Recently, The Wall Street Journal and Newsday, in a photographic spread, trumpeted the 70th anniversary of Levittown, the New York suburban development that provided the model for much of the rapid suburbanization that occurred after the Second World War in the United States. Levittown’s production line building also set the stage for the similar suburbs of cities in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and elsewhere.

Over the last seven decades, the United States has become a predominantly suburban nation. In 2011-2015, 85 percent of the population in the 53 major metropolitan areas (over 1,000,000 population) lived in the suburbs or exurbs. This is based on analysis at the small area level (zip code tabulation areas) from the American Community Survey that classifies population based on demographic data (Figure 1).

Generally similar findings have been made about Canada and Australia by research teams led by Professor David L. A. Gordon of Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. Gordon and his Canadian team pioneered this type of analysis, which is not dependent on core municipality versus surrounding area analysis. Core municipalities often do not reflect the realities of metropolitan areas because they vary so greatly in their share of metropolitan area population. For example, the city of Atlanta has only 8 percent of the metropolitan area population, while San Antonio has more than 60 percent of the metropolitan area population.

Suburban Nation: United States

Many people, including urban analysts, are unaware of the extent to which American cities have become suburbanized. But the former mono-centricity that characterized most metropolitan areas at the end of World War II has been replaced first by multi-centered suburban employment development (polycentricity) and more recently by dispersion of employment. As early as 2000, more people worked in dispersed worksites in the major metropolitan areas, including New York, than in the downtowns (CBD’s) and suburban office centers, according to research by Bumsoo Lee and Peter Gordon. City Sector Model analysis shows that CBDs lost two percent of their market share from 2000 to 2015, based on a City Sector Analysis of County Business Patterns data. It seems likely that the trend of dispersion has continued (Figure 2).

We took a look at the population distribution of the 53 major metropolitan areas (those with more than 1,000,000 population) to rate down by the extent to which they are suburban. The City Sector Model classifies the population of any area where there is an employment density of 20,000 or more as a CBD considers the urban core inner ring to have population densities exceeding 7500 per square mile. Such densities were characteristic of pre-automobile urban areas in the United States. According to estimates prepared by the Urban Land Institute, in 1920 the 24 urban areas with more 250,000 residents had an average population density of 7500.

As it turns out, 10 metropolitan areas have virtually no urban core population by this definition. To rank these metropolitan areas by their extent of suburbanization, we broke the 10 way tie by ranking the metropolitan areas by the extent of their exurban population. Exurban areas have very low population densities (250 per square mile or less) and are generally outside the urban area, which includes all contiguous built up area, surrounded by rural territory.

Seven of the 10 most suburban cities are in three states. Three are in Florida and two each in North Carolina and Arizona. They are listed in the Table 1, and data is provided for all 53 in Table 2.

| Table 1 |

|

| Most Suburban Cities: (Metroplitan Areas) |

| 1 |

Charlotte, NC-SC |

| 2 |

Riverside-San Bernardino, CA |

| 3 |

Raleigh, NC |

| 4 |

Orlando, FL |

| 5 |

Birmingham, AL |

| 6 |

Jacksonville, FL |

| 7 |

Phoenix, AZ |

| 8 |

San Antonio, TX |

| 9 |

Tampa-St. Petersburg, FL |

| 10 |

Tucson, AZ |

|

|

| Out of 53 with more than 1,000,000 population |

The Most Suburban: Charlotte, NC-SC

Charlotte turns out to be the country’s most suburban metropolitan area. The exurban commuting patterns of Charlotte expanded substantially over the 2000 to 2010 decade, which resulted in the largest geographic expansion of any major metropolitan area. Its exurban population is 51 percent and its urban population density is approximately 1,700.

2nd Most Suburban: Riverside-San Bernardino, CA

Second ranked Riverside-San Bernardino, which in many ways is an extension of the Los Angeles metropolitan area (and is included in the Los Angeles combined statistical area), ranked as the second most suburban city. However, like other California cities, Riverside-San Bernardino is comparatively dense as an urban area, ranking above both Chicago and world renown densification model Portland as the 11th densest major urban area in the nation.

3rd Most Suburban: Raleigh, NC

At the opposite end of the density scale is third ranked Raleigh, a high tech center with an exurban population of 42 percent. Raleigh has an urban area population density of approximately 1,700, about the same as top ranked Charlotte and 16th ranked Atlanta.

4th Most Suburban: Orlando, FL

Fourth ranked Orlando has an exurban population of 34 percent and is suburban by nature. This is not surprising considering that it is virtually all new, having principally been developed since Walt Disney World made its decision to locate there and other entertainment venues followed.

