This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism titled “The Texas Way of Urbanism“. Download the entire report here.

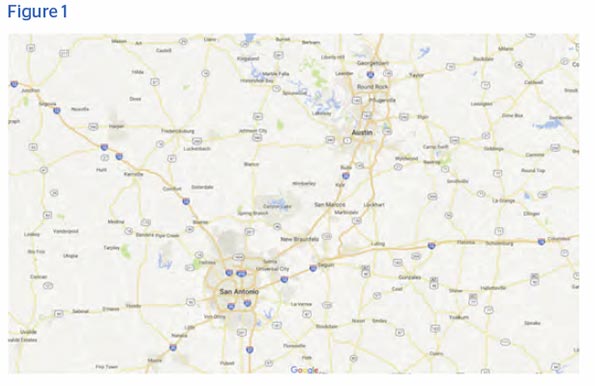

A new economic corridor is emerging in the center of Texas. Hays and Comal Counties are part of the Austin and San Antonio metropolitan areas respectively. But they are not merely suburbs capturing overflow from larger cities. They are becoming part and parcel of an emerging 80-mile long economic corridor between San Antonio and Austin, along the I-35. In the process, this region centered around San Marcos and Hays County, is emerging as a hub in its own right.

This new corridor is beginning to resemble another Texas style “metroplex” between Dallas and Ft. Worth. It is a development that can also be compared, in some aspects, to other growth corridors, such as the San Jose to San Francisco strip, the Raleigh-Durham area and the Wasatch Front stretching from Ogden through Salt Lake City to Provo.

Texas State Demographer Lloyd Potter foresees an additional 1.5 million people in the corridor by 2030, a nearly 34 percent jump. In Hays and Comal counties, the state projects between 69 and 44 percent in population growth during that period. “Over the next 50 years, Austin and San Antonio will become a single mega-metro area,” Austin Mayor Steve Adler says. “The corridor in between will be the first reflection of this coming future, providing greater connectivity to serve the increasing interdependence and joint economic potential as the two cities grow together.”

As occurs in many emerging regions, the Austin-San Antonio can be considered multi-directional, extending to and from both larger cities, but also from the emerging hub around San Marcos.

The San Marcos segment of the Corridor is already more than a bedroom and retail community. Amazon decided to build an 855,000 square foot fulfillment center in San Marcos (Hays County) that will eventually employ 1,000 people. Sysco Corporation opened a distribution facility in New Braunfels (Comal County) that employs 650 people. More importantly, Texas State University in San Marcos, with nearly 40,000 students and a growing research profile, is anchoring an emerging high tech base for the corridor.

Something big is starting to happen in this once rural region of Texas. This report is divided into three sections that explore – the what, the why, and the future. The best predictor of the future is usually what has happened in the past, let us begin there.

