Probably no city in the high income world evokes impressions of urban decline more than Detroit — and for good reason. The core city of Detroit has lost more of its population than any developed world city of more than 500,000 since 1950. The city’s population peaked at 1,850,000 residents in 1950 and at its decline rate since 2010 could drop below 650,000 residents by 2020 census.

It was not always this way. During the first half of the 20th century Detroit was one of the fastest-growing core cities in the United States. Among the 20 largest core cities in 1950, only Los Angeles grew faster, percentage wise, than Detroit. The city of Los Angeles grew from 102,000 in 1900 to 1,970,000 in 1950. The city of Detroit almost matched that, growing from 286,000 to 1,850,000.

The city’s nearly 1.6 million population increase exceeded that of all other US municipalities except Los Angeles, Chicago and New York, which grew at an unprecedented pace over the period, adding more than 4.5 million residents.

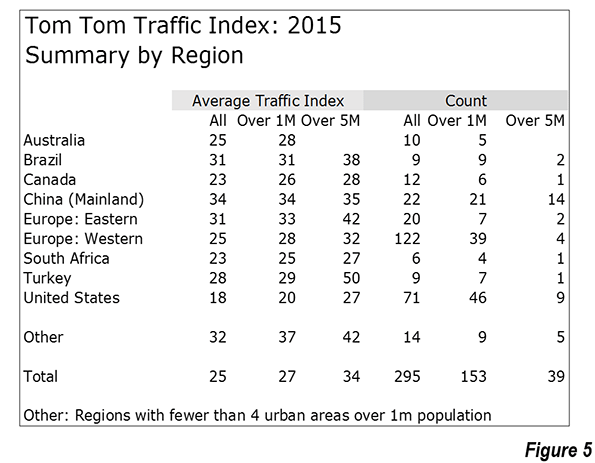

The current defined area of the Detroit metropolitan area grew by 1950 to nearly 6 times its 1900 population, to 3,170,000 from 530,000. The growth of the metropolitan area from 1900 to 1940 closely tracked that of the fast growing Los Angeles metropolitan area, which widened its lead substantially through the end of the century (Figure 1). The Los Angeles area, which was only slightly larger than the Detroit area in 1940 reached a population of more than three times that of Detroit by 2010

The city of Detroit began to lose population after 1950. It lost 180,000 people between 1950 and 1960 and approximately 155,000 between 1960 and 1970. The 1970s were a particularly bad time for the many large core cities, and Detroit lost more than 300,000 people, or 20% of its population by 1980. But if Detroit was exceptional, it was not alone; virtually all large US core cities that did not annex territory between 1950 and 1980 lost population.

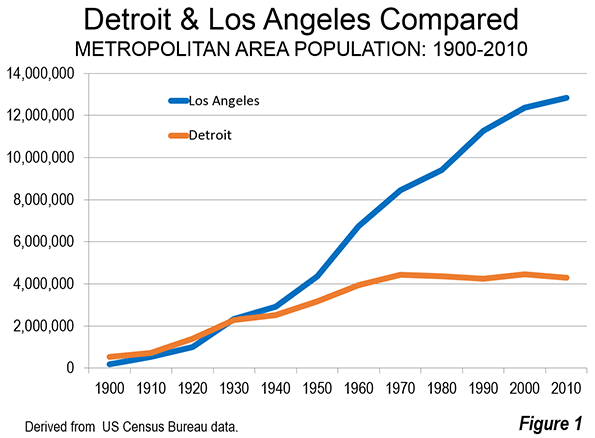

In fact, Detroit’s loss was not even the worst. During the 1970s, the city of St. Louis lost 27% of its population, dropping to little more than half its 1950 size, from 857,000 to 452,000. At this point and through 2010, St. Louis had the less than enviable record of the largest population loss for a major high income world municipality. As of 2010, the city of St. Louis had lost 62.8% of its population, more than the city of Detroit’s 61.6% (Figure 2).

But things were about to change. Between 2010 and 2015 the decline rate in both cities was moderated. But city of Detroit’s loss was large enough to wrest away the title for the largest decline from the city of St. Louis. According to the US Census Bureau’s 2015 estimates, Detroit has lost 63.3% of its population since 1950 while St. Louis lost somewhat less, at 63.1%.

Having spent considerable time in both cities, however, one does not get the same sense of urban devastation in St. Louis as in Detroit. The urban decline of city of St. Louis has been far more graceful than the city of Detroit. A long-time Detroit and St. Louis resident and commentator writing in the St. Louis Beaconcalled the differences “quite striking,” noting that Detroit’s devastation was far wider spread and that neighborhoods continue to thrive in large parts of the city of St. Louis.

