The recent decision by Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Allan J. Goodman to reject as “fatally flawed” the densification plans for downtown Hollywood could shake the foundations of California’s “smart growth” planning clerisy. By dismissing Los Angeles’ Hollywood plan, the judge also assaulted the logic behind plans throughout the region to construct substantial high-rise development in “transit-oriented developments” adjacent to rail stations.

In particular, the judge excoriated the buoyant population-growth projections used to justify the plan, a rationalization for major densification elsewhere in the state. The mythology is that people are still flocking to Los Angeles, and particularly, to dense urban areas, creating a demand for high-end, high-rise housing.

The Hollywood plan rested on city estimates provided by the Southern California Association of Governments, which estimated that Hollywood’s population was 200,000 in 2000 and 224,000 in 2005, and would thus rise to 250,000 by 2030. All this despite the fact that, according to the census, Hollywood’s population over the past decade has actually declined, from 213,000 in 1990 to 198,000 today. Not one to mince words, Judge Goodman described SCAG’s estimates as “entirely discredited.”

This discrepancy is not just a problem in the case of Hollywood; SCAG has been producing fanciful figures for years. In 1993, SCAG projected that the city of Los Angeles would reach a population of 4.3 million by 2010. SCAG’s predicted increase of more than 800,000 residents materialized as a little more than 300,000. For the entire region, the 2008 estimates were off by an astounding 1.4 million people.

Similar erroneous estimates run through the state planning process. In 2007, California’s official population projection agency, the Department of Finance, forecast that Los Angeles County would reach 10.5 million residents in just three years. But the 2010 U.S. Census counted 9.8 million residents.

Such inflated estimates, however, do serve as the basis for pushing through densification strategies favored by planners and their developer allies. In fact, SCAG’s brethren at the Association of Bay Area Governments, seeking to justify their ultradense development plan, recently went beyond even population estimates issued by the Department of Finance.

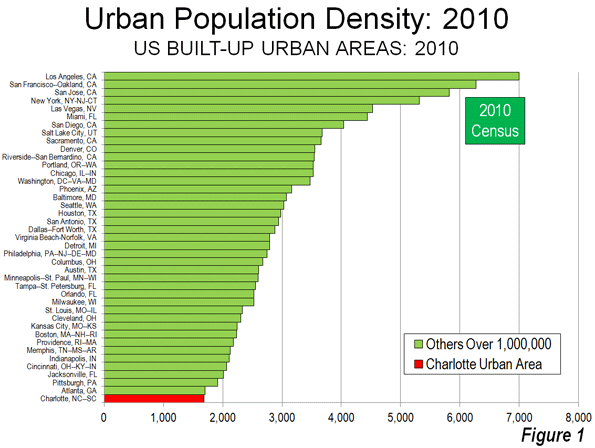

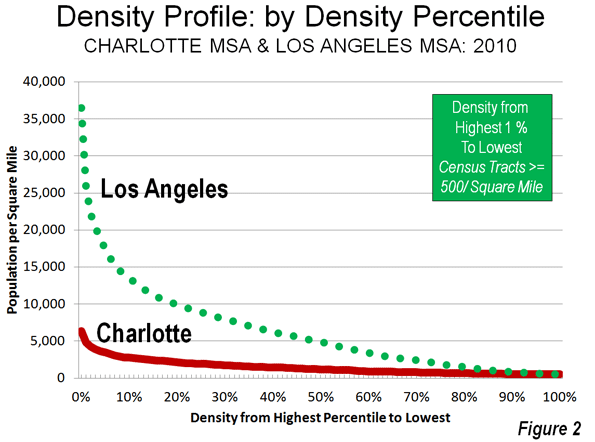

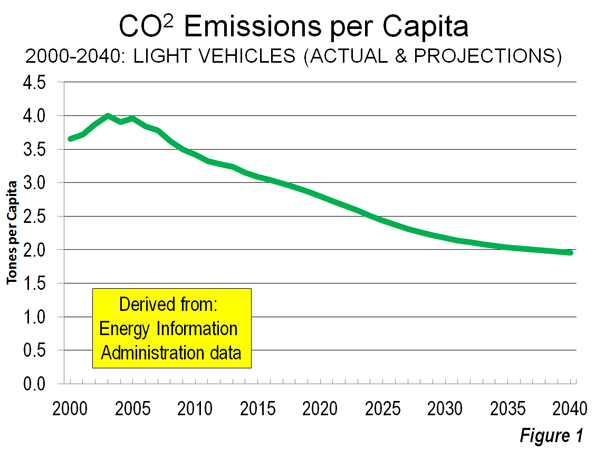

The problem here is not that some developers may lose money on projects for which there is inadequate demand, but that this densification approach has replaced business development as an economic strategy. Equally bad, these policies often threaten the character of classic, already-dense urban neighborhoods, like Hollywood. Indeed, the Los Angeles urban area is already the densest in the United States, and a major increase in density is sure to further worsen congestion.

Not surprisingly, some 40 neighborhood associations and six neighborhood councils organized against the city’s Hollywood plan. Their case against the preoccupation with “transit-oriented development” rests solidly on historical patterns. Unlike in New York City, much of which was built primarily before the automobile age, Los Angeles has remained a car-dominated city, with roughly one-fifth Gotham’s level of mass-transit use. Despite $8 billion invested in rail lines the past two decades, there has been no significant increase in L.A.’s transit ridership share since before the rail expansion began.