Dimensions of Regional Growth

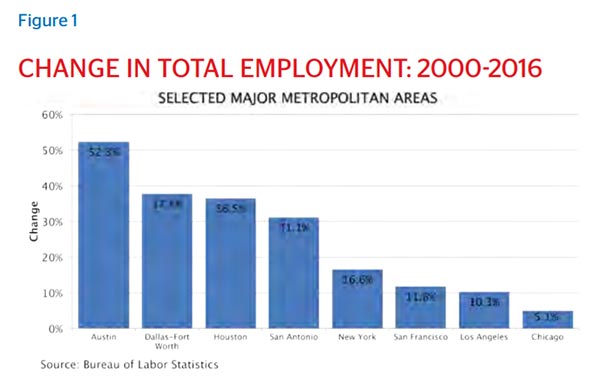

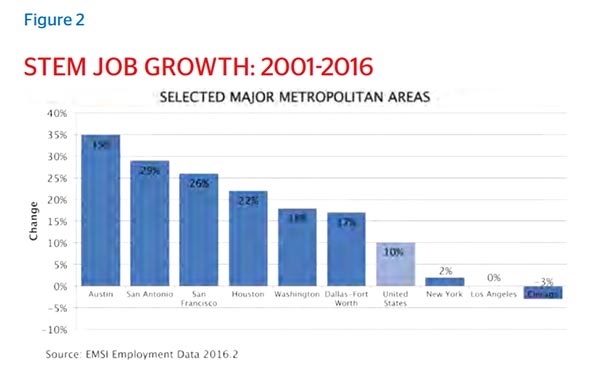

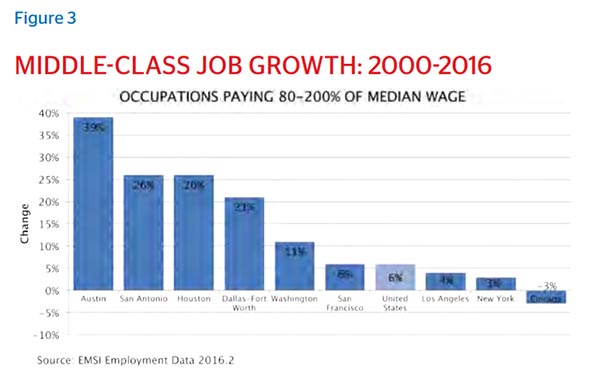

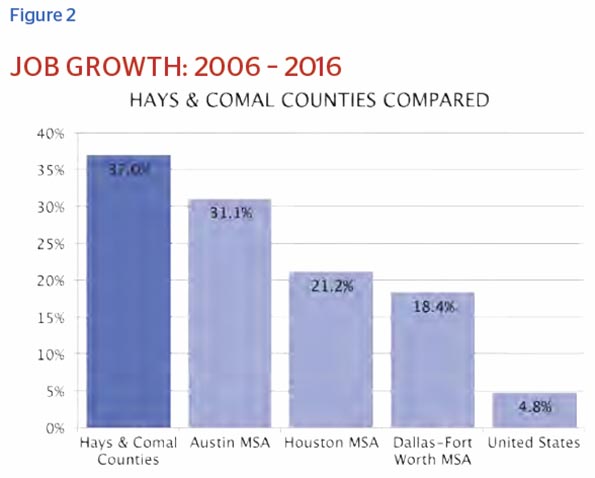

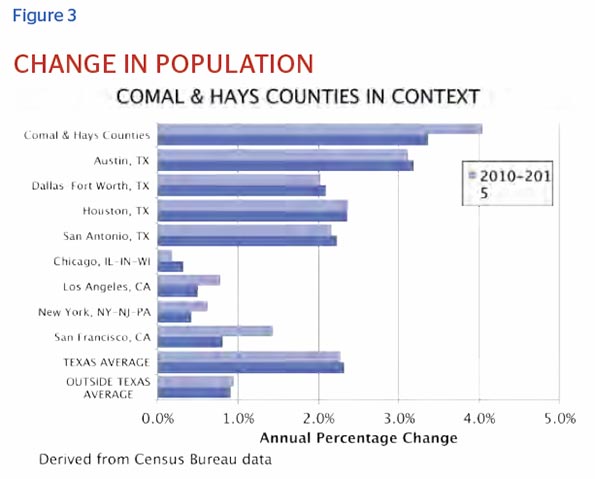

The rate of growth in Hays and Comal Counties is exceptional, even by the standards of Texas. They are far outpacing the nation in both population and jobs, and growing at twice the rate of Texas as a whole. The two counties exceed even the rest of metro Austin, which has historically been among the leaders in job growth nationally. Three of the 25 fastest growing counties in the country are located in the Austin-San Antonio Corridor.

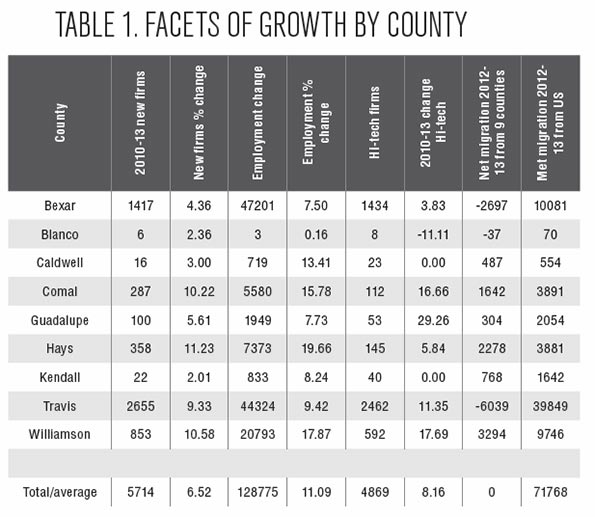

The table below highlights the dimensions of this very rapid growth.

Employment Growth. There has been a pattern of positive employment growth in all counties, with Hays the leader followed by Williamson then Comal. The entire corridor is among the national leaders in job creation, out-distancing not only the nation but Texas as well.

New Firms. We see more new firms in all counties, with the highest percentage growth in new firms occurring in Hays, then Williamson and Comal counties. The definition of new firms used here includes opening of new branches or plants by existing firms that operate multiple establishments.

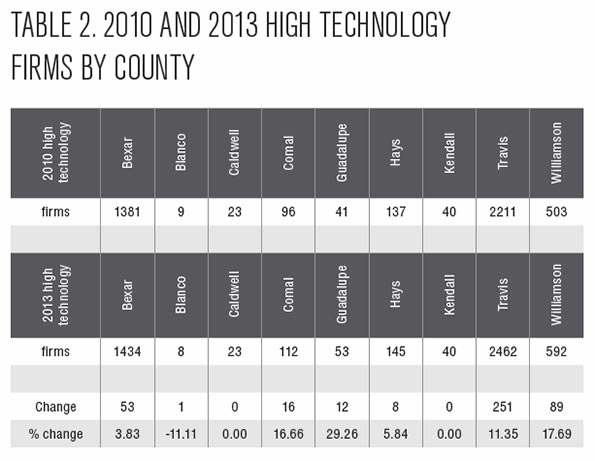

High-Tech Firms. Growth of high-technology firms occurred in 6 of the 9 counties, with Guadalupe the leader in percentage terms followed by Williamson then Comal and Travis counties.

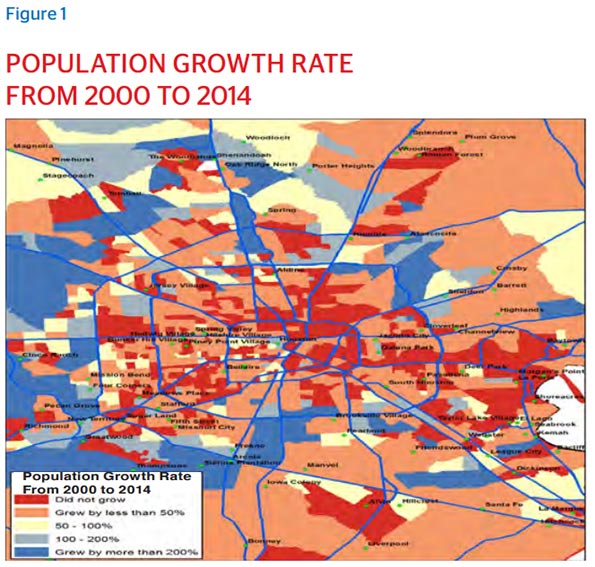

Population. The entire San Antonio-Austin corridor has some of the most rapid growth in the country, as we can see in the first slide. The region also contains many of the fastest growing counties not only in Texas but the country.

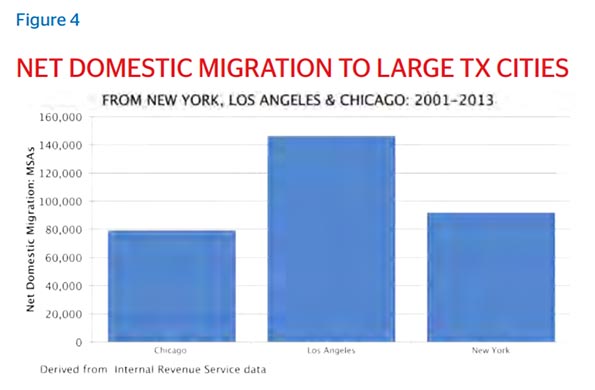

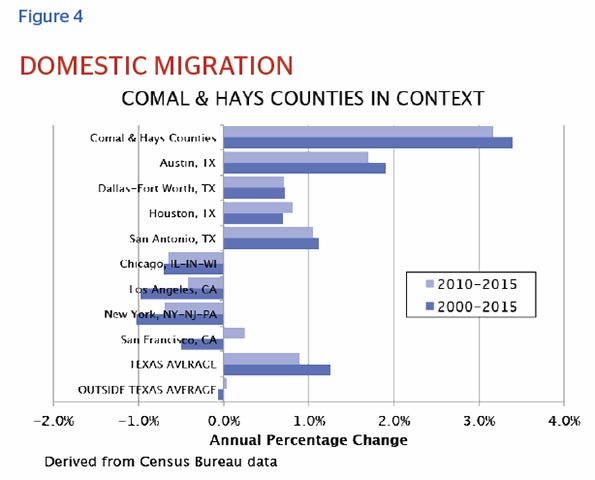

Migration. Williamson County gained the most population from those living in the nine county region, followed by Hayes and Comal. Overall the entire Corridor has experienced large domestic in-migration, well above Texas averages, and even more so in comparison with large metropolitan areas like New York, Los Angeles and Chicago.

