From 2009-11, Americans seemed to be clustering again in dense cities, to the great excitement urban boosters. The recently released 2015 Census population estimates confirm that was an anomaly. Americans have strongly returned to their decades long pattern of greater suburbanization and migration to lower-density, lower-cost metropolitan areas, largely in the South, Intermountain West and, most of all, in Texas.

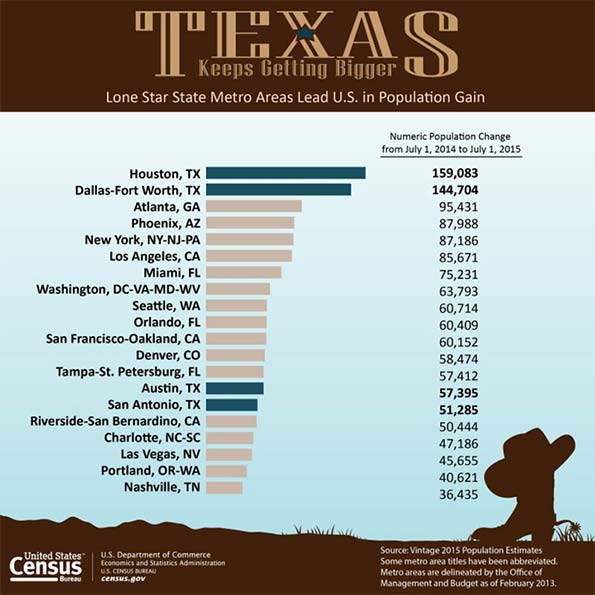

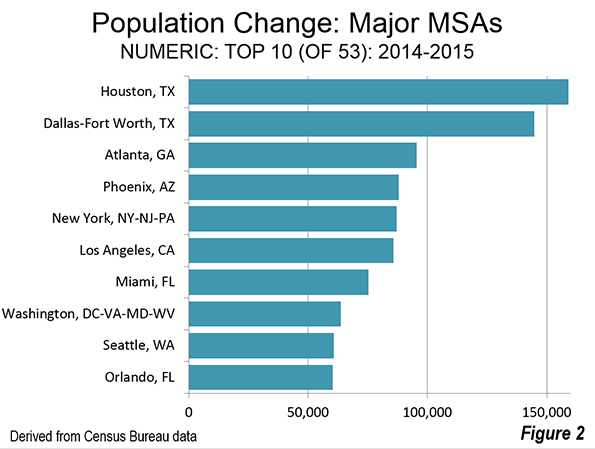

Among the nation’s 53 largest metropolitan statistical areas, the two biggest population gainers between July 1, 2014, and July 1, 2015, were Houston and Dallas-Ft. Worth, together adding roughly 300,000 people. Their growth, in absolute terms, was larger than that of both Los Angeles and New York, which, respectively, are nearly two and three times as populous, notes demographer Wendell Cox. Two other Sun Belt metropolitan areas, Atlanta and Phoenix, also added more people over the year to July 2015 than L.A. and New York.

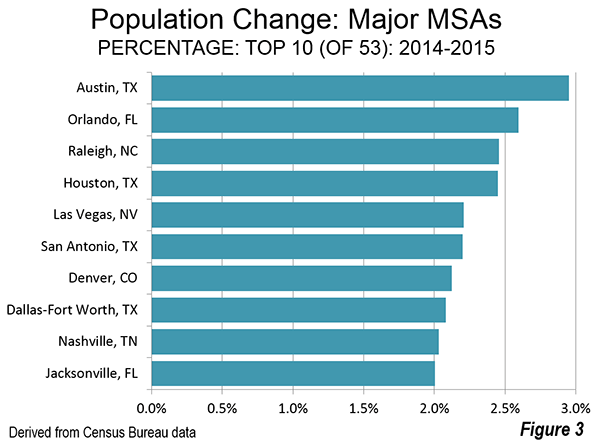

The divergence in growth is even greater when expressed in percentage terms. Of the 10 fastest-growing metro areas in the country, all but two were located in the old Confederacy. Austin ranks first, with 3.0% growth, followed by Orlando, Fla. (2.6%), and Raleigh (2.5%). Other fast-growing southern metro areas included San Antonio, Texas (2.2%); Nashville, Tenn.; and Jacksonville, Fla. (both 2.0%). The fastest growers outside the South are Denver (2.1%) and Las Vegas (2.2%), the latter of which is now clearly back from the dead.

