The United States Census Bureau has released a report (Patterns of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Population Change: 2000 to 2010.) on metropolitan area growth between 2000 and 2010. The Census Bureau’s the news release highlighted population growth in downtown areas, which it defines as within two miles of the city hall of the largest municipality in each metropolitan area. Predictably, media sources that interpret any improvement in core city fortunes as evidence of people returning to the cities (from which they never came), referred to people "flocking" back to the "city" (See here and here, for example).

Downtown Population Trends: Make no mistake about it, the central cores of the nation’s largest cities are doing better than at any time in recent history. Much of the credit has to go to successful efforts to make crime infested urban cores suitable for habitation, which started with the strong law enforcement policies of former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani.

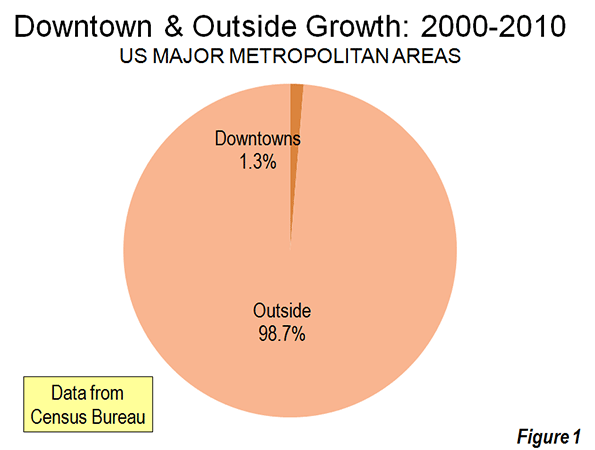

However, to characterize the trend since 2000 as reflective of any "flocking" to the cities is to exaggerate the trend of downtown improvement beyond recognition. Among the 51 major metropolitan areas (those with more than 1 million population), nearly 99 percent of all population growth between 2000 and 2010 was outside the downtown areas (Figure 1).

There was population growth in 33 downtown areas out of the 51 major metropolitan areas. As is typical for core urban measures, nearly 80 percent of this population growth was concentrated in the six most vibrant downtown areas, New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Washington, Boston and San Francisco.

If the next six fastest-growing downtown areas are added to the list (Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, Los Angeles, Portland, San Diego and Seattle), downtown growth exceeds the national total of 205,000 people, because the other 39 downtown areas had a net population loss. Overall, the average downtown area in the major metropolitan areas grew by 4000 people between 2000 and 2010. That may be a lot of people for a college lacrosse game, but not for a city. While in some cases these increases were substantial in percentage terms, the population base was generally small, which was the result of huge population losses in previous decades as well as the conversion of old disused office buildings, warehouses and factories into residential units.

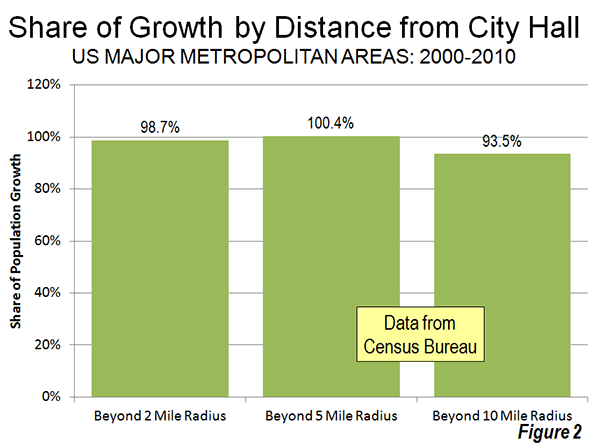

Trends in the Larger Urban Cores: The downtown population gains, however, were not sufficient to stem the continuing decline in urban core populations. Among the 51 major metropolitan areas, the aggregate data indicates a loss of population within six miles of city hall. In essence, the oasis of modest downtown growth was more than negated by losses surrounding the downtown areas. Virtually all the population growth in the major metropolitan areas lay outside the six mile radius core, as areas within the historical urban core, including downtown, lost 0.4 percent.