The following sections provide more detail on this out-sized performance.

Industries Driving Regional Employment Growth

Employment growth has been broad across several industries, with the fastest growing industry being Electronic Shopping and Mail-Order Houses. Another cluster of fast growing industries are private (not public) firms involved in education and training (Elementary and Secondary Schools, Other Schools and Instruction, Technical and Trade Schools, Business Schools and Computer and Management Training). This does not include the significant role played by Texas State University in education related to business and computer management and engineering.

This job growth, of course, has been driven by population growth. In terms of location quotient, the area remains much stronger in lower-end service industries. For example, Hays and Comal counties have 26 and 16 percent of employment in retail industries compared to only 13 percent nationally.

But this appears to be changing, as evidenced by the growth of key “export” industries — that is goods and services largely consumed elsewhere. This includes key manufacturing fields, such as Industrial Machinery, Motor Vehicle Parts, and Metalworking Machinery. Overall the area is enjoying a manufacturing boom that far exceeds the national average.

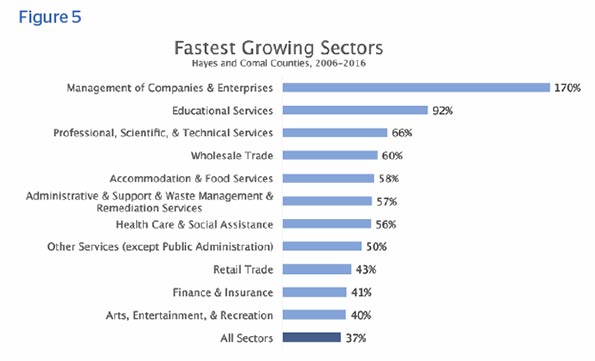

This growth is also evident in several key service industries such as Management Services, Educational Services, and Professional, Scientific and Technical services. Particularly critical has been the logistics and wholesale industry, which serves not just the local economy but the entire regional and nation, with the massive new Amazon facility representative of this type of growth. Although much of the region’s growth has been in traditionally lower-wage service industries, the fastest growing sectors tend to be higher wage, information fields like management of companies and enterprises, educational, professional, scientific and technical services.

Is a High Technology Corridor between Austin and San Antonio Emerging?

Located between the high-tech hub of Austin and the emerging one centered in San Antonio, the region between the two is also showing growth in high-tech firms, as show in table 2 below.

The most rapid growth has been in Basic Chemical Manufacturing, Software Publishers, Computer Systems Design and Related Services, Commercial and Service Industry Machinery Manufacturing, Scientific Research and Development Services, and Pharmaceutical and Medicine Manufacturing.

The high-technology industry with the largest number of establishments was Computer Systems Design and Related Services, consistent with the reputation of Austin as an emerging leader in this area of economic activity. Architectural, Engineering, and Related Services had the second largest number of establishments, followed by Scientific Research and Development Services, Oil and Gas Extraction, and Software Publishers.

The total number of firms in Hays and Comal remains much lower than in the far larger Travis and Bexar Counties, but their growth shows that the San Marcos Corridor segment is already participating in the regional high tech cluster, with potential future upside from its growth.

If the region is to develop into a larger high tech center, Texas State University will play a vital role in powering that transformation as it continues to expand its research reputation and the funding that goes with it. Texas State has already helped launch an important tech industry venture with the establishment of the Science, Technology and Advanced Research (STAR) Park which sits on 58 total acres dedicated by Texas State for future expansion. Executive Director Stephen Frayser describes the park as an accelerator, now helping eitht for-profit companies to market, including three student startups. STAR One, the first building, broke ground with 14,000 square feet, but filled up quickly. Frayser says, “We have had to expand twice since opening in November, 2012 and will have 36,000 square feet operational by September 1, 2016.”

How the future growth of Texas State, its research funding quest, and initiatives such as STAR Park play out will do much to determine the degree to which San Marcos’ high tech ambitions take off.

