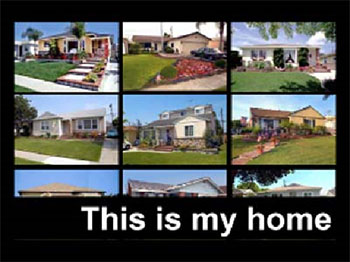

Where I live is where most Californians live: in a tract house on a block of more tract houses in a neighborhood hardly distinguishable from the next, and all of these houses extending as far as the street grid allows.

My exact place on the grid is at the southeast corner of Los Angeles County, between the Los Angeles and San Gabriel rivers. But my place could be almost anywhere in the suburbs of Los Angeles and Orange counties.

My suburb may seem characterless, but it has a complex history of working class aspiration, of assumptions about social hygiene, of urban politics, and the decisions of many who imposed their imagination on the landscape.

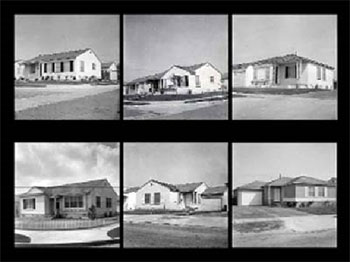

Where I live is a tract of wood-framed houses on a 5,000-square-foot lot at a density of about seven units per acre, where houses are set back 20 feet from the sidewalk and a street tree the city trims, and where neighborhood businesses are clustered at intersections so that anyone can walk to the store or a bar or to a fast food place.

It’s also a place with 10 parks of 20 or more acres each so that everyone is about a mile from supervised open space with playgrounds, ball diamonds, picnic tables, and bar-b-cues.

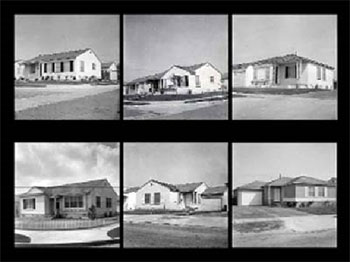

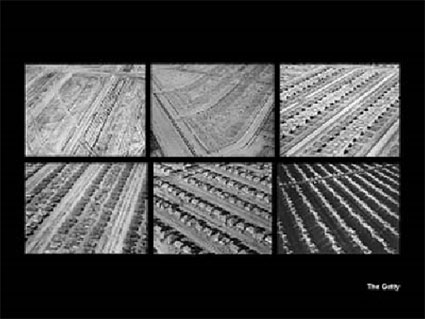

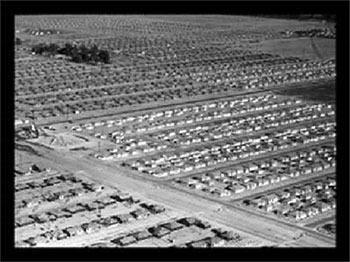

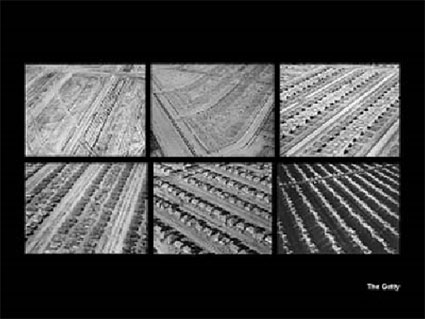

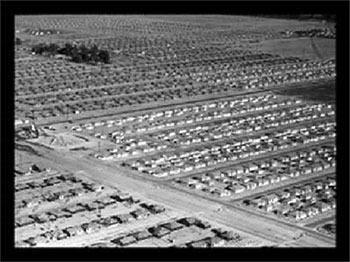

There is a persistent belief that suburban places like mine must be awful places they must be inhuman and soul-destroying places. That belief persists partly because of these photographs, taken by a brilliant young aerial photographer named William Garnett who worked for the developers of Lakewood between 1950 and 1952.

There is a persistent belief that suburban places like mine must be awful places they must be inhuman and soul-destroying places. That belief persists partly because of these photographs, taken by a brilliant young aerial photographer named William Garnett who worked for the developers of Lakewood between 1950 and 1952.

