By Richard Reep

Regions have a bad habit of getting into ruts. This is true of any place that focuses exclusively on one industry – with the possible exception of the federal government, which keeps expanding no matter what. This reality is most evident in places like Detroit, but it also applies to one like Orlando, whose tourist-based economy has been held up as a post-industrial model.

This has not been helped by recent diktats from DC Central Control. As reported in the Wall Street Journal, the Ephemeral City, among others, has now been branded a Sybaris. Private interests continue to book conferences in Central Florida due to its good value, but the closed circle of federal government has prudishly proscribed the family leisure capital of the world in favor of destinations like Chicago. Central Florida’s chagrined congressional delegation, caught in reaction mode, will fight to remove this ban, but the damage has been done. A cold new era has firmly settled into the Sunshine State’s former playground.

Since welcoming Walt Disney with open arms in 1964, Orlando proudly built its reputation as a family leisure destination. With over 116,000 hotel rooms, Orlando competes with Las Vegas in both the national and global tourism market. Indeed, Europeans, Middle Easterners, Asians, and Latin Americans make Orlando their playground, and if physical evidence is needed, the exquisitely messy honky-tonk of North International Drive testifies to this reality.

Many couldn’t fault this strategy – at least until until now. Orlando’s mania for tourism, supported by local, regional and state policies, yielded growth beyond the wildest dreams of this once-sleepy agricultural town at a railroad crossing among orange groves and cattle ranches.

But in the current economy, leisure can be seen as a waste of time and money. “I think Orlando got put on the list of not to go because of the perception that it is a resort and vacation area,” read a July email from a Department of Agriculture employee to an Orlando conference planner. Business in Central Florida has slowed to a trickle, anxiety is increasing and doors are closing. It seems that Orlando’s tourism bubble has popped with visitorship dropping from a high of nearly 50 million in 2005, to a projected high barely above 43 million in 2009, and while civic leaders are huffing and puffing to blow it back up again, Central Florida’s leisure industry is a shadow of its former boisterous self.

Corporate trainers, state and local government conferences, not-for-profits, trade associations, and incentive groups still find Central Florida a decent place to hold meetings. Airfare is cheap, the vast quantity of hotel rooms makes for competitive rates. The renewed emphasis on bringing the family along makes Orlando a natural fit for many groups seeking a destination, especially in the winter. They may book rooms in more affordable Osceola County rather than pricey Orange County, but are still a few minutes’ drive from Disney’s front door, the beach, and dozens and dozens of food and shopping outlets. Some hotel owners are even contemplating new meeting rooms to keep up with shifting demand.

The new mood in Washington, however, does not favor Orlando as a destination. Central Florida may be a good value, but this is irrelevant to the equation, for it is the overriding perception of Orlando that seems to worry our national government’s travel planners. And this perception tells us quite a bit about the real thinking that is happening at the federal level.

If the new policy were to plan trips only to destinations under the median cost, it would send a message that government does not want to waste money. It might also send federal conferences to destinations in overlooked parts of America that could open beltway eyes to the bleak turmoil enveloping so much of the country, despite the steady drumbeat of recovery news.

Meanwhile, sellers already know that Washington is really the only game in town, as businesses turn towards grant programs, rebates, and other incentives to backfill lost private sector revenue in goods and services. But if one looks closely at the actual investment pattern, Washington seems to favor the financial market, green energy, and possibly its own future health care program – none of which plays to Orlando’s strengths. This extremely narrow set of interests belies a harsh ideology, as harsh as the ideology it replaced, and as bad for the average citizens of America.

Yet for all this, Central Florida should share some of the blame. Orlando cursed itself by growing around a single specialty, rather than a diverse set of interests. Favoring theme parks over agriculture was certainly an opportunistic decision, but reinforcing tourism and ignoring all other investment has proved a vast miscalculation. The Sunshine State could have been #1 in solar energy research by now, making it Obama’s darling. So Central Florida, without any other true industry, now grovels at the government’s feet to restore itself into good graces and allow a National Park Service meeting to take place at the Ramada Inn again. It is likely that Orlando will be shut out of this closed circle for some time to come.