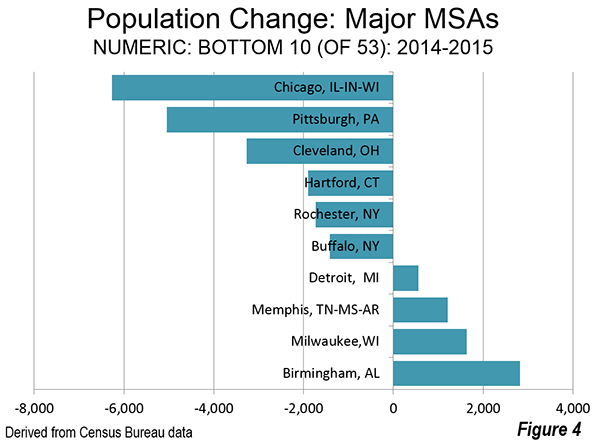

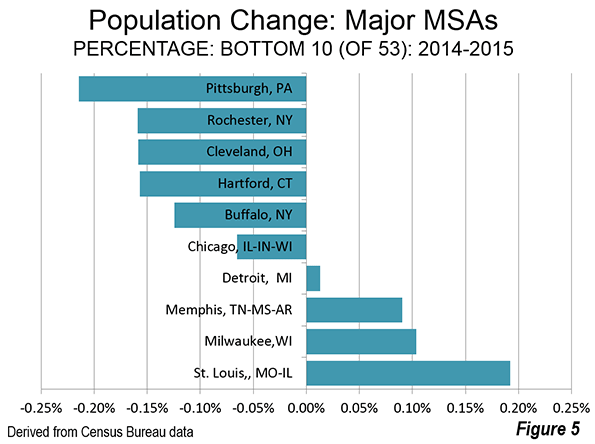

The old big cities aren’t all losing people. New York and Los Angeles’ populations grew as well, 0.43% and 0.65%, respectively, but that’s well below the overall U.S. population growth rate of 0.79% over the same span. Some metro areas, notably Chicago, Pittsburgh, Rochester, Hartford, Cleveland and Buffalo suffered slight losses, while many others, such as St. Louis, Memphis, Milwaukee and Detroit remained essentially stagnant.

Critically, the most recent patterns confirm longer-term trends. Most of the cities at the top of the list are also the ones that have been growing fastest since 2000, led by Raleigh, Austin, and Las Vegas. Also in the top 10 since 2000 are the other three big Texas cities, Phoenix, Charlotte, Orlando and one California metro, largely exurban San Bernardino-Riverside. The slowest growth also follow a similar pattern, with Chicago, several Rust Belt cities, as well as Los Angeles and New York, all in the bottom quintile in percentage terms.

