Treasury Secretary Ken Henry’s recent address to business economists was an apt prism through which to survey Sydney’s immediate past and distant future. According to reports, he said ‘the [Chinese] resources boom had produced a “two-speed” economy, with unemployment rising in the south-eastern states but falling in the west and north’. Dr Henry is reported to have told his Sydney audience, ‘I don’t think everybody in this room should be moving to Perth. But let me make this prediction: some of you will’.

These comments serve as a reminder of how quickly the ground shifts in an open and dynamic economy. It wasn’t so long ago that New South Wales, dominated by Sydney, was dubbed the powerhouse of Australia’s extended boom.

Even the most elaborate attempts at urban planning can be superseded by events. After all, modern Sydney was itself, until recently, shaped by forces that outpaced the bureaucrats and planners. These forces are assuming a new dynamic in the conditions described by Dr Henry. Competition from the interstate resources boom is a now major factor driving state politics, together with slowing jobs and property markets and nagging infrastructure constraints. All are feeding the momentum for revitalization – for a new phase of urban growth that will push the limits advocated by planners, environmentalists and others campaigning to turn the city’s socio-economic tide.

The suburban economy

There is surprisingly little acknowledgement that, overall, the transformation of suburban Sydney in the wake of globalisation has been a success story. Over the last twenty years, the middle to outer suburbs adapted to volatile domestic and international environments, as well as technological change at breakneck speed, with an effective model of economic development. The key point is that this had more to do with the interplay of space and mobility than good planning.

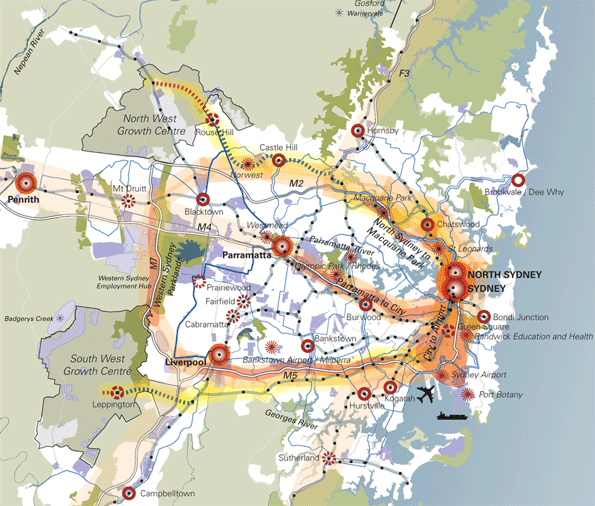

By no means was this inevitable. Sydney could have succumbed to the downside of what urban theorists call the ‘world city’ phenomenon. According to the research group Globalisation and World Cities (GaWC), world cities are major international hubs with stronger ties to the global economy in terms of capital flows, trade and movement of people and information than to their own hinterlands. GaWC ranks Sydney in the second or ‘beta’ echelon of world cities, along with places like San Francisco and Mexico City (Melbourne is ranked in the third or ‘gamma’ echelon). Hence Sydney’s ‘global arc corridor’, which stretches from Macquarie Park south to the CBD’s gleaming towers and onto Sydney Airport and Port Botany, hosts the cream of the country’s finance, legal and business services, information technology, engineering and marketing industries.

Some world cities are distinguished by vast disparities in wealth and economic opportunity – between such globally oriented zones, sucking up the region’s capital, infrastructure capacity, skills base and government services, and stagnant hinterlands inhabited by struggling workers in declining, marginal industries or masses of unemployed. But that was not Sydney’s fate.

Why and how did a viable economy develop in the middle to outer suburbs of the city? To answer this question it is necessary to recall some of the constants of Sydney’s recent history. The gradual emergence of global Sydney generated higher land values throughout the inner-city. Consequently, many inner-city land uses associated with nineteenth century transport nodes, such as the light industrial plants, depots and warehouses clustered near the railway junction south of the CBD or along the harbour foreshores of the inner-west were no longer sustainable in the face of escalating demands for office space and gentrification.

