This piece by Zelda Bronstein (original to 48hills.org) goes behind the story of the Peninsula planning commissioner who made national news by saying she had to leave town to buy a house for her family.

On August 10, Kate Vershov Downing, a 31-year-old intellectual-property lawyer, set the media aflutter when she posted on Medium a letter to the Palo Alto City Council stating that she was resigning from the city’s Planning Commission because she was moving to Santa Cruz. The reason for her move: She and her 33-year-old husband Steven, a software engineer, couldn’t find a house they could afford to buy in Palo Alto. Downing said that they currently rented a place with another couple for $6,200 a month, and that if they “wanted to buy the same house and share it with children and not roommates, it would cost $2M.”

She reasoned that “if professionals like me cannot raise a family here, then all of our teachers, first responders, and service workers are in dire straits.” The fault, Downing wrote, lies with the Palo Alto council, which “ignores the majority of residents,” who have asked that housing be the city’s “top priority.” Instead, the council approves “more offices” and “a nominal amount of housing,” while paying “lip service to preserving retail that simply has no reason to keep serving the average Joe when the city is affordable only to Joe Millionaires.”

The upshot is a place “where young families have no hope of ever putting down roots” and civic culture is on the decline, thanks to the onslaught of “middle-aged jet-setting executives and investors who are hardly the sort to be personally volunteering for neighborhood block parties, earthquake preparedness responsibilities, and neighborhood watch.”

Downing’s post went viral. Within a week, her story had been picked up by media ranging from the San Francisco Business Times, the Huffington Post, and Curbed to the Washington Post, the L.A. Times, and the Guardian (UK). Thomas Fuller, the San Francisco bureau chief of the New York Times, did an extensive video interview of the Downings in front of their about-to-be-former Palo Alto residence followed by a driving tour of the town. Last week she appeared live on Bloomberg News.

I’d hoped to talk to Kate Downing myself. We’d exchanged emails in February 2015, when I was working on a story about the inaugural forum of SFBARF (San Francisco Bay Area Renters Federation), in which she’d participated as a panelist representing Palo Alto Forward, the pro-development, smart-growth group she co-founded in August 2014.

This time Downing she failed to respond to my repeated requests for an interview. I wonder if her reticence indicated an expectation that I would ask some hard questions.

If so, she was right. Her statements to a generally credulous press and her posts on Medium contain a few good points buried in a jumble of obfuscation, neoliberal dogma, and startling ignorance.

Far more troubling is the generally credulous reception she’s gotten from the media. Only Curbed, the Stanford Political Journal, and the New York Times bothered to interview a member of the Palo Alto council, Mayor Pat Burt. With the Times’ Fuller, Burt rated only a two-sentence quote (no driving tour). Bloomberg News displayed a quotation from Burt stating that the city was “looking to increase the rate of housing growth but decrease the rate of job growth” and then asked Downing if that was “reasonable.” None of her interviewers contacted members of the community who hold opposing views, in particular representatives of the slow-growth group Palo Altans for Sensible Zoning.

Given that Downing appears to have become a prominent spokesperson for millenial market fundamentalism, her ideas and her actions deserve scrutiny. Here’s a start.

Are four bedrooms and two-plus baths necessary to raise a family?

Citing the price of housing, Downing asserted that “professionals like me cannot raise a family” in Palo Alto.

Curbed reporter Adam Brinklow asked: “Why not buy a cheaper place? There are some cheaper places.”

Downing dodged the question. “Sure,” she said, “we could move half an hour away. But if I can afford to move half an hour away to San Mateo, what happens to the people who have to move out of San Mateo?”

Brinklow tried again: “I don’t mean half an hour away, I mean right in Palo Alto. There are cheaper homes. Not very cheap, but not $2.7 million either?

Another dodge: “Well, that comment about the price of the house was really just an anchor for reference. But even if I found a cheaper home, even $2 million is more than I have to spend, and anything less is usually a project. Remember, you can’t take out a loan for construction.”

Okay, but there are non-fixer-uppers with two bedrooms in Palo Alto, presumably large enough for a budding family, that the Downings could afford—which is to say, places selling for what they paid for their new home in Santa Cruz: $1,550,000. The difference is that those places are condos and townhouses.

What Downing didn’t tell Brinklow (and he didn’t ask) is that she and her husband wanted the same kind of house that they were renting in Palo Alto: a 4-bedroom, 3-bath detached house measuring 2,338 square feet.

That’s what she got in Santa Cruz: a 2,751-square-foot, detached, single-family home with four bedrooms, two-and-a-half baths, and a two-car garage. In Palo Alto, that kind of house is indeed selling for over $2 million dollars. (Zillow suggests that it’s selling for the same price in Santa Cruz: the listing for the Downings’ new place said it was “$700-845k below active comparables.” Apparently they got a deal.)

The irony is that Downing disparages Palo Altans who, she says, want to maintain the city’s suburban character, while she’s chosen to move to a suburb and to a house whose Walkscore is a “car-dependent” 39 out of 100.