Where Americans Are Moving

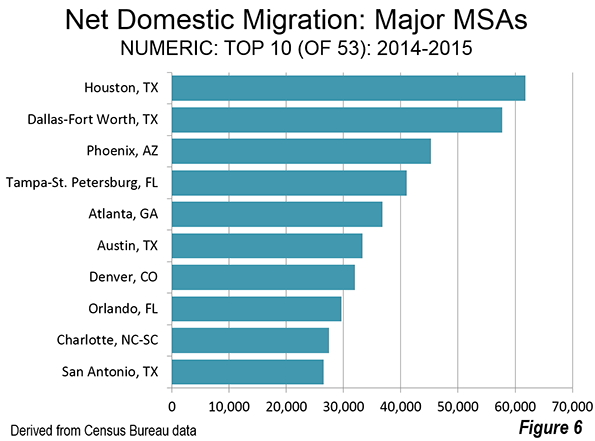

To look ahead to where America will be growing in the future, perhaps the best indicator is net domestic migration. This measures where people are moving, essentially taking their skills, purchasing power and capital with them. Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth enjoyed the largest net gains from domestic migration, roughly 60,000 each, from July 1, 2014, to July 1, 2015, followed by Phoenix, Tampa-St. Petersburg, Atlanta and Austin. The Sun Belt, once written off as doomed by the urbanist punditry, is clearly back.

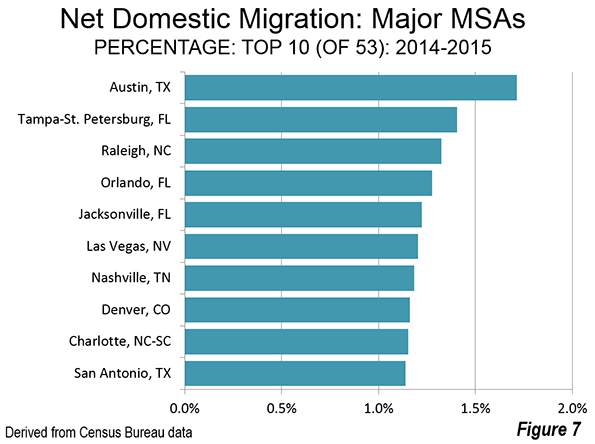

In percentage terms, Austin led the nation, with a population expansion of 1.7% from net domestic migration. The top 10 cities in percentage terms are all in the Sun Belt (Tampa-St. Petersburg ranked second, followed by Raleigh, Orlando and Jacksonville) or the Intermountain West (Denver and Las Vegas).

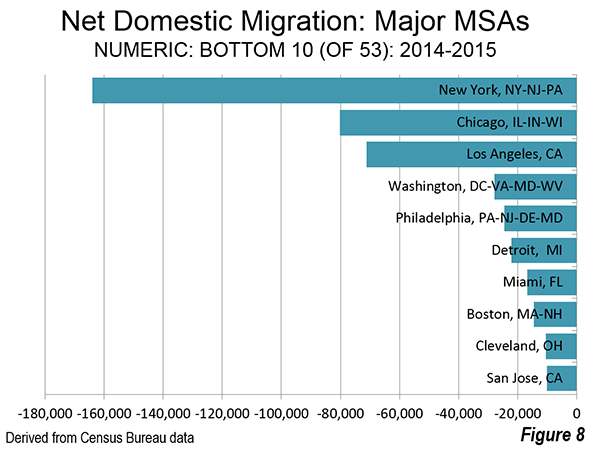

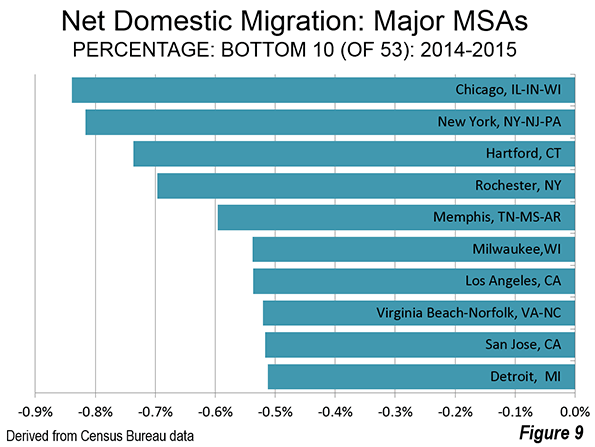

The biggest losers in overall domestic migration are New York (-164,000), Chicago (-80,000) and Los Angeles (-71,000). In percentage terms, Chicago suffered the biggest losses, followed by New York, Hartford, Memphis and Milwaukee. Despite the explosive growth in Silicon Valley, San Jose ranked 9th in percentage loss, just behind 10th place Detroit.

