There is an increasing recognition – at least outside the academy, planning organization and urban core developer groups – that the spatial expansion of cities or suburbanization represents the evolving urban form of not only the United States and virtually all of the high income world but also across the developing world, whether middle income or third world.

In recent years, Mexico has made substantial economic progress. Per capita income (purchasing power parity) in Mexico exceeds that of all the "BRIC" nations (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) except resource-rich Russia.

In Mexico, as almost everywhere, cities continue to expand to provide more living space for an emerging suburban middle-class. This is obvious in the new townhouse (attached house) and detached house developments that ring the urban areas (photograph above). Some of the best evidence of this can be observed on and beyond the southern edge of the nation’s second-largest urban area, Guadalajara (for example on Google Earth).

The Valley of Mexico

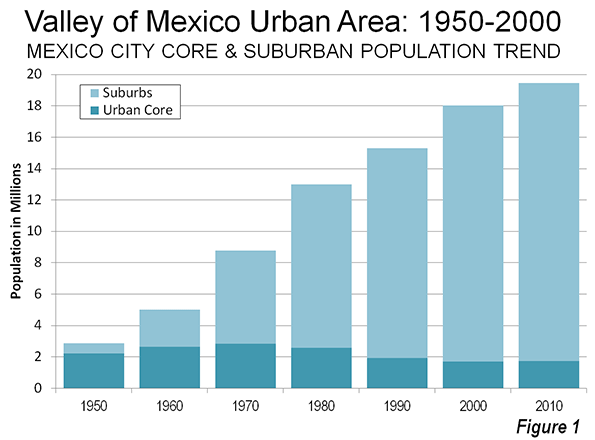

Nearly 3 years ago, one of the first Evolving Urban Form articles highlighted the Valley of Mexico metropolitan area, which is Mexico City in its functional (economic) manifestation. That article noted that the core municipality of Mexico City in 1950 had 2.23 million residents out of the urban area’s fewer than 3 million and comprised only 54 square miles (139 square kilometers). By 1970, the city’s population had risen to 2.85 million. However, as has happened in Paris, Copenhagen, Milan, Osaka, Glasgow, Detroit, and many others, the urban core population plummeted. By 2000, the former city had a population of only 1.69 million, a 40 percent loss from 1970. There was a modest population increase between the 2000 and 2010 censuses, but its population seems unlikely to ever be restored to near their previous peak, which mirrors the experience of Paris and Copenhagen.

Instead all population growth in the Valley of Mexico metropolitan area has been outside the 1950 area of Mexico City and in the post-World War II suburbs. While comparable metropolitan area data is not available, the Mexico City urban area added more than 10 million residents between 1970 and 2010. The same period, the suburban areas added more than 11 million residents (Figure 1). The Valley of Mexico metropolitan area is located not only in the Distrito Federal, but also in the states of Mexico and Hidalgo.

The Other Major Metropolitan Areas

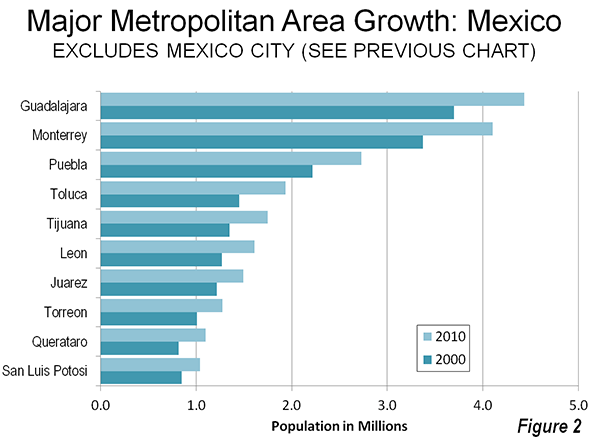

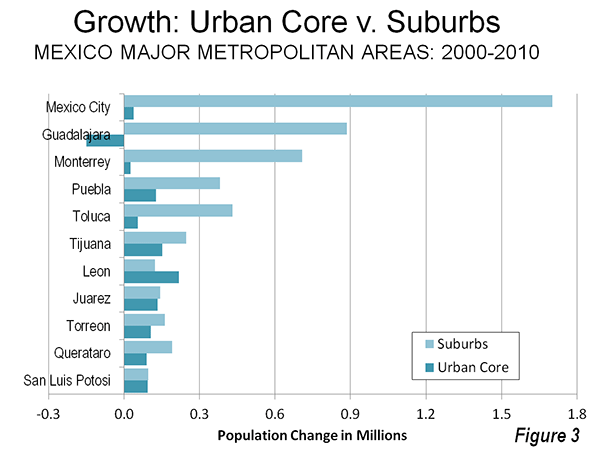

While the scale of urbanization in the Valley of Mexico dwarfs that of the rest of the nation, similar dispersion is evident in the nation’s other 11 metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 population (Figures 2 and 3).

Guadalajara

Guadalajara, capital of state of Jalisco, is Mexico’s second largest metropolitan area. Between 2000 and 2010, the metropolitan area grew nearly 20 per cent, from 3.7 million residents to 4.4 million. The core city (locality) of Guadalajara lost 150,000 residents, registering a population of just under 1.5 million in 2010. Suburbs accounted for approximately all the metropolitan area’s population growth.