When a commenter on the Palo Alto Forward blog questioned her purchase of the Santa Cruz house, Downing dodged his question, too: “I’m making choices and trade-offs for my family, that I’m very privileged to be able to make,” she bristled. “The fact that we can afford to buy anything at all and that we have jobs that allow us flexibility is a giant privilege most working class people don’t have.”

Nobody is questioning Downing’s privilege. It’s the discrepancy between her stated and evident motives for leaving Palo Alto that rankles.

“Abusive” cities

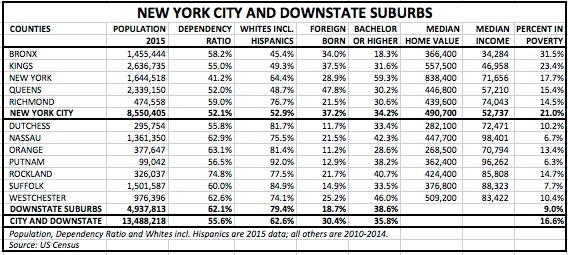

Downing’s disconnect aside, housing prices in Palo Alto really are insane. In July theaverage rent for a two-bedroom apartment was $3,806. The median home value is $2.486 million.

Downing blames the eye-popping prices on the city’s gross jobs-housing imbalance, which she in turn attributes to the council’s having approved tons of office development but not the housing for all the people who would be working in those offices. As of 2014, Palo Alto had almost three times as many jobs (95,460) as employed residents (31,165).

The upshot, she writes, is “the bizarre reverse commute in the Bay Area where more people live in San Francisco but work in Palo Alto or Mountain View.” In her view, the fault isn’t the companies that came to Silicon Valley.

[T]hey were invited with open arms. Part of the reason it happened that way is that in the 70s [sic] San Francisco created a stringent cap on office expansion, and it’s one of the reasons why it’s the Peninsula that became Silicon Valley and not the city of San Francisco until maybe the last 7 years or so. Companies went to where they were wanted. It’s the cities which are abusive because they take all that tax revenue from those companies but then don’t shoulder any of the burden of housing the people that work there—claiming…that other cities should bear that burden instead.

A good point (local jobs-housing imbalances stink)…

Yes, Silicon Valley cities have been encouraging massive development without permitting housing commensurate with the number of new workers.

The latest poster child for this sort of reckless behavior is not Palo Alto but rather the city of Santa Clara, which on June 29 approved Related Companies’ $6.5 billion, 9.7 million square-feet CityPlace project. To be built just north of Levi’s Stadium on 240 acres of city-owned land (a former landfill), CityPlace will include up to 5.7 million square feet of offices, 1.1 million square feet of retail, 700 hotel rooms, a 35-acre park, and up to a paltry 1,360 apartment units. It will create 25,000 new jobs.

As reported in the Silicon Valley Business Journal by Nathan Donato-Weinstein:

“This project, looking at the real estate side of it, and the fact that we own it, it’s whipped cream with a cherry on top,” said Mayor Lisa Gillmor prior to the vote. “Not only will we get the development that services our community, but also we’ll reap the financial benefits of having a cash flow into our general fund for generations to come.”

On July 29 San Jose, where housing far outnumbers jobs, sued Santa Clara over the project, alleging that the huge gap between the number of new jobs City would generate and the housing it would provide contradicted Santa Clara’s General Plan and would have profound and unnecessary environmental impacts in the region. Land use anarchy, anyone?

…and bad history (letting Stanford off the hook)

San Francisco voters passed the city’s office cap in the mid-80s, not the 70s, a good two decades after the Peninsula became Silicon Valley. And the impetus for the Peninsula’s transformation did not come just from local governments but from the ambitions of a giant private landowner and developer: Stanford University.

“Palo Alto city government,” Downing avers,

openly and decisively created and embraced the Stanford Research Park which now houses many of the biggest technology companies in the world (VMware, Tesla, SAP, HP, etc.) and more than 100,000 workers. Stanford Research Park LONG predates the likes of Google and Facebook and Page and Zuckerberg — it was created in 1951.The city had to re-zone that space and specifically entice tech companies to come there.

Palo Alto did not create the Stanford Research Park; Stanford did.

University of Washington history professor Margaret O’Mara tells the story in her fascinating 2005 book Cities of Knowledge: Cold War Science and the Search for the Next Silicon Valley. Originally called Stanford Industrial Park, the project was the postwar brainchild of Stanford administrators, notably Provost Frederick Terman and President Wallace Sterling. They remade their rich but undistinguished school into a scientific research powerhouse and a vehicle of regional economic development by leveraging federal R&D monies, shrewdly exploiting Stanford’s extraordinary land holdings, and capitalizing on the area’s beauty and fine climate and California’s booming militarized economy. It was Stanford that enticed high-tech companies to come to the park, and the park’s 1960 expansion “grew out of the demands of its tenants for more space.”

Nor, as Downing indicates, did the city of Palo Alto and its residents view Stanford’s development of its land with unconditional enthusiasm. Though encouraging high-tech industrial production was the major thrust of the university’s economic agenda, its to-do list also included building a mall, the Stanford Shopping Center. Palo Alto elected officials initially opposed the mall, fearing that it would drain revenue from the city’s downtown retail, and threatened “not to provide sewer service to the site.”

