New research supports the conclusion that anti-sprawl policy (urban containment policy) is incompatible with housing affordability. Build-zoom.com economist Issi Romem finds that: “Cities that have curbed their expansion have – with limited exception – failed to compensate with densification. As a result they have produced far less housing than they would otherwise, with severe national implications for housing affordability, geographic mobility and access to opportunity, all of which are keenly felt today as we approach the top of housing cycle.”

Romem had previously produced stunningly innovative research, estimating the extent of urbanization in US cities every decade from 1940 to 2010. He provides maps that show the changing urban expanses in each census. Romem uses the larger metropolitan areas, the currently defined Combined Statistical Areas (CSAs). This combines metropolitan areas that are adjacent and significantly economically connected, such as San Francisco and San Jose, New York , southeastern Connecticut and Allentown, and Los Angeles and Riverside-San Bernardino.

The new research is a similarly important addition to urban policy. Like most in urban planners, Romem strongly believes that the "ills of the urban sprawl must be curbed." However, importantly, Romem’s research is driven by data, rather than urban planning principles often disconnected from the aspirations of households. This article examines Romem’s most recent research in the context of middle-income housing affordability.

Middle-Income Housing Affordability

Housing affordability is much broader than “affordable housing” for lower income households. In markets regulated by urban containment, middle-income housing usually becomes too expensive for many middle-income households. In such markets, there is considerable discussion of housing affordability, but little that gets to the heart of the matter.

Housing affordability is appropriately compared both between housing markets and within markets over time. Perhaps the most effective tools are price-to-income ratios, such as the median multiple (median house price divided by median household income) used in the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey. Now in its 12th edition, the Survey shows virtually all major metropolitan areas with seriously unaffordable housing to have urban containment policy.

Development Limits: More Politics than Mountains or Water

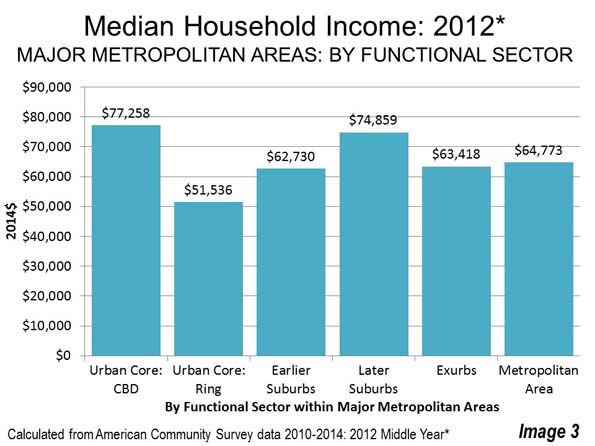

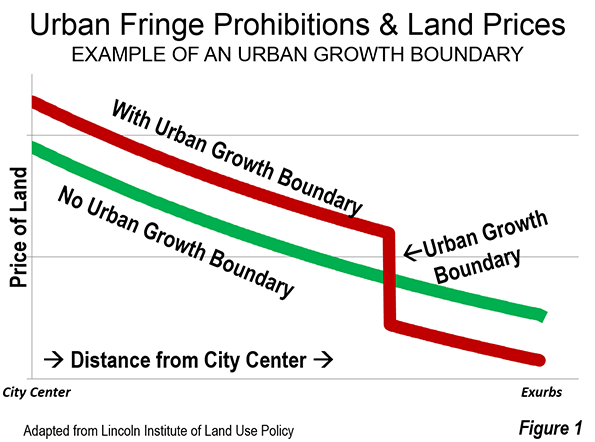

In covering Romem’s research, Richard Florida acknowledges describes the crucial role of role of land markets in maintaining housing affordability. Of course, housing affordability is a casualty of urban containment policy because it destroys the competitive market for land on the urban fringe. As a result house prices rise substantially relative to incomes (Figure 1).

Romem and Florida, to their credit, have proposed means they think can preserve housing affordability within a framework of urban containment, such as by land use regulation that permits higher densities, including redevelopment of lower density areas. While wishing them luck, there is little cause for optimism. Near 50 years ago, legendary urbanologist Sir Peter Hall suggested that “soaring land prices …. certainly represent the biggest single failure of the system of planning introduced with the 1947 [Town and Country Planning] Act” (see: The Costs of Smart Growth Revisited: A 40 Year Perspective). Urban containment policy, the principal strategy of forced densification, cannot repeal the law of supply and demand. Seventy years of experience prove that.

Florida and others have noted the challenges of cities running up against their development limits. However, in the United States, only the artificial political limits of regulation have been approached, rather than the natural barriers of topography or geography (see: A Question of Values: Middle-Income Housing Affordability and Urban Containment Policy). Where a binding urban growth boundary is imposed between the city and an impassible mountain range, the scarcity induced price increases result from the boundary, not the mountain.

