Free markets are out of vogue. The unfortunate lesson that policymakers have learned over the past two years is that a big, brainy government that supposedly creates jobs is superior to irrational, faceless markets that just create catastrophic errors. So Washington has seized on the financial and economic crises to enlarge its role in managing the economy—controlling the insurance giant AIG, for example, and trying to maintain high housing prices through tax credits and “mortgage modification” programs.

But when it comes to central economic planning, New York City and State are way ahead of the feds. Empire State politicians from both parties already believe that it’s their responsibility to replace people and businesses in allocating the economy’s resources. They’re even confident that their duty to design a perfect economy trumps their constituents’ right to hold private property. Three current cases of eminent-domain abuse in New York show how serious they are—and how much damage such government intrusiveness can wreak.

Brooklyn’s Prospect Heights, industrial and forlorn for much of the late twentieth century, was looking better by 2003. Government was doing its proper job: crime was down, and the public-transit commute to midtown Manhattan, where many Brooklynites worked, was just 25 minutes. That meant that the private sector could do its job, too, rejuvenating the neighborhood after urban decay. Developers had bought 1920s-era factories and warehouses and converted them into condos for buyers like Daniel Goldstein, who paid $590,000 for a place in a former dry-goods warehouse in 2003. These new residents weren’t put off by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s railyards nearby, and they liked the hardwood floors and airy views typical of such refurbished buildings. They also settled in alongside longtime residents in little houses on quiet streets. Wealthier newcomers joined regulars at Freddy’s, a bar that predated Prohibition. Small businesses continued to employ skilled laborers in low-rise industrial buildings.

But Prospect Heights interested another investor: developer Bruce Ratner, who thought that the area would be perfect for high-rise apartments and office towers. Ratner didn’t want to do the piecemeal work of cajoling private owners into selling their properties, however. Instead, he appealed to the central-planning instincts of New York’s political class. Use the state’s power to seize the private property around the railyards, he told Governor George Pataki, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, and Brooklyn borough president Marty Markowitz. Transfer me the property, and let me buy the railyards themselves below the market price. I’ll build my development, Atlantic Yards, around a world-class basketball arena.

New York, in short, would give Ratner an unfair advantage, and he would return some of the profits reaped from that advantage by creating the “economic benefits” favored by the planning classes. Architecture critics loved Frank Gehry’s design for the arena. Race activist Al Sharpton loved the promise of thousands of minority jobs. The Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (Acorn) loved the prospect of administering the more than 2,000 units of “affordable” housing planned for the development, as well as the $1.5 million in loans and grants that Ratner gave it outright. When the state held public hearings in 2006 to decide whether to approve Atlantic Yards, hundreds of supplicants, hoping for a good job or a cheap apartment, easily drowned out the voices of people like Goldstein, who wanted nothing from the government except the right to keep their homes.

Can New York legally seize private property and transfer it to a developer purely for economic development? The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution allows the government to take property for a “public use,” long understood to mean such things as roads and railways, so long as it makes “just compensation” for them. Starting around the 1930s, a number of court cases began to broaden “public use” to include more nebulous “public purposes,” such as slum clearance. And in 2005, in Kelo v. New London, the Supreme Court decided that these “public purposes” could even include economic development. But New York’s constitution theoretically holds the state to a higher standard. In 1967, Empire State voters voted not to add a “public purpose” clause to their constitution, preferring to stick with the stricter requirement of “public use.”

The state hasn’t let this inconvenience derail its plans for Prospect Heights, however. For seven decades, courts have let New York seize and demolish slum housing if it’s blighted—which New York State defines as “substandard” and “unsanitary.” So the Urban Development Corporation (UDC), a public entity of New York State, decided that the “public use” of Atlantic Yards would be blight removal. The city had already designated part of the neighborhood as “blighted” 40 years earlier, long before its resurgence. As for the rest, the UDC commissioned consultants—previously employed by Ratner—who soon returned the requisite blight finding.