5th Most Suburban: Birmingham, AL

Fifth ranked Birmingham, Alabama’s largest city, had far slower growth than most major metropolitan areas of the South. In 1950, the metropolitan population was approximately 20 percent behind Atlanta, according to the 1950 census. Now, virtually all-suburban Atlanta has grown to nearly 5 times that of Birmingham since that time. Even so, Birmingham has expanded to have the lowest density of any principal urban area in a major metropolitan area.

6th Most Suburban: Jacksonville, FL

Sixth ranked Jacksonville, another all-suburban metropolitan area has an exurban population of 25 percent.

7th Most Suburban: Phoenix, AZ

Phoenix, like Orlando is virtually all a postwar product. With its 100 percent suburban population, 19 percent of it is in the exurbs ranking Phoenix as seventh most suburban. Phoenix is the largest among the all-suburban cities, with more than 4.6 million residents and is likely to displace San Francisco to become the nation’s 11th largest metropolitan area this year, and could take 10th position away from Boston by the 2020 Census.

8th Most Suburban: San Antonio, TX

San Antonio, ranked as eighth most suburban, with an exurban population of 17 percent.

9th Most Suburban: Tampa-St. Petersburg, FL

Tampa – St. Petersburg ranks as the ninth most suburban city, with a 14 percent exurban population. Like San Antonio, Tampa has a comparatively strong downtown area, but its inner densities do not reach the levels necessary for population to be classified as urban core.

10th Most Suburban: Tucson, AZ

Tucson, the newest entry among the nations 53 major metropolitan areas takes the 10th position and rounds out the cities that are 100 percent suburban.

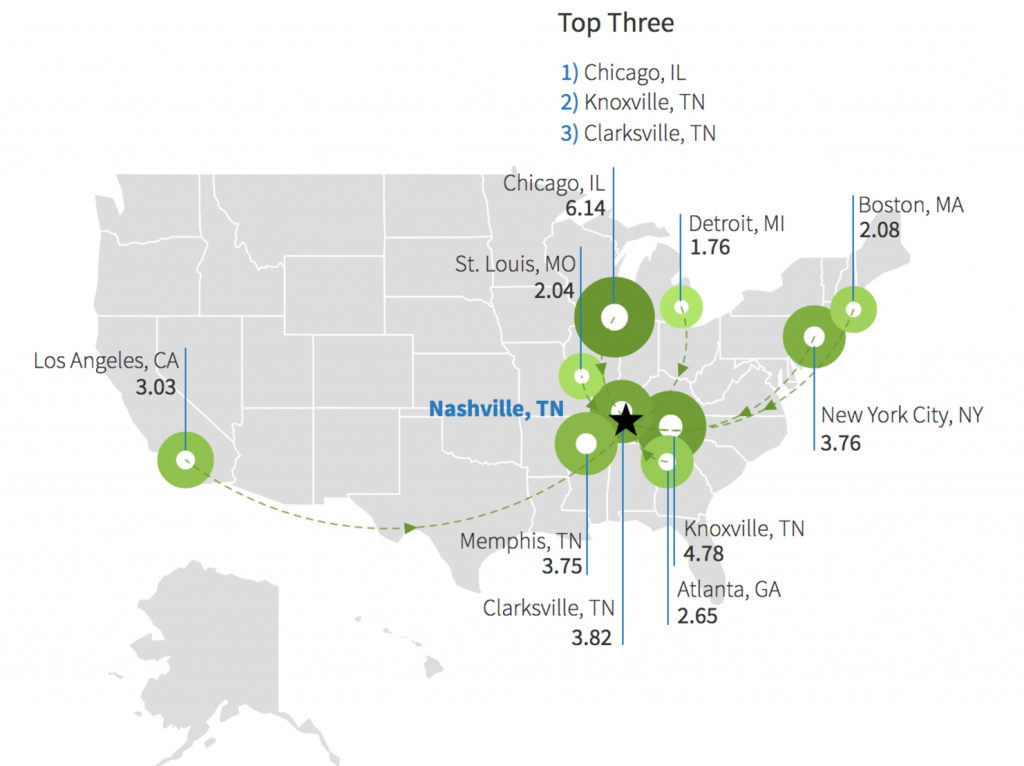

Other Cities

Nashville and San Jose ranked 11th, but are very different. Nashville, as the capital of Tennessee, has a comparatively strong CBD, but the urban area is one of the least dense. On the other hand, San Jose, which is really an extension of the San Francisco metropolitan area and a part of the San Francisco Bay combined statistical area has a weak CBD, but a very high urban area density. San Jose ranks after only Los Angeles and San Francisco in its urban density and ahead of the sprawling New York urban area.