The historian and social critic Lewis Mumford used Garnett’s photographs in 1961 to indict the post-war suburbs which, he said, had become “A multitude of uniform unidentifiable houses, lined up inflexibly at uniform distances on uniform roads, in a treeless command waste inhabited by people of the same class, the same incomes, the same age group, witnessing the same television performances, eating the same tasteless prefabricated foods, from the same freezers … .Thus the ultimate effect of the suburban escape in our time is, ironically, a low grade uniform environment from which escape is impossible.”

The architectural historian Peter Blake used these photographs in 1964 to define the post-war suburbs as “God’s own junkyard.”

In 1969, Garnett’s photographs were part of Nathaniel Owings’s The American Aesthetic, a passionate critique of 20th century urban planning.

Today, you can go to the Getty Museum in Brentwood and the Autry National Center in Los Angeles and see these photographs used as defining images of the suburbs of Los Angeles.

They are beautiful and terrible photographs.

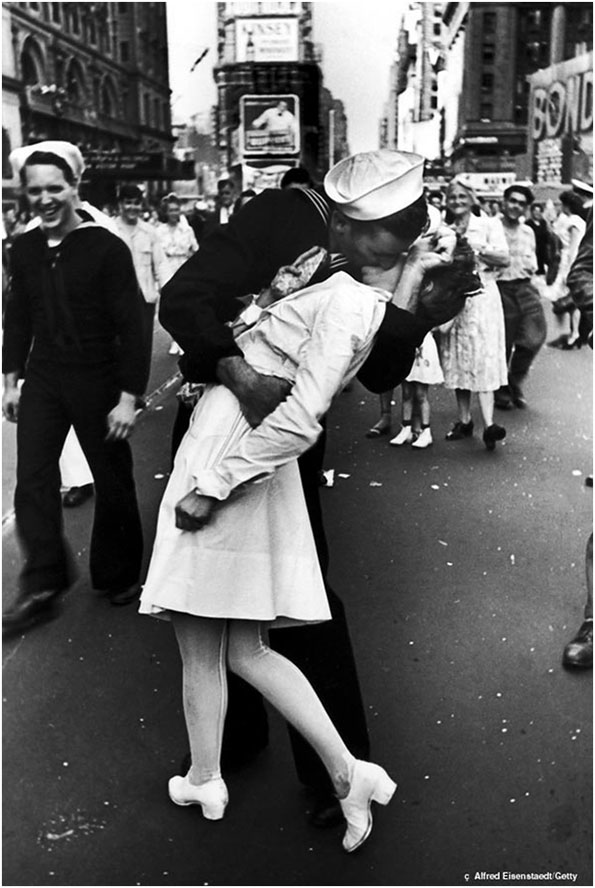

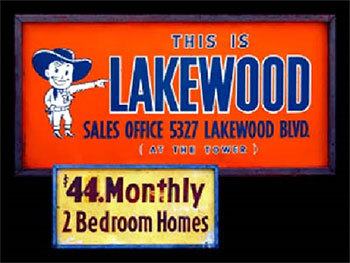

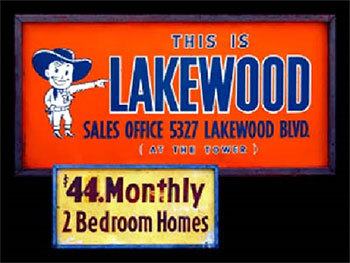

With no little irony, these images of Lakewood became emblematic of the suburbs at the moment when Lakewood no longer was the eerie and empty place Garnett had photographed only a few months before. Between 1950 and 1953 – in less than 33 months – 17,000 houses had been built, sold, and made someone’s home. Nearly 100,000 people lived there, including my parents. In 1954, Lakewood had even become a city in the political sense, having completed the first municipal incorporation in California since 1939.