Combined with the growth of motor vehicle mobility for passenger and freight transport, particularly since the 1950s, this led to the transfer of many industrial, transport and warehousing activities to cheaper land on the western and south-western fringes. At that stage of the city’s evolution, there were relatively few restrictions on the acquisition of space for these and related purposes. And the growth of road transport relative to maritime and rail sealed the necessary links to international gateways on the eastern seaboard, like Sydney Harbour, Port Botany and the airport.

These trends were intensified by the construction of a road network to service the interstices of Sydney’s nineteenth century ‘hub-and-spokes’ or radial railway lines, culminating in the orbital motorway network (the dreaded ‘tollways’). Not only did motor vehicle mobility facilitate industrial dispersion, but also residential settlement adjacent to the new industrial jobs. The radial railway lines were Sydney’s nineteenth and early twentieth century template; the orbital motorway is the city’s contemporary template.

As in the case of industrial relocation, there were fewer restrictions on residential development for the workers employed in these dispersed industries (this began to change by the mid-1990s). Inexpensive housing, a mild climate, out-door lifestyles and a preference for detached houses on sizeable blocks were also attractions. Over time western Sydney achieved 75 per cent regional employment self-containment, and key travel patterns are now intra-regional.

Later phases of globalisation reinforced this spatial pattern. The rise of global Sydney was a major driver, at least since the early 1980s, of economic policies that favoured the liberalisation of economic activity. Naturally, this had repercussions across the rest of the city. One fundamental outcome was the expansion of services – such as retail – relative to manufacturing and commodities as a proportion of the national economy. The appearance of diverse service industries in the outer suburbs was yet another function of space and mobility. In western Sydney, this was closely associated with the region’s booming population growth. From the 1970s to recent times, western Sydney’s population growth outstripped the rest of the city and country.

By the early 1990s, market oriented reform had ushered in a period of low inflation, interest rates and input costs, the latter having been wrung from difficult reforms to energy and other public utilities. The interaction of steady economic and population growth powered a strong consumer economy linked to settlement of the fringe suburbs. Such areas experienced a boom in residential and commercial construction, and the related demand for household fixtures, appliances and goods.

These conditions unleashed a thriving small business sector in services, operating in a competitive market characterised by low entry barriers (low costs and overheads) and narrow profit margins. This, too, was a by-product of globalisation, as SGS Economics and Planning explain: ‘The concentration of small business activity in NSW (and Sydney) and the more rapid growth in the share of employment in this sector compared with other parts of Australia may reflect the tendency for heightened fragmentation of supply chains in globally engaged economic regions’. Presumably, this is why Mark Latham harped on about ‘the small business-people, the contractors, franchisees and consultants of the new economy’.

While market pressures caused the ‘unbundling’ of service providers, advanced information and communications technologies were integrating head office, back office, manufacturing and distribution activities in land extensive facilities like the 50,000 plus square metre Coles Myer and Coca Cola distribution centres at Eastern Creek, and, in a different way, cutting-edge business and technology parks like Norwest and Macquarie Park. These facilities, contiguous with the orbital motorway, are creatures of space and motor vehicle mobility, and always will be.

That is why the best elements of the NSW government’s City of Cities plan represent responsive rather than prescriptive planning; they reinforce successful trends emerging from the interplay of market forces. Plans for intensive commercial development along orbital motorway corridors, such as the M7 and particularly at its intersection with the M4, dubbed ‘the western Sydney employment hub’, the refocus on important western centres like Parramatta, Liverpool and Penrith as ‘regional cities’, and the series of road-rail transport interchanges (also land extensive) are prime examples.

Its enemies

This vibrant though vulnerable web of socio-economic connections is always at the mercy of global conditions – witness the impact of petrol prices – but also increasingly under challenge from domestic political actors, principally environmentalists, urban planners, some property developers and opinion makers. Their determination to freeze urban boundaries and, as far as possible, reduce mobility to public transport capacity, particularly rail, is hurting Sydney. Hopefully, their influence is gradually receding under Morris Iemma’s leadership.