They soon dropped their opposition. “Palo Alto readily agreed to incoporate the land developments into the city, thereby providing Stanford with public utilities and road upkeep (and providing the city with tax revenues.” Stanford doesn’t pay taxes, but the companies at Stanford Research Park and the Stanford Shopping Center do. The city “made no further efforts to control the path of development.”

The city’s residents were not so easily pacified. When Stanford announced in 1960 that the Industrial Park would be expanded into the foothills, “neighborhood opposition…led to a fiercely fought ballot referendum campaign that President Sterling called ‘the Battle of the Hills.’” The university won that battle and proceeded with the expansion. In a public relations gesture, it replaced “Industrial” in the park’s name with “Research.”

What Stanford did not do is change its suburban model of land use.

A 1962 survey showed that the majority of the Park’s 10,500 employees did not live in the immediate area but commuted from communities south of Palo Alto (56 percent). Seven percent lived outside the ‘regional area’ of the Peninsula altogether. Palo Alto residents made up 21 percent of the workforce. Employees overwhelmingly depended on cars to get to work.

And, O’Mara writes, Stanford came to be regarded as a “model city,” a prototype for regional economic development around the world—and on the Peninsula.

[B]ecause of developments like the Industrial Park, the Peninsula was on the leading edge of the trend toward living in one suburb and working in another. The residential and commuting patterns seen in the Park in 1962 also presaged the later housing shortages that would face the Bay Area, particularly Palo Alto, where by the end of the twentieth century few professionals could find available and affordable places to live.

In a post-resignation-announcement interview, Stanford Political Journal reporter Andrew Granato asked Downing, “What do you see as Stanford’s role in housing politics, and do you think it can or should do anything?”

Downing equivocated, praising the university for “trying to add a certain amount of housing for its employees or students or faculty,” but subtly criticizing the school for not doing more:

I think that Stanford has always tried very hard to be a good neighbor to Palo Alto. They’ve tried to be very friendly and supportive….[A]t the same time, Stanford has been relatively quiet about what’s going on in Palo Alto and the Bay Area in general with respect to housing.

Far from being a good neighbor, Stanford has long been a major source of the jobs-housing imbalance that Downing deplores. Now, in its largest-ever off-campus expansion, the university is planning to build a $568 million office park that will accommodate 2,400 university employees on a 35-acre site in Redwood City. Stanford considered putting the project in Palo Alto but couldn’t find enough space.

To be sure, as per Downing’s argument, like Palo Alto, Redwood City has given Stanford a go-ahead. The university got it in 2013, when Redwood City approved Stanford’s plan for the property in return for more than $15 million in public benefits, including bike lanes, a business boot camp for Redwood City residents, a free speakers series from the Graduate School of Business, and a free shuttle for its employees and members of the public from the Redwood City Caltrain station to the offices. In keeping with Stanford’s suburban commuter model, the complex will include a gym with a pool, cafes and a small park—but no new housing.

“After the construction is completed,” wrote Chronicle reporter Wendy Lee, “Stanford is expected to become one of Redwood City’s largest employers.” Redwood City Economic Development Manager Catherine Ralston enthused: “ ‘It’s a really great opportunity for Redwood City. It’s going to bring a lots of jobs to the area.’”

Redwood City Councilmember Jeff Gee told Chronicle reporter Wendy Lee that a Stanford survey found only 8 percent of its employees living in or near Redwood City. “The Redwood City council considered and rejected allowing housing on the site,” wrote Lee, stoking some residents’ fears that an influx of Stanford employees would further inflate already high rents.

The Prop. 13 factor

Why do cities pursue jobs and not housing? One reason is that new housing, especially housing for families with school-age children, requires many more municipal services than commercial development.

Another is that Prop. 13 severely constrains property taxes by limiting annual increases to 2%; only when a parcel is sold or new construction occurs can a property’s value be re-assessed. The law favors parties that hold on to their property for a long time, above all big corporate landholders. It disproportionately burdens most homeowners, especially new ones, and new businesses. One study found that enacting a split-roll initiative that taxed corporations on the market value of their property would generate $8.2 to $10.2 billion in annual revenues for California.

Downing’s position is confusing. She stands with the Evolve campaign to maintain current Prop. 13 protections for all residential property, provide an exemption for small businesses, and establish a regular, yearly reassessment of all non-residential property in California. “Corporations used to pay the bulk of property taxes, she writes, “but now 75% are paid by residential properties, and places like Disney literally pay as much in property taxes as a reasonably sized single-family home.”

But she also embraces the argument that eliminating Prop.13 and allowing all property to be assessed every year would discourage Nimbyism and encourage development. As one of her correspondents on Medium, Eric Kingsburgy, wrote:

NIMBYism is able to take hold in places like Palo Alto because [in a system where property taxes don’t change,] more development provides absolutely no benefit to incumbent property owners….More people only means more traffic, busier parks, and more crowded schools….