Listen to Lakewood Blvd by Sara Lindsay

We can presume that the developers of Lakewood – Mark Taper, Ben Weingart, and Louis Boyar – saw Garnett’s photographs mostly as a record to be filed with work logs and construction accounts when the project ended. But I also imagine that they looked at Garnett’s photographs and read into them a grandeur, a collective heroism that still attaches itself to the great construction projects of the 1930s and 1940s.

And we know that Boyer, Taper, and Weingart and Fritz Burns and Joseph Eichler and Henry Kaiser understood that the Progressive era model of low-cost housing they had adapted to mass production would result in new relationships to the idea of place. Garnett’s photographs of deeply shadowed forms on a titanic grid would for some critics and many Americans permanently define that relationship as dread.

And we know that Boyer, Taper, and Weingart and Fritz Burns and Joseph Eichler and Henry Kaiser understood that the Progressive era model of low-cost housing they had adapted to mass production would result in new relationships to the idea of place. Garnett’s photographs of deeply shadowed forms on a titanic grid would for some critics and many Americans permanently define that relationship as dread.

In a memorable speech by James Howard Kunstler at the 1999 Congress for the New Urbanism, the kind of place where I live was described as a perversion of a place. “It is the dwelling place of untruth,” Kunstler told the New Urbanists. The title of his speech was “The place where evil dwells.”

My parents and their neighbors more generously than Mumford or Blake or Kunstler understood what they had gained and lost in owning a small house on a small lot in a neighborhood connected to square miles of just the same.

Despite everything that was mistaken or squandered in making my suburb, I believe a kind of dignity was gained. More men than just my father have said to me that living in my kind of place gave them a life made whole and habits that did not make them feel ashamed.

Despite everything that was mistaken or squandered in making my suburb, I believe a kind of dignity was gained. More men than just my father have said to me that living in my kind of place gave them a life made whole and habits that did not make them feel ashamed.

As far as I could tell by their lives, my parents did not escape to their mass-produced suburb. They never considered escaping from it. Nor have I.

I’ve lived my whole life in the 957-square-foot house my parents bought when the suburbs were new, when no one could guess what would happen after tens of thousands of working-class husbands and wives – so young and so inexperienced – were thrown together without an instruction manual and expected to make a fit place to live.

What happened after was the usual redemptive mix of joy and tragedy.

The suburb where I live is a place that once mass-produced a redemptive future for displaced Okies and Arkies, Jews who knew the pain of exclusion, Catholics who thought they did, and anyone white with a job. Left out were many tens of thousands of others: people of color whose exclusion was not just a Californian transgression.

Today, futures still begin here, except the anxious, hopeful people who seek them are as mixed in their colors and ethnicities as all of southern California.

I continue to live in Lakewood with anticipation because I want to find out what happens next to new narrators of suburban stories who happen to be my Latino, black, Filipino, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese neighbors.

There are Californians who don’t regard a tract house as a place of pilgrimage, but my parents and their friends did. They were grateful for the comforts of their not-quite-middle-class life. Their aspiration wasn’t for more but only for enough despite the claims of critics then and now who assume that suburban places are about excess.

There are Californians who don’t regard a tract house as a place of pilgrimage, but my parents and their friends did. They were grateful for the comforts of their not-quite-middle-class life. Their aspiration wasn’t for more but only for enough despite the claims of critics then and now who assume that suburban places are about excess.

I actually believe that the place where I live is, in words of the Californian philosopher Josiah Royce, a “beloved community.” The strength of that regard, Royce thought, might be enough to form what he called an “intentional community” – a community of shared loyalties – even if the community is as synthetic as a tract-house suburb or the Gold Rush towns that Royce knew in his boyhood. I believe Royce was right: At a minimum, loyalty to the idea of loyalty is necessary, even if the objects of our loyalty are uncertain.

Urban planners tell me that my neighborhood was supposed to have been bulldozed away years ago to make room for something better, and yet the houses on my block stubbornly resist, loyal to an idea of how a working-class neighborhood should be made.

It’s an incomplete idea even in Lakewood, but it’s still enough to bring out 400 park league coaches in the fall and 600 volunteers to clean up the weedy yards of the frail and disabled on Volunteer Day in April and over 2,000 residents to sprawl on lawn chairs and blankets to listen to the summer concerts in the park.