Population Growth and Migration

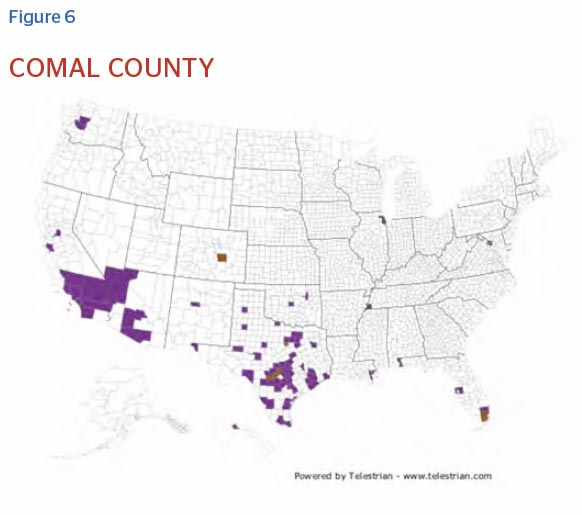

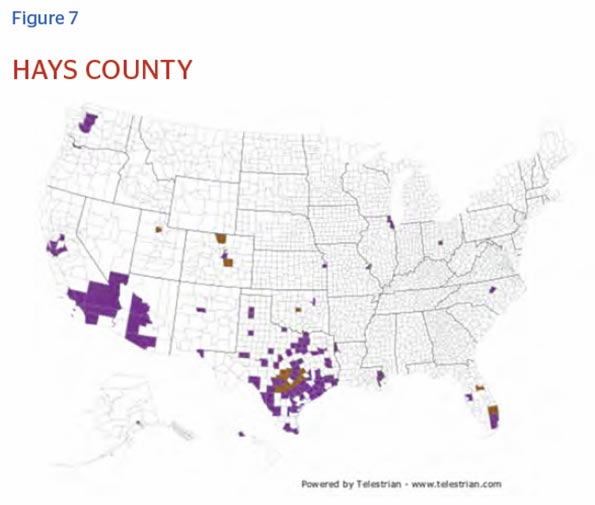

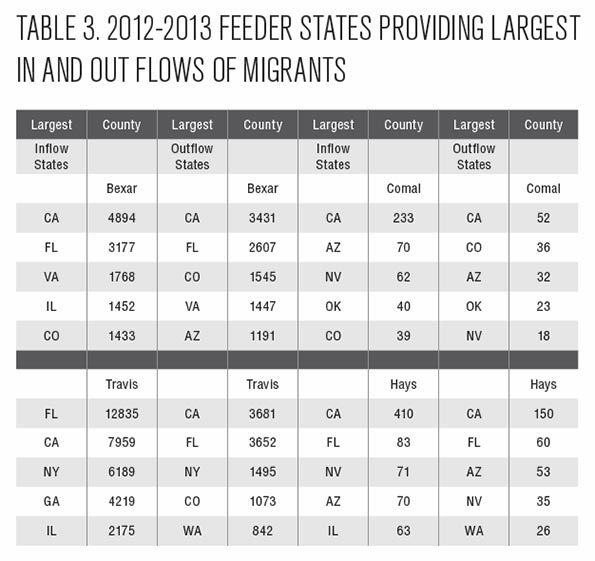

People are an increasingly critical raw material for economic growth in San Marcos (Hays County) and New Braunfels (Comal County). Overall Hays and Comal have enjoyed among the fastest growth rates of any counties over 100,000 in the nation, easily outpacing even the torrid growth experienced by Austin and other Texas cities. The following map tells us the regions and feeder states from which Hays and Comal Counties have been drawing net migration.

Outside Texas, California was the largest source of in-migration and also the largest destination for out-migration. (In the case of Travis County, California is the second largest source of in-migration with Florida being first.) Focusing on California and Florida, we see total net gains from California equal to 6,182. In the case of Florida, we see total net gains equal to (9,776 during the 2012-2013 period.

Explaining Regional Growth: A Geographically Advantaged Region

What accounts for the growth of the San Marcos Corridor? Three factors loom large: the region’s unique geographic advantages and exceptional quality of life that set it apart from other suburban regions, and the high quality public policy environment of Texas.

Just as Dallas-Ft. Worth benefitted from being a highly multi-polar “metroplex” that evolved from two formerly distinct urban areas, a similar (if smaller scale and more nascent) effect is taking place between Austin and San Antonio.

Dallas and Ft. Worth are 33 miles apart. Austin and San Antonio are 80 miles apart. Despite the greater distance, much of the I-35 corridor is already developed between the two. It makes logistical and financial sense to locate some facilities, such as Amazon’s fulfillment center, in the San Marcos Corridor segment to easily serve both markets.

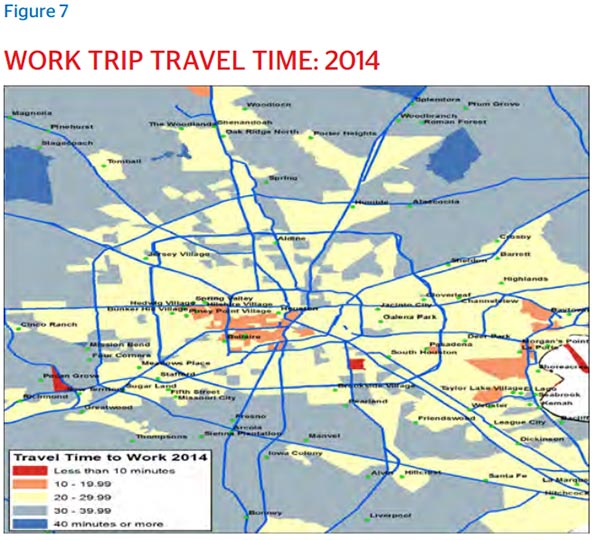

The same effect applies to people too. Those who live in the corridor have the ability to commute to either major city to work, giving them access to more potential employment opportunities. San Marcos is about 30-45 miles from downtown Austin or San Antonio – a long but doable commute – which is shorter than in many suburban areas. However, in both Austin and San Antonio, there are many jobs located in suburban areas that are closer to San Marcos.

A look at job growth by occupational category reveals the Hays and Comal advantage. Nationally, the largest 21 broad occupational categories account for one third of all employment. In Austin and San Antonio, 21 broad occupational categories (not necessarily the same) also account for around one-third of all employment.

Of these 21 categories of jobs, 16 were in common to Austin and San Antonio, and the percentage change in these types of jobs were compared for Austin and San Antonio. Somewhat remarkably, 8 of the 16 job categories show a pattern where either Austin or San Antonio has higher than national employment growth while the other city has lower than national growth.

This may explain the attraction of Hays and Comal counties where residents can commute to work in either metro area. In the face of jobs requiring specific skills disappearing in one city, workers find new jobs appearing in the other city. They simply need to commute to a new job in the other city, rather than being forced to move.

This effect is magnified for households with more than one worker. One spouse can work in Austin, the other in San Antonio. Outside of pricey Austin neighborhoods, inexpensive suburban housing can be found throughout the Corridor.

The Quality of Life Advantage

Perhaps nothing drives growth in the region more than the quality of life offered by the Corridor. When we asked several business leaders what brought people here it wasn’t too long in the conversation before the discussion turned from the tangible reasons to the intangible, the big intangible being quality of life.

Dan Stauffer, Vice President of Marketing/Real Estate of McCoy’s Building Supply (which moved its headquarters from Houston to San Marcos decades ago) was quick to bring up the quality of life draw that Austin and San Antonio has for people who move to the area. Again the geographic advantage of the region is key. Austin and San Antonio are culturally very different cities; residents of the San Marcos Corridor visit both and enjoy all they have to offer – then come home and live in the relative peace and tranquility of Central Texas.

The overpowering quality of life factor in the Corridor is the Texas Hill Country. Bordered west of the Austin/ San Antonio Corridor the Hill Country is immense and very unique. It covers 11,111 square miles, offering plenty of recreational options including tubing opportunities in the Guadalupe River (Comal County), The Blanco (Hays County) and a lot more. Overall the elevation goes from about 510 feet above sea level, just east of San Marcos, to 853 feet in Wimberley to its highest elevation of 2,460 feet further in.

