Recent reports of America’s sagging birthrate ‑ the lowest since the 1920s, by some measures ‑ have sparked a much-needed debate about the future of the American family. Unfortunately, this discussion, like so much else in our society, is devolving into yet another political squabble between conservatives and progressives.

Conservatives, including the Weekly Standard’s Jonathan Last, regularly cite declining birth and marriage rates as one result of expanding government ‑ and a threat to the right’s political survival. Progressives, meanwhile, have labeled attempts to commend a committed couple with children as inherently prejudicial and needlessly judgmental.

Yet family size is far more than just another political wedge issue. It is an existential one – essentially determining whether a society wants to replace itself or fall into oblivion, as my colleagues and I recently demonstrated in a report done in conjunction with Singapore’s Civil Service College. No nation has thrived when its birthrate falls below replacement level and stays there – the very level the United States are at now. Examples from history extend from the late Roman Empire to Venice and the Netherlands in the last millennium.

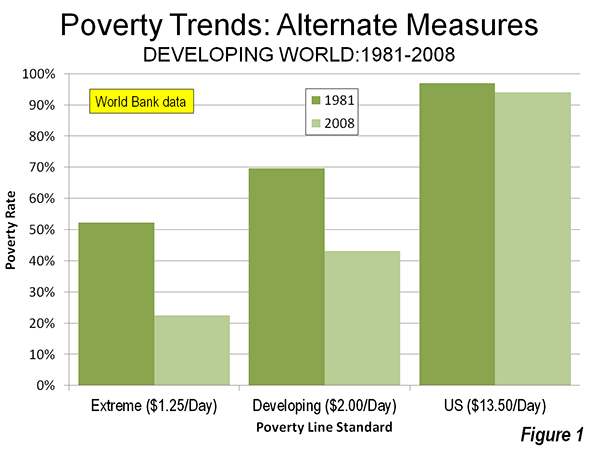

Falling birthrates and declining family formation clearly effect national economies. One major United States’ advantage has long been high birthrates, akin to a developing nation’s, as well as a vibrant family-oriented culture. This was largely because of immigrants and their children, striving first- and second-generation Americans. The United States, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, is expected to have a roughly 40 percent growth in its workforce in the first half of this century, largely thanks to immigration.

In contrast, the Census Bureau predicts that leading U.S. competitors, notably Japan, Europe and South Korea, will likely suffer a decline of 25 percent or more over that time. Even China, whose birthrate has dropped precipitously under its one-child policy and rapid urbanization, is expected to see a sharp drop in its labor force over the next decade.

Perhaps the greatest threat from collapsing fertility is the aging of society. Consider “the dependency ratio,” which measures the number of people in the workforce compared to retirees, in effect, how many working people are needed to support those over age 65. In 1960, before the decline in birthrates, that ratio was 9 percent in the 23 most developed countries. Today, it is 16 percent across these advanced countries. By 2030 it could reach as high as 25 percent.

Countries with the longest history of declines in fertility face the biggest fiscal crises. By 2050, for example, Germany and Singapore are predicted to have roughly 57 people above age 65 for every 100 workers. In the United States, this ratio will rise by 50 percent, to roughly 35 per 100 workers, even if the current decline is eventually reversed.

If birthrates continue to decline, Western nations may devolve into impoverished and enervated nursing homes. And without strong families, children are likely to be more troubled and less productive as adults.

You don’t need a crystal ball to see what this future could look like. Consider Japan. By 2050, there are expected to be three people above age 65 for every person in Japan under 15. In fact, more people are expected to be over 80 than under 15.

This demographic shift signals a kind of death sentence for that once thriving, but now declining, nation. Not only are Japanese couples having far fewer children, sociologist Mike Toyota notes, roughly one-third of Japanese women in their 30s are not getting married ‑ which, in that conservative society, essentially means they are unlikely to have children. Even teenagers, according to a recent government-commissioned study by the Family Planning Association, seem oddly indifferent to dating and sex.

Given the stakes, Americans must forgo political squabbles and focus on practical ways to remove barriers to marriage and child-rearing. One crucial component for strong birthrates is steady economic growth. Before the 2008 economic collapse, the U.S. fertility rate was 2.12, the highest in 40 years. But the tumultuous economic problems since then have helped drive the fertility rate to 1.9 per woman, the lowest since the economic malaise era under President Jimmy Carter in the late 1970s.

Even amid increasing awareness of the country’s demographic problems, however, political extremes focus on their own ideological spin. Conservatives set their arguments in neo-traditionalist terms, embracing right-wing tropes against gay marriage and abortion while blaming expansive government and rampant individualism. Others on the extreme right link declining fertility rates, particularly among Caucasians, to what Pat Buchanan calls “the end of white America.”

Yet conservatives must recognize that fertility is not just a white or high-income Asian issue. Fertility and even marriage rates are, for example, declining throughout much of the Muslim Middle East, in some cases below our own levels, as my colleague Ali Modarres has shown.

Nor is “white America” likely to be demographically overwhelmed by the current dramatic influx of Latino immigrants, particularly Mexicans, as many on the far right insist. Within a generation, Mexican-Americans immigrants’ fertility rates decline to that of native-born U.S. citizens. In fact, as Mexico modernizes, its fertility rates are falling to U.S. levels.

Conservatives also seem to have a hard time admitting that one major culprit ‑ particularly in the United States and East Asian countries such as Singapore ‑ is modern capitalism. Young workers building their careers can face consuming demands for long work hours and substantial amounts of travel. Many confront a choice between a career and family.

“In Singapore,” Austrian demographer Wolfgang Lutz observes, “women work an average of 53 hours a week. Of course they are not going to have children. They don’t have time.”

