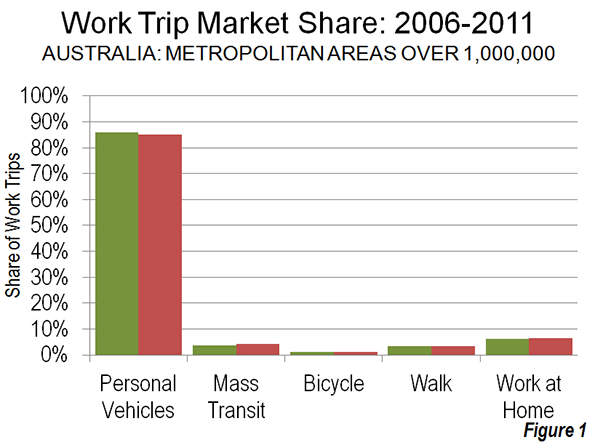

Data from the 2011 censuses indicates that mass transit is gaining market share in all of but one of Australia’s major metropolitan areas. The greatest increase as in Perth, at 21% , aided by the new Mandurah rail line to the southern urban fringe. On average, mass transit’s market share increased by 10.8% in the five metropolitan areas with more than 1 million population. This increase seems likely to be in response to both mass transit service improvements (such as in Perth) and higher petrol (gasoline) prices. The highest mass transit market share is in Sydney, at 22%, approximately equal to that of Toronto and greater than all major US metropolitan areas except New York (31%). Adelaide has the smallest transit market share, at 9.5%, which is nonetheless 50% above that of Portland, to which Adelaide officials have often looked as a model (Figure 1).

At the same time, there was a personal vehicle (automobiles, motorcycles, taxis and trucks) market share in all 5 metropolitan areas, averaging 2.2% (Table). However, the much larger base of personal vehicle use prevented mass transit from materially reducing the share of the automobile in any of the metropolitan areas.

| Work Trip Market Share 2006-2011 | ||||||

| Major Metropolitan Areas in Australia | ||||||

| 2000 | Personal Vehicles | Mass Transit | Bicycle | Walk (Only) | Work at Home | Other |

| Adelaide | 81.2% | 9.6% | 1.5% | 3.1% | 3.5% | 1.2% |

| Brisbane | 76.5% | 13.2% | 1.1% | 3.5% | 4.5% | 1.2% |

| Melbourne | 76.7% | 13.3% | 1.3% | 3.4% | 4.2% | 1.1% |

| Perth | 80.8% | 10.0% | 1.1% | 2.5% | 4.1% | 1.5% |

| Sydney | 69.0% | 20.3% | 0.6% | 4.7% | 4.4% | 1.0% |

| Average | 76.8% | 13.3% | 1.1% | 3.5% | 4.1% | 1.2% |

| 2010 | ||||||

| Adelaide | 81.1% | 9.5% | 1.3% | 2.8% | 3.7% | 1.6% |

| Brisbane | 75.1% | 14.3% | 1.2% | 3.5% | 4.6% | 1.4% |

| Melbourne | 74.5% | 15.4% | 1.5% | 3.3% | 4.1% | 1.2% |

| Perth | 78.1% | 12.1% | 1.2% | 2.6% | 3.9% | 2.0% |

| Sydney | 66.9% | 22.2% | 0.8% | 4.6% | 4.4% | 1.1% |

| Average | 75.2% | 14.7% | 1.2% | 3.4% | 4.1% | 1.4% |

| Change in Market Share | ||||||

| Adelaide | -0.1% | -0.6% | -12.2% | -7.4% | 4.6% | 32.1% |

| Brisbane | -1.8% | 8.3% | 10.5% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 14.4% |

| Melbourne | -2.9% | 15.6% | 17.2% | -4.4% | -1.0% | 10.8% |

| Perth | -3.3% | 21.0% | 11.3% | 4.0% | -3.9% | 30.2% |

| Sydney | -2.9% | 9.4% | 30.3% | -3.6% | -0.4% | 11.1% |

| Average | -2.2% | 10.8% | 11.4% | -2.2% | 0.0% | 19.7% |

| Source: Calculated from Australian Bureau of Statistics data | ||||||

Unlike the United States, where working at home is the fastest growing method of work access (and likely to pass mass transit in this decade), Australia’s working at home share has stayed constant. Working at home is also increasing in Canada.