Politics, Topography & Geography in the San Francisco Bay Area

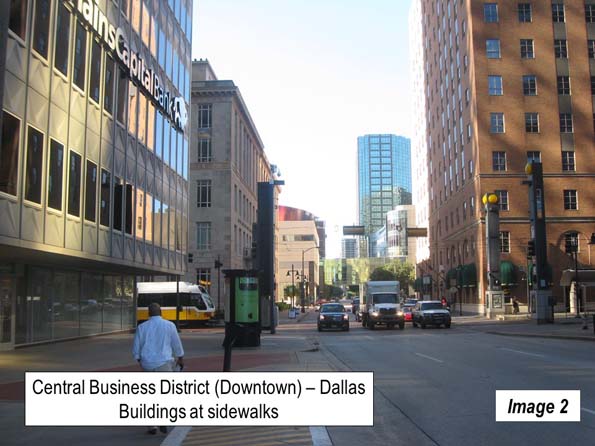

Take, for example, the San Francisco Bay Area, which has often been cited as a place where natural barriers have left little land for development. This is an impression easily obtained observing the fairly narrow strips of urbanization on both sides of San Francisco Bay, hemmed in by hills.

However the Bay Area’s urbanization long ago leapt over the most important water bodies and then the Berkeley Hills to the east. Not only is the San Francisco Bay Area CSA high density, but it is also spatially small. In 2016, the San Francisco built-up urban area was only the 23rd largest in land area in the world. New York, the world’s largest built-up urban area in geographical expanse is more than four times as large.

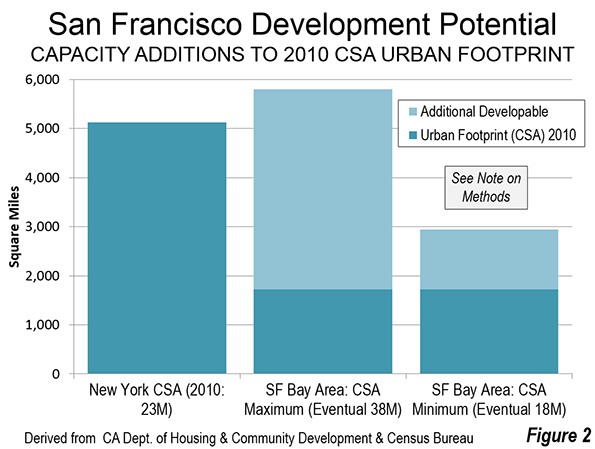

There is plenty of developable land in the San Francisco Bay Area. Data in a 1997 state analysis indicated that another 1,500 to 4,300 square miles (3,900 to 11,000 square kilometers) could be developed in the Bay Area CSA. The lower bound assumed no farmland conversion and stringent environmental regulation. The report also found that in recent years, residential development had become marginally denser, yet not incompatible with the detached housing remains the preference in California (Figure 2). The state has more than enough developable land for future housing needs.

Updating the data to account for the development that occurred through 2010, the developable land supply could support an urbanization of between 18 million and 37 million population, well above the 2010 urban population (Note on Method). At the most, there is capacity to accommodate the population of Tokyo – Yokohama, the world’s largest urban area. At a minimum, use of the available land would catapult the Bay Area CSA ahead of the Los Angeles-Riverside CSA, more than double its present population.

Of course, the Bay Area is simply not growing fast enough to reach even the lower population figure any time soon. Even with its slower growth, however, the competitive market for land no longer works, in large measure because of land use regulation. The San Jose metropolitan area has the fourth worst housing affordability in the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey and the San Francisco metropolitan area is 7th worst (both metropolitan areas are in the CSA).

The decades old Bay Area housing affordability crisis, and that of other metropolitan areas seeking to force higher densities, is more the result of policy than nature.

Urban Containment: Negative Externalities

Moreover, planning authoritarianism cannot tell everyone where and how to live. For many, high density apartments (owned or rented) are not a substitute for the detached house. Indeed the substitute for the detached housing the Bay Area for many is often a detached house in Nashville or Kansas City or any of many other major metropolitan areas where housing is much less expensive. Last year’s (2014) IRS migration data shows that California is losing both younger households and middle income households.

Higher than necessary house prices are, of course, an even greater problem for low-income households, who not only are excluded from homeownership but most pay unaffordable rents. The latest data shows that California again has the worst housing cost adjusted poverty rate among the 50 states. Even Mississippi, with its reputation for poverty, cannot compete with that.

Romem expressed concern to The Wall Street Journal: “What you’ll get there is an exacerbation of the problems we already have in expensive cities. The distinction between homeowners and renters will become less and less a stage of life and more and more if your parents can help you.”

The Economist came to a similar conclusion: “Suburbs rarely cease growing of their own accord. The only reliable way to stop them, it turns out, is to stop them forcefully. But the consequences of doing that are severe" (See: Cities: Better for the Great Suburbanization).

Note on Method: Some of the CSA urban population is not in the continuous urbanization of San Francisco-San Jose built-up urban area, such as in the Santa Rosa, Stockton and Santa Cruz urban areas. This analysis is based on data from the California Department of Housing and Community Development and the U.S. Census Bureau. It is based on an estimate of additional development occurring from 1996 to 2010 and the land remaining after deduction of recently developed land. The population capacity assumes the “marginally higher” densities used by the California Department of Housing and Community Development, which it notes would not require substantial changes in the “current form of housing development” (1997).

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: San Mateo County on the San Francisco Peninsula (by author)