Obviously, Detroit has faced huge challenges and probably greater challenges than St. Louis or the Rust Belt cities of Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Buffalo. Indeed, one of Pittsburgh’s strengths is its strong civic community downtown, with its large banks, its still strong neighborhoods and striking physical location. One of Detroit’s banks moved its headquarters to Dallas.

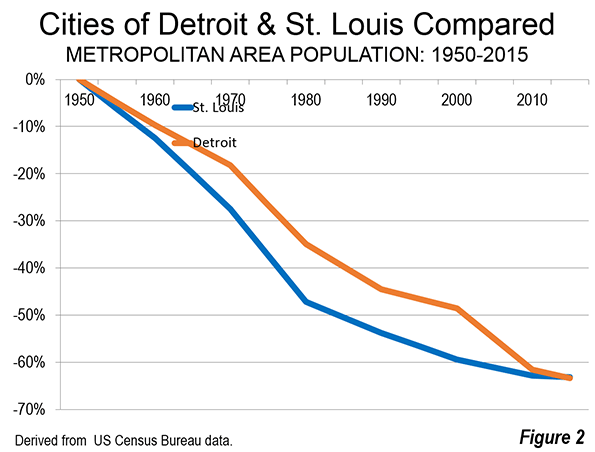

Figure 3 graphically illustrates the population trends in the Detroit metropolitan area since 1950. The city of Detroit’s massive loss is indicated by the first bar for each year. But despite the city’s losses between 1950 and 1970, totaling more than 340,000 residents, the balance of Wayne county (of which Detroit is the county seat) nearly doubled in population, from 585,000 to 1,150,000. However, since that time, suburban Wayne County (outside the city of Detroit) has stagnated downward to 1,088,000 residents (Figure 3).

The other suburban counties have done far better. The largest of these are Oakland County to the northwest of the city and Macomb County, which is straight north from downtown. Since 1950, Oakland County has grown from 400,000 residents to nearly 1.25 million in 2015. Macomb County, famous for the “Reagan Democrat” blue-collar worker vote, grew from 190,000 in 1950 to 860,000 in 2015. The smaller counties of Lapeer, Livingston and St. Clair also expanded strongly. Overall, the suburbs outside Wayne County grew by 240%, from 735,000 in 1950 to more than 2.5 million in 2015.

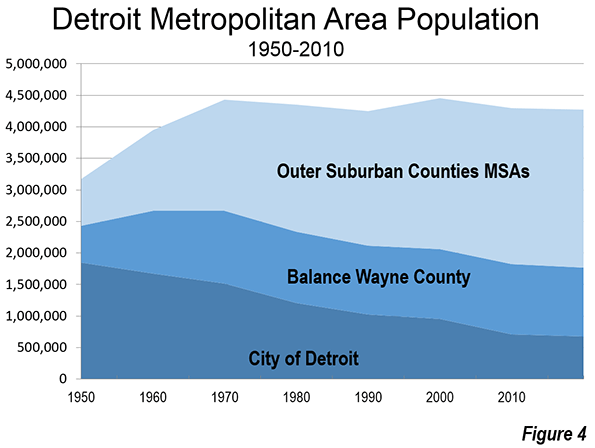

Early on, the metropolitan area continued to add people strongly. Between 1950 and 1970, the metropolitan population rose by 40%, to more than 4.3 million. The population dropped in both the 1980 and 1990 censuses. But in 2000, a new peak of 4.45 million was reached. The metropolitan area losses resumed with lower figures indicated for the 2010 census and in the 2015 estimates (4.275 million). The "ups and downs" of the metropolitan population are illustrated in Figure 4.

Given my own experience, the decline of Detroit is particularly surprising. As a consultant to Oakland County Executive Daniel T. Murphy between 1985 and 1990, I had the pleasure of witnessing firsthand cooperative efforts between the suburban leadership and the city of Detroit (under then Mayor Coleman Young) on transportation issues. Murphy and Young had established a regional cooperative process referred to as the "Big Four" along with Wayne County Executive Bill Lucas and then Wayne County Executive Edward H McNamara (and current Detroit mayor Mike Duggan, who was Deputy County Executive), along with the leadership of the Macomb County Commission. It was clear to me that there was a very real commitment on the part of all four to deal with the pressing problems of the area.

The good news is that there are signs of a turnaround in Detroit. I doubt we will ever see Detroit return to a its peak population of 1.85 million or even 1 million. Even the lower figure would require a reversal unprecedented in developed world urban history, made far more unlikely by the slow population growth of the Upper Midwest and laggard fertility rates nationally. (Note). But, for the first time in decades, there are signs of hope out of the city and its leadership. Good luck, city of Detroit and Mayor Duggan.

Note: See Wendell Cox, “International Shrinking Cities, Analysis, Classification and Prospects,” in Harry W. Richardson and Chang Woon Nam, Shrinking Cities: A Global Perspective, Routledge, 2014.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international pubilc policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: downtown Detroit