The Hill Country’s attraction ranges from residents and CEOs who want to move their company to be close to their ranch full time, to city dwellers who have second homes they visit to get away from it all. The Wall Street Journal’s recent article describing a “land rush for the rich” in the Hill Country testifies to its red-hot appeal.

Near New Braunfels is the Town of Gruene – which features one of America’s oldest Dance halls – Gruene Dance Hall (established 1878). It attracts over 1.2 million guests per year according to Rusty Brockman, Economic Development Director of the Greater New Braunfels Chamber of Commerce. Many artists – legends such as Chubby Checker, Lyle Lovett, and Willie Nelson and relative newcomers like Kevin Costner have performed there according to the Gruene Dance Hall website.

The Texas Policy Advantage

Although the region has generally outpaced other Texas cities in terms of the growth, the area’s emergence has much in common with the same things that have driven the growth of other Texas cities.

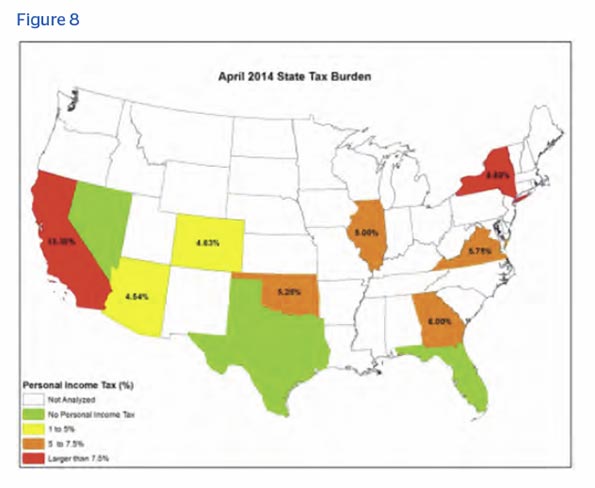

There are a unique set of conditions that exist in both Texas and the emerging Central Texas Corridor which do not exist in very many other places. We’re not saying that they individually don’t exist throughout the other 49 states, but together this complete set of free market oriented set of rules and tax rates would be hard to find in too many places. These include being a no income tax state, a right to work state, and having biannual legislative sessions that limit the opportunity for regulatory mischief.

These reasons provide a base of attraction for businesses and people to consider Texas – and the Austin – San Antonio Corridor – to relocate, expand and grow.

Source: Tax Policy Advantage, 2015

Texas also does not impose a traditional corporate income tax, though it does impose a modified gross receipts tax, commonly known as the Margin Tax. However, in 2014, this rate was only 0.975%.

When doing the math, you can see that individuals and businesses coming from the area’s large feeder states can look forward to keeping more of their own money – a worker or investor from California gets a raise of 13.3% for starters, not to mention much lower property prices. The pretax incomes in some feeder states may be higher, but will in most cases be lower once tax burdens are accounted for.

Overall, Texas’ tax climate is ranked 10th by the Tax Foundation.188 California, the state sending the most people to the area, ranks 48th. Other key feeder states to the region also score lower than Texas, include Colorado (18th), Illinois (23rd), Arizona (24th), Virginia (30th), Oklahoma (33rd), Georgia (39th) and New York (49th).

Beyond low taxes, Texas also has a regulatory system that’s friendly to business and housing development. In part this comes from a state legislature that meets only once every two years. Only four states still do this (the others are Montana, Nevada, and North Dakota). The legislatures of every other state meet annually.

A biannual legislative session does not necessarily guarantee less burdensome regulations, though legislators do have fewer opportunities to regulate. But Texas’ biannual legislature is indicative of its business friendly mindset, which we see clearly in the output. This includes a right to work law, which prohibits employees from being forced to join a labor union.

Even within Texas, the counties at the center of the Corridor maintain distinct advantages. One key advantage can be seen in such things as property taxes, which comprise the bulk of the tax burden in Texas. Hays and Comal counties, and their cities, offer favorable numbers that attract not only feeder states migrants, but feeder Texas cities and county migrants.