The Hollywood plan is part of yet another effort to reshape Los Angeles into a West Coast version of New York, replacing a largely low-rise environment with something former Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa liked to call “elegant density.” As a councilman, new Mayor Eric Garcetti proclaimed a high-rise Hollywood as “a template for a new Los Angeles,” even if many Angelenos, as evidenced by the opposition of the neighborhood councils, seem less than thrilled with the prospect.

If the “smart growth” advocates get their way, Hollywood’s predicament will become a citywide, even regional, norm. The city has unveiled plans to strip many single-family districts of their present zoning status, as part of “a wholesale revision” of the city’s planning code. Newly proposed regulations may allow construction of rental units in what are now back yards and high-density housing close to what are now quiet residential neighborhoods.

“They want to turn this into something like East Germany; it has nothing to do with the market,” suggests Richard Abrams, a 40-year resident of Hollywood and a leader of Savehollywood.org. “This is all part of an attempt to worsen the quality of life – to leave us without back yards and with monumental traffic.”

Of course, it is easy to dismiss community groups as NIMBYs, particularly when it’s not your neighborhood being affected. But here, the economics, too, make little sense. New, massive “luxury” high-rise residential buildings were not a material factor in the huge density increases that made the Los Angeles urban area more dense than anywhere else in the nation during the second half of the 20th century. Even in New York City, the high-rise residential buildings where the most affluent live are concentrated in the lower half of Manhattan; they house not even 20 percent of the city’s population.

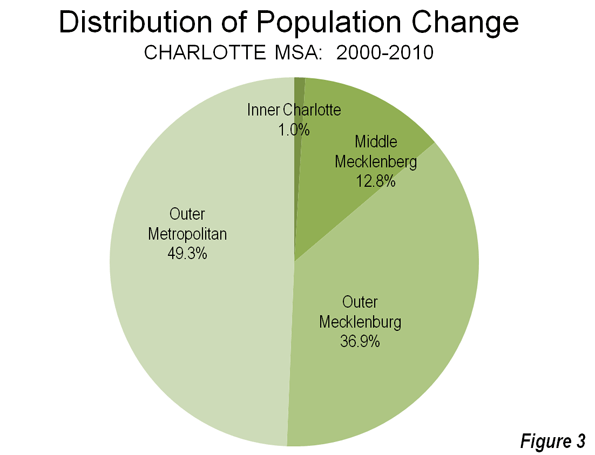

Under any circumstances, the era of rapid growth is well behind us. In the 1980s, the population of Los Angeles grew by 18 percent; in the past decade, growth was only one-fifth as high. Growth in the core areas, including downtown, overall was barely 0.7 percent, while the population continued to expand more rapidly on the city’s periphery. Overall, the city of Los Angeles grew during the past decade at one-third the national rate. This stems both from sustained domestic outmigration losses of 1.1 million in Los Angeles County and immigration rates that have fallen from roughly 70,000 annually in the previous decade to 40,000 a year at present.

Nor can L.A. expect much of a huge infusion of the urban young talent, a cohort said to prefer high-density locales. In a recent study of demographic trends since 2007, L.A. ranked 31st as a place for people aged 20-34, behind such hot spots as Milwaukee, Oklahoma City and Philadelphia. It does even worse, 47th among metro areas, with people ages 35-49, the group with the highest earnings.

In reality, there is no crying need for more ultradense luxury housing – what this area needs more is housing for its huge poor and working-class populations. More important, we should look, instead, at why our demographics are sagging so badly. The answer here, to borrow the famous Clinton campaign slogan: It’s the economy, stupid. In contrast with areas like Houston, where dense development is flourishing along with that on the city’s periphery, Southern California consistently lands near the bottom of the list for GDP, income and job growth, barely above places like Detroit, Cleveland or, for that matter, Las Vegas.

Despite many assertions to the contrary, densification alone does not solve these fundamental problems. The heavily subsidized resurgence of downtown Los Angeles, for example, has hardly stemmed the region’s relative decline.

Instead of pushing dense housing as an economic panacea, perhaps Mayor Garcetti should focus on why the regional economy is steadily falling so far behind other parts of the nation. One place to start that examination would be with removing the regulatory restraints that chase potential jobs and businesses – particularly better-paying, middle class ones – out of the region. It should also reconsider how the “smart growth” planning policies have helped increase the price of housing, particularly for single-family homes, preferred by most families.

At the same time, the mayor and other regional leaders should realize that L.A.’s revival depends on retaining the very attributes – trees, low-rise density, sunshine, as well as entrepreneurial opportunity – that long have attracted people. People generally do not migrate to Los Angeles to live as they would in New York or Chicago. Indeed, Illinois’ Cook County (Chicago) and three New York City boroughs – Manhattan, Queens and Brooklyn – are among the few areas from which L.A. County is gaining population. Where are Angelinos headed? To relatively lower-density places, such as Riverside-San Bernardino, Phoenix and Houston.

Under these circumstances, pushing for more luxury high-rises seems akin to creating structures for which there is little discernible market. Once demographic and economic growth has been restored broadly, it is possible that a stronger demand for higher-density housing may emerge naturally. Until then, the higher density associated with “smart growth” neither addresses our fundamental problems, nor turns out to be very smart at all.

This story originally appeared at The Orange County Register.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.