In looking at these trends, the Atlantic’s Derek Thompson, one of the more savvy Census watchers, recently suggested that “it’s 2006 again” as people head out to the Sun Belt metros. When international migration is added to the mix along with the domestic migration numbers, the top five gainers remain in the Sun Belt, led by Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth, which are also becoming meccas for immigrants.

These trends predate the recession. Since 2000, the biggest migration winners in percentage terms are Raleigh, Austin, Las Vegas, Charlotte, Phoenix, and Orlando. In total numbers since 2000 it’s also a familiar list, led by places like Phoenix (net gain: 705,000), Dallas-Ft. Worth (569,000), Atlanta (547,000), Riverside-San Bernardino (513,000) and Houston (496,000).

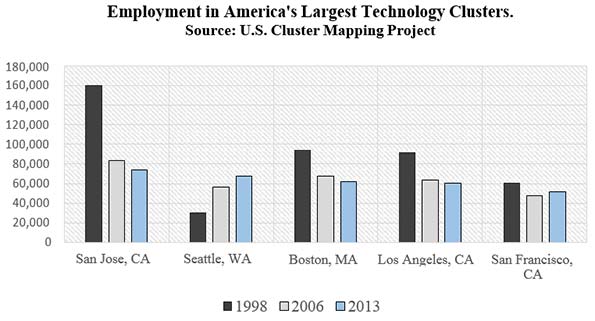

The biggest losers are also familiar, led by the New York metropolitan area, which has lost 2.65 million net migrants since 2000, followed by Los Angeles (negative 1.65 million) and Chicago (down 880,000). Remarkably the two metro areas that have benefited the most from the digitization of the economy are in the loser’s column; between them San Jose and San Francisco lost over 550,000 domestic migrants since 2000.

The Suburban Revival Continues

The other big finding from the new estimates: suburbs are back. In the wake of the housing bust it was widely predicted that the ‘burbs were doomed by high gas prices, millennial preferences and a profound shift of employment to the core cities. The New York Times NYT -0.08% evenpublished fantasies on how the suburban carcass could be carved up, envisioning suburban three-car garages “subdivided into rental units with street front cafés, shops and other local businesses” while abandoned pools would become skateboard parks.

As economist Jed Kolko has noted, the much celebrated era when core cities grew faster than suburbs — the immediate 2009-2011 aftermath of the recession — turned out to be remarkably short-lived. From July 2014-July 2015, only seven out of 53 core cities added more domestic migrants than their suburbs. Of these, the District of Columbia (Washington) could be considered high density urban; the other five core counties are functionally more suburban than urban (Phoenix, Raleigh, Richmond, Sacramento and San Antonio).

Overall domestic migration continues from the core cities to the suburbs. Over the last year core counties lost a net 185,000 domestic migrants, while the suburban counties gained 187,000.

Looking Ahead

These trends are likely to continue as long as the economy achieves even modest growth. One big factor will be the migration of millennials, now headed increasingly to Sun Belt cities and suburbs. Since 2010, among educated millennials, the fastest growth in migration has been to such lower-cost regions as Atlanta, Orlando, New Orleans, Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, Pittsburgh, Columbus, and even Cleveland.

This is largely a product of high housing prices. According to Zillow, rents claim upward of 45% of income in Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, and Miami compared to less than 30% of income in places like Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston. The costs of purchasing a house are even more lopsided: in Los Angeles and the Bay Area, a monthly mortgage takes, on average, close to 40% of income, compared to 15% nationally.

Millennials are also headed increasingly to the suburbs. According to the National Association of Realtors, 80% of the homes purchased by millennials between 2013 and 2014 were detached houses, and 8% had chosen attached housing. This trend will accelerate in the next few years, suggests Kolko, as the peak of the millennial wave turns 30.