A California without Proposition 13 would still face hurdles to development, and the abuse of land use regulations—no one likes crowded parks or traffic—but to a much lesser extent….Residential that bought $100,000 homes in Palo alto in the 1980s would have seen their property taxes skyrocket along with their property values, leaving them with two options: move to a lower cost area or push for measures that would make their property less valuable.

Downing responds: “Agree with everything you’ve written!” And then she refers “folks who are interested in Prop. 13 reform” to the Evolve campaign. Go figure.

The numbers game: how much of Palo Alto is zoned for single-family homes?

By contrast, when it comes to property values, the housing crisis, and zoning, Downing is unequivocal: the way to lower housing prices is to loosen zoning laws that restrict development by imposing “an artificial constraint on supply.”

Her reiterated example is Palo Alto’s zoning. “Only something like three percent of the city,” she told Brinklow, “is zoned for any sort of multi-family use. For most places it’s illegal to build a duplex.”

Brinklow asked Mayor Burt: “Is it true that 97 percent of the city is zoned R-1?”

Burt: “That is a misrepresentation.”

Correct. According to the city’s Comprehensive Plan, 4% of Palo Alto’s 26 square miles is zoned for multiple-family dwellings, and 25% is zoned for single-family dwellings. (Forty percent of the city is zoned for parks and preserves, another fifteen percent is dedicated to agriculture and other open space.)

But zoning doesn’t tell the entire story. The Plan also says that 38% of the housing stock is multiple-family units, and 62% is single-family. So single-family predominates, but not to the extent that Downing has implied.

Downing supported Jerry Brown’s anti-democratic giveaway to the real estate industry

In an interview with Los Angeles Times reporter Michael Hiltzik, Downing praised Jerry Brown’s controversial by-right housing legislation, Trailer Bill 707, declaring that it “does everything that needs to happen.”

It’s a curious endorsement, because one thing Brown’s proposal doesn’t, or more precisely, didn’t—since it just died in the Legislature—do is the thing that, Downing thinks, needs to happen: relax residential zoning standards in Palo Alto or anywhere else in California.

Trailer Bill 707 specified that if a project conformed to local zoning and contained 5-20% affordable housing, it would be permitted by right, meaning without any environmental or other public review. A draconian giveaway to the real estate industry, the measure was defeated by a statewide coalition of affordable housing advocates, environmentalists, and labor organizations.

Given her concern about the lack of civic engagement in Palo Alto—in her words: “there’s maybe one thousand people who pay attention to city government….A minority of wealthy homeowners can create a network to get candidates elected very easily”—you might think Downing would have been put off by Trailer Bill 707’s hostility to local democracy.

Instead, Downing shares that hostility. She favors a strong, centralized state. “Countries like Germany and Japan,” she writes,

do not make planning decisions at the local level. They make them at the national level….They do what’s best for all the people, not just the people in one small city[,] and they do what’s best for the country’s economy as a whole…

In good neoliberal fashion, she thinks planning is all about economics, and that what’s best for the economy is a state that vigorously intervenes in behalf of market freedom. At her last Planning Commission meeting, on July 27, she voted against raising the affordable housing development impact fee from $20.37 per square foot to $60, stating that the “massive and aggressive” increase would discourage the construction of affordable housing.

I’m guessing, then, that Brown’s bill appealed to Downing because it drastically curtailed local say in development, to the fulsome benefit of property capital. “Capitalism and property ownership,” she writes,

are enshrined in literally hundreds of thousands of laws on [sic] this country, including our constitution. For so long as the U.S. constitution still stands, this is the only system that we have and understanding its rules remains a critical element of making policy for the future.

Perhaps Downing skipped constitutional law class; the U.S. constitution says nothing about capitalism.

Given Downing’s outrage at the “astronomical” cost of housing in Palo Alto’s and her professed solicitude for “the average Joe,” you might also think that she would have deplored a bill that greased the permit process for projects with as much as 95% market-rate housing.

Market-rate housing, however, is all that Downing wants to see built. Responding on Medium to a correspondent who doubted the superiority of “national zoning decision-making” and “centrally created affordable housing,” Downing wrote:

I’m only talking about lifting zoning restrictions so that more market-rate housing is legally allowed to be built in the city. So I’m most definitely not talking about “centrally created affordable housing.” My goal and belief is that housing growth (market-rate) must keep up with job growth.

She points to “places like Texas which have far fewer zoning restrictions (none at all in Houston).”

[E]ven though they’re experiencing an unprecedented population boom, their prices aren’t soaring like California’s. And it’s because they have something much closer to a free market where people can supply enough housing to actually meet demand.