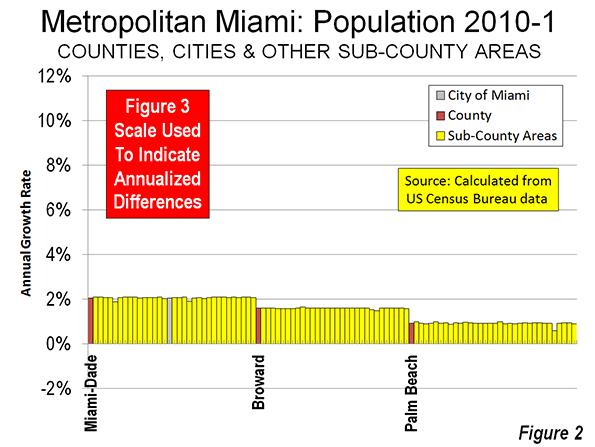

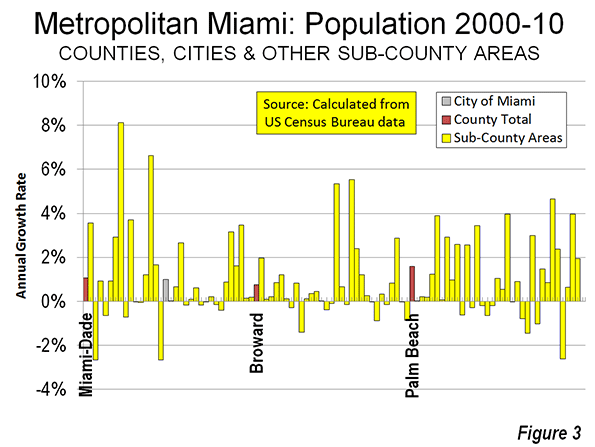

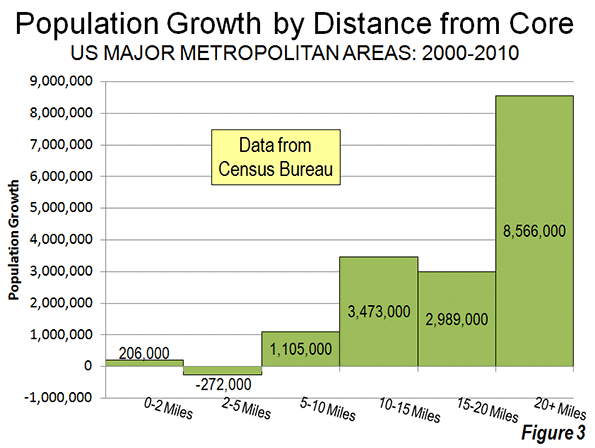

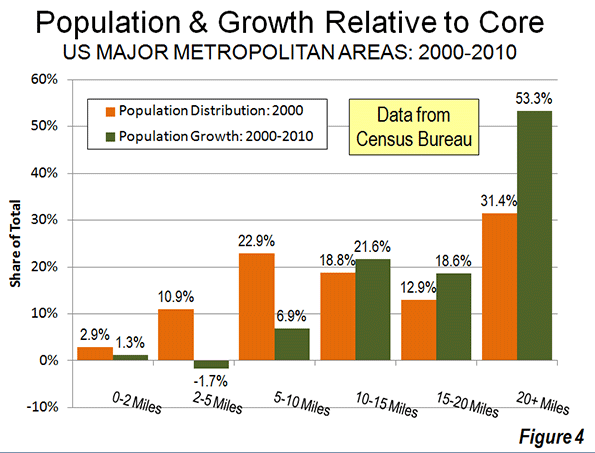

Even when the radius is expanded to 10 miles, the overwhelming majority of growth remains outside. Approximately 94 percent of the aggregate population growth of the major metropolitan areas occurred more than 10 miles from downtown (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows that more than one-half of the growth occurred 20 miles and further from city hall. Further, the population growth beyond 10 miles (10-15 mile radius, 15-20 miles radius and 20 mile and greater radius) from the core exceeded the (2000) share of population, showing the continuing dispersal of American metropolitan areas (Figure 4).