Central Florida’s best hope lies in a recovery of the private sector economy, a regained sense of profitability by corporations, and a renewed faith in the future by individuals. Lacking these now, Central Florida hibernates, its giant engines of escapism in low gear, mothballed, or abandoned.

One almost hopes The Recovery will be delayed long enough to suffer some sense into the politicians and business leaders who can diversify the economy of the region. After all many of things that attract tourists – low costs, good infrastructure, warm weather – should also lure entrepreneurs, skilled workers and capital, foreign and domestic. You wonder why our leaders have not yet thought of this, or put a plan to diversify into action.

Richard Reep is an Architect and artist living in Winter Park, Florida. His practice has centered around hospitality-driven mixed use, and has contributed in various capacities to urban mixed-use projects, both nationally and internationally, for the last 25 years.

Photo by Carlos Cruz.

Environmentalism has further accelerated the trend for the shrinking of the British home. The emphasis upon the Rogers-style compact city has been trumpeted by the Green Party and other environmental lobby groups because higher densities and small build theoretically cause less carbon emissions and use up less non-renewable sources of energy.

Environmentalism has further accelerated the trend for the shrinking of the British home. The emphasis upon the Rogers-style compact city has been trumpeted by the Green Party and other environmental lobby groups because higher densities and small build theoretically cause less carbon emissions and use up less non-renewable sources of energy.  Union Square, San Francisco – Despite an expensive redesign nearly five years ago, Union Square is still not the central urban gathering space for San Francisco. Although it does serve as an incidental focus of pedestrian activity within the immediate neighborhood, the primarily hardscaped design is too fussy and too formal to encourage casual passive use and extended stays, except, perhaps, within limited zones at the fringes. The little available seating is poorly designed, intended to prevent homeless use rather than to promote use by casual park visitors. Primarily a concrete space with grass at the corners, Union Square lacks the “warmth” that makes such spaces comfortable. Imagine a Union Square with a great lawn in the middle, rather than cold (and expensive) hardscape.

Union Square, San Francisco – Despite an expensive redesign nearly five years ago, Union Square is still not the central urban gathering space for San Francisco. Although it does serve as an incidental focus of pedestrian activity within the immediate neighborhood, the primarily hardscaped design is too fussy and too formal to encourage casual passive use and extended stays, except, perhaps, within limited zones at the fringes. The little available seating is poorly designed, intended to prevent homeless use rather than to promote use by casual park visitors. Primarily a concrete space with grass at the corners, Union Square lacks the “warmth” that makes such spaces comfortable. Imagine a Union Square with a great lawn in the middle, rather than cold (and expensive) hardscape. Market Street, San Francisco – Punctuated by intermittent triangular plazas along most of its downtown stretches, portions of Market Street’s public space are more the domain of homeless panhandlers than workers, residents, strollers, and the like (it should be noted, however, that some parts of Market Street, such as in the Financial District, can be pleasant at times). The plazas, quality architecture, and mix of uses create potential. But the pedestrian environment discourages extended dwell times, except by the homeless, panhandlers and drug dealers, many of whom, the city has documented, commute daily to Market Street from elsewhere in the Bay Area. The design offers little in the way of seating options and softscape. Sanitation and maintenance need to be substantially upgraded and programming is needed.