There are a total of 34 metropolitan areas that are 95 percent or more suburban. These include examples such as Atlanta, at 99.2 percent San Diego at 98.9 percent Sacramento at 98.3 percent, Austin and 97.9 percent, Denver at 96.9 percent and Portland at 90.0 percent.

Los Angeles, with the nation’s densest urban area, is 89.4 percent suburban, nearly matched by Seattle’s 89.3 percent.

A number of older cities are overwhelmingly suburban as well, such as St. Louis at 88.4 suburban, Minneapolis-St. Paul at 86.8 percent, Washington at 83.3 percent, and Milwaukee at 76.6 percent. Chicago, Philadelphia, Providence, San Francisco – Oakland and Buffalo are all more than 70 percent suburban.

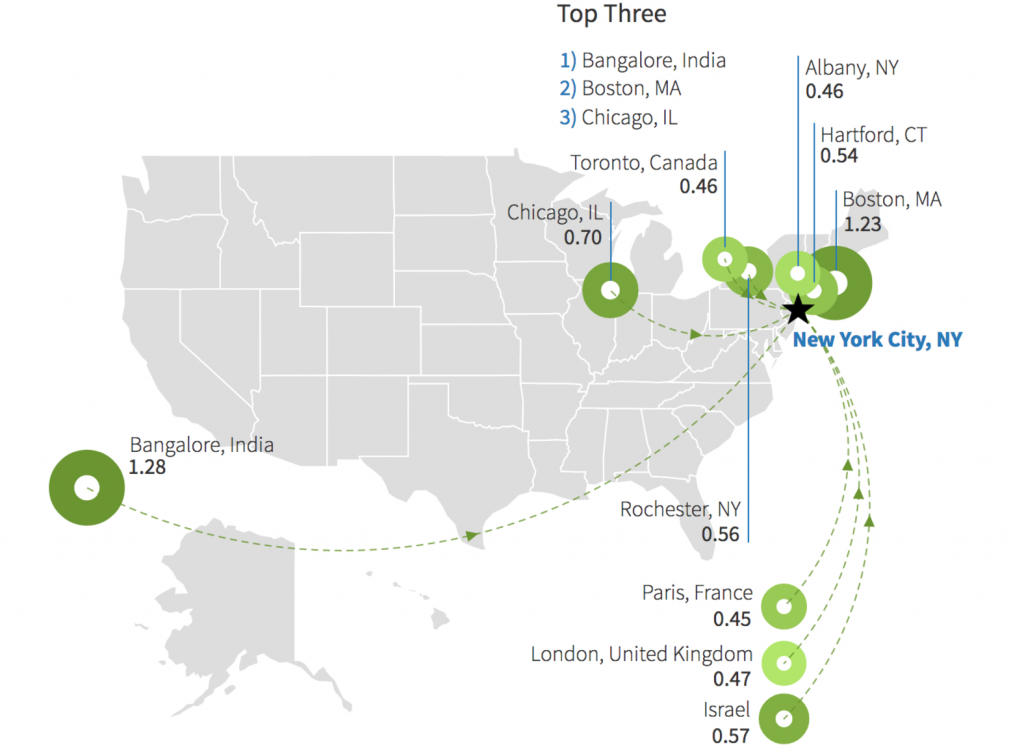

Boston and New York are considerably less suburban than the other 51 major metropolitan areas. Boston is 64.3 percent suburban, while New York is the only major metropolitan area that has a larger urban core population than its suburban and exurban area. New York is only 46.7 percent suburban.

Fast Growing and Automobile Oriented

As with all suburban areas, these suburban cities are automobile oriented. The journey to work transit market shares average 1.7 percent, one third of the national average for all areas. They are also among the fastest growing, with six ranking in the top 10 for 2010 to 2016 growth. A close look shows that the American urban form is changing, but not in ways commonly discussed among planners, urban land speculators and many academics.

| Table 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cities (Metropolitan Areas) Ranked by Extent of Suburbanization |