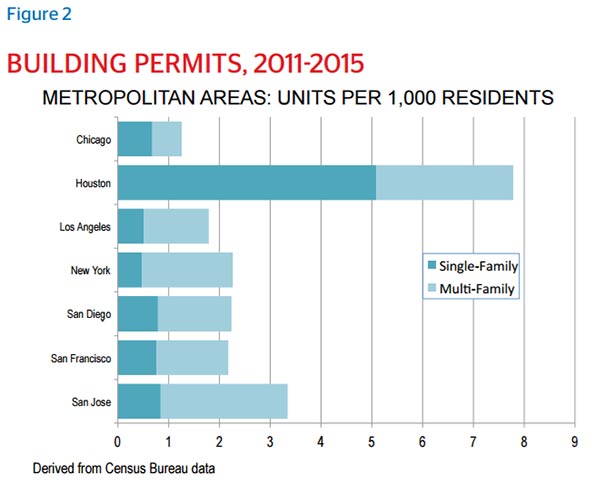

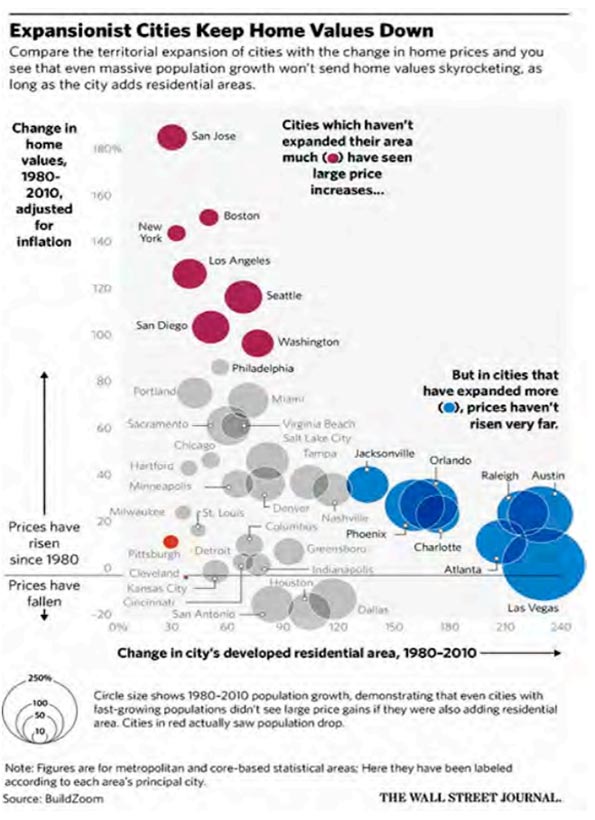

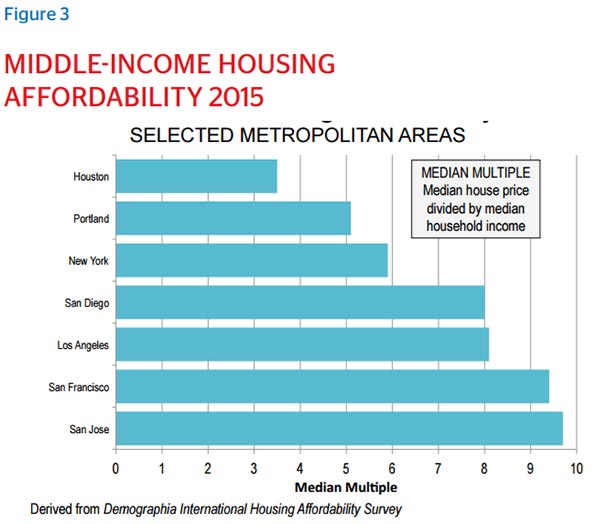

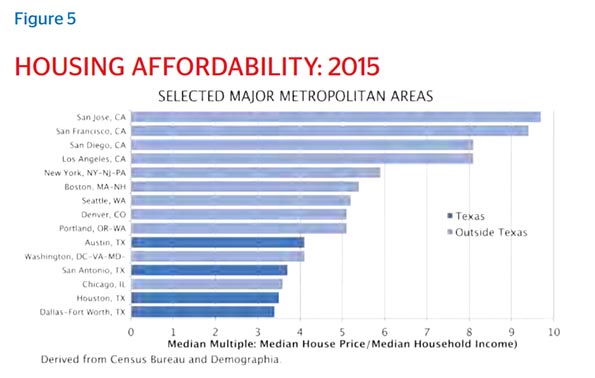

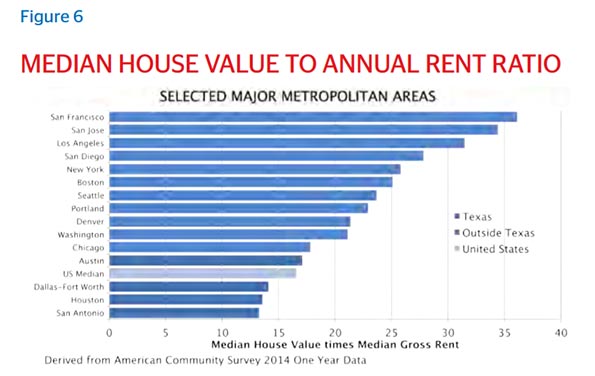

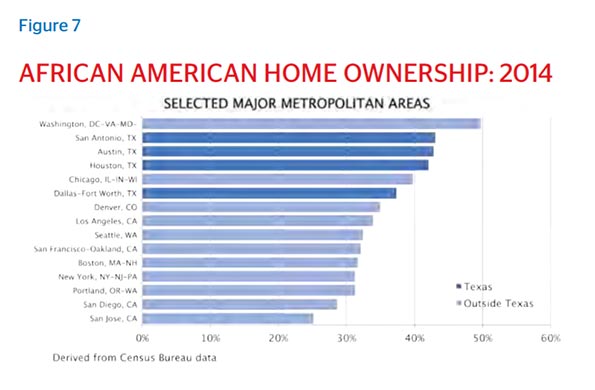

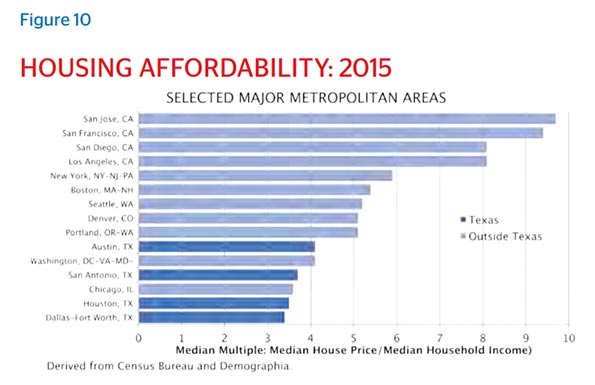

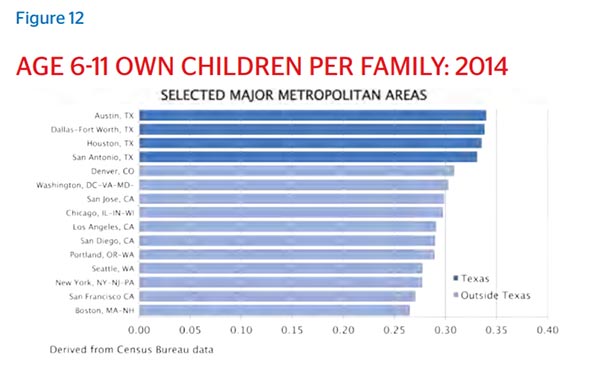

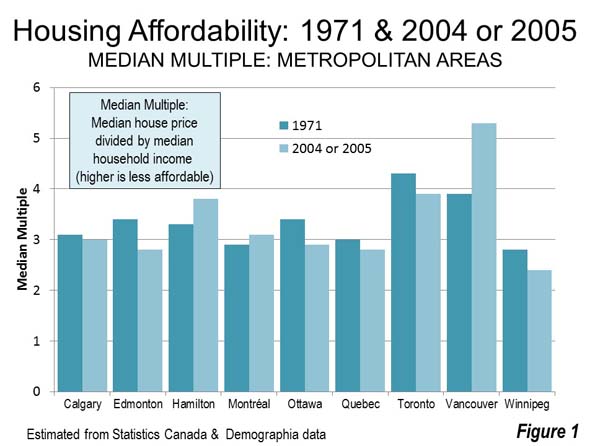

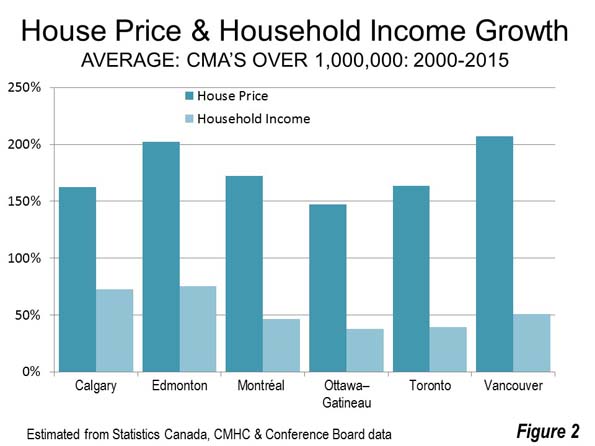

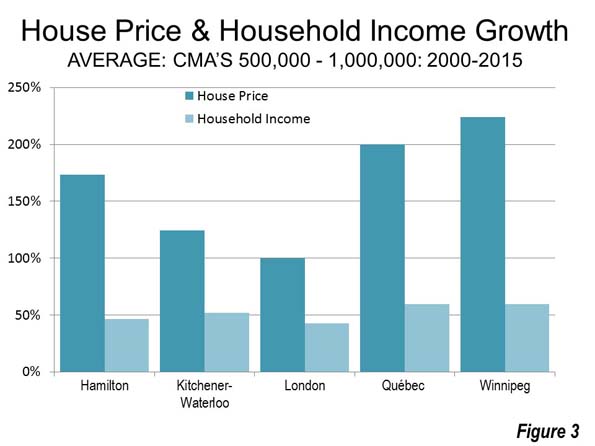

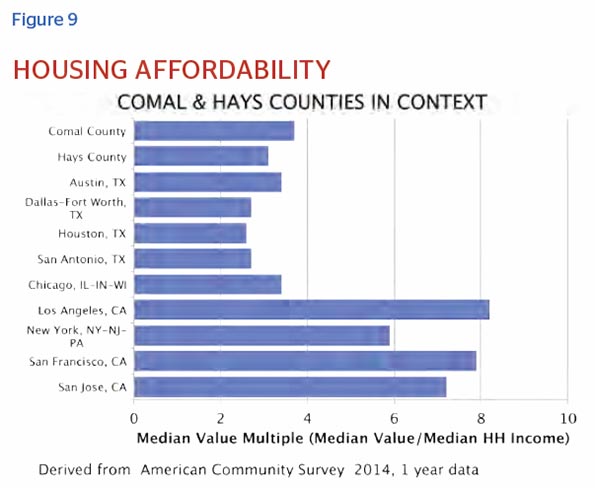

Home prices constitute an advantage for most Texas cities, but even here, the Hays-Comal hub provides even a higher level of affordability. Low taxes and low housing prices make a very convincing case for companies, and individuals, coupled with strong job growth.

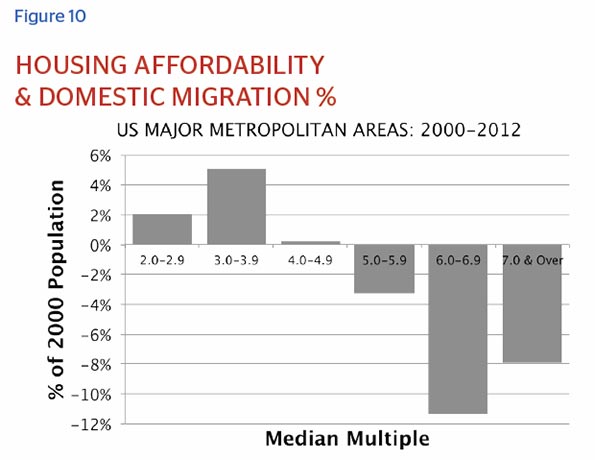

Housing affordability has become one of the key determinants that attracts new migrants to a region. Those areas with high prices relative to incomes tend to lose migrants while those with lower costs — a median multiple of four or less — tend to attract newcomers.

The Future of the San Marcos Corridor: A New Start for Texas?

Lee Graham, President of Mensor LP, a market leader in pressure calibration that moved from Houston in 1978, suggests, “There’s a lot of similarities between what happened with Dallas and Fort Worth 30 years ago with all the communities that filled in between there…. It all developed and filled in.” He went on to say that there is more industry coming on line in the Corridor – even talks about the viability of a future regional airport in Hays or Caldwell County.