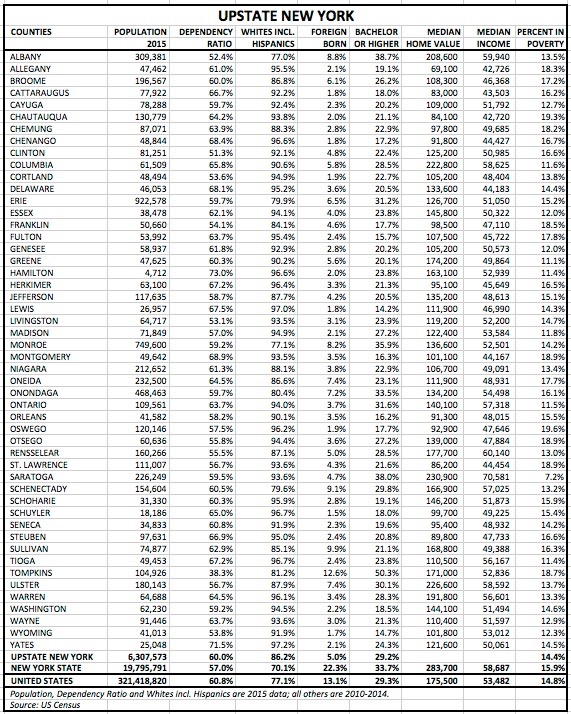

Ahem. Prices in Texas, including Houston, have been soaring—not to the Bay Area’s catastrophic levels, but soaring (50% leap in 2010-15) nonetheless.

But let’s talk about California, and specifically our region. Here the textbook theory of supply-and-demand—prices fall as supply increases—doesn’t apply. As I wrote in 48 hills last December:

What’s making home prices soar in our region is the simultaneous incursion of hundreds of thousands of highly-paid tech workers and a flood of foreign investment. In June the Contra Costa Times reported that “[h]igh-tech employees make a yearly average of $124,000 in Santa Clara County, $107,000 in the San Francisco-San Mateo area, and $101,000 in the East Bay.” By contrast, wrote George Avalos, tech workers nationwide average about $84,000 a year. “This is a very, very hot area to live and work,” [demographer] Steve Levy told Avalos, “and the wage growth is pushing up housing prices.”

(Levy, by the way, sits on the board of Downing’s Palo Alto Forward.)

Downing presumably thinks that if enough market-rate housing were produced, housing prices would fall to affordable levels. I always like to ask someone who holds that view: how much housing would it take? So far, the answer has been: I don’t really know. That’s what former Trulia Chief Economist Jed Kolko told me. Ditto for George Mason University Law Professor Ilya Somin, who wrote a Washington Post op-edpraising Downing’s attack on “restrictive land use regulations.” I bet Downing has no idea, either.

In her case, further questions seem to be in order: how much and what kind of new housing would it take to lower the price of four-bedroom, two-plus bath single-family homes in Palo Alto from $2.6 to $1.55 million dollars?

The Palantirization of downtown Palo Alto

In Palo Alto, the tech tsunami hasn’t just driven up housing prices; it’s also decimated the city’s retail sector, which has been colonized by tech offices. Things got so bad that in May 2015 the council passed a 45-day urgency interim ordinance that prohibited the conversion of existing ground-floor retail to offices. A month later it extended the ban to April 30, 2017.

As an employee of Peter Thiel’s Palantir Technologies who works in downtown Palo Alto, Downing’s husband Steven is implicated in the tech displacement of the city’s retail businesses.

Palantir, wrote San Jose Mercury reporter Marisa Kendall in April, is “taking over” downtown Palo Alto. The secretive company rents at least nineteen properties comprising 250,000 square feet, or about 12 percent of all downtown’s commercial space downtown. Office rents have climbed accordingly. Now tech start-ups are having a hard time finding space that they can afford.

Can a city have too many (tech) jobs?

To Downing, only a maniac would entertain this question. Responding on Medium to an unnamed correspondent who apparently asked whether Palo Alto would try to shed some tech businesses, Downing wrote:

I don’t think Palo Alto is going to choose to get rid of the companies. If they do, their tax base will shrivel and they’ll have a hard time paying city employees and paying off all the pensions they’re already obligated to fulfill…

And…what kind of insanity is it to be trying to kill high paying jobs and forcing companies out of town when the rest of America is bending over backwards trying to attract those companies?….Everyone else in the world is looking at Palo Alto and scratching their heads at the thought of a city that thinks its grand solution is to slaughter the golden goose.

Actually, the golden goose metaphor doesn’t work for the tech industry in the Bay Area today. As depicted by Aesop and other fabulists, that bird was killed by the greed of its owners, who forced it to lay more than its customary single egg a day.

A better analogy is Audrey II, the man-and-woman-eating plant in film The Little Shop of Horrors, whose exponential growth drew customers to the shop but whose insatiable appetite threatened to destroy everything around it. When its owner, the unprepossessing Seymour, realizes that it cannot be appeased or controlled—indeed, that it’s about to eat him—he kills it.

Like all metaphors, this one has its limitations. Unlike Audrey II (but like zoning), the tech industry is a human artifact and thus susceptible to human control. Accordingly, some Palo Altans are contemplating additional curbs on tech’s growth in their city—for example, Mayor Burt.

