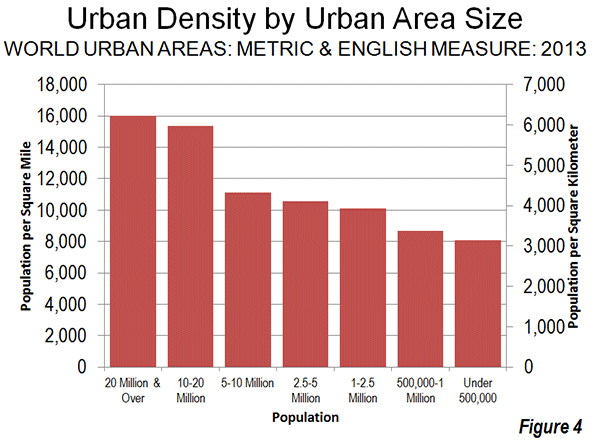

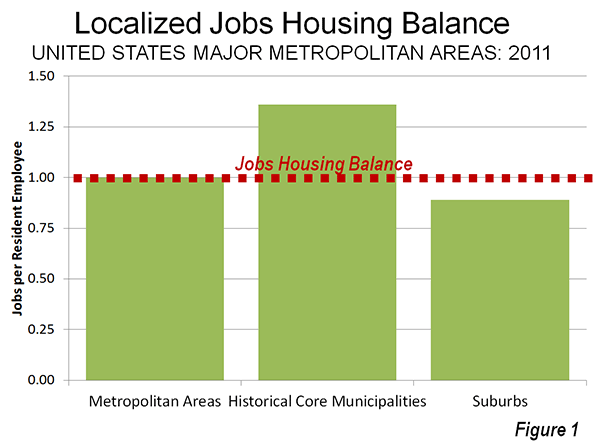

Suburban areas in the US metropolitan areas with more than 1 million total regional population, once largely seen as bedroom communities, are nearing parity between jobs and resident employees. The jobs housing balance, which measures the number of jobs per resident employee in a geographical area has reached 0.89 (jobs per resident workers) in these 51 major metropolitan areas, according to data in the 2011 one-year American Community Survey. This is well below the 1.39 ratio of jobs to resident employees in the historical core municipalities (Figure 1).

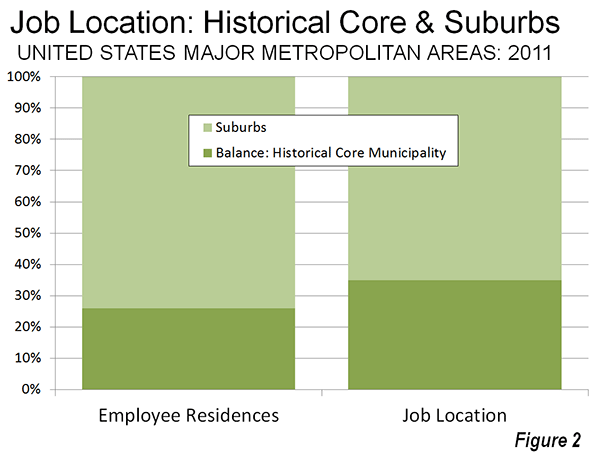

The historical core municipalities still have a larger share of metropolitan employment than they have of resident workers. However, 65 percent of major metropolitan area jobs are now in the suburbs, where 74 percent of workers live (Figure 2). The 0.89 jobs housing balance index indicates that there are only 11 percent fewer jobs in the suburbs than resident workers. Overall, the jobs housing balance of metropolitan areas (a synonym for labor markets) is at or near 1.00.

From Monocentric to Polycentric to Dispersed Cities

The data indicates the extent to which the classical monocentric city has been left behind by the evolution of the modern metropolitan area. Before the near universal extension of automobile ownership, cities were necessarily much more monocentric. Transit lines tended to converge on downtown, which made downtowns far more dominant in their share of metropolitan employment than they are today.