But wait, you say: people don’t buy half-million-dollar apartments in “substandard” or “unsanitary” neighborhoods. You’re right; that’s why the consultants had to stretch. In the 1930s, as Goldstein’s attorney, Matthew Brinckerhoff, pointed out, “substandard” and “unsanitary” meant “families and children dying from rampant fires and pestilence” in tuberculosis-ridden firetraps. In 2006, by contrast, the UDC’s consultants found “substandard” conditions in isolated graffiti, cracked sidewalks, and “underutilization”—that is, when property owners weren’t using their land to generate the social and economic benefits that the government desired.

In New York, this creative definition of blight is the new central-planning model. Consultants have also cited “underutilization” in West Harlem, where the city’s Economic Development Corporation wants to take land from private owners and hand it to Columbia University for an expansion project. Says Norman Siegel, who represents the owners: “A private property owner has the right to determine the best productive use of his property. It’s not a right to be ceded to any government.”

And in Queens, the Bloomberg administration is preparing a similar argument to grab swaths of Willets Point, an area adjacent to Citi Field that’s populated with auto-repair shops. The city’s recent “request for qualifications” from would-be developers drew a sharp response from the people who owned the land: “We . . . hold the most significant qualification of all: we own the properties. We are motivated to improve and use our own properties, consistent with the American free market system. We would have done so in spectacular fashion already, had the city upheld its end of the bargain by providing our neighborhood with essential services and infrastructure.” Instead, the city has done the opposite, letting streets disintegrate into ditches to bolster its blight finding. The perversity is astonishing: rather than doing its own job of maintaining public infrastructure and public safety, the government wants to do the private sector’s job—and is going about it by starving that private sector of public resources.

Property owners have looked to the judiciary to check the overweening grasp of the legislative and executive branches. But courts can be wrong for longer than it takes to save a neighborhood. In Brooklyn, Goldstein and his neighbors have lost their lawsuits—most recently, in New York’s highest court, the court of appeals. In November, the court decided 6–1 that “all that is at issue is a reasonable difference of opinion as to whether the area in question is in fact substandard and insanitary. This is not a sufficient predicate for us to supplant [the state’s] determination.” The court essentially abdicated its duty to protect property owners from the governor and the Legislature.

Nine days later, the West Harlem owners fared better in a lower court. The first department of the state supreme court’s appellate division found, 3–2, that the blight studies that the city and state had commissioned to justify their rapacity were “bereft of facts”—and further tainted by the fact that one blight consultant also worked for Columbia. The blight designation “is mere sophistry,” the majority concluded, “hatched to justify the employment of eminent domain.” The court further noted that “even a cursory examination of the study reveals the idiocy of considering things like unpainted block walls or loose awning supports as evidence of a blighted neighborhood. Virtually every neighborhood in the five boroughs will yield similar instances of disrepair.”

The selective and arbitrary process that deems one neighborhood blighted while leaving a similar neighborhood alone also violates due process, the justices went on, as “one is compelled to guess what subjective factors will be employed in each claim of blight.” Another violation: the government responded poorly to property owners’ document requests under the state’s freedom of information law, hampering their right to mount a solid case. Such requests are particularly important in eminent-domain cases because New York property owners don’t enjoy the right to a trial with a discovery phase, but must go straight to appeals court—a seventies-era “reform” meant to speed up development projects.

The Harlem owners were able to convince the lower court partly because they had commissioned their own “no-blight” study. “We said, ‘Let’s create our own record . . . as a counterweight,’ ” said Siegel. The owners also presented as evidence a government study, performed before Columbia showed interest in the land, that West Harlem was revitalizing itself. This is all very well—but property rights shouldn’t depend on owners’ creativity and resourcefulness in proving beyond all reasonable doubt that their land isn’t blighted.