Similarly immigrants — the other big driver shaping our future geography — are also moving increasingly to Sun Belt cities such as Houston, Dallas-Ft, Worth and Atlanta, as newcomers seek out both economic opportunities and lower housing prices. New York remains the immigrant leader, with the foreign-born population increasing by 600,000 since 2000, but second place Houston, a relatively newcomer magnet for immigrants, gained 400,000, more than Chicago and the Bay Area combined. The regions experiencing the highest growth in newcomers in percentage terms were Charlotte and Nashville, which each have seen their foreign-born populations double.

In the coming decade, immigrants and millennials will produce the vast majority of the country’s children — and they increasingly sending them to school in the suburbs of Sun Belt cities. Central (urban core) areas lost substantial numbers of schoolchildren between 2000 and 2010, while school populations rose in newer suburbs and exurbs. Overall the child populations in cities such as Austin, Houston, San Antonio, Raleigh, Orlando and Nashville are on the rise while dropping in places like Los Angeles and Chicago, as well as some Rust Belt cities.

America’s geography will be increasingly dominated by Sun Belt cities as well as suburbs. This challenges the preferred narrative among most planners and the mainstream media, as well as some developers who believe more Americans desire to live in high cost, high density locales. Some day perhaps the facts — as seen both in this year’s numbers and longer term trends — will intrude on the narrative. Dispersion is back, and getting stronger. It’s time that developers, planners and the media adjust to the facts, rather than just reflect their prejudices.

| Population Change in the Nation’s Largest Metropolitan Areas, 2014-2015 | |||||

| Change Rank | Region | 2014 Population | 2015 Population | 14-15 Change | % Change |

| 1 | Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land, TX | 6,497,864 | 6,656,947 | 159,083 | 2.4 |

| 2 | Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX | 6,958,092 | 7,102,796 | 144,704 | 2.1 |

| 3 | Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Roswell, GA | 5,615,364 | 5,710,795 | 95,431 | 1.7 |

| 4 | Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, AZ | 4,486,543 | 4,574,531 | 87,988 | 2 |

| 5 | New York-Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ-PA | 20,095,119 | 20,182,305 | 87,186 | 0.4 |

| 6 | Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA | 13,254,397 | 13,340,068 | 85,671 | 0.6 |

| 7 | Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach, FL | 5,937,100 | 6,012,331 | 75,231 | 1.3 |

| 8 | Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV | 6,033,891 | 6,097,684 | 63,793 | 1.1 |

| 9 | Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA | 3,672,866 | 3,733,580 | 60,714 | 1.7 |

| 10 | Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL | 2,326,729 | 2,387,138 | 60,409 | 2.6 |

| 11 | San Francisco-Oakland-Hayward, CA | 4,595,980 | 4,656,132 | 60,152 | 1.3 |

| 12 | Denver-Aurora-Lakewood, CO | 2,755,856 | 2,814,330 | 58,474 | 2.1 |

| 13 | Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL | 2,917,813 | 2,975,225 | 57,412 | 2 |

| 14 | Austin-Round Rock, TX | 1,943,465 | 2,000,860 | 57,395 | 3 |

| 15 | San Antonio-New Braunfels, TX | 2,332,790 | 2,384,075 | 51,285 | 2.2 |

| 16 | Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA | 4,438,715 | 4,489,159 | 50,444 | 1.1 |

| 17 | Charlotte-Concord-Gastonia, NC-SC | 2,379,177 | 2,426,363 | 47,186 | 2 |

| 18 | Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise, NV | 2,069,146 | 2,114,801 | 45,655 | 2.2 |

| 19 | Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro, OR-WA | 2,348,607 | 2,389,228 | 40,621 | 1.7 |

| 20 | Nashville-Davidson–Murfreesboro–Franklin, TN | 1,793,910 | 1,830,345 | 36,435 | 2 |