| Major Metropolitan Areas: 2011-2015 |

|

|

|

Share (%) of Metropolitan Population by Sector |

| Rank |

Metropolitan Area |

% Suburban |

CBD |

Urban Core: Inner Ring |

Earlier Suburbs |

Later Suburbs |

Exurbs |

| 1 |

Charlotte, NC-SC |

100.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

10.2% |

39.2% |

50.6% |

| 2 |

Riverside-San Bernardino, CA |

100.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

28.9% |

29.6% |

41.5% |

| 3 |

Raleigh, NC |

100.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

7.4% |

56.8% |

35.8% |

| 4 |

Orlando, FL |

100.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

15.7% |

50.6% |

33.7% |

| 5 |

Birmingham, AL |

100.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

41.6% |

25.2% |

33.2% |

| 6 |

Jacksonville, FL |

100.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

25.6% |

49.0% |

25.4% |

| 7 |

Phoenix, AZ |

100.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

29.1% |

52.0% |

18.9% |

| 8 |

San Antonio, TX |

100.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

38.6% |

44.1% |

17.3% |

| 9 |

Tampa-St. Petersburg, FL |

100.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

44.2% |

41.7% |

14.1% |

| 10 |

Tucson, AZ |

100.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

46.9% |

41.0% |

12.2% |

| 11 |

Nashville, TN |

99.8% |

0.2% |

0.0% |

24.4% |

36.9% |

38.5% |

| 12 |

San Jose, CA |

99.8% |

0.1% |

0.1% |

77.5% |

9.3% |

13.0% |

| 13 |

Houston, TX |

99.6% |

0.4% |

0.0% |

33.2% |

50.0% |

16.4% |

| 14 |

Dallas-Fort Worth, TX |

99.5% |

0.2% |

0.3% |

33.7% |

43.1% |

22.7% |

| 15 |

Virginia Beach-Norfolk, VA-NC |

99.5% |

0.0% |

0.5% |

45.9% |

38.0% |

15.7% |

| 16 |

Atlanta, GA |

99.2% |

0.2% |

0.6% |

14.8% |

70.8% |

13.6% |

| 17 |

San Diego, CA |

98.9% |

0.0% |

1.1% |

61.3% |

30.9% |

6.7% |

| 18 |

Sacramento, CA |

98.3% |

0.0% |

1.7% |

37.7% |

40.9% |

19.8% |

| 19 |

Memphis, TN-MS-AR |

98.1% |

0.0% |

1.9% |

39.9% |

35.3% |

23.0% |

| 20 |

Austin, TX |

97.9% |

0.4% |

1.7% |

15.4% |

63.0% |

19.6% |

| 21 |

Las Vegas, NV |

97.6% |

0.4% |

2.0% |

16.2% |

77.7% |

3.8% |

| 22 |

Oklahoma City, OK |

97.2% |

0.4% |

2.4% |

34.1% |

32.6% |

30.6% |

| 23 |

Miami, FL |

97.1% |

0.3% |

2.6% |

50.0% |

44.8% |

2.4% |

| 24 |

Denver, CO |

96.9% |

0.5% |

2.7% |

42.7% |

42.7% |

11.4% |

| 25 |

Grand Rapids, MI |

96.5% |

0.0% |

3.5% |

33.0% |

15.4% |

48.0% |

| 26 |

Salt Lake City, UT |