Further, the lower-court ruling is a tenuous victory. The case is proceeding to the court of appeals, and though Siegel is “cautiously optimistic” that it will rule in his clients’ favor, there’s no way to be sure. Meantime, Goldstein and fellow residents and business owners in Brooklyn have asked the court of appeals to reconsider its Atlantic Yards ruling after it rules on Harlem. But the starkly different decisions in the Harlem and Brooklyn cases, coming so close together, have pointed up the need for the Legislature and Governor David Paterson to create clear standards for the government’s power to seize property.

An obvious step is to dispense with “underutilization” as a justification for a taking. As the court noted in the Harlem case, “the time has come to categorically reject eminent domain takings solely based on underutilization. This concept . . . transforms the purpose for blight removal from the elimination of harmful social and economic conditions . . . to a policy affirmatively requiring the ultimate commercial development of all property.”

But the state should go even further and eliminate blight itself as a justification for property seizure. Since the sixties, when creeping blight seemed to threaten the city’s existence, New York has learned that the real remedy for “substandard” conditions is good policing and infrastructure, which create the conditions for people and companies to move to neighborhoods and improve them. As for 1930s-style “unsanitary” conditions, modern health care, infrastructure, and building codes have eliminated them. Today, the biggest risks to public health are often on government property: dangerous elevators in public housing, for instance, or the 2007 fire that killed two firefighters in the Deutsche Bank building in lower Manhattan, owned by the city and state since 9/11. Unless it needs property to build a road, a subway line, a water-treatment plant, or a similar piece of truly public infrastructure—or unless a piece of land poses a clear and present danger to the public—the state should keep its hands off people’s property.

Eminent-domain abuse, dangerous though it is, is a symptom of a deeper problem: government officials’ belief that central planning is superior to free-market competition. That’s what New York has decided in each of its current eminent-domain cases. In Brooklyn, high-rise towers and an arena are better than a historic low-rise neighborhood; in Harlem, an elite university’s expansion project is better than continued private investment; and in Willets Point, Queens, almost anything is better than grubby body shops.

To cure yourself of the notion that the government can do better than free markets in producing economic vitality, stroll around Atlantic Yards. You’ll walk past three-story clapboard homes nestled next to elegantly corniced row houses—the supposedly blighted residences that the state plans to demolish. You’ll see the Spalding Building, a stately sporting-goods-factory-turned-condo-building that, thanks to Ratner and his government allies, has been slated for demolition and now stands empty. You’ll peer up at Goldstein’s nearly empty apartment house, scheduled to be condemned and destroyed.

And you’ll see how wrecking balls have already made the neighborhood gap-toothed. A vacant lot, for example, now sprawls where the historic Ward Bakery warehouse was, until recently, a candidate for private-sector reinvestment. Today, Prospect Heights finally shows what the state and city governments want everyone to see: decay. The decay, though, isn’t the work of callous markets that left the neighborhood to perish. It’s the work of a developer wielding state power to press property owners to sell their land “voluntarily.” It’s also the result of a half-decade’s worth of government-created uncertainty, which stopped genuine private investment in its tracks.

Such uncertainty offers a crucial lesson to the rest of the nation, and not just in the area of eminent domain. Whenever government fails to confine itself to a limited role in the economy, it creates similar uncertainty. Even when the results aren’t as poignantly obvious as they are in Brooklyn, the private economy suffers—whether it’s financial or auto bailouts unfairly benefiting some firms at the expense of others, or mortgage bailouts unfairly benefiting some home buyers at the expense of others. Free markets may be imperfect, but they’re far better than the alternative—the blight of arbitrary government control and the uncertainty that it creates.

This article originally appeared at City Journal. Research for this article was supported by the Brunie Fund for New York Journalism.

Nicole Gelinas, a City Journal contributing editor and the Searle Freedom Trust Fellow at the Manhattan Institute, is a Chartered Financial Analyst and the author of After the Fall.