“Palo Alto’s greatest problem right now,” the mayor told Brinklow,

is the Bay Area’s massive job growth. Cities are still embracing huge commercial development with millions of square feet of office space they can’t support….[W]e have to do away with this notion that Silicon Valley must capture every job available to it….We’re looking to increase the rate of housing growth, but decrease the rate of job growth.

Brinklow was incredulous: “You want fewer jobs?” [italics in original]

Burt: “I know, it’s a strange idea to contend with. But this doesn’t mean we want no job growth….We want metered job growth and metered housing growth, in places where it will have the least impact on things like our transit infrastructure.”

For a city official to espouse less job growth in his town is beyond strange; it’s unheard-of. As a challenge to the prevailing growth ideology, it’s on par with 48 hills editor Tim Redmond’s recent piece welcoming the drop in San Francisco land values that, according to the city’s Controller, would result from requiring twenty percent of the units in new apartment buildings to be below-market-rate. But you expect such radical pronouncements from Redmond, not from a mayor, especially the mayor of a Silicon Valley city who’s a tech executive to boot.

Burt’s stated goal is to accommodate some growth and still maintain Palo Alto’s distinctive character. That means going slow, because, he contends, the rate of the region’s job growth

is just not sustainable, if we’re going to keep [Palo Alto] similar to what it’s been historically. Of course we know that the community is going to evolve. But we don’t want it to be a radical departure….[W]e balance things….[W]e’re looking at increasing our developer fees and investing more in affordable housing. We have 2,500 units of BMR [below-market-rate] housing over the last decades, and a lot of hard work went into that.

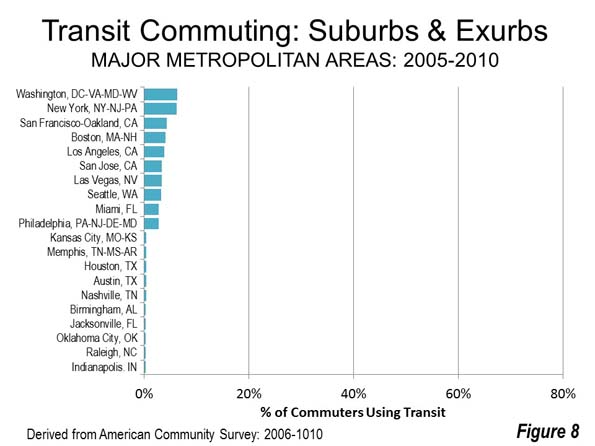

Improving transit, said Burt, is key: “The community would be more willing to embrace new development, even commercial development, if we could solve the transit problem….[J]ust in the last year, for the first time ever, I’ve become really confident that things will get better.”

Brinklow: “Why?”

Burt: “The single biggest thing is probably electrifying Caltrain.” He’s also encouraged by the extension of BART to San Jose, Palo Alto’s rideshare app, Scoop; the Palo Alto Transportation Management Association; and the advent of “shared, autonomous vehicles powered by carbon-free electricity.”

The real culprit: baby boomers “aging in place”

To Downing, Burt epitomizes the chief culprit in the affordability crisis—not the “middle-aged, jet-setting executives and investors” named in her resignation letter but rather “older homeowners,” boomers who got into the housing market when the middle class could still buy a house in Palo Alto, and who are now, in her indelicate phrase, “aging in place.” She attributes their slow- or in her view, no-growth agenda—“they just plain don’t want to see more people in the city”—to two motives: maintaining or, better yet, increasing the values of their property; and preserving Palo Alto’s suburban character.

What’s worse, she says, they’re elitist hypocrites. When Brinklow noted that the slow-growthers argue that the city’s transit infrastructure and water use should be limiting factors in development, Downing interjected:

The exact same people who complain about infill housing will show up to complain when you want to expand transit….These people will say anything, but they don’t really care about congestion or water use. They care about keeping the town looking exactly the way it is….They think public transit is for the poor and apartments are for people on welfare.

Brinklow: “You allege that all of these policy objections are just a cover for a personal agenda?”

Downing: “Well, we know that.”

Slow growth vs. smart growth

I emailed Cheryl Lilienstein, the president of Palo Altans for Sensible Zoning, and another “older homeowner,” asking if her group opposed expanding transit in town. Lilienstein replied that it depended on the kind of transit.

“For years and years,” Lilienstein emailed, “we’ve been asking for cross-town shuttles to take us to schools, large job centers, hospitals, and community services nowhere near El Camino.”

Regarding high-density development around mass transit—for example, at the Caltrain stations, being pushed by Palo Alto Forward, the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA), the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, and ABAG—she wrote:

We oppose it. VERY few residents now living in high density housing near transit use it. They live there because they want to live in Palo Alto, and they still use cars to get where they need to go, so it’s unrealistic to assert new high density development will be car-free. It won’t.

By common consent, traffic congestion in Palo Alto is horrendous, due to the huge number of commuters driving into town. The question is, what to do about it? The issue is front and center in the current public process to update the Comprehensive Plan.

