The pejoratively named “trickle-down economics” was the idea that by giving tax breaks to the wealthy and big business, this would spur economic growth that would benefit those further down the ladder. I guess we all know how that worked out.

But while progressives would clearly mock this policy, modern day urbanism often resembles nothing so much as trickle-down economics, though this time mostly advocated by those who would self-identify as being from the left. The idea is that through investments catering to the fickle and mobile educated elite and the high end businesses that employ and entertain them, cities can be rejuvenated in a way that somehow magically benefits everybody and is socially fair.

Trickle down economics type policies failed both because while they contained a great deal of truth – tax rates do matter in economic development – they were a reductionist oversimplification, and perhaps more importantly were self-interested recommendations of the very class that would benefit from them. The tax breaks for the wealthy and big business were in fact the real goals, not primarily policies intended for socially beneficial consequences it was said would result from them.

As it turns out, urbanism in its current form appears to suffer from the exact same problems, as Richard Florida has just documented in an article over at Atlantic Cities called “More Losers Than Winners in America’s New Economic Geography.”

A key question remains: Who benefits and who loses from this talent clustering process? Does it confer broad benefits in the form of higher wages and salaries to workers across the board or do the benefits accrue mainly to smaller group of knowledge, technology, and professional workers?

The University of California, Berkeley’s Enrico Moretti suggests a trickle-down effect, arguing that higher-skill regions benefit all workers by generating higher wages for all workers. Others contend that this new economic geography is at least partially to blame for rising economic inequality.

….

I’ve been examining the winners and losers from this talent clustering process in ongoing research with Charlotta Mellander and our Martin Prosperity Institute team….Our main takeaway: On close inspection, talent clustering provides little in the way of trickle-down benefits. Its benefits flow disproportionately to more highly-skilled knowledge, professional and creative workers whose higher wages and salaries are more than sufficient to cover more expensive housing in these locations. While less-skilled service and blue-collar workers also earn more money in knowledge-based metros, those gains disappear once their higher housing costs are taken into account.

In short, there’s no flow through to people who aren’t directly tapped into the knowledge economy itself. I might add that this probably does include a number of service sector workers like celebrity chefs and personal trainers who cater to the luxury end of services. But the majority of residents are missing out.

To put it in political speak, the creative class doesn’t have much in the way of coattails.

These findings also foot to the implications of Saskia Sassen’s global city theories, in which the global city functions of a region comprise a sort of “city within a city” which has little in common with the rest of the metro region as thus perhaps little impact on it. Indeed, we might even view the two economic geographies as being in conflict.

Florida and Sassen are academics and so can’t necessarily be seen as advocates for the phenomena they describe. They are describing what is, not what should be. The question is, what have policy makers done with this information?

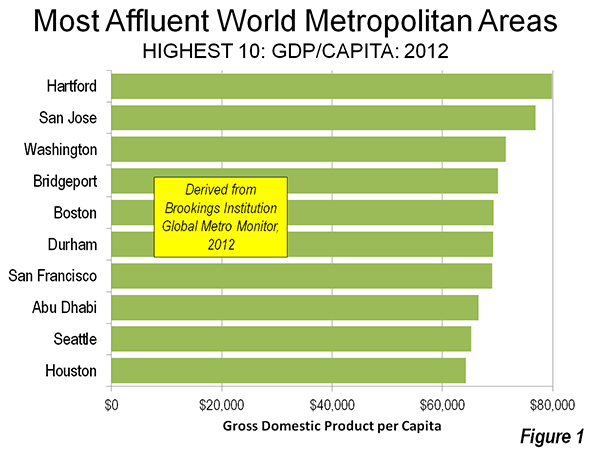

As with the tax rate example, there really is an importance to attracting educated people to your city. College degree attainment explains almost everything about per capita income in a region. (Though as Florida notes, per capita values, as means, can be misleading and median is a better way to do analysis where it’s available).

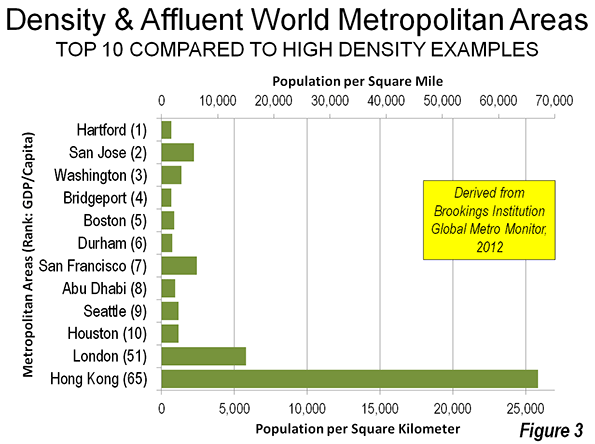

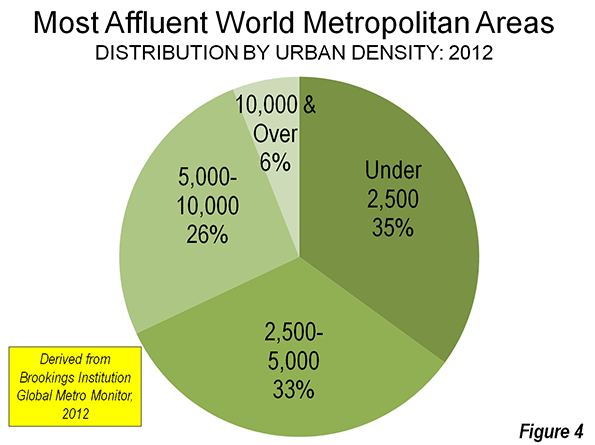

Have urbanists used this as a call to arms to put all of their energy into helping those left behind in the knowledge/creative class economy? No. Instead, urban advocates have gone the other direction, locking onto this in a reductionist way to develop a set of policies I call “Starbucks urbanism.” That is, the focus is on an exclusively high end, sanitized version of city life that caters to the needs of the elite with the claim that this will somehow “revitalize” the city if they are attracted there.

