Black lives matter, we’re told—but in many American cities, black residents are either scarce or dwindling in number, chased away by misguided progressive policies that hinder working- and middle-class people. Such policies more severely affect blacks than whites because blacks start from further behind economically. Black median household income is only $35,481 per year, compared with $57,355 for whites. The wealth gap is even wider, with median black household wealth at only $7,133, compared with $111,146 for whites, according to a study by Demos and the Institute on Assets and Social Policy.

How, then, are cities faring in meeting the aspirations of their black residents, judged especially by the ultimate barometer: whether blacks choose to move to these cities, or stay in them? Among major American cities, three main typologies emerge: the high-flying progressive enclaves of the West, the historically large cities of the Northeast and the Midwest, and the fast-growing boomtowns of the South. Though results vary to some extent, the broad trend is clear: the most progressive-minded cities are either seeing a significant exodus of blacks or, never having had substantial black populations, are failing to attract them. These same cities, home to some of the loudest voices alleging conservative insensitivity to blacks, are failing to provide economic environments where blacks can prosper.

In theory, prosperous, growing western cities—the San Francisco Bay Area, Portland, Seattle, and Denver—should find it easier to provide upward mobility, as they have fewer disadvantaged people. Far from the South and not part of the Rust Belt industrial complex, they attracted far fewer blacks during the twentieth century’s Great Migration, when millions of blacks moved north. As a result, their black populations are small, compared with those of eastern cities—just 5.6 percent in the city of Portland, for example, compared with 53.4 percent in Cleveland and 46.9 percent in St. Louis. And many western cities are driving their small number of black residents out.

Portland is part of the fifth-whitest major metropolitan area in America. Almost 75 percent of the region is white, and it has the third-lowest percentage of blacks, at only 3.1 percent. (America as a whole is 13.2 percent black.) Portland proper is often portrayed as a boomtown, but the city’s tiny (and shrinking) black population doesn’t seem to think so. The city has lost more than 11.5 percent of its black residents in just four years. Metro Portland’s black population share grew by 0.3 percentage points from 2000, but that trailed the nation’s 0.5 percentage-point growth. This implies that some of Portland’s blacks are being displaced from the transit- and amenity-rich city to the suburbs that progressives themselves insist are inferior.

The San Francisco Bay metro area has lost black residents since 2000, though recent estimates suggest that it may have halted the exodus since 2010. The Los Angeles metro area, too, has fewer black residents today than in 2000. The performance in the central cities is even worse. America’s most liberal city, San Francisco, is only 5.4 percent black, and the rate is falling. It’s a similar tale in Seattle—“one of the most progressive cities in the United States,” as a Black Lives Matter protester noted. One city bucking the western trend is Denver. Though the Rocky Mountain city has a small black population—6.1 percent in the region and 9.5 percent in the city proper—that population is growing in both areas, if slowly.

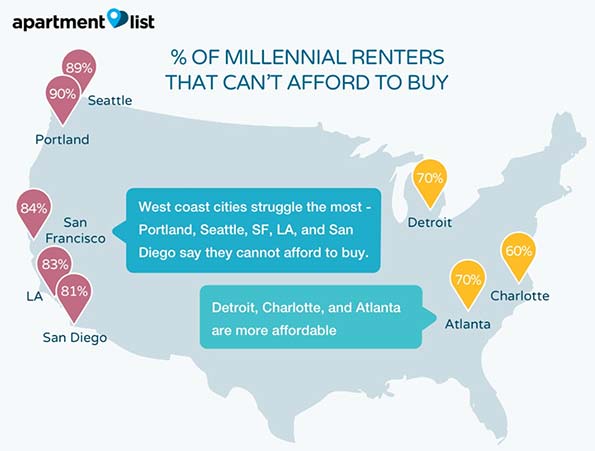

These figures might not be important if they merely reflected a choice by blacks to move to more auspicious locations, but the evidence suggests that specific public policies in these cities have effectively excluded and even driven out blacks. Primary among them are restrictive planning regulations that make it hard to expand the supply of housing. In a market with rising demand and static supply, prices go up. As a rule, a household should spend no more than three times its annual income on a home. But in West Coast markets, housing-price levels far exceed that benchmark. According to the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey, the “median multiple”—the median home price divided by the median household income—should average about 3.0. But the median multiple is 5.1 in Portland, 5.1 in Denver, 5.2 in Seattle, 8.1 in Los Angeles and San Diego, 9.4 in San Francisco, and 9.7 in San Jose. As the Demos/IASP report found, differences in homeownership rates between whites and blacks account for a large share of the racial wealth gap. Policies that put the price of homeownership out of reach for black families exacerbate the problem.

