“[T]he city as World icon is being destroyed, not by being secularized (it was always secular at base with some sacral potencies shooting through it from every angle) but by being radically profaned. The city has become the playground not of Wisdom but the battleground of savages, as in Belfast and Beirut. The city’s sacral potentialities have been removed and invested in the sovereign individual. Its central workshop, where radical transactions with reality used to summon a citizenry to meet in peace, was given notice that its lease was up. The center gave way to parking lots and bus stops; discourse fractured, politics increasingly issued from the mouths of ideological gurus, and the sovereign individual was relegated to suburban sprawls focused on the centers of consumption called shopping malls. Here anxiety and frustration mounted as identity waned.”

– Aidan Kavanagh, o.s.b., On Liturgical Theology, New York: Pueblo Publishing Company, 1984, p. 26.

The church and the city

The Benedictine monk Aidan Kavanagh, who straddled two worlds as both a monk and a Yale divinity professor, proposes that we understand the Church as originally and centrally an urban phenomenon. He translates civitas as “workshop” and “playground,” the space in which social, philosophical, and even scientific questions are worked out by humans in contact with their God, “the locale of human endeavor par excellence.”

By the fifth century A.D., Christian worship in the great cities of Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, Rome, and Constantinople had become not just one service, but an “interlocking series of services” that began at daybreak with laudes and ended at dusk with lamp-lighting and vespers. Only the most pious participated in all the services, but everyone participated in some. The rites “gave form not only to the day itself but to the entire week, the year, and time itself,” says Kavanagh.

Perhaps just as important as the transformation of time was the transformation of space, for the mid-morning assemblages and processions appropriated the entire neighborhood as space for worship. Participants met in a designated place in some neighborhood or open space, and proceeded to the church designated for the day, picking up more participants as they went, and “pausing here and there for rest, prayer, and more readings from the Bible.” The Eucharist itself was a “rather rowdy affair of considerable proportions,” kinetic and free of stationary pews.

Kavanagh contrasts this with modern worship, which he characterizes as “a pastel endeavor shrunk to only forty-five minutes and consisting of some organ music, a choral offering, a few lines of scripture, a short talk on religion, a collection, and perhaps a quick consumption of disks or pellets and a beverage.”

The American urban design pattern

Kavanagh identifies several influences weakening the urban Church as civitas. The many churches developed many different liturgies, resulting in what he calls “liturgical hypertrophy.” These were flattened and standardized, shrunk to centrally-manageable size and legible doctrinal authority, by the English Act of Uniformity of 1549 and the Council of Trent by 1614. At the same time, printed books ushered in the new literary consciousness, eroding the power of community ritual consciousness for European Christians.