For example, in 1926, according to historian Robert M. Fogelson writing in Downtown: Its Rise and Fall: 1880-1950, in 1926 41 percent of Los Angeles residents went to downtown every day, a figure that had dropped to 15 percent by 1953, principally for work and shopping. Today, in a much larger metropolitan area that also includes Orange County, 3 to 5 percent of jobs are located downtown (depending on the geographical definition). The area not only lost a significant share of metropolitan employment, but saw its share of retail sales drop as regional shopping centers were built throughout the area. Similar trends occurred in virtually every metropolitan area of the United States.

All of this occured as the automobile facilitated access to virtually everywhere in the metropolitan area, not just downtown.

The emerging polycentricity of the city long was obvious to many analysts, but it was Joel Garreau who brought the issue to popular attention in his classic Edge City: Life on the New Frontier. Garreau documented the development of large suburban employment centers throughout the major metropolitan areas and provided a list. Later, Robert Lang of the University of Nevada Las Vegas took the issue further in his Edgeless Cities: Exploring the Elusive Metropolis, which examined office space outside downtown areas and edge cities in 1999. Gross office space was greatest outside both the downtowns and edge cities, according to Lang’s data (Note 1).

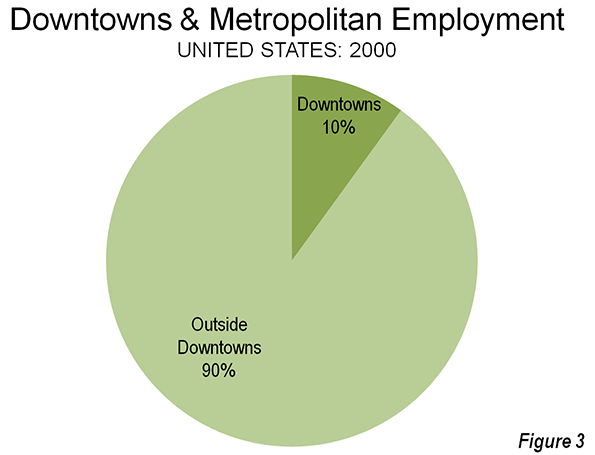

Lang’s analysis is limited to office space, which is more concentrated in downtown areas than employment. On average, 2000 data indicates that downtown areas had approximately 10 percent of employment, well below downtown’s 36 percent share of office space (Figure 3).

Even so, there remains a misconception today that cities remain monocentric. Yet as the figures show we are progressing toward a distribution of jobs that nearly matches its distribution of housing, with the exception of downtown (where there is the greatest imbalance, see below).

Historical Core Municipalities: Where the Jobs-Housing Imbalance is the Greatest

The excess of jobs in relation to residential workers is greatest in the historical core municipalities. It is driven by the downtown areas (central business districts or CBDs), which have by far the highest employment densities in the metropolitan areas. For example, in 2000, the downtown areas of the nation’s 50 largest urban areas had an average job density 92,000 per square mile. This is approximately 70 times the average non-downtown urban area employment densities (1,300 per square mile). Downtown residential densities, if they were readily available, would doubtless be a small fraction of the downtown employment figures.