PASZ’s basic position, set forth in its comments on the Draft EIR for the update, is that before increasing population, the city needs to do what it can to decrease traffic and the associated air pollution in accordance with “a set goal.” Only then, should the city “proceed with a slow housing program that prioritizes housing for those whose presence would provide diversity for an economy that serves all residents”—specifically:

- People who under present conditions will never be able to buy here, typically defined as the middle class: clerical workers, city staff, middle management, tradespeople, low income workers, service workers, small business owners

- Seniors living here who don’t own their houses or still have mortgages and want to retire

- The homeless

TKPASZ wants to maintain Palo Alto’s suburban character and still build housing that’s affordable to low-income people. From their Platform:

Reduce the maximum development volume in certain zoning districts so that when state-mandated density bonuses are applied, the resulting volume matches what current zoning maximums would allow. In other words, state density bonuses for low income housing should not be used to produce buildings that are massive and out of scale with the surrounding neighborhoods.

….

Development should be compatible with existing neighborhoods and take into account school impacts.

I also asked Lilienstein what she thought of the transportation innovations that give the mayor hope.

Burt,” she replied, ‘is overly confident, in my view, yet I wish his vision was possible.” Her top priority is “increas[ing] ease of movement INSIDE the city.” To that end, she wrote,

I don’t see how electrifying CalTrain and increasing the ridership (both are good things) will do anything but increase crosstown gridlock for Palo Alto, since there is no grade separation” for the train tracks. The single greatest transformative investment would be to trench the tracks so there can be an increase in cross-town flow. Without, even the future promised technology improvements will be insignificant.

If BART is ever extended to San Jose, down the east side of the bay, how would that help us? The Transportation Management Association might put a dent in the traffic problem, but it’s basically underfunded and complicated/expensive to enforce. Scoop is a good idea, a good use of public money, but do Palo Alto worker actually use it?

Downing, by contrast, thinks that “adding housing…is going to relieve a lot of the congestion we’re seeing” by allowing people “to live in the same community where they work. If you look at the people who actually live and work in Palo Alto,” she told Brinklow, “a substantial number…are walking or biking to work, so they’re not part of the traffic.” Now most of the in-commuters live far away.

Palo Alto Forward’s website lists “five common-sense reforms that could remove barriers to housing”:

- Encourage studio apartments and smaller units

- Encourage residential units over ground-floor retail

- Make it easier for homeowners to build second units

- Allow car-light and car-free housing in walkable areas near transit

- Facilitate new senior housing, including alternative models

The underlying assumption is that growth is essential to economic health and hence must be accommodated. From its platform:

On its current course, Palo Alto will continue to experience traffic and parking issues from denser uses of existing buildings, but it will have turned away new businesses and new workers who no longer have appropriate housing. The very economic growth that makes Silicon Valley a gem in America’s economic crown will slowly be chipped away, hurting local businesses, school funding, and employment rates alike.

Dancing around the growth issue

What the PAF platform never quite makes clear is whether the group can thinks the city should seek to accommodate as much growth as possible.

Brinklow asked Downing: “What about people who argue that a city like Palo Alto just can’t ever build enough housing to really satisfy demand?”

Downing: “I think it’s a misconception that you can never build up to demand. We have a pretty good idea what demand is: Every day, the effective population of the city [66,000] doubles from the number of people who come in just for work. That tells us something about how much housing we need. It’s not infinite.”

But elsewhere, she indicates that growth per se is advantageous. A member of the Bloomberg News team asked her if she thought “it’s fair for a community to collectively say, we don’t want to get any bigger, we don’t want to increase our population, we don’t want to live in a more dense area.” She replied: not if it’s a job hub. “As for these companies getting big,” she wrote in one of her Medium posts,

—that’s something to celebrate and be happy about, not to lament. It means you live in a prosperous area with lots of high paying jobs and that your city is getting tons of tax revenue to support the sort of services and programs residents want to see. The response is to build out the necessary infrastructure to make sure your city can handle the growth and plan thoughtfully about how to grow in a way that will be beautiful and convenient. The response isn’t to murder the golden goose which is making your city so desirable in the first place.

One of the qualities that made Palo Alto so “desirable in the first place” to the tech industry was the very thing that Downing would readily dispose of: the town’s suburban character. Paradoxically, that character is now jeopardized by the industry’s rampant growth. For Downing, however, nurturing that growth is paramount. Constraining it, she says, will lead to the decline of Silicon Valley.

“[I]f [what Palo Alto is doing],” she tells Granato,

continues this way, eventually we really are going to drive businesses and young people away. I mean it’s driving me away, right? And at that point, the locus of organization and development is going to shift; it’s going to go somewhere else. And I think that will be an extraordinarily painful thing for Stanford. It means less opportunities for its students, it means less collaboration between businesses and professors. I don’t think Stanford wants to be in a place that used to be the innovation capital of the world, but that’s kind of where we’re headed.