Even some on the left recognize how development restrictions hurt lower- and middle-income people. Liberal commentator Matt Yglesias has called housing affordability “Blue America’s greatest failing.” Yglesias and others criticize zoning policies that mandate single-family homes, or approval processes, like that in San Francisco, that prohibit as-of-right development and allow NIMBYism to keep out unwanted construction—and, by implication, unwanted people. They don’t mention the role of environmental policy in creating these high housing prices. Portland, for example, has drawn a so-called urban-growth boundary that severely restricts land development and drives up prices inside the approved perimeter. The development-stifling effects of the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) are notorious. California also imposes some of the nation’s toughest energy regulations, putting a huge financial burden on lower-income (and disproportionately black) households. Nearly 1 million households in the Golden State spend 10 percent or more of their income on energy bills, according to a Manhattan Institute report by Jonathan Lesser. While liberals are quick to point out that in suburban communities, land-use restrictions that appear race-neutral can be functionally discriminatory, they don’t acknowledge that their own environmental-based restrictions on housing and energy are similarly exclusionary.

The Windy City’s black population loss accounted for the lion’s share of the city’s total shrinkage during the 2000s.

In some cases, western cities’ support for gentrification has come at the expense of long-standing black communities. In Portland, residents of the historically black Albina neighborhood complained about bike lanes—a progressive fetish—being built in their neighborhood. In Oakland, recent upscale arrivals got the government to cite Pleasant Grove Baptist Church, a fixture in the city for 65 years, for creating a public nuisance—because its gospel-choir practice was disturbing the newcomers.

During the Great Migration, cities of the Midwest and the Northeast were industrial magnets, sucking in vast quantities of labor not just from the American South but also from Europe. As northern industry declined during the Rust Belt era, the great northern cities fell on trying times, and black residents, who had struggled to gain equal opportunity in factory jobs and in housing, were hit hard. Racial turbulence, often including riots, intensified, and helped drive a white exodus. Suburb-bound whites left behind an often-impoverished black underclass in segregated neighborhoods that, in many cases, remain so today.

The most distressed cities in this region are the usual suspects: Detroit, Cleveland, Flint, and Youngstown. All have declining black populations, both in their urban cores and region-wide. Others, like St. Louis, have maintained their black populations only through natural increase (births outnumbering deaths). They are losing black residents to migration.

The greatest demographic transition is taking place in Chicago. The Windy City’s black population loss of 177,000 accounted for the lion’s share of the city’s total shrinkage during the 2000s. Another 53,000 blacks have fled the city since 2010. In fact, the entire metro Chicago area lost nearly 23,000 blacks in aggregate, the biggest decline in the United States.

By contrast, in northern cities with more robust middle-class economies—even if job growth doesn’t match Sunbelt levels—black populations are expanding. Since 2010, for example, metro Indianapolis added more than 19,000 blacks (6.9 percent growth), Columbus more than 25,000 (9 percent), and Boston nearly 40,000 (10.2 percent). New York’s and Philadelphia’s black population growth rates are low but positive, in line with slow overall regional growth. Washington, D.C., a traditional hub of black American life, is seeing declining black population share in the district itself, but the overall D.C. region continues to show solid black population growth.

The somewhat unlikely champion for northern black population growth is Minneapolis–St. Paul. Though its black population makes up a much smaller proportion than many of its midwestern peers—at only 8 percent in the region and 19.5 percent in the city—Minneapolis’s black population has grown at a strong rate. Since 2010, the black population in the city has grown by 15,000 people, or 23 percent. The region added 30,400 black residents, growing by 12.1 percent. Part of the Minneapolis story (and that of Columbus as well) involves an influx of Somali immigrants—the metropolitan area has more Somalis than anywhere else in the United States. But immigration doesn’t explain everything. Minneapolis is also the third-leading destination for blacks leaving Chicago (behind Atlanta and Davenport, Iowa). About 1,000 black Chicagoans make the move north every year.

Obviously, many blacks like what they see in places like Minneapolis, Indianapolis, and Columbus. One key is a development environment that keeps housing affordable. This is dramatically clear in Minneapolis, a liberal, historically white city often likened to western cities like Seattle and Denver. But being more housing-development-friendly, and also perhaps in part because of its famously brutal winters, Minneapolis is much more affordable than those cities, with a home-price median multiple of only 3.2. Similarly, in Columbus (with a median multiple of 2.9) and Indianapolis (also 2.9), black families can afford the American dream. When cities get the basics (planning policy, job growth, and reasonable taxation levels) right, even tough winters are no obstacle to a growing population—of whites and blacks.

Where else do blacks go when they leave declining Rust Belt cities? Some seek opportunity in better-off regional cities, but others head to smaller regional communities that, if anything, are even worse off. Census Bureau data suggest that a significant number of blacks leaving Chicago are ending up in struggling downstate Illinois communities like Danville or Carbondale, where they’re unlikely to find economic opportunity. Why move to these places? One answer: they’re dirt cheap. But there’s a particular reason for that—demand has collapsed along with local economies. This creates a false allure. Harvard economist Edward Glaeser noted that some failing cities become so cheap that they turn into “magnets for poor people.” This left-behind population of blacks in places with low opportunity will prove challenging for these regions. The North also remains racially stratified. Milwaukee, New York, and Chicago are the three most segregated regions in the country. The maps of where black and white residents live in cities like Detroit shock the conscience. Urban school districts tasked with educating predominantly black students are failing miserably. Powerful public-employee unions make reform a difficult prospect.