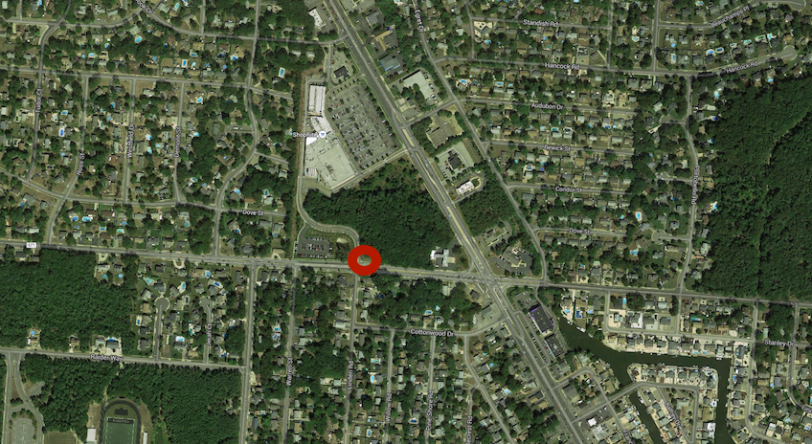

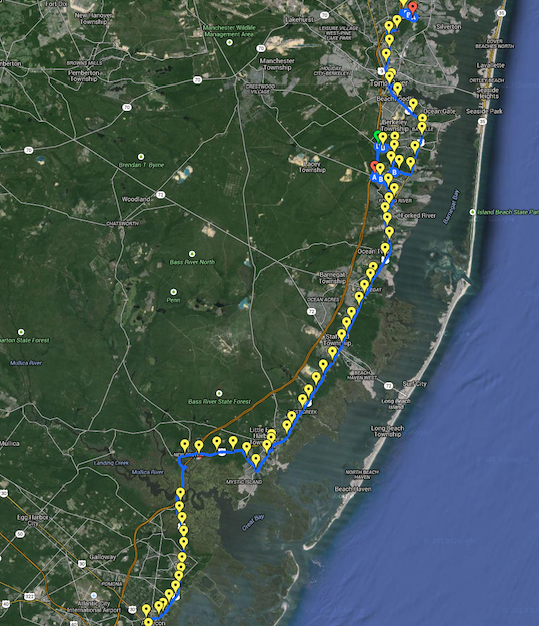

But ancient religious practices (and their modern elaborations) are still performed in Europe; processions may still be seen winding through the streets of cities and small towns. Except for the occasional Palm Sunday procession, they are all but absent in the United States. The American urban design pattern — increasingly spreading even to small towns — is forbidding to the kind of religious practice that transforms space and time.

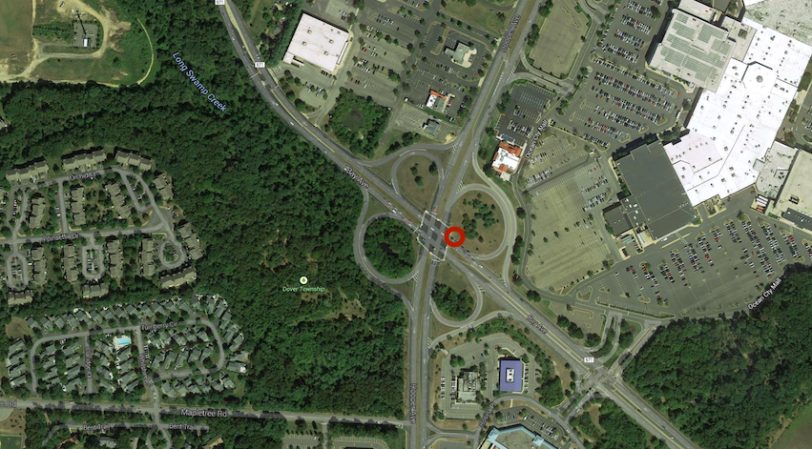

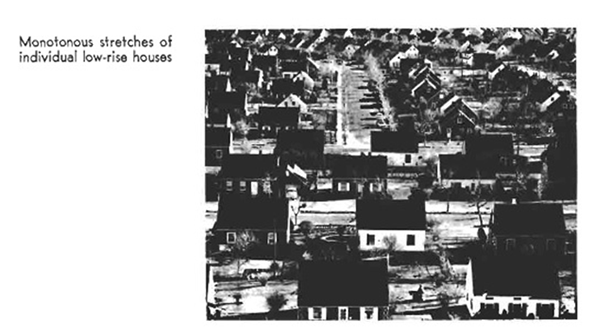

The American urban design pattern is characterized by, first, an orientation toward the automobile above all else; second, toward consumption as the main activity besides work; and third, toward efficient human storage. Human activities other than consumption and “being stored” – as in day cares, schools, prisons, offices, nursing homes, and “housing units” themselves – are made difficult and uncomfortable by the physical built environment itself. Religious activity and social activity, two main components of human flourishing that transform local environments, are increasingly rare and emptied of transformative power.