Market Street, San Francisco – Punctuated by intermittent triangular plazas along most of its downtown stretches, portions of Market Street’s public space are more the domain of homeless panhandlers than workers, residents, strollers, and the like (it should be noted, however, that some parts of Market Street, such as in the Financial District, can be pleasant at times). The plazas, quality architecture, and mix of uses create potential. But the pedestrian environment discourages extended dwell times, except by the homeless, panhandlers and drug dealers, many of whom, the city has documented, commute daily to Market Street from elsewhere in the Bay Area. The design offers little in the way of seating options and softscape. Sanitation and maintenance need to be substantially upgraded and programming is needed. Proper seating, adequate lighting, and extensive horticultural displays would serve to populate these public spaces. Proper management and maintenance would ensure long-term success. Places such as Bryant Park in Midtown Manhattan, itself the beneficiary of a remarkable turnaround masterminded by Daniel Biederman of the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation, have shown what visionary management can do to struggling urban public spaces. [Kozloff worked for BRV Corp., Biederman’s private consulting company that is independent of the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation, from 2001-2004.] Although once run on a city budget of $200,000, Bryant Park is now managed on a privately-funded budget. Biederman turned Bryant Park – once the domain of drug dealers and other such undesirables – into Manhattan’s premier address without using public coffers.

Proper seating, adequate lighting, and extensive horticultural displays would serve to populate these public spaces. Proper management and maintenance would ensure long-term success. Places such as Bryant Park in Midtown Manhattan, itself the beneficiary of a remarkable turnaround masterminded by Daniel Biederman of the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation, have shown what visionary management can do to struggling urban public spaces. [Kozloff worked for BRV Corp., Biederman’s private consulting company that is independent of the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation, from 2001-2004.] Although once run on a city budget of $200,000, Bryant Park is now managed on a privately-funded budget. Biederman turned Bryant Park – once the domain of drug dealers and other such undesirables – into Manhattan’s premier address without using public coffers.