| 21 | Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA-NH | 4,739,385 | 4,774,321 | 34,936 | 0.7 |

| 22 | San Diego-Carlsbad, CA | 3,265,700 | 3,299,521 | 33,821 | 1 |

| 23 | Raleigh, NC | 1,243,035 | 1,273,568 | 30,533 | 2.5 |

| 24 | Sacramento–Roseville–Arden-Arcade, CA | 2,244,879 | 2,274,194 | 29,315 | 1.3 |

| 25 | Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI | 3,495,656 | 3,524,583 | 28,927 | 0.8 |

| 26 | Jacksonville, FL | 1,421,004 | 1,449,481 | 28,477 | 2 |

| 27 | Columbus, OH | 1,997,308 | 2,021,632 | 24,324 | 1.2 |

| 28 | San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA | 1,954,348 | 1,976,836 | 22,488 | 1.2 |

| 29 | Oklahoma City, OK | 1,337,619 | 1,358,452 | 20,833 | 1.6 |

| 30 | Indianapolis-Carmel-Anderson, IN | 1,971,861 | 1,988,817 | 16,956 | 0.9 |

| 31 | Kansas City, MO-KS | 2,071,283 | 2,087,471 | 16,188 | 0.8 |

| 32 | Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD | 6,053,720 | 6,069,875 | 16,155 | 0.3 |

| 33 | Salt Lake City, UT | 1,154,513 | 1,170,266 | 15,753 | 1.4 |

| 34 | Richmond, VA | 1,259,685 | 1,271,334 | 11,649 | 0.9 |

| 35 | New Orleans-Metairie, LA | 1,251,962 | 1,262,888 | 10,926 | 0.9 |

| 36 | Baltimore-Columbia-Towson, MD | 2,786,853 | 2,797,407 | 10,554 | 0.4 |

| 37 | Grand Rapids-Wyoming, MI | 1,028,962 | 1,038,583 | 9,621 | 0.9 |

| 38 | Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN | 2,148,450 | 2,157,719 | 9,269 | 0.4 |

| 39 | Louisville/Jefferson County, KY-IN | 1,271,172 | 1,278,413 | 7,241 | 0.6 |

| 40 | Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC | 1,717,853 | 1,724,876 | 7,023 | 0.4 |

| 41 | Tucson, AZ | 1,004,244 | 1,010,025 | 5,781 | 0.6 |

| 42 | St. Louis, MO-IL | 2,806,191 | 2,811,588 | 5,397 | 0.2 |

| 43 | Providence-Warwick, RI-MA | 1,609,533 | 1,613,070 | 3,537 | 0.2 |

| 44 | Birmingham-Hoover, AL | 1,142,823 | 1,145,647 | 2,824 | 0.2 |

| 45 | Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI | 1,574,115 | 1,575,747 | 1,632 | 0.1 |

| 46 | Memphis, TN-MS-AR | 1,342,914 | 1,344,127 | 1,213 | 0.1 |

| 47 | Detroit-Warren-Dearborn, MI | 4,301,480 | 4,302,043 | 563 | 0 |

| 48 | Buffalo-Cheektowaga-Niagara Falls, NY | 1,136,642 | 1,135,230 | -1,412 | -0.1 |

| 49 | Rochester, NY | 1,083,678 | 1,081,954 | -1,724 | -0.2 |

| 50 | Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT | 1,213,225 | 1,211,324 | -1,901 | -0.2 |

| 51 | Cleveland-Elyria, OH | 2,064,079 | 2,060,810 | -3,269 | -0.2 |

| 52 | Pittsburgh, PA | 2,358,096 | 2,353,045 | -5,051 | -0.2 |

| 53 | Chicago-Naperville-Elgin, IL-IN-WI | 9,557,294 | 9,551,031 | -6,263 | -0.1 |

This piece originally appeared in Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, will be published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.