Photo: Tracy Collins

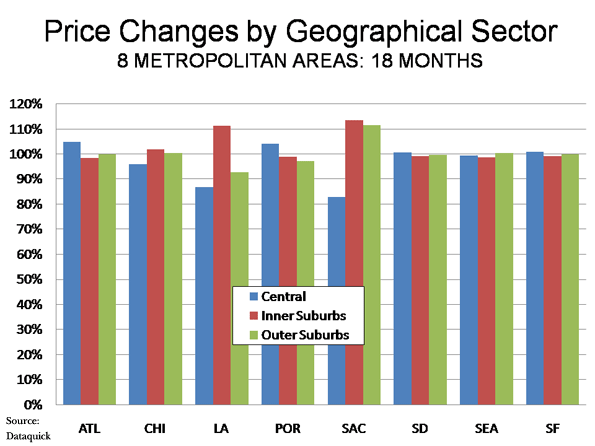

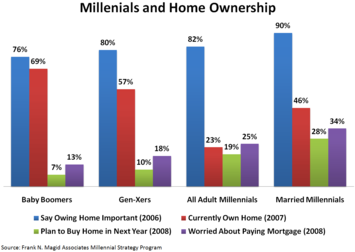

This pattern will continue to the mid-21st century. The reasons are not hard to identify: Suburbs experience faster job and income growth, far lower crime rates (roughly one-third) and much higher rates of home ownership. While cities will always exercise a strong draw for younger people, the appeal often proves to be short-lived; as people enter their 30s and beyond, they generally prefer suburbs. This pattern will become more pronounced as the huge millennial generation — those born after 1983 — enters this age cohort.

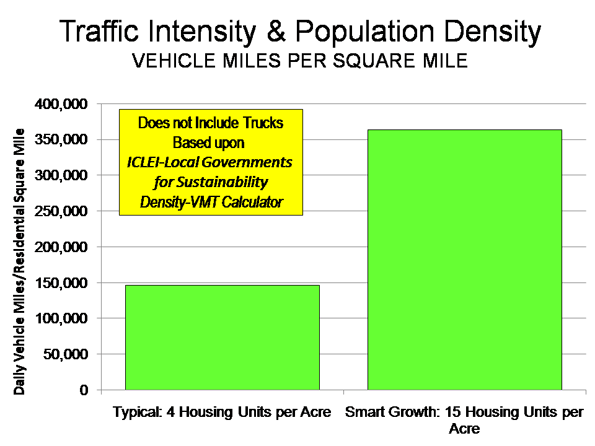

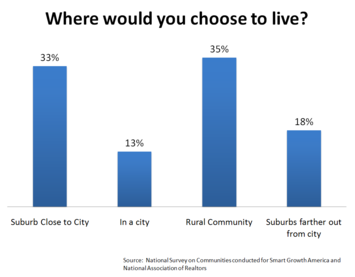

This pattern will continue to the mid-21st century. The reasons are not hard to identify: Suburbs experience faster job and income growth, far lower crime rates (roughly one-third) and much higher rates of home ownership. While cities will always exercise a strong draw for younger people, the appeal often proves to be short-lived; as people enter their 30s and beyond, they generally prefer suburbs. This pattern will become more pronounced as the huge millennial generation — those born after 1983 — enters this age cohort. Surveys of housing preferences consistently show that if given the choice, most Americans, particularly families, will still opt for a place with a spot of land and a little breathing room. And despite the coming population growth, most Americans will probably continue to resist being forced into density, and even with 100 million more people, the country will still be only one-sixth as crowded as Germany.

Surveys of housing preferences consistently show that if given the choice, most Americans, particularly families, will still opt for a place with a spot of land and a little breathing room. And despite the coming population growth, most Americans will probably continue to resist being forced into density, and even with 100 million more people, the country will still be only one-sixth as crowded as Germany.. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, released in Febuary, 2010.