As with trickle-down economics, this a) doesn’t work and b) is being promoted by the self-interested.

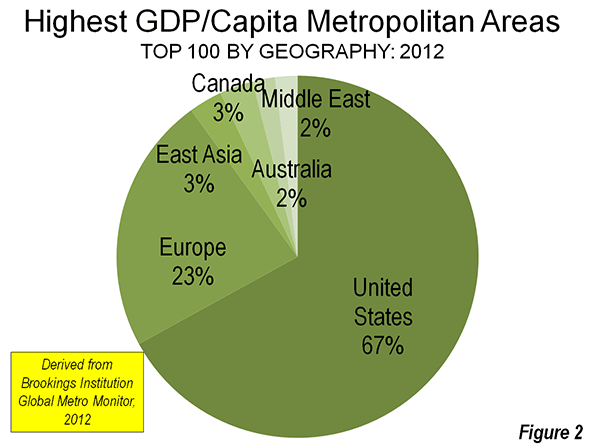

Firstly, it doesn’t work because it more or less operates on the basis of displacement. So it might revitalize certain select districts, but only as physical geographies not human ones. This is exactly because of the phenomenon Florida identified: there are few trickle down benefits to be had. Also, this only works in a handful of districts or in cities that are so small that you can plausibly gentrify the entire thing. The area left behind in these places, as the in the violence stricken neighborhoods of Chicago that are making national news, receive virtually no benefit. And as Bill Frey of Brookings once said, “There aren’t enough yuppies to go around to save Detroit.” Thus only a comparatively small number of cities benefit from talent concentrations anyway. (Indeed, the notion of “concentration” is inherently a relative one).

Secondly, and here I go beyond Florida’s article, urban advocates are a largely self-interested class. Everybody knows that a hedge fund plutocrat is looking out for number one and has a class interest, but if we were honest with ourselves, most of us probably do the same at some different level. For example, it’s easy to cry nepotism when a politician’s relative gets put on the payroll, but if a man gets his son on at the ironworkers union, it generally flies under the radar. I don’t claim to be exempt from this myself.

The people most aggressively pushing urbanist policies like bike lanes, public art, high end mixed use developments, high tech startups, swank boutiques and restaurants, greening the city policies, etc. are disproportionately those who want to live that lifestyle themselves, or hope to someday. Like me in other words. The fact that you’re a Millennial who rides around to microbreweries on your fixie without necessarily having a high paying job yourself (yet) doesn’t matter. You are still advocating for your own preferred milieu, and that of others who think like yourself.

I have observed that when challenged on this, urbanists grow indignant, talking about their commitment to the planet or how transit benefits the poor, etc. But ultimately as with the tax cut advocates, that’s just a self-justification. With some notable exceptions, you don’t see social justice and equity issues front and center in the urbanists discussions outside of old-school community organizing/activism circles, groups that are almost totally distinct from Atlantic Cities style urbanism.

Most urbanists I know are quick to advocate tax increases for the 1% but fail to see how their own policies contribute to a widening of the income gap and class divide in their own cities. Even if they are genuinely motivated to help the entire civic commonwealth, hopefully they recognize that they at least have the same conflict of interest situation they would be quick to highlight in a businessman or politician.

The answer isn’t to junk urbanism. Just as class warfare rhetoric that demonizes the wealthy and business and wants to tax the daylights out of them isn’t the solution to what ails our economy, neither is abandoning many of the principles of urbanism. After all, tax rates do matter for economic growth. Similarly, liveable streets and such are indeed very important to urban revitalization.

What’s needed is a new orientation of these ideas so that we don’t end up with an explicitly elitist policy rationale and policy set that caters to the already privileged at the expense of the poor and middle classes of our cities. We need to be asking the question of what exactly we are doing to benefit the people without college degrees beyond assuring them that if we attract more people with college degrees everything will be looking up for them. We need to sell ideas like transit in a way that isn’t totally dependent on items like “enabling us to attract the talent we need for the 21st century economy.” If I read half as much about providing economic opportunity and facilitating upward social mobility for the poor and middle classes as I do about green this, that, or the other thing, we’d be getting somewhere. (Observe Robert Munson’s recent call to broaden the practical definition of green as one example of starting to think this way). I need to do this as much as anyone.

It’s easy to see why people default to trickle-down type theories even beyond class interest. Both sets of prescriptions – tax cuts for the elite and urbanism for the elite – took place against a backdrop of globalization and deindustrialization that eviscerated the engines of traditional working and middle class prosperity. The answers to how to fix this core problem aren’t obvious. Richard Longworth recently put together a compilation of views on middle class malaise and it is sobering reading.

In a sense, elite boosting policies have “worked” because they’ve successfully boosted the elite – a reasonably tractable problem in the new economy. But they’ve had few benefits to anyone else and have fueled huge class-based resentments that threaten civic cohesion. But just because the problem of opportunity for the poor and middle classes isn’t easy, doesn’t mean it doesn’t need to be solved. Indeed, rebuilding an engine of broad-based prosperity and upward mobility is the signature challenge of our age, and one to which urbanists should be encouraged to apply their fullest efforts.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the founder of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile, where this piece originally appeared.

Chicago skyline photo by Bigstock.