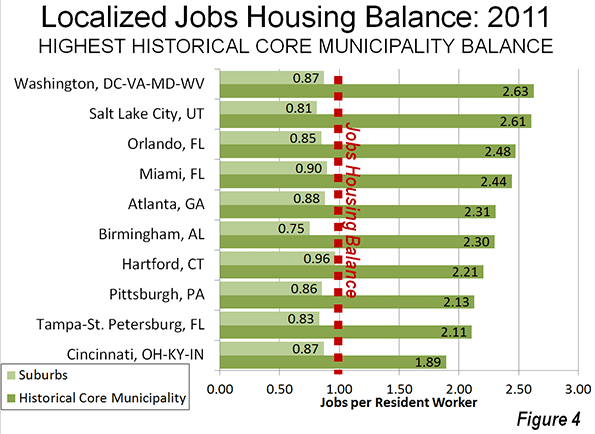

Largest Historical Core Municipality Jobs-Housing Imbalances

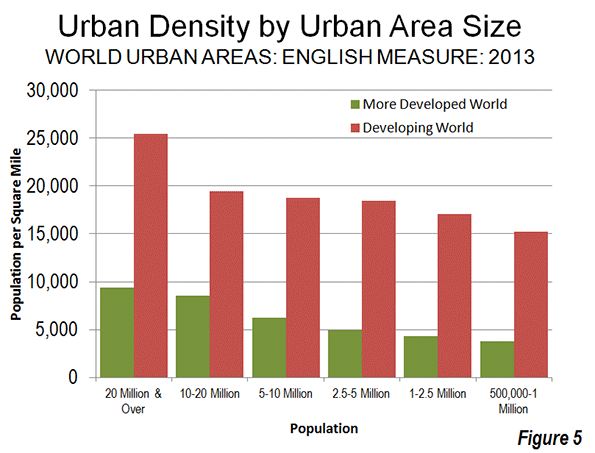

The imbalance between jobs and housing is highest among the historical core municipalities of Washington (2.63), Salt Lake City (2.61), Orlando (2.48), Miami (2.44) and Atlanta (2.31). Yet, these large historical core municipality imbalances co-exist with generally near average suburban jobs housing balances. For example, in Washington there are 0.87 jobs per resident worker in the suburbs, or only 13 percent fewer jobs than workers who reside in the suburbs. In the other four metropolitan areas, the suburban jobs housing balance is above 0.80 (Figure 4).

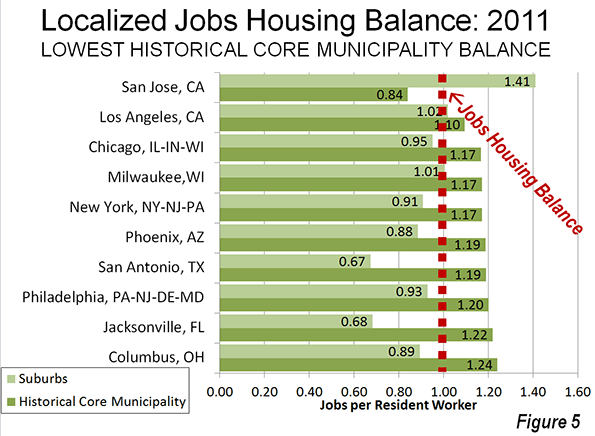

Smallest Historical Core Municipality Jobs-Housing Imbalances

The smallest historical core municipality jobs housing imbalance is in San Jose (0.84), which is the only major metropolitan area in which has fewer jobs than resident workers (Figure 5). However, the municipality of San Jose is a "Post War Suburban" core municipality, having experienced virtually all of its growth since 1940. This is despite the fact that San Jose’s corresponding urban area is the third most dense (following Los Angeles and San Francisco). Generally higher suburban housing densities were built in San Jose compared to less dense urban areas – which extend over vast distances – such as New York, Philadelphia and Boston. San Jose is also the only metropolitan area in which there are more suburban jobs than suburban resident workers (1.41 jobs per worker).

The other historical core municipalities with the least imbalance between employment and resident workers are Los Angeles (1.10), Chicago (1.17), Milwaukee (1.17) and New York (1.17). The surprising inclusion of New York is discussed below.

Each of the historical core municipalities with the fewest jobs per resident worker has a higher than average jobs housing balance in its suburban areas. Los Angeles has 1.02 jobs per suburban resident worker, principally the result of importing workers from the adjacent Riverside-San Bernardino metropolitan area. Milwaukee also has more suburban jobs than suburban resident workers (1.01).