I don’t live in a tear down neighborhood, but one that makes some effort to build itself up. All this is harder now, for reasons we all know.

The suburbs aren’t all alike, of course, and there are plenty of toxic places to live in gated enclaves and McMansion wastelands. Places like that have too much – too much isolation and mere square footage – but, paradoxically, not enough. Specifically, they don’t have enough of the play between life in public and life in private that I see choreographed by the design of my suburb.

With neighbors just 15 feet apart, we’re easily in each other’s lives – across fences, in front yards, and even through the thin, stucco-over-chicken-wire of house walls. When I walk out my front door, I see the human-scale, porous, and specific landscape into which was poured all the ordinariness that has shaped my work, my beliefs, and my aspirations. Out there, I renew my “sense of place” and my conviction that a “sense of place,” like a “sense of self,” is part of the equipment of a conscious mind.

We often find it difficult to talk coherently about these issues or to make coherent policy choices for places to which our loyalty is only lightly attached.

It seems to me that the abiding problem of southern California indeed of the entire West is the problem of home. We long for a home here, but doubt its worth when we have it. We depend on a place to sustain us, but dislike the claims on us that places make. Each of us is certain about our own preference for a place to live, but we’re always ready to question your choice.

How do we make our home here, in new and sudden and places like Lakewood, like Irvine, like Santa Clarita? We’ve been asking that question for a very long time sometimes in despair. At almost the beginning of California, a disillusioned 49er named Thomas Swain wrote in 1851, “Large cities have sprung into existence almost in a day. . . The people have been to each other as strangers in a strange land ….”

And too many of us are strangers still in a place that too many regard as uniquely perverse. And because much of southern California looks roughly the same too many of us see all these suburban places as aesthetically, politically, and morally perverse as well. And no place – however well crafted – is immune from the peculiarly American certainty that something better – something more adequate to the demands of our desire – is just beyond the next bend in the road.

The question of “home” is increasingly acute because there’s hardly anywhere left to build another Lakewood or Irvine or Santa Clarita.

The closing of the suburban frontier in southern California ends a 100-year experiment in place making on an almost unimaginable scale. The experiment was based on a remarkably durable consensus about the way ordinary people ought to be housed, beginning with turn-of-the-century beliefs about the power of a “home in its garden” to ameliorate the lives of working people and ending in the 1950s with tract houses turned into an affordable commodity.

Today, most of southern California is what it will continue to be: uniformly dense and multi-polar, urbanized in fact but suburban in appearance, characterized by single-family homes in neighborhoods with a strong – but provisional – dependence on more “urban-like” nodes.

This is a form for living and working, but it is neither “incoherent” nor “mindless sprawl.” That form in the future will, of course, be somewhat more dense – but our evolving suburbs cannot deliver mere density. In tandem with greater concentration of housing types must come what working-class people have always sought in southern California: a home with enough private space around it and enough public space adjacent to it so that this assemblage of house, lot, street, and transportation grid form the neighborhood-specific space that answers our desires.

We can lament that too many suburban places are less than they some wish them to be, but I see no perfect way to bring “utopias” out of these suburban habits both good and bad. I see only a persistent longing to make fit places in which to live.

Many of these places will look an awful lot like Orange County – dispersed, uniformly dense, and embedded in a metropolitan region in which historic downtowns function as “nodes.” The contest for the soul of our suburban region hinges on whether this constitutes enough to make a place where memories might be unblighted and desires assuaged.

The author and environmentalist Barry Lopez considered some years ago what might be needed to make a durable life for ourselves in southern California. And in considering the problem of home, Lopez asked a challenging question: “How can we become vulnerable to the place where we live?”

If that might be a goal if that tenderness were possible we might ask different questions when we build or approve a development project. We could ask, "What aspects of its design encourage loyalty to this place? What is built into this place that might evoke someone’s sympathy? Would anyone ever become vulnerable to this place?”