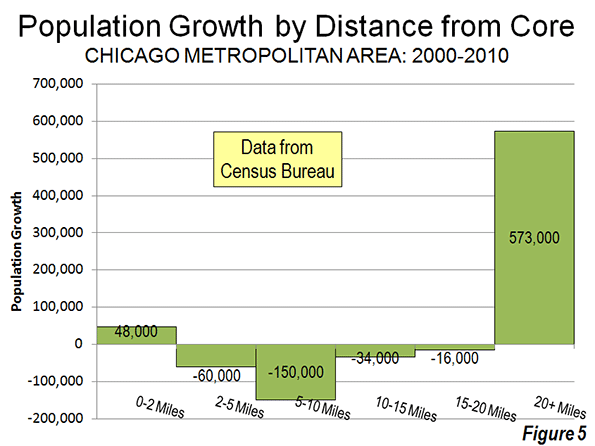

Chicago: The Champion? The Census Bureau press release highlights the fact that downtown Chicago experienced the largest gain in the nation. Downtown Chicago accounted for 13 percent of the metropolitan area’s growth with an impressive 48,000 new residents. However, while downtown Chicago was prospering, people were flocking away from the rest of the city. Within a five mile radius of the Loop, there was a net population loss of 12,000 and a net loss of more than 200,000 within 20 miles (Figure 5). Only within the 36th mile radius from city hall is there a net population gain.

Cleveland: Comeback City and Always Will Be? In view of Cleveland’s demographic decline (down from 915,000 in 1950 to 397,000 in 2010), any progress in downtown Cleveland is welcome. But despite the frequently recurring reports, downtown Cleveland’s population growth was barely 3,000. Despite this gain, the loss within a 6 mile radius was 70,000 and 125,000 within a 12 mile radius. Beyond the 12- mile radius, there was a population increase of nearly 55,000, which insufficient to avoid a metropolitan area population loss.

Other Metropolitan Areas: A total of 30 major metropolitan areas suffered core population losses, despite the fact that many had downtown population increases.

- Five major metropolitan areas suffered overall population losses (Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, Pittsburgh and Katrina ravaged New Orleans).

- St. Louis, with a core city that holds the modern international record for population loss (from 857,000 in 1950 to 319,000 in 2010), experienced a population decline within a 27 mile radius of city hall. Approximately 150 percent of the growth in the St. Louis metropolitan area was outside the 27 mile radius. Even so, there was an increase of nearly 6,000 in the population of downtown St. Louis.

- There were population losses all the way out to a considerable distance from city halls in Memphis (16 mile radius), Cincinnati (15 mile radius) and Birmingham (14 mile radius). The three corresponding downtown areas also lost population.

- Despite having one of the strongest downtown population increases (12,000), population declined within a 10 mile radius of the Dallas city hall. This contrasts with nearby Houston, which also experienced a strong downtown increase (10,000) but no losses at any radius of the urban core.

- Milwaukee experienced a small downtown population increase (2,000), but had a population loss within an11 mile radius.

The other 21 major metropolitan areas experienced population gains throughout. Even so, most of the growth (77 percent) was outside the 10 mile radius. San Jose had the most concentrated growth, with only 24 percent outside a 10 miles radius from city hall. All of the other metropolitan areas had 60 percent or more of their growth outside a 10 mile radius from city hall.

As we have observed before, 2000 to 2010 was, unlike the 1970s and other decades, more friendly to the nation’s core cities, although less so than the previous decade. Due to the repurposing of old offices and other structures, sometimes aided by subsidies, small downtown slivers may have done better than at any time since before World War II. But the data is clear. Suburban growth was stronger in the 2000s than in the 1990s. The one percent flocked to downtown and the 99 percent flocked to outside downtown.

| Population Loss Radius: Major Metropolitan Areas | ||||

| Miles from City Hall of Historical Core Municipality* | ||||

| Major Metropolitan Areas (Over 1,000,000 Population | Share of Metropolitan Growth | Population Loss Radius (Miles) | ||

| "Outside Downtown" (2- Mile Radius) | Outside 5-Mile Radius | Outside 10-Mile Radius | ||

| MAJOR METROPOLITAN AREAS: TOTAL | 98.7% | 100.4% | 93.5% | 6 |

| Atlanta, GA | 99.6% | 101.1% | 99.9% | 9 |

| Austin, TX | 98.1% | 96.7% | 81.9% | 0 |

| Baltimore, MD | 106.5% | 118.7% | 99.5% | 9 |

| Birmingham, AL | 104.2% | 132.5% | 124.9% | 14 |

| Boston, MA-NH | 90.8% | 76.9% | 67.3% | 0 |

| Buffalo, NY | Entire Metropolitan Area Loss | |||

| Charlotte, NC-SC | 99.1% | 97.4% | 75.0% | 3 |

| Chicago, IL-IN-WI | 86.7% | 103.3% | 144.6% | 35 |

| Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN | 105.1% | 126.8% | 135.2% | 15 |