New York

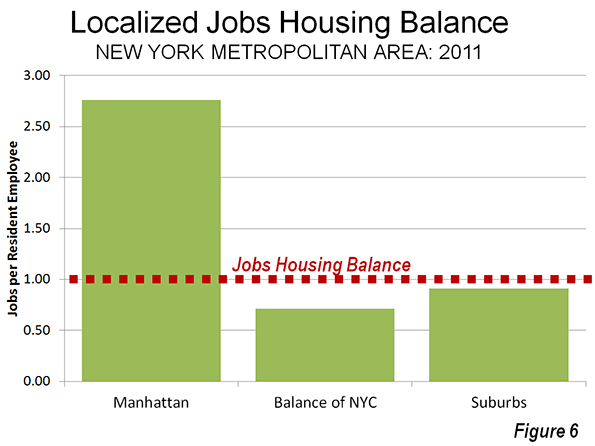

New York has the second largest central business district in the world, following Tokyo. It therefore seems odd that the municipality of New York should have such a low ratio of jobs per resident worker. The borough of Manhattan, where the central business district is located, has 2.76 jobs per resident workers, higher than that of top ranked Washington, DC (above). There are 1,450,000 more jobs than resident workers in Manhattan.

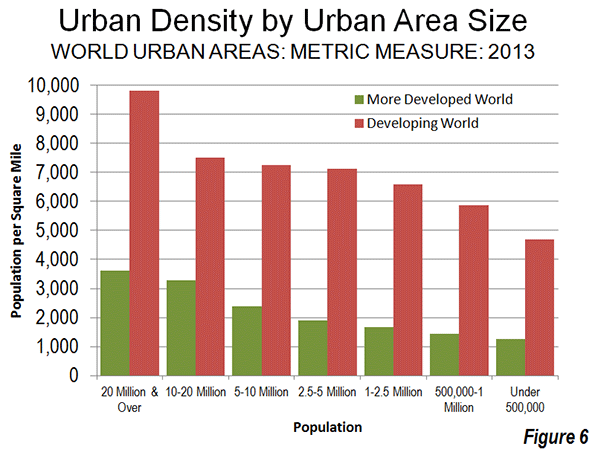

New York’s low ratio is the result of a huge shortage of jobs relative to workers the outer boroughs (the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island). There are 830,000 fewer jobs than resident workers in the four outer boroughs. Their ratio of jobs per resident, at 0.71 is lower than all but five suburban areas in the other 50 major metropolitan areas (Figure 6).

The suburbs of New York, ironically, are more job-rich than the outer boroughs. They boast an 0.91 jobs per resident worker, ranking 17th out of the 51 metropolitan areas.

The New Normal

The former assumption that "everyone works downtown" is a thing of the past. Dispersion of jobs throughout the metropolitan area has become the rule. The "old normal" was that of the bedroom community – people living in the suburbs and working in the core cities. The "new normal" is about downtown and the core city. To the extent that there is a distortion in the jobs housing balance throughout the modern metropolitan area, it is the result of a larger number of jobs than residents in the core cities (and especially downtown).

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

———————-

Photo: Houston downtown (to the left), edge city (Texas Medical Center in the middle) and dispersed employment (rest of photo). Photo by author.

Note 1: The total office space outside the primary downtowns, secondary downtowns and edge cities was 37.0 percent in reviewed 13 metropolitan areas. Primary downtowns accounted for 36.5 percent, secondary downtown for 6.5 percent and edge cities for 19.8 percent (this analysis classifies Beverly Hills, Mid-Wilshire and Santa Monica in Los Angeles as secondary downtowns, rather than as primary as in the book. See tables 4-2 and 4-10).

Note 2: The historical core municipalities are the largest municipalities in each metropolitan area, with the following exceptions.

(a) Oakland and St. Paul are also historical core municipalities.

(b) Norfolk is the historical core municipality in the Virginia Beach metropolitan area.

(c) San Bernardino is the historical core municipality in Riverside San Bernardino

(see Classification of Historical Core Municipalities)