A Pattern Language (Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, and Murray Silverstein, New York: Oxford University Press, 1977) is a humane vision of urban and architectural design, focused on the activities of human flourishing. The authors present 253 interlocking patterns, from macro (Pattern 8, Mosaic of Subcultures) to micro (Pattern 251, Different Chairs — because people come in different sizes!), demonstrating how physical space constrains or facilitates the activities of peopling.

A secular book, it does not offer any patterns for churches, though it offers Sacred Space and Holy Ground. Alexander et al. hope that merely offering conducive space will allow proper ritual to spontaneously develop. Certainly, the absence of such space precludes such rituals.

A typical pattern is Pattern 88, the Street Café: “The street café provides a unique setting, special to cities: a place where people can sit lazily, legitimately, be on view, and watch the world go by.” These occur all over Europe, but are rare in the United States. In my old neighborhood in Hollywood, California, there were sidewalk cafés, but people drove from distant neighborhoods, parked their cars, and sat mostly watching automobile traffic. An analogy can be drawn to the city church with a parking lot: its ability to transform space, to claim the city as its own for its own activities, is limited. This kind of café becomes more a place of human storage than for the positive activity of being on view and watching the world go by. Churches, and the religious activity centered on them, may face the same constraint.

Praying in the streets

One of Alexander et al.’s patterns is Pattern 63: Dancing in the Street, a poignant pattern given center stage in Barbara Ehrenreich’s book Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy. When the physical pathways of connection are reserved for driving, they are closed off from normal, healthy human activities. Much fearful (and regulatory) attention has been paid in recent years to the Muslim practice of praying in the streets in European cities such as Paris and Nice; we can respectfully observe, at least, that faith allows them to transform profane space into space for ritual observance. Still, this practice has not been translatable into the United States; it occurs in New York City, only once a year, with proper permits acquired beforehand.

American streets are not places where ritual, either religious or secular, is easily performed. Only in cloistered communities, set apart from the flows of American life, is this possible, as in the Orthodox Jewish communities of New York and Los Angeles. There, people (importantly) walk to temple, and participate in an “interlocking series” of rituals throughout the Sabbath. During the numerous Great Awakenings in the United States, open space was transformed into religious space through its key ritual, the revival; but this was a temporary transformation, and has not survived in contemporary ritual.

The reinvigoration of religious and social ritual — allowing people to flourish, rather than merely consume and be stored — is as much an urban design problem as a social problem. But there is another characteristic of American civic life, other than its distinctive urban design pattern, that makes praying in the streets so rare: our studied indifference and polite disattention, our lack of perceptible solidarity, summarized by Randall Collins thus:

“Public interaction is an equality without much solidarity, an enactment of personal distance mitigated by a tinge of mutual politeness and shared casualness. Goffman calls it the order of civil disattention. As Goffman notes, this is not merely a matter of sheer indifference, since one needs to monitor others at a distance to avoid contact with them when they are close, ranging from little maneuverings of sidewalk traffic to avoid physical collision, to averting eyes and controlling micro-gestures in order not to intrude into the privacy of their personal space.”

– Randall Collins, Interaction Ritual Chains, Princeton University Press, 2005, at p. 280. Citation removed, emphasis mine.

Waiting for builders and designers to provide good spaces for social and religious ritual is unlikely to be an effective strategy. What would it take for Americans to simply, impolitely use what space there is for these purposes? Americans flood the streets over sports team victories; I saw a crowd of young people pour into a busy street in Hollywood on the night the Obama victory was announced in 2008, out of pure tribal joy. The sustained occupations of public space in recent years (e.g. Occupy Wall Street) have been ugly and unsustainable, but demonstrate a willingness to break through politeness to use public space in new ways. Rather than permanent squatting, imagine a beautiful, rhythmic occupation, one of weekly repetition, of mass praying in the streets with no political goals at all.

This piece was first published by Front Porch Republic.

Sarah Perry studied urban planning at MIT and is a housewife in San Antonio, Texas. She is currently a guest blogger-in-residence at Ribbonfarm.

Trinity Church in Manhattan photo by Wikimedia Commons user Griffindor.