Austin’s Culture Map prognosticated recently with the headline “Could Austin and San Antonio be the Next Dallas-Fort Worth?” They interviewed Austin entrepreneur, author, and speaker Gary Hoover who thinks that by 2050 the US Census Bureau will label Austin and San Antonio as precisely this kind of meg-metro area. He notes: “Just the natural growth of the two cities will cause them to collide”.

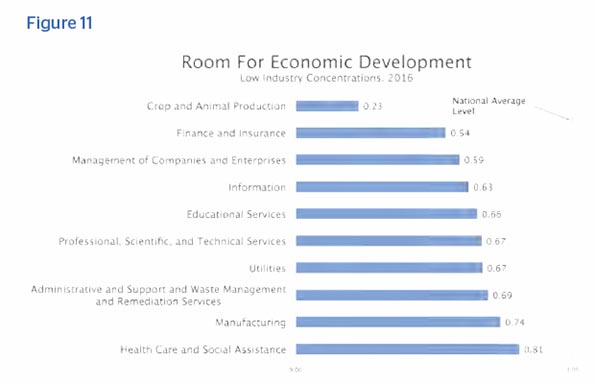

However, for this vision to become reality, there needs to be greater focus on higher paying jobs in business and professional services, manufacturing and technology. Today Hays and Comal County employment is concentrated in construction (including residential and multifamily), retail trade, accommodation and food services and arts, entertainment and recreation -which has fueled the 37% job growth from 2006-2016. Yet, as we have seen above, the fastest growing sectors are in higher-wage, skilled and technical fields. Despite growth in these fields, the area still lags the national average in many key fields like information, management of enterprises, finance and professional, business and technical services.

It is critical to note that the Corridor — particularly the Hays-Comal area — has only recently emerged from an essentially rural past. The key is to make sure that this pastto-the-future transition is tilted towards higher wage, high skilled sectors.

Yet the past does not define the future. Silicon Valley was largely agricultural as late as the 1960s and Raleigh-Durham even later. In contrast Boston’s 128 beltway grew amidst the oldest industrial area in North America, and yet ultimately lost preeminence to the Valley.