But for those blacks leaving the West, Midwest, and Northeast, one destination dominates: the South. A century ago, in search of economic and social opportunity, blacks were leaving the South to go north and west; today, they are reversing that journey, in what the Manhattan Institute’s Daniel DiSalvo dubbed “The Great Remigration” (Autumn 2012). DiSalvo found that blacks now choose the South in pursuit of jobs, lower costs and taxes, better public services (notably, schools), and sunny weather for retirement. The new arrivals aren’t solely working-class, either. Even better-off blacks, with household incomes over $100,000, are heading south from cities like Chicago.

Historically, Southern blacks lived in rural areas. A large rural black population remains in the South today, often living in the same types of conditions as rural whites, which is to say, under significant economic strain. But the new black migrants to the South are increasingly flocking to the same metro areas that white people are—especially Atlanta, the new cultural and economic capital of black America, with a black population of nearly 2 million. The Atlanta metro area, one-third black, continues to add more black residents (150,000 since 2010 alone) than any other region.

In Texas, Dallas has drawn 110,000 black residents (11.3 percent growth) and Houston just under 100,000 (9.2 percent) since 2010. Austin, a rare liberal city in the South, remains, at 53.4 percent, the whitest major Texas metro—Dallas and Houston double its black population share—but it, too, has seen strong black population growth. Miami, with its powerful Latino presence that includes both historically American as well as Afro-Latinos, also added about 100,000 blacks (8.3 percent). Today, Dallas, Houston, and Miami are all home to more than 1 million black residents.

Many smaller southern cities—including Charlotte, Orlando, Tampa, and Nashville—are also seeing robust black population growth. Even New Orleans has seen a rebound in its black population since 2010. Not surprisingly, these southern cities are extremely affordable. A combination of pro-business policies combined with a development regime that permits housing supply to expand as needed has proved a winner. Among these southern cities, only Miami, with its massive influx of Latin American wealth, is rated as unaffordable, with a median multiple of 5.6. In addition to their sensible policies, many of these southern cities have also viewed their black communities not as a problem to be solved but as a potential civic asset and engine of growth. Atlanta embraced its emerging status as the capital of black America. Houston famously opened its doors and offered temporary shelter to thousands of poor black residents of New Orleans displaced by Hurricane Katrina. Many of those refugees stayed in Houston, attracted by its job opportunities and quality of life.

Blacks are returning to southern cities, like Atlanta, drawn by economic opportunity and lower costs, especially compared with progressive cities like San Francisco, where restrictive housing policies have made living unaffordable for many. JIM WILSON/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX

Blacks are returning to southern cities, like Atlanta, drawn by economic opportunity and lower costs, especially compared with progressive cities like San Francisco, where restrictive housing policies have made living unaffordable for many. JIM WILSON/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX

These regional trends reveal two basic patterns. First, like whites, blacks are attracted by strong, broad-based economies. Pro-growth polices that allow workaday, not just elite, businesses to flourish are foundational to inclusive success. Second, with lower household incomes, black families are vulnerable to high housing costs. A few high-cost cities attract black residents; but for the most part, blacks are flocking to cities that are not only economically vibrant but generally affordable. Even strong urban economies can’t keep blacks from being displaced from cities, such as many on the West Coast, where housing costs remain stratospheric.

Another conclusion revealed by the data: when it comes to how state and local policies affect black residents, the track record of the most liberal cities in the United States is truly dismal. These results should be troubling to progressives touting blue-state planning, economic, and energy policies as models for the nation. After all, if wealthy cities like San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle—where progressives have near-total political control—can’t produce positive outcomes for working-class and middle-class blacks, why should we expect their urban approach to succeed anywhere else?

This piece first appeared at The City Journal.

Aaron M. Renn is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a contributing editor of City Journal, and an economic development columnist for Governing magazine. He focuses on ways to help America’s cities thrive in an ever more complex, competitive, globalized, and diverse twenty-first century. During Renn’s 15-year career in management and technology consulting, he was a partner at Accenture and held several technology strategy roles and directed multimillion-dollar global technology implementations. He has contributed to The Guardian, Forbes.com, and numerous other publications. Renn holds a B.S. from Indiana University, where he coauthored an early social-networking platform in 1991.

Blacks are returning to southern cities, like Atlanta, drawn by economic opportunity and lower costs, especially compared with progressive cities like San Francisco, where restrictive housing policies have made living unaffordable for many. JIM WILSON/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX

Blacks are returning to southern cities, like Atlanta, drawn by economic opportunity and lower costs, especially compared with progressive cities like San Francisco, where restrictive housing policies have made living unaffordable for many. JIM WILSON/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX