Global cities are like that famous quip on obscenity: we know one when we see it. But the definitions of global cities are incredibly varied and there doesn’t seem to be a consensus or well-defined way to think about. I looked at the criteria used in various prominent studies back in 2012 and found them highly divergent. Only the Sassen based one appeared to have a robust definition and theoretical basis, but it’s a pretty narrow definition. While it’s very important and useful, I don’t think it fully captures what the average person or urbanist thinks of on the topic.

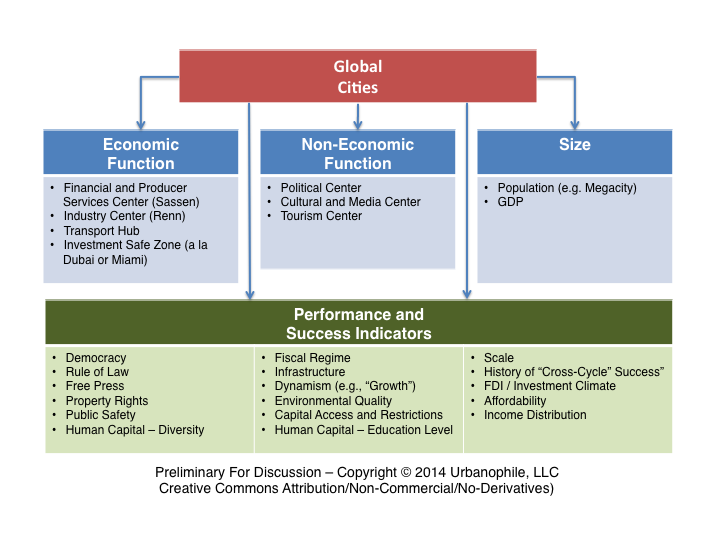

In wrestling with the global city idea while working on the global city study I did some research for, I put together this framework to help organize our thinking.

This framework seeks to capture in a structured manner all the ways people talk about global cities that I’m aware of.

There are three basic categories of criteria people use in defining global cities: economic function, non-economic function, and size.

Economic Function

Some, like Sassen, define global cities by economic function. In her case, just being a financial center isn’t enough. You need to be producing financial services products specifically related to the global economy, not just making mortgages domestically. I list “Financial and Producer Services Center” as a shorthand for this. In all of these definitions, when I say a “center” I’m referring to a center of global or regional (e.g., European or Latin American) significance, not simply a domestic center.

If I have a contribution to the global city definition genre, it’s my contention that places like the Bay Area (tech) or Paris (fashion and luxury) that are important global or regional epicenters of an important 21st century macroindustry are also global cities in a powerful sense by virtue of that.

The idea of being a transport hub for goods or services is self-explanatory, though I’ll note that simply being a goods distribution hub (such as a global air freight hub like Memphis) doesn’t necessarily imply a high value, high wage economy.

Lastly, and perhaps this is one I made some contributions to as well, is the idea of a “safe zone” for investing or parking capital. Much of the world is volatile economically and only has a dubious attachment to the rule of law and property rights. Hence wealthy people in those countries like to stash their cash in places where they consider it safe. Where I would distinguish this from a simple offshore account as in the Caymans is that this investment often includes real estate, and the rich folks in question often establish a personal base there. New York and London as the paradigmatic global cities obviously fall into this category, but I’m more thinking of regional hubs like Dubai, Miami, and Singapore. These places have established themselves as premier business (and in some cases cultural) hubs for their regions.

Non-Economic Functions

These are other aspects of a city’s function that I see as not directly economic, though obviously there are economic impacts. Most of these perhaps could be subsumed under being in an industry epicenter, but since global city surveys often call them out separately, I will as well.

The first item is being an important global political capital like Washington, Moscow or Beijing. Enough said.

Another important dimension is being a cultural and media center. Los Angeles profoundly affects the world because of its entertainment machine and the media that goes along with it. (By contrast, Mumbai may be a huge film center, but serves largely a domestic and Indian ethnic audience). Obviously the English language cities have a big advantage here in terms of media, though cities like Paris have a powerful cultural role.

Lastly, being a global tourism center is another dimension. Which places draw foreign visitors? You might want to read Nicole Gelinas’ recent taken on international tourism’s affect on New York. NYC attracts a third of all foreign visitors to the United States.

Size

Lastly, many surveys include measures that are purely about size, such as total GDP. The rhetoric about megacities (those with more than 10 million people) shows a fascination with size as well.

Success and Performance Indicators

Beyond the categories that define what global cities are, I include a horizontal layer talking about how to think about whether they are successful. I think there’s a big debate that can be had about whether these are performance indicators or selection criteria. Obviously more global city surveys want to pick highly performing cities, so these are part of their evaluation matrix. I myself originally included diversity and educational attainment (talent hub) on the non-economic function list.

I won’t go through these as they are pretty self-explanatory. I’d be interested to see where you all would put these, and what you’d add to or drop from the list.

By the way, in that global city survey I worked on, we decided to look purely at economic function, though pulling across media hub and treating that as an industry. We felt that taking this sort of view was a gap in the existing inventory of ratings, and also perhaps the most important way to think about global cities.

This is a concept in development, so please share your thoughts.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the founder of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile, where this piece originally appeared.

Hong Kong photo by BigStockphoto.com