Forbidden questions

I’m no fan of Kate Vershov Downing—that’s been clear since the start of this story. I confess, however, that until recently, I shared Downing’s view that cities should strive to house the people who work in the businesses within their city limits, and that those who don’t should be judged harshly. Downing calls Palo Alto and other tech towns with jumbo job-housing imbalances “abusive,” referring to their unwillingness to house their tech workers. To me, the abusiveness involved dumping their housing and traffic issues on other cities—the sight of a “Google bus” parked in a Muni bus stop makes me scowl—and clogging the roads with long-distance commuters: when I left Palo Alto at 4 p.m. one afternoon last February, it took me two and a half hours to reach my north Berkeley home in my car, lurching forward in stop-and-go traffic all the way.

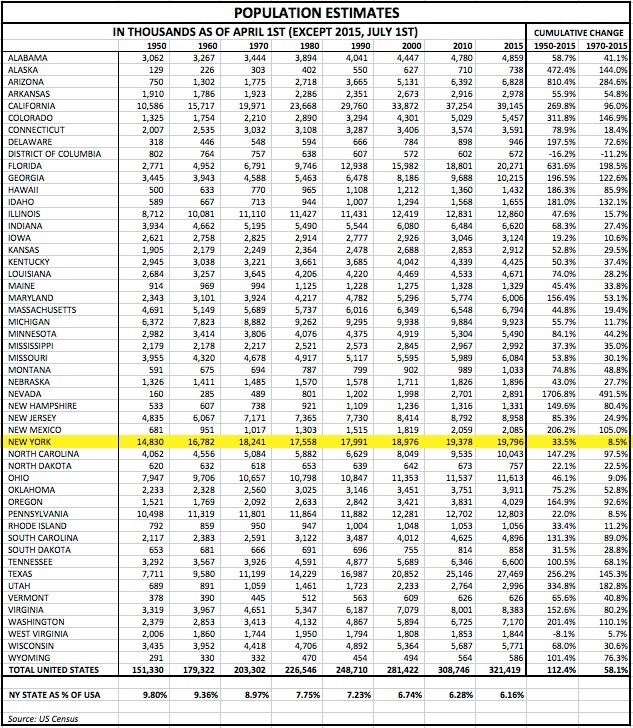

Contemplating the fight over growth in Palo Alto has made me rethink my position. Pace Downing, the Bay Area’s tech sector seeks infinite expansion. A report released by the Silicon Valley Competitiveness and Innovation project last February found that for the first time since 2011, more residents—7,600—left Silicon Valley for other parts of the U.S.—Seattle, Austin, southern California—than arrived from other parts of the country. The area still had a positive net migration, but many of the new arrivals came from abroad. The American-born workers are headed to places where the cost of living is lower; the competition for jobs, space, and venture capital less intense; single-family homes more affordable; and traffic less daunting.

In the report’s introduction, the sponsors of the project, the Silicon Valley Leadership Group and the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, called these numbers “warning signs” that “skyrocketing housing costs and increasing traffic congestion are eroding our quality of life” and making it hard to draw and retain sought-after employees.

In response, the SVLG and the SVCF lay out much the same agenda as Kate Downing: sustain the local tech industry’s warp-speed job growth by building a commensurate amount of housing and expanding the region’s transit infrastructure accordingly. Just so, SVLG supported Brown’s by-right housing bill, though, in a move that I suspect Downing, with her opposition to “centrally controlled affordable housing,” would criticize, it also cheered the California Supreme Court’s decision that upheld San Jose’s inclusionary housing ordinance.

Concentrated power undermines democracy. I’m talking about the economy, of course. Right now about a fifth of total jobs in the region—746,100—are in tech. The Bay Area’s appalling income inequality and its associated housing affordability crisis exist not in spite of but largely because of the high-rolling tech cataclysm.

But democracy entails more than economic equality; it also involves political freedom. Money talks, and these days tech oligarchs are speaking much too loudly in our public life—think, for starters, Ron Conway and Airbnb.

This quest for endless growth needs to be put on hold and replaced with a debate over the region’s carrying capacity and relevant public policy. How many jobs and people can the Bay Area support without further degrading the region’s quality of life, its cities’ distinctive characters, and the stability of their neighborhoods? Is it worth sacrificing these things for the sake of competitiveness? Who really benefits from the competitiveness race? Should a city’s receipt of a company’s taxes obligate that city to approve housing for the company’s workers? Do people have a right to live wherever they want? Barring prospective residents from your town on the basis of race or ethnicity or gender is wrong—and illegal. What about setting a limit on density or the size of a city’s population? And where’s the proof that people living in dense, transit-oriented development drive significantly less?

For the region as a whole, the best thing that could come out of the Downing imbroglio is the expansion of the debate that’s roiling Palo Alto—not just to every city hall, but to every state and regional planning agency and legislative body. One point of universal agreement is that neither Palo Alto nor any other city can resolve the jobs-housing conundrum on its own. But today the growth ideology reigns supreme; no questions allowed. As long as that’s the case, the conundrum will persist and worsen.

This piece originally appeared at 48hills.org.

Zelda Bronstein, a journalist and a former chair of the Berkeley Planning Commission, writes about politics and culture in the Bay Area and beyond.

For ongoing, in-depth coverage of Palo Alto’s land-use politics, see the reporting of Gennady Sheyner in the city’s alternative newspaper, the Palo Alto Weekly.