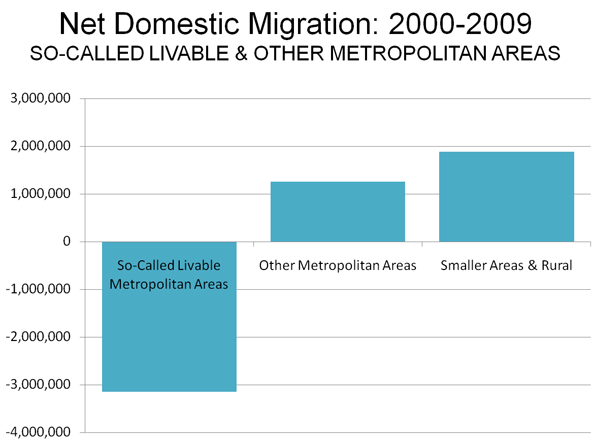

The “litmus” test of so-called livability is what people do, not what they say they might do. Households continue to vote with their cars and are moving away from so-called “livable” areas. According to 2009 domestic migration data compiled by the Bureau of the Census:

- The so-called livable metropolitan areas lost more than a net 3,140,000 residents to other areas of the nation, while other metropolitan areas gained more than 1,000,000 and smaller areas gained nearly 2,000,000 (Figure 5).

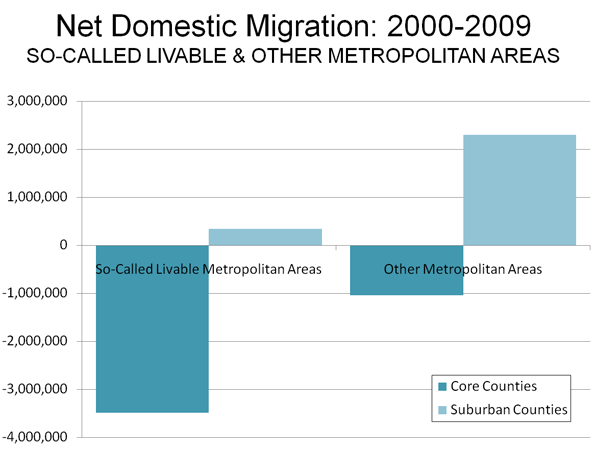

- Nearly 3,500,000 residents left the core counties of the so-called livable metropolitan areas for other parts of the nation, while the suburbs gained 340,000 residents.

- In the other metropolitan areas, more than 1,000,000 residents left the denser core counties, while the suburbs gained 2,300,000 (Figure 6).

The Livable Communities Act receives an “F” for consistency with consumer preferences

The Report Card: Not Livable at All

The Livable Communities Act report card is shown below. In other words, if enacted, it is likely to produce a failing grade for families even if it wins straights A’s with planners, academics and inner city developers.

|

Report Card Livable Communities Act |

|

|

Subject |

Grade |

|

Home Ownership Affordability |

F |

|

Rental Affordability |

F |

|

Transportation Affordability |

F |

|

Transportation Quality of Life |

F |

|

Consistency with Consumer Preferences |

F |

|

Overall Grade |

F |

|

Additional Comments: The favored policies would reduce mobility to major parts of the metropolitan area, which would reduce access to potential employment opportunities and retail establishments with lower prices. |

|

Note 1: The analysis covers metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 population. The “so-called” livable metropolitan areas are classified as those with “more restrictive” land use regulation by Demographia. The other metropolitan areas have less restrictive land use regulation. See note 7 of http://www.demographia.com/db-overhang.pdf.

Note 2: Calculated from the National Association of Homebuilders-Wells Fargo Housing Opportunity Index.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

Photo: Overbuilding Dense Walkability in Miami (photograph by author)

In fact, much has changed. Religion in America is alive and well, but it’s different. Although Christian churches continue to dominate the religious landscape in the United States, there are new religious neighbors. Cultures and religious traditions that once existed “somewhere over there”, have moved beyond the large cities of the U.S. into the suburbs and exurbs, places where evangelical mega-churches have flourished for decades.

In fact, much has changed. Religion in America is alive and well, but it’s different. Although Christian churches continue to dominate the religious landscape in the United States, there are new religious neighbors. Cultures and religious traditions that once existed “somewhere over there”, have moved beyond the large cities of the U.S. into the suburbs and exurbs, places where evangelical mega-churches have flourished for decades.