Environmentalists and planners – two increasingly interchangeable categories – are oblivious to the prospect that their creeping regulations and imposts, and misallocated resources, could unravel the suburban economy. Yet they will always struggle to mobilise public opinion. Their all-purpose pretext, the climate change hypothesis, relies on aggregated data which can’t be used to argue particular cases. Take the NSW government’s recent decision to review the costly ‘energy efficiency building sustainability’ rules. While the Housing Industry Association came to the issue armed with a raft of statistics about price impacts and falling housing starts, green outfits like the Total Environment Centre could do little but sputter the magic words ‘greenhouse’ and ‘global warming’. They were not in a position to show why, how and to what extent this particular decision would exacerbate climate change.

Their other weapon is the peculiar concept of ecological or urban ‘footprint’. This purports to measure how much productive land and water an individual, a city, a country, or humanity requires to produce all the resources it consumes. On this measure, Sydney has a footprint that covers 49 per cent of NSW or 150 times its actual size, so its expansion must be constrained. The notion that wealth can be equated to an amount of land, however, is a throwback to pre-modern times. In advanced economies, wealth creation has more to do with the elaborate transformation of natural inputs, capital accumulation, forms of business organisation and services. And as one scathing writer points out, the concept fails to acknowledge that a stretch of land can be used for several different purposes simultaneously. Nevertheless, this absurd idea continues to pass unmolested into almost every discussion of urban planning, including City of Cities.

If environmentalists are taken seriously at all, it is because they ride on the back of vested interests who benefit from artificially inflated land values, since this is the inevitable consequence of restricting new releases. Alan Moran of the Institute of Public Affairs argues that the reluctance of governments to burst the bubble of housing unaffordability by releasing more land for development can be traced to the undue influence of existing property owners, including powerful developers, who stand to suffer a capital loss if the scarcity value of land is diminished. It is a case of the ‘haves’ depriving the ‘have nots’, such as low income earners and young first home buyers.

Then there are the progressive academics and commentators who insist the suburbs are zones of social alienation, inimical to personal contentment and well-being. Consider the Australian Financial Review’s property writer Tina Perinotto, who opposes sprawl because we can’t afford the ‘psychologists to deal with people who end up in the lonely greenfield sites’, or left-wing writer Natasha Cica, who raves about ‘the aesthetic and ethical slums of McMansion affluenza’, or Sydney Morning Herald planning and architecture writer Elizabeth Farrelly, who calls suburbanisation ‘total-indulgence parenting’, or urban policy academic Brendan Gleeson, who believes ‘shadows of fear and antipathy are spreading across’ the suburbs.

Progressives clearly feel a need to delegitimise suburban life. This stems from their barely suppressed rage against people they can’t control. Like Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, suburban people have strayed too far from civilisation, they contend, and will lose their minds. Yet they fail to explain why surveys indicate an overwhelming preference for detached housing on sizeable blocks, or why the latest Australian Unity Wellbeing Index registers higher rates of happiness amongst suburban people than their inner-city counterparts.

The left’s new poster-boy of urbanism, Gleeson, in particular, leads a tortured existence: he idealises suburbs as the nation’s ‘heartlands’ while hating almost everything about them. Gleeson has latched on to the emergence of so-called ‘gated’ communities as ‘harmful to collective democratic purpose’. This sort of socio-economic segregation is a recognised downside of the ‘world city’ scenario, especially in developing countries. In Sydney, however, it is more likely to mark a transitional stage of historically disadvantaged areas attracting more prosperous residents, eager to replicate the superior amenity of affluent suburbs. To the extent that it heralds the arrival of generally higher living standards in these localities, it is not necessarily the evil denounced by Gleeson.

Of course, the enemies of growth don’t give a damn about the storm clouds perceived by Dr Henry. Sooner or later, however, they will bow to the inevitable: space and mobility made Sydney’s past; they will make the city’s future, if it is to be a future worth having.

This article originally appeared at The New City Journal