What I have been speaking of is the acquisition something more than an idiosyncratic sensibility but a communal achievement that requires something from all of us. Built-out, maximally diverse, and more grown up, southern California requires courage to extend one’s imagination across its whole, tragic, human, and humanizing body.

As for me, my suburb’s modesty keeps me there. When I stand at the head of my block, I see a pattern of sidewalk, driveway, and lawn, set between parallel low walls of house fronts that aspires to be no more than harmless. We live in a time of great harm to the ordinary parts of our lives and I wish that I had acquired all the resistance that my neighborhood offers.

What I hope we might gain is a larger “moral imagination” … the imagination by which we might write ourselves into the story of our place and negotiate a way from the purely personal to the public.

I don’t really know how (or perhaps I do only dimly). But faithfulness to what can be found in our history – to what can be found in our shared stories – impels me forward.

It may surprise you to learn the object of Lopez’s meditation on vulnerability was the place where he grew up – a tract house neighborhood in the San Fernando Valley. And Lopez had this additional insight while contemplating his Valley home. He wrote . . . “Always when I return there, I have found again the ground that propels me past the great temptation of our time to put one’s faith in despair.”

Despair or regret: “There once was a perfect Eden,” the conventional story goes, “to which gullible people were lured and as a result this Edenic place declined into the horrors of suburbanization.” And the moral of that story is “people ruin places.”

I believe that people and places form each other … the touch of one returning the touch of the other. What we seek, I think, is tenderness in this encounter, but that goes both ways, too. I believe that places acquire their sacredness through this giving and taking. And with that ever-returning touch, we acquire something sacred from the place where we live. What we acquire, of course, is a home.

It’s a question of falling in love … falling in love with the place where you are; even a place like mine … so ordinary, so commonplace, and my home.

# # #

D. J. Waldie is a contributing editor at the Los Angeles Times and a contributing writer for Los Angeles magazine. He is the author most recently of California Romantica with Diane Keaton. He blogs for KCET TV at http://www.kcet.org/user/profile/djwaldie.

There is a persistent belief that suburban places like mine must be awful places they must be inhuman and soul-destroying places. That belief persists partly because of these photographs, taken by a brilliant young aerial photographer named William Garnett who worked for the developers of Lakewood between 1950 and 1952.

There is a persistent belief that suburban places like mine must be awful places they must be inhuman and soul-destroying places. That belief persists partly because of these photographs, taken by a brilliant young aerial photographer named William Garnett who worked for the developers of Lakewood between 1950 and 1952.

And we know that Boyer, Taper, and Weingart and Fritz Burns and Joseph Eichler and Henry Kaiser understood that the Progressive era model of low-cost housing they had adapted to mass production would result in new relationships to the idea of place. Garnett’s photographs of deeply shadowed forms on a titanic grid would for some critics and many Americans permanently define that relationship as dread.

And we know that Boyer, Taper, and Weingart and Fritz Burns and Joseph Eichler and Henry Kaiser understood that the Progressive era model of low-cost housing they had adapted to mass production would result in new relationships to the idea of place. Garnett’s photographs of deeply shadowed forms on a titanic grid would for some critics and many Americans permanently define that relationship as dread. Despite everything that was mistaken or squandered in making my suburb, I believe a kind of dignity was gained. More men than just my father have said to me that living in my kind of place gave them a life made whole and habits that did not make them feel ashamed.

Despite everything that was mistaken or squandered in making my suburb, I believe a kind of dignity was gained. More men than just my father have said to me that living in my kind of place gave them a life made whole and habits that did not make them feel ashamed.

There are Californians who don’t regard a tract house as a place of pilgrimage, but my parents and their friends did. They were grateful for the comforts of their not-quite-middle-class life. Their aspiration wasn’t for more but only for enough despite the claims of critics then and now who assume that suburban places are about excess.

There are Californians who don’t regard a tract house as a place of pilgrimage, but my parents and their friends did. They were grateful for the comforts of their not-quite-middle-class life. Their aspiration wasn’t for more but only for enough despite the claims of critics then and now who assume that suburban places are about excess.