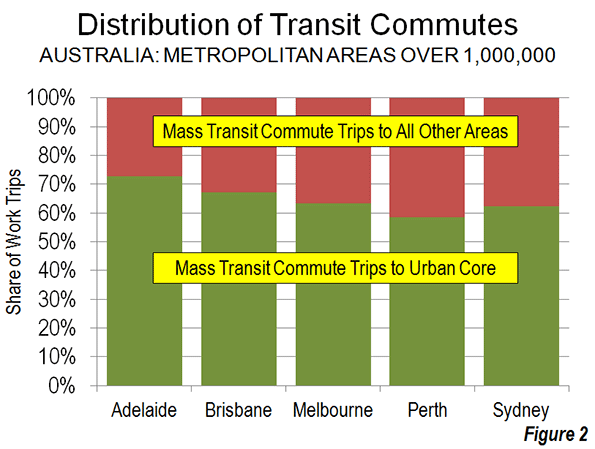

Mass Transit: About Downtown

In Australia, as in Canada and the United States, mass transit is dominated by commuting to the central business district (downtown). On average, 65% of mass transit commuters had a work trip destination in the urban core, which includes the central business district (downtown). This ranges from a low of 59% in Perth to a high of 73% in Adelaide (Figure 2). This concentration of mass transit destinations in the central business district is epitomized by Sydney, where there was a core share of all trips of nearly 60%. By contrast, in Parramatta, which includes one of the largest suburban business centers, is well served by not only the region’s rail system but also by an exclusive busway, the mass transit market share was 15%, one-fourth that of Sydney’s core.

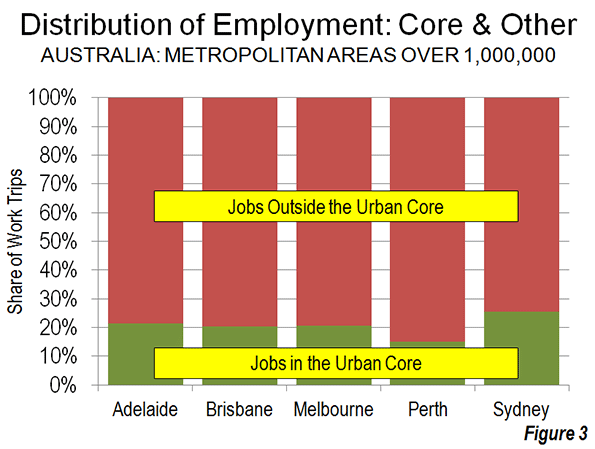

In the five large Australian metropolitan areas, nearly 21% of jobs are located in these urban core areas that include the central business district (Figure 3). The difficulty for transit in serving the nearly 80% of work trip destinations outside the urban core lies with far lower employment densities and mass transit travel times not remotely competitive with the automobile (on the assumption that services even available). On average, mass transit carries 200 times as many commuter to each square kilometer of core land area for each commuter carried per square kilometer in the rest of the urban area (urban centre).

It is not surprising that the central business districts dominate mass transit commuting. They are the only locations in virtually any urban area that have a sufficient employment densities and a comprehensive enough radial rapid transit system to provide no-transfer service to a large number of riders.

Australia’s Long Work Trip Travel Times

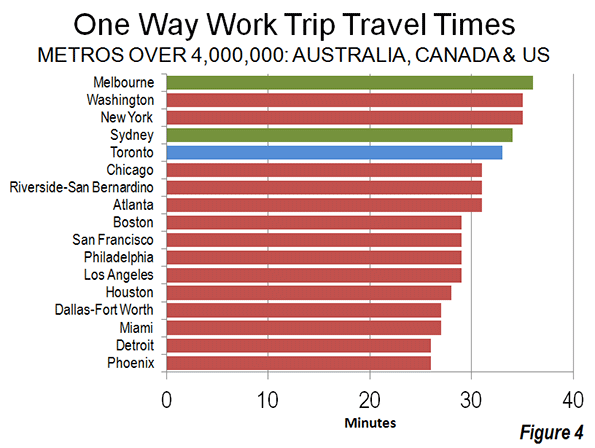

The growth of transit has not reduced travel times but may have boosted it. In fact Australia’s workers already are traveling for longer times to work than in nearly all similar- or larger-sized metropolitan areas in Canada and the United States (Figure 4). For example, the average one-way work trip travel time in Melbourne is 36 minutes, which is longer than that of any major metropolitan area in the US or Canada. Sydney’s one-way work trip travel time is 34 minutes. This exceeds that of all similarly sized or larger metropolitan areas in the three countries with the exceptions of New York and Washington, which are larger. In Improving the Competitiveness of Metropolitan Areas, I cited Statistics Canada data showing that mass transit work trip travel is much longer than by car and that transferring demand to transit would not improve average travel times.