For hard-pressed low-wage workers, raising children can be even harder. Indeed, much of the decline in child-rearing in the U.S. can be traced to a fall-off among immigrants, particularly Latinos, who fared particularly poorly in the long recession.

On the other side, many Democrats praise the rise of “singlism” ‑ demonstrated by the women in their 40s who never had offspring. This cohort has more than doubled since 1976. Pollsters like Stan Greenberg hail single women as “the largest progressive voting bloc in the country,” and Ruy Texeira, a leading political scientist, asserts that singletons are critical to the “emerging Democratic majority.”

Progressives also embrace urban density ‑ a residential pattern that discourages child-rearing. Unlike the wave of immigrants or rural migrants who flooded the American metropolises of the early 20th century, urbanites today are not raising large families in cramped spaces. Instead, in virtually all high-income societies, high density today almost always translates into low marriage rates and fertility rates.

The causes of this radical change are diverse. But crucial reasons include decline of extended family support networks; erosion of traditional, often religiously based values; and a culture that celebrates individualism.

We no longer see family-centered urban neighborhoods like those depicted in the Chicago of Saul Bellow’s novel The Adventures of Augie March. Instead, many urban centers today are among the most “child free” ‑ whether in Manhattan, San Francisco, inner London or Paris, Singapore, Hong Kong or Tokyo.

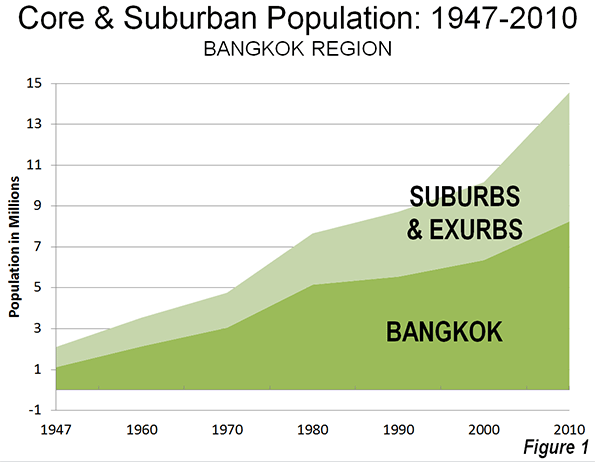

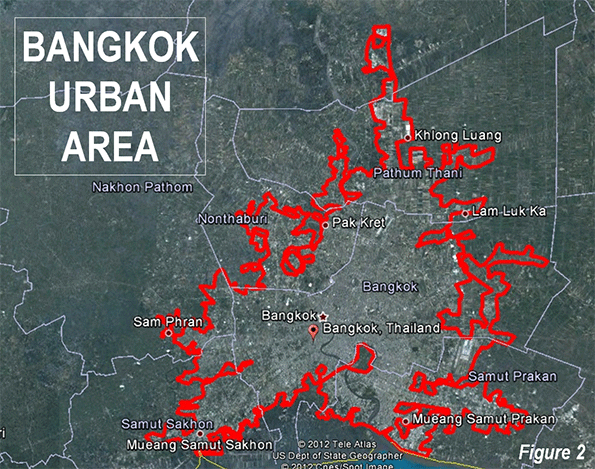

In contrast, America’s nurseries are in the suburbs, exurbs and lower-density greater-metropolitan areas. The metropolitan regions of Atlanta, Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston and Salt Lake City have above-average numbers of children. The percentage of children, according to the census, under age 15 in these cities is almost twice that of Manhattan or San Francisco.

Many progressives don’t seem to care much if the birthrate falls. Some green activists seem to actually prefer it – perhaps viewing offspring, particularly in wealthy countries, as unwanted carbon emitters. They seem to have taken up the century-old Malthusian concerns about overpopulation and environmental ruin. “A whole lot of people don’t have kids BECAUSE they’re worried about the future,” explains one critic of our report, suggesting that concern for the environment may justify the decision not to have children.

Before signing on to a low-fertility agenda, American progressives as well as conservatives might want to consider the long-term consequences. The long fertility-rate declines in Europe and Japan occurred as economic growth flagged. Diminishing expectations of the future, painfully evident in countries such as Spain, Italy and Greece, are now further depressing marriage and childbirth.

As to the culture wars between religious social conservatives and progressives, let’s declare a truce. Spiritual values and traditional families are precious resources to be nurtured. Mormons, evangelicals, practicing Catholics and highly self-identified Jews, all of whom largely favor big families, help make up for the almost certain continued expansion of single, and often childless, people.

Social conservatives also need to champion more than the narrowly defined “natural family.” Many children, whether because of divorce or diverse family circumstances, must look to someone other than their birth parents for nurturing. Adoptive parents, grandmothers, uncles or aunts or other sorts of extended-family units also need to be cherished as committed caregivers.

Popular TV shows like Modern Family show the wide range of family types today. The crucial element is that family obligation often extends well beyond “likes” and ties exist over generations. This can be true for gay couples or “blended families” in a way that can rarely be said of people who are dating, or friends, both of the real and Facebook variety.

Fortunately, the long-term prognosis is not all bad. Pew Research Center reports that the emerging millennial generation rank being good parents, owning a home and having a good marriage as their top three priorities. Generational chroniclers Morley Winograd and Mike Hais, in their book Millennial Momentum: How a New Generation is Remaking America, suggest that the younger generation is as family-oriented as their elders, albeit with a greater emphasis on shared responsibilities and more flexible gender roles.

“No matter how many communes people invent,” the anthropologist Margaret Mead once remarked, “the family always creeps back.” Let’s hope she’s right, not only about the past but the future as well.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and contributing editor to the City Journal in New York. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010.

This piece originally appeared at Reuters.

Baby photo by Bigstock.