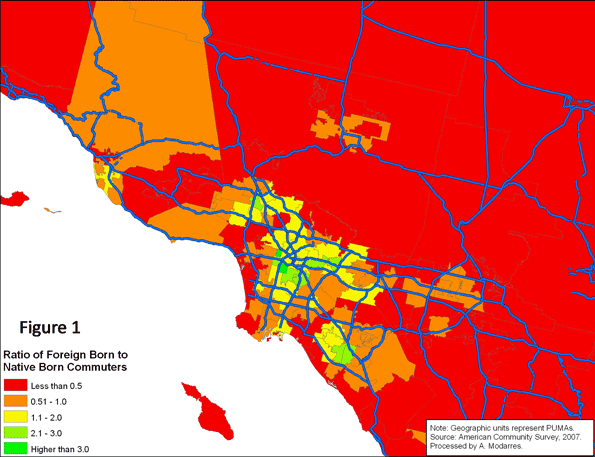

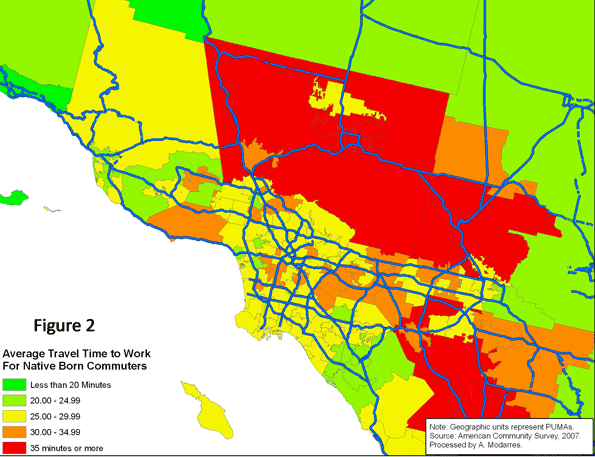

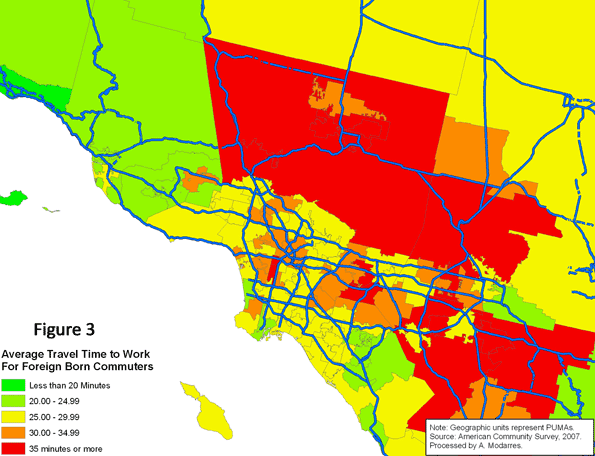

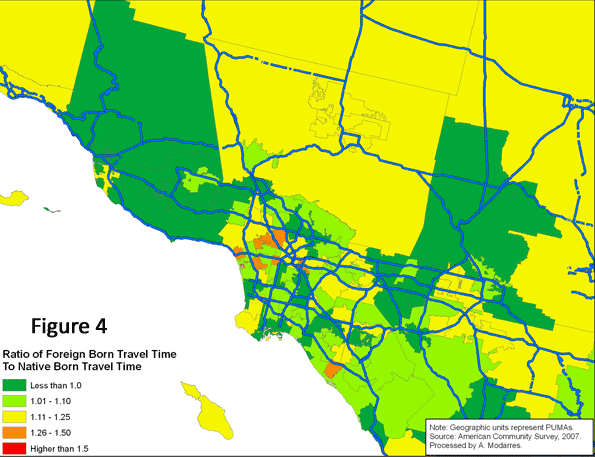

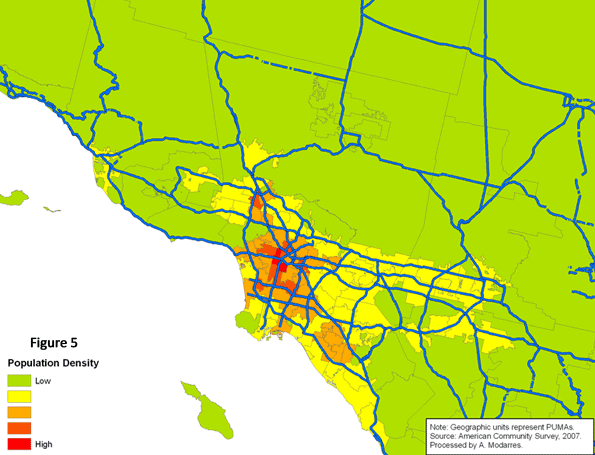

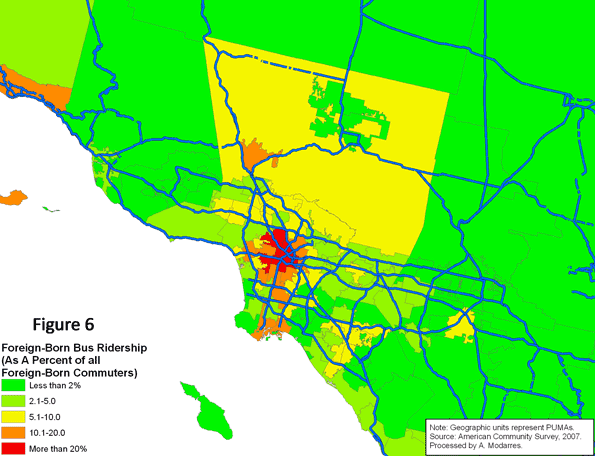

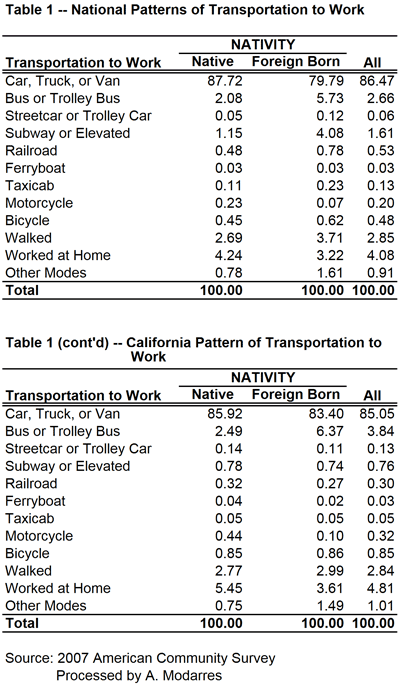

Based on the 2007 American Community Survey, 117.3 million native-born and 21.9 million foreign-born individuals commuted to work. As Table (1) illustrates, a higher percentage of immigrants rode buses (5.7% vs. 2.1%) and subways (4.1% vs. 1.2%) and many walked to work (3.7% vs. 2.7%). A much smaller percentage drove to work (79.8% vs. 87.7%). Unfortunately, despite their higher usage of alternate means of transportation to work, or perhaps because of it, the commute to work time was on average longer for the foreign-born commuters than their native-born counterparts (28.8 minutes versus 24.7).

Based on the 2007 American Community Survey, 117.3 million native-born and 21.9 million foreign-born individuals commuted to work. As Table (1) illustrates, a higher percentage of immigrants rode buses (5.7% vs. 2.1%) and subways (4.1% vs. 1.2%) and many walked to work (3.7% vs. 2.7%). A much smaller percentage drove to work (79.8% vs. 87.7%). Unfortunately, despite their higher usage of alternate means of transportation to work, or perhaps because of it, the commute to work time was on average longer for the foreign-born commuters than their native-born counterparts (28.8 minutes versus 24.7).