Both Melbourne and Sydney have slightly longer one-way travel times than larger Toronto, which is also larger, at 33 minutes. The Toronto Board of Trade, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, and the Canadian Urban Transit Association have all expressed serious concern about Toronto’s long journey to work time, noting that it places is a competitive disadvantage relative to other metropolitan areas.

Melbourne and Sydney also have longer one-way travel times than all of the other 12 US metropolitan areas with more than 4 million population. Perhaps the starkest comparison is with Los Angeles, often cited as having some of the worst traffic congestion in the high income world. Yet, despite having a urban population density higher than that of either Melbourne or Sydney and a far lower transit work trip market share, Los Angeles has a one-way work trip travel time of 28 minutes The secret in Los Angeles, is more dispersed work locations and a more comprehensive freeway system (though major parts of the planned freeway system were not built).

Far starker is the comparison with Dallas-Fort Worth, which has a population density well below that of both Melbourne and Sydney and a much lower transit work trip market share (2%, compared to 22% in Sydney and 15% in Melbourne). Yet, in Dallas-Fort Worth, the average work trip travel time is 26 minutes, a full quarter less than in Melbourne and 8 minutes less than in Sydney.

Where Should Planners "Put" People?

A recent Infrastructure Australia report (The State of Australia’s Cities: 2012) cites "Marchetti’s Constant," which it characterizes as holding that "people will devote on average 90 minutes a day to travel and no more." (In fact, 90 minutes represents is a full 30 minutes greater than Marchetti indicates: See Note on Marchetti’s Constant).

Infrastructure Australia continues "This suggests that improving the efficiency of urban transport systems by putting people in their economically optimal location within a total travel time of 90 minutes may be the key to improving the productivity of cities."

"Putting people" where they have total travel time of 90 minutes seems a pessimistic goal; Sydney’s average daily travel time is now nearing 80 minutes. This justifies policy makers to further increase its already non-competitive work trip travel times. Economic research associates maximizing the number of jobs that can be reached by people in a metropolitan area in a specified time (such as 30 minutes) is critical to improving city productivity (see The Need to Expand Personal Mobility.)

The issue is not where to "put" people, but rather to facilitate more rapid access for commuters throughout the metropolitan area.

Things are Likely to Get Worse

In the end, there is only so much mass transit can do. Already the Australian metropolitan areas have high transit commute market shares to the cores, which leaves only modest room for improvement. At the same time there is little potential for material increases elsewhere in the metropolitan areas. Automobile competitive transit to these locations would be cost prohibitive, perhaps requiring annual expenditures rivaling the total income of the metropolitan area each year for operations, capital costs and debt service (see Megacities and Affluence: Transport and Land Use Considerations).

Australian urban areas are generally underserved by freeways, despite their overwhelming reliance on personal vehicle travel. At the same time, urban consolidation, “smart growth” land use policies are increasing population densities without accommodating the inevitable associated additional personal vehicle demand (see Urban Travel and Urban Population Density). Things could get worse.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

—–

Methodology: The analysis is based upon Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data for capital city statistical divisions. The urban core was defined as the following local government areas: Sydney, North Sydney, Melbourne, Perth and Adelaide. In Brisbane, where the local government area is far larger, the inner Brisbane census division was used. Consistent data is limited to the central business district is not readily available. All trips which include transit as a mode are counted as transit. Workers who did not work on census day or who did not provide information were excluded from the analysis.

Note on "Marchetti’s Constant:" Not only does Marchetti find a 60 minute, rather than a 90 minute average, but he also credits Zahavi of the World Bank with the concept, noting that with respect to travel: "The empirical conclusion reached by Zahavi is that all over the world, the mean exposure time for man is around one hour per day.” While there are few references to Marchetti’s Constant in the academic literature, it might be more appropriately named "Zahavi’s Constant." In a further irony, Professor Peter Newman, a member of the board of Infrastructure Australia, cited 60 minutes (echoing Marchetti), rather than the 90 minute average in describing the "Zahavi/Marchetti Constant" in a Sydney Morning Herald commentary ("Why We’re in Reaching Our Limits as a One-Hour City" ).

Photo: Downtown Brisbane (by author)