96.5% |

0.0% |

3.5% |

47.9% |

39.2% |

9.3% |

| 27 |

Richmond, VA |

95.6% |

0.0% |

4.4% |

38.5% |

38.4% |

18.6% |

| 28 |

Columbus, OH |

95.3% |

0.0% |

4.7% |

28.5% |

38.6% |

28.3% |

| 29 |

Indianapolis. IN |

95.0% |

0.3% |

4.6% |

27.3% |

42.6% |

25.2% |

| 30 |

Kansas City, MO-KS |

94.8% |

0.2% |

5.0% |

37.5% |

26.9% |

30.4% |

| 31 |

Detroit, MI |

93.7% |

0.1% |

6.1% |

60.2% |

16.6% |

17.0% |

| 32 |

Louisville, KY-IN |

91.2% |

0.5% |

8.3% |

44.5% |

26.0% |

20.8% |

| 33 |

Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN |

90.0% |

0.6% |

9.4% |

40.3% |

27.9% |

21.8% |

| 34 |

Portland, OR-WA |

90.0% |

0.7% |

9.3% |

36.0% |

39.7% |

14.3% |

| 35 |

Los Angeles, CA |

89.4% |

0.4% |

10.1% |

76.1% |

5.3% |

8.0% |

| 36 |

Seattle, WA |

89.3% |

1.1% |

9.7% |

35.9% |

40.7% |

12.6% |

| 37 |

New Orleans. LA |

89.1% |

0.2% |

10.7% |

50.3% |

7.0% |

31.8% |

| 38 |

Hartford, CT |

88.7% |

0.1% |

11.2% |

77.4% |

1.0% |

10.3% |

| 39 |

Rochester, NY |

88.6% |

0.3% |

11.1% |

46.8% |

7.9% |

34.0% |

| 40 |

St. Louis,, MO-IL |

88.4% |

0.1% |

11.5% |

39.6% |

26.1% |

22.7% |

| 41 |

Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN-WI |

86.8% |

0.5% |

12.7% |

31.4% |

33.7% |

21.7% |

| 42 |

Baltimore, MD |

84.3% |

1.4% |

14.3% |

42.0% |

20.6% |

21.8% |

| 43 |

Pittsburgh, PA |

84.1% |

1.3% |

14.5% |

56.0% |

5.0% |

23.1% |

| 44 |

Washington, DC-VA-MD-WV |

83.3% |

1.6% |

15.1% |

28.2% |

36.6% |

18.4% |

| 45 |

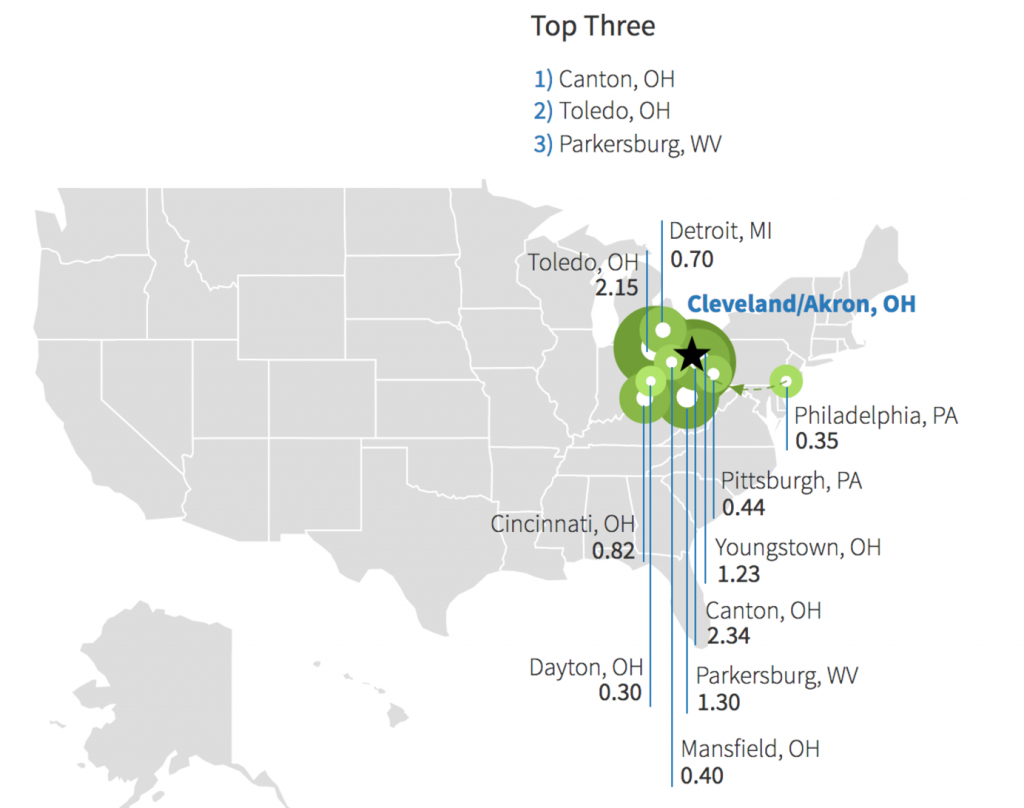

Cleveland, OH |

78.3% |

0.0% |

21.7% |

48.5% |

13.6% |

16.2% |

| 46 |

Milwaukee,WI |

76.6% |

1.6% |

21.7% |

50.7% |

10.5% |

15.4% |

| 47 |

Chicago, IL-IN-WI |

74.2% |

1.2% |

24.6% |

44.9% |

18.5% |

10.8% |

| 48 |

Philadelphia, PA-NJ-DE-MD |

74.1% |

0.9% |

25.0% |

50.5% |

15.1% |

8.5% |

| 49 |

Providence, RI-MA |

73.9% |

0.6% |

25.5% |

47.9% |

2.8% |

23.1% |

| 50 |

San Francisco-Oakland, CA |

73.0% |

3.3% |

23.7% |

54.0% |

7.6% |

11.4% |

| 51 |

Buffalo, NY |

71.0% |

0.3% |

28.7% |

51.3% |

3.1% |

16.6% |

| 52 |

Boston, MA-NH |

64.3% |

3.2% |

32.5% |

48.6% |

3.6% |

12.2% |

| 53 |

New York, NY-NJ-PA |

46.7% |

6.5% |

46.8% |

35.2% |

5.5% |

6.0% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Derived from American Community Survey using City Sector Model |

|

|

|

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Top photograph: Exurban Charlotte, by author.