Monterey

Monterey, capital of the state of Nuevo Leon, is currently the third largest metropolitan area in Mexico and is growing slightly more rapidly than Guadalajara. Between 2000 and 2010, Monterey added 22 per cent to its population, which increased from 3.4 million residents to 4.1 million. The central locality grew modestly, but 97 per cent of the metropolitan area growth was in the suburbs.

Central Mexico

The Valley of Mexico metropolitan area is encircled by smaller, but major metropolitan areas that are among the fastest-growing in the nation.

Queretaro, the capital of the state of Queretaro, is located 130 miles (220 kilometers) north of Mexico City by freeway. Queretaro is the fastest-growing major metropolitan area in Mexico, having added 34 per cent to its population over the last census period, to reach 1.1 million. More than two thirds of the growth was in the suburbs.

Toluca, capital of the state of Mexico (Note), is located across a mountain range only 40 miles (65 kilometers) west of Mexico City. Toluca grew 33 percent to 1.9 million residents in 2010. Nearly 90 per cent of Toluca’s population growth was in the suburbs between 2000 and 2010.

Pueblo, capital of the state of Puebla, is located across mountain range 130 miles (80 kilometers) to the east of Mexico City. Puebla is located in a valley surrounded by some of the most spectacular volcanoes in the world, including Popocateptl and Iztaccihuatl (both more than 17,000 feet, or 5,100 meters), toward Mexico City, La Malinche (14,600 feet or 4,500 meters), only 17 miles from the city center and Orizaba (18,500 feet or 5,600 meters). The three tallest of these reach elevations higher than any in North America outside of the Yukon and Alaska. Puebla was the slowest growing of the Central Mexico metropolitan areas, adding 23 percent to its population, and reaching 2.9 million residents in 2010. Three quarters of Puebla’s growth was in the suburbs. The Puebla metropolitan area extends into the state of Tlaxcala.

Border Metropolitan Areas

In comparison, the large metropolitan areas on the United States border expanded outwards but not as rapidly. Tijuana, which is adjacent to the San Diego metropolitan area now has 1.75 million residents. More than 60 percent of its growth over the preceding 10 years was suburban. Juarez (located in the state of Chihuahua), is across the border from the El Paso metropolitan area and reached a population of 1.5 million, with slightly more than one half of its growth being in the suburbs. Neither San Diego-Tijuana area nor Juarez -El Paso qualify as metropolitan areas because they are not labor markets – there are significant limitations on the movement of labor (employees).

Other Interior Metropolitan Areas

Three other major metropolitan areas are located in the interior. In Torreon (states of Coahuila and Durango), more than 60 percent of the population growth was in the suburbs. A smaller 51 percent of the growth in San Luis Potosi (state of San Luis Potosi) was in the suburbs. The significant exception was Leon (state of Guanajuato), where only 36 percent of the growth was outside the core urban core.

Continuing Dispersion

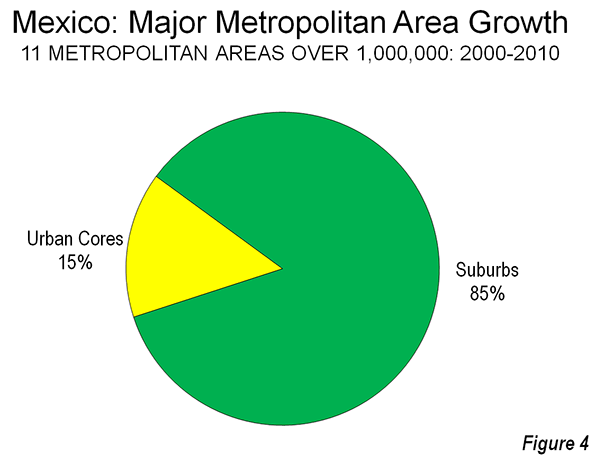

Overall, 5.1 million of the 6.0 residents added to Mexico’s major metropolitan areas between 2000 and 2010 were outside the urban cores (Figure 4). Most of the growth was in the three largest metropolitan areas (Mexico City, Guadalajara and Monterrey), which added 3.2 million residents. The urban cores of these three metropolitan areas together declined approximately 100,000, while the suburbs attracted more than all of the metropolitan area growth. Mexico seems well positioned for continued economic growth and a populace that seeks better standards of living, more often than not in dispersed settings.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

—————-

Note: The state of Mexico has the largest population in the nation, at 15.2 million (2010). This is 70 percent more than the second largest federal division, the Distrito Federal. This state of Mexico borders the Distrito Federal (Mexico City) on three sides and it outer suburban areas constitute more than one-half of the Valley of Mexico metropolitan area population (11 million of 21 million). Another 2 million are located in the even more distant state of Hidalgo. This state of Mexico also includes Toluca, another major metropolitan area (see above).

————

Photograph: Southern suburbs of Guadalajara (by author)

Correction: This version removes reference to Tijuana as the capital of Baja California. Mexicali is the state capital.