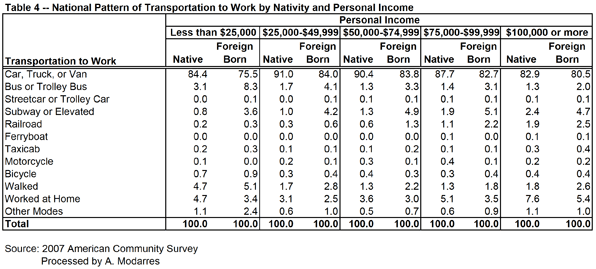

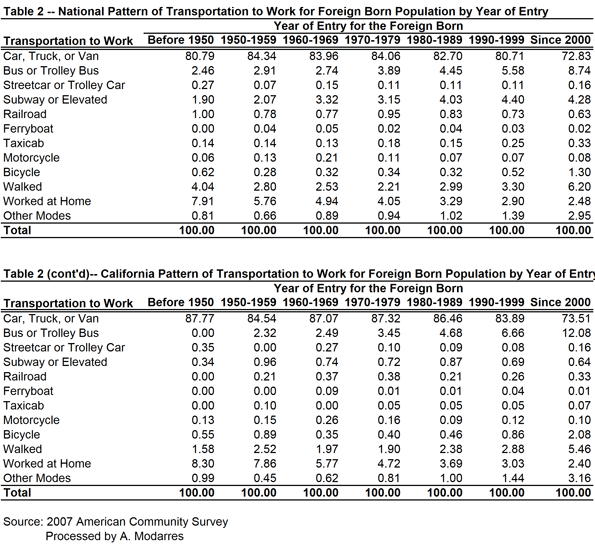

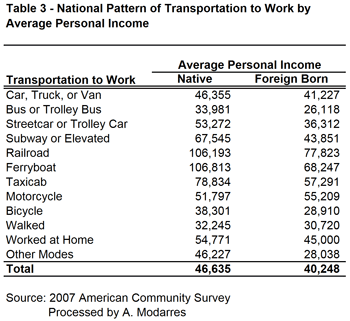

Even so, their rates are still slightly better than the native-born (compare Tables 1 and 2). This may be in part because of their lower incomes (see Table 3) yet at every level of income they are still more likely to take transit. Table (4) illustrates this point by grouping commuters into income categories and their nativity. In every income category, immigrants use their cars less and are more likely to use public transportation, even though their car ridership increases with income.

Even so, their rates are still slightly better than the native-born (compare Tables 1 and 2). This may be in part because of their lower incomes (see Table 3) yet at every level of income they are still more likely to take transit. Table (4) illustrates this point by grouping commuters into income categories and their nativity. In every income category, immigrants use their cars less and are more likely to use public transportation, even though their car ridership increases with income.