The formula that needs to be applied here is forward looking. An agrarian past is no barrier, and may even, to some extent, be an advantage to a region that wants to capture expanding growth from already strong metropolitan economies. The room to expand, lower cost of living associated with less developed economies, and a commitment to preservation of some open space could prove advantageous over the long term.

Key Future Challenges

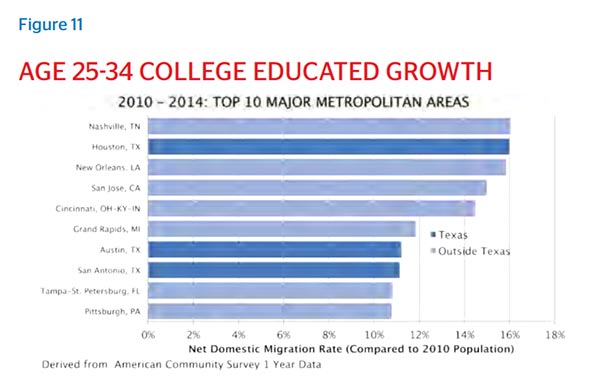

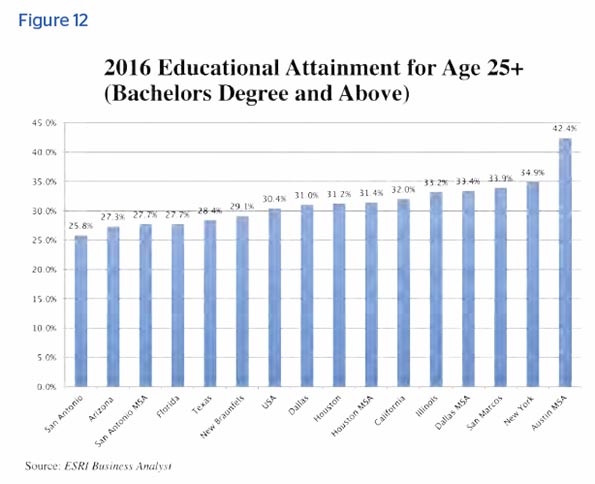

However, just being at the right place at the right time may not be enough. Hays and Comal Counties face many challenges that must be overcome to achieve long-term success. Education has been a big part of all high-tech corridor successes, and Texas State University is certainly a piece of it. But there is also the challenge of training the existing workforce; although improving, the education level of the counties remains below national standards but competitive to the city and county comparisons nearby (see charts 1 and 2). Efforts to upskill the existing workforce will be critical in the future. Just as important is keeping up with infrastructure needs, particularly transportation.

Perhaps the greatest vulnerability of the corridor lies with educational attainment. Although the Austin area is very strong, and well above the national average, the San Antonio region is lagging, as is New Braunfels. In contrast, in large part due to Texas State, San Marcos is above the national average in educational attainment. Expanding the area with high concentrations of college educated people seems a critical step to fulfilling the vision of a thriving Corridor between Austin and San Antonio, and the emergence of Hays and Comal as key players in the new regional configuration.

Fortunately, there are positive efforts and activity in all three areas.

The Greater San Marcos Partnership, according to President Adriana Cruz, has developed a five-year regional economic development strategy (Vision 2020) aimed at growing the region’s economy to attract the high skilled and wage jobs critical to the region’s future.

Since 2006, ten new schools have opened in the four Hays County School districts: Hays, San Marcos, Wimberley and Dripping Springs. Three new schools are to open soon in both the Hays and Dripping Springs school districts.

In Hays County the three workforce development players are Gary Job Corps Center (US Department of Labor), Workforce Solutions Rural Capital Area (multi county community partnership) and Austin Community College (ACC – Hays County falls into their 7,000 square mile service area). Texas State University was recently added to this roster having been named part of the Tech Hire community by the White House. TechHire is designed to train and develop a homegrown information technology workforce that includes ACC, Capital and Rural Capital Workforce Solutions, the City of Austin and the Greater San Marcos Partnership.

In Comal County, the Central Texas Technology Center in New Braunfels is undergoing a 25,000 square foot expansion (opening for classes in 2016) that will double the size. This is part of the Alamo Community College District. Schools in both Comal school districts have been building new schools at a rapid rate. Comal County has had seven new schools come on line since 2006 with four more due to open within the next few years.

Then there is the challenge of infrastructure and transportation. Two major highways serve the region. One is I-35, connecting San Antonio to New Braunfels to San Marcos to Kyle to Buda to Austin. The other is State Highway 130, a 90-mile toll way connecting Seguin to Lockhart to North Austin – and boasting an 85 miles per hour speed limit. Capacity is presently adequate, but future growth may put strain on these facilities. Failure to expand infrastructure has already produced traffic problems in Austin.

There is an ongoing discussion of a commuter rail line connecting Austin to San Antonio that would serve San Marcos. The proposal suffered a serious setback when Union Pacific elected not to support it, and the history of new rail projects is not necessarily encouraging.

If the area can continuously improve these critical must-haves – work force, education and transportation – the trajectory for the area seems to be very positive indeed. The corridor has many things that are likely to accelerate its growth in the years ahead: the continued growth of Austin and San Antonio, the attraction of the Hill County, Texas State University’s emergence and, the overall business climate of Texas. Of course many things could change but the future looks bright for now.

When the future becomes the past, we’ll know if we’re right.

John C. Beddow served as publisher of the Houston Business Journal from 1998 to last year. He successful turned the HBJ fromjust a weekly print product to a 24/7 digital first multi-platform business news channel. He serves on the advisory board of the Houston Technology Center and a recently started his own consulting company – Real Time Consulting, specializing in sales, marketing, media relations and project management. He lives part time in the Hill Country.

Jim LeSage received his PhD in economics from Boston College and a Master’s degree from University of Toledo, where he was a faculty member from 1988 to 2005. Since 2006 he has been the Jerry and Linda Gregg Fields Endowed Chair in Urban & Regional Economics at Texas State University. He is a Fellow of the Regional Science Association International, Spatial Econometrics Association and Southern Regional Science Association, and a past president of the North American Regional Science Council. He has published over 100 scholarly journal articles, and is co-author with R. Kelley Pace of a 2009 book entitled Introduction to Spatial Econometrics. His research has received past support from the National Science Foundation, and he has given workshops on spatial econometrics in Austria, China, France, Germany, Portugal, Spain and several American universities.

Top photo: Larry D. Moore [CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons