A few years ago, the satirical publication, The Onion ran an article under the headline "98 Percent of US Commuters Favor Public Transit for Others." The spoof cited a mythical press release by the American Public Transit Association (APTA), in which Lance Holland of Anaheim, California said "Expanding mass transit isn’t just a good idea, it’s a necessity," Holland said. "My drive to work is unbelievable. I spend more than two hours stuck in 12 lanes of traffic. It’s about time somebody did something to get some of these other cars off the road." The Onion spoof said that APTA would be kicking off a new promotional campaign using the slogan "Take the Bus… I’ll be Glad You Did." The Onion spoof singled out Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) officials as saying that public support for mass transit will lead to its expansion and improvement."

"Transit for Others" characterizes three decades of transit in Los Angeles County. Despite its massive $10 billion plus rail program, MTA bus and rail services carried fewer riders in 2012 (latest Federal Transit Administration data) than were carried by the buses in 1985 (MTA was formed in the early 1990s from a merger between the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission and the Southern California Rapid Transit District).

The Birth of Modern Rail

The history of the modern Los Angeles rail revival began with a special meeting of the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission on August 20, 1980. I was to play a principal role.

I had the honor of being appointed to LACTC by Mayor Tom Bradley to three terms and was the only principal commissioner who was not an elected official. The other members, under state law, were the Mayor of Los Angeles, a Los Angeles City Council Member, the Mayor of Long Beach, two city council members from other cities, the five county supervisors and an additional member appointed by the Mayor of Los Angeles (which was me).

The special meeting had been requested by legendary county Supervisor Kenneth Hahn, who proposed a 5-year reduction of the bus fare to $0.50 to be financed by a sales tax increase, which would be submitted to the voters at the November election. Any money not needed for the bus fare reduction would be used for unspecified transit purposes.

The original motion by Supervisor Hahn was amended by Gardena Mayor Edmund Russ, who proposed a "local return program," which would dedicate 25 percent of the funding to municipalities (and Los Angeles County for unincorporated areas) on a population basis, to be used for transit services. At that time, local operators provided less than 20% of the bus service, with the overwhelming majority of services provided by the Southern California Rapid Transit District (SCRTD).

I was concerned that the proposal by Supervisor Hahn failed to provide funding for a rail system. I believed at the time that a rail system would reduce the intractable traffic congestion in Los Angeles. I was also concerned at the rapidly rising unit costs of bus operations and was convinced that unless there was a "firewall," no money would be available for rail.

As a result, on the spur of the moment, I introduced an amendment to direct 35 percent of the proceeds to rail. This motion was seconded by Supervisor Baxter Ward and was incorporated into the final package Supervisor Hahn accepted a shortening of the reduced fare period to three years. The measure, Proposition A was placed on the ballot and was passed by the voters in November.

Transit Since Proposition A

The impacts of the three programs approved in 1980 had varying results on transit in Los Angeles.

Three Year Fare Reduction (1982-1985): Between 1982 and 1985, there was a flat $0.50 fare for transit services in the county. SCRTD experienced an increase from 354 million to 497 million annual passengers. At 40%, this may be the largest three year relative increase in any large transit agency’s ridership in decades. Ridership fell after subsequent fare increases.

Further, the fare reduction was cost effective. The cost per new rider was less than $1.00 (2012$), a small fraction of typical projected costs per new riders on proposed rail transit systems around the country. By comparison, the cost per new rider on the east extension of the Gold light rail line was projected at more than $30 (2012$, $24.19 in 2003). This is more than 30 times the cost per new rider of the low fare program.

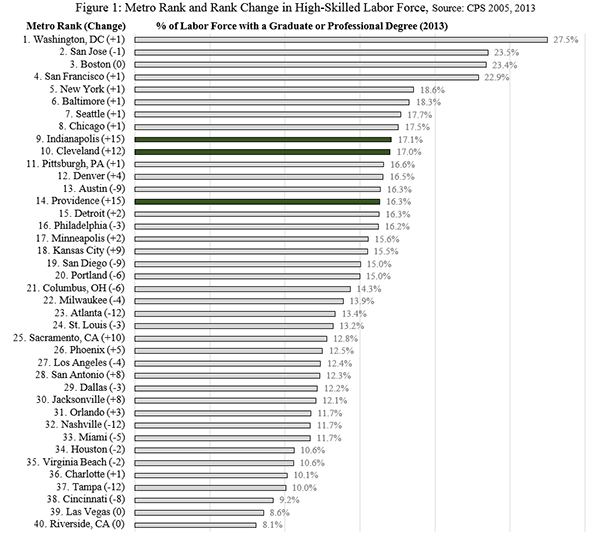

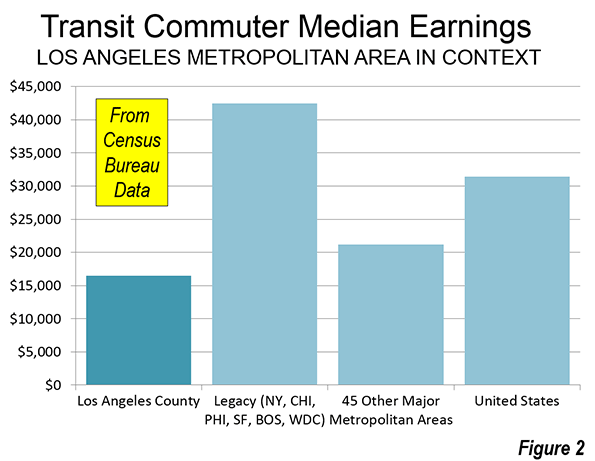

The strong ridership increase in response to the low fare program is consistent with the relatively low incomes of Los Angeles transit commuters. In 2013, the median income of Los Angeles County transit commuters was approximately one-half that of the national, 60 percent below that of the six metropolitan areas with transit legacy cities (New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Boston and Washington) and even lower than the other 45 metropolitan areas over 1,000,000 population (Figure 1)

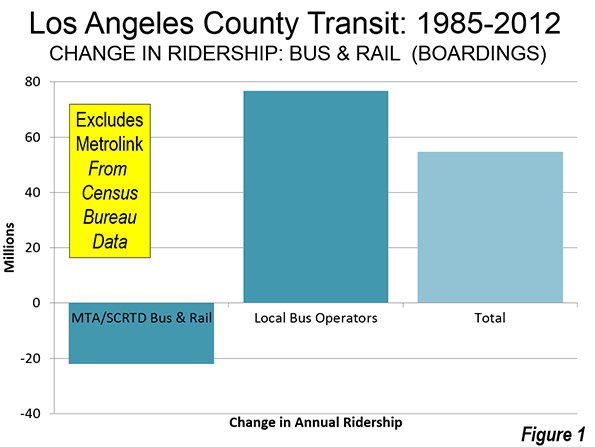

Local Return Program: Since 1985, when the bus fare reduction program ended, by far the greatest impact on ridership was from the Local Return program. In 1985, the existing local bus operators carried approximately 55 million annual passengers, a figure that rose to more than 130 million in 2012 (a nearly 140 percent increase). This ridership increase is more passengers that were carried on all the bus and rail systems of Dallas (DART), Salt Lake City and St. Louis in 2012, according to Federal Transit Administration data.

Urban Rail Program: Many miles of urban rail have been built in Los Angeles County, including two subways and five light rail lines (determined by route termini from downtown). But the hope that others would leave their cars for transit, as expressed in The Onion has not occurred. By 2012, Federal Transit Administration data indicates that MTA (formed by a merger of LACTC and the Southern California Rapid Transit District, which operated the system before) bus and rail system was carrying 475 million annual riders, down from the 497 million carried on buses alone in 1985.

This is despite constructing billions in subway lines, light rail lines, and rapid busways and the addition of approximately 2 million residents to Los Angeles County.

The "Return" on Local Return: The big surprise was the "return" on the local return program. A number of new systems were established, such as Foothill Transit and the Antelope Valley Transportation Authority. Many cities established new bus and paratransit systems. The city of Los Angeles now operates a number of commuter express bus services and local circulation bus services throughout the city. Many of the new systems used competitive tendering, under which services are awarded to competing private companies, with fares, routes, and schedules dictated by the public agencies. One important advantage of competitive tendering is lower costs, which makes it possible to provide more service. This service approach has been used extensively in Denver and San Diego. Further, virtually all of London’s largest public bus system in the high income world is competitively tendered as are all of the bus, subway, commuter rail and light rail services in Stockholm.

Overall, the Los Angeles County transit system, including MTA and the local operators experienced a ridership increase of 55 million between 1985 and 2012 (This excludes Metrolink, the five county commuter rail system established in the 1990s). Virtually all of the ridership increase is attributable to the local bus services operated by cities and by new sub-regional agencies (Figure 2).

Overall Transit Work Trip Share

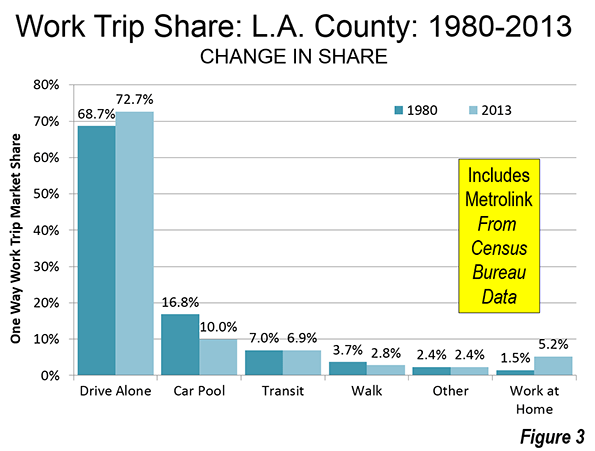

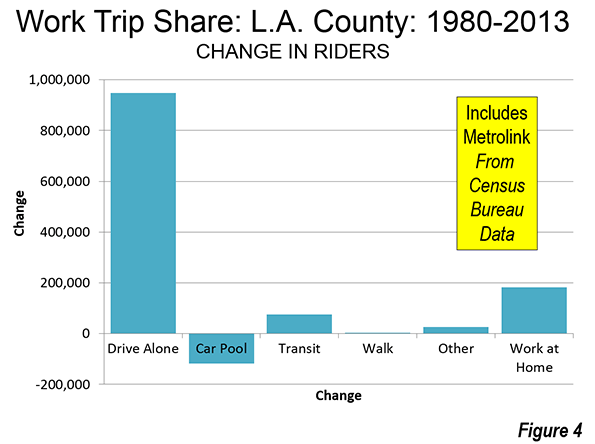

Census Bureau data indicates that the employment access share of transit in Los Angeles County has declined modestly, from 7.0 percent in 1980 to 6.9 percent in 2013 (including Metrolink). Driving alone increased from 68.7 percent to 72.7 percent, while car pool commuting dropped from 16.8 percent to 10.0 percent. Outside of driving alone, the largest increase occurred in working at home rising from 1.5 percent to 5.2 percent (Figure 3). Unlike transit, working at home requires virtually no expenditures of public funds. Transit one-way work trips increased 77,000 daily, while driving along increased 947,000 and working at home increased 182,000. Car pools suffered a large loss (Figure 4).

Thus, despite rave reviews about its rail system, Los Angeles relies on cars to an even greater extent than before. Los Angeles qualifies as the next great transit city only if the standard is spending and construction, rather than ridership.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He was appointed to the Amtrak Reform Council to fill the unexpired term of Governor Christine Todd Whitman and has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

—-

Note: Part of the MTA/SCRTD ridership loss was due to the transfer of services to Foothill Transit and the city of Los Angeles in the late 1980s.

Photo: Los Angeles County Transportation Commission logo from 1980s