| Cleveland, OH | Entire Metropolitan Area Loss | |||

| Columbus, OH | 100.5% | 104.3% | 86.9% | 7 |

| Dallas-Fort Worth, TX | 99.0% | 101.0% | 100.7% | 10 |

| Denver, CO | 98.0% | 100.3% | 89.8% | 5 |

| Detroit, MI | Entire Metropolitan Area Loss | |||

| Hartford, CT | 99.2% | 92.7% | 67.2% | 0 |

| Houston, TX | 99.2% | 99.5% | 98.0% | 0 |

| Indianapolis. IN | 102.1% | 112.1% | 89.6% | 8 |

| Jacksonville, FL | 100.2% | 106.3% | 85.3% | 8 |

| Kansas City, MO-KS | 99.5% | 109.0% | 113.3% | 12 |

| Las Vegas, NV | 101.4% | 98.0% | 63.6% | 4 |

| Los Angeles, CA | 97.3% | 102.2% | 97.6% | 8 |

| Louisville, KY-IN | 102.5% | 108.5% | 90.9% | 8 |

| Memphis, TN-MS-AR | 101.2% | 118.5% | 143.5% | 16 |

| Miami, FL | 99.4% | 93.0% | 91.3% | 0 |

| Milwaukee,WI | 95.9% | 109.0% | 107.5% | 11 |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN-WI | 97.4% | 99.2% | 100.1% | 7 |

| Nashville, TN | 100.0% | 101.4% | 92.4% | 7 |

| New Orleans. LA | Entire Metropolitan Area Loss | |||

| New York, NY-NJ-PA | 93.5% | 81.7% | 68.9% | 0 |

| Oklahoma City, OK | 100.1% | 96.8% | 83.5% | 2 |

| Orlando, FL | 99.7% | 99.4% | 84.2% | 0 |

| Philadelphia, PA-NJ-DE-MD | 92.6% | 98.8% | 96.3% | 7 |

| Phoenix, AZ | 100.7% | 101.8% | 93.6% | 6 |

| Pittsburgh, PA | Entire Metropolitan Area Loss | |||

| Portland, OR-WA | 95.0% | 91.5% | 62.7% | 0 |

| Providence, RI-MA | 96.2% | 91.7% | 70.1% | 0 |

| Raleigh, NC | 99.6% | 93.0% | 67.7% | 0 |

| Richmond, VA | 95.7% | 91.7% | 70.2% | 0 |

| Riverside-San Bernardino, CA | 99.5% | 97.2% | 85.8% | 0 |

| Rochester, NY | 146.9% | 149.3% | 82.5% | 9 |

| Sacramento, CA | 99.9% | 94.4% | 79.5% | 0 |

| Salt Lake City, UT | 98.9% | 95.1% | 84.1% | 0 |

| San Antonio, TX | 101.1% | 102.5% | 86.7% | 7 |

| San Diego, CA | 96.3% | 94.1% | 90.1% | 0 |

| San Francisco-Oakland, CA | 90.7% | 87.6% | 82.2% | 0 |

| San Jose, CA | 95.1% | 79.1% | 24.3% | 0 |

| Seattle, WA | 96.5% | 91.9% | 81.4% | 0 |

| St. Louis,, MO-IL | 94.8% | 119.7% | 148.9% | 27 |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg, FL | 98.6% | 97.8% | 83.7% | 0 |

| Virginia Beach-Norfolk, VA-NC | 93.1% | 90.1% | 82.3% | 0 |

| Washington, DC-VA-MD-WV | 97.5% | 94.5% | 87.9% | 0 |

| Calculated from Census Bureau data | ||||

| *Except in Virginia Beach-Norfolk, Where Virginia Beach is used | ||||

——-

Notes:

Population Weighted Density: In its report, the Census Bureau uses "population-weighted density," rather than average population density to compare metropolitan areas. The Census Bureau justified this use as follows:

"Overall densities of CBSAs can be heavily affected by the size of the geographic units for which they are calculated. Metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas are delimited using counties as their basic building blocks, and counties vary greatly across the country in terms of their geographic size. With this in mind, one way of measuring actual residential density is to examine the ratio of population to land area at the scale of the census tract, which—of all the geographic units for which decennial census data are tabulated—is typically the closest in scale to urban and suburban neighborhoods".

The Census Bureau rightly points out the problem with comparing metropolitan area density. However, it is a problem of the federal government’s making, by virtue of using metropolitan area building blocks (counties) that are sometimes too large for designation of genuine metropolitan areas. These difficulties have been overcome by the national census authorities in Japan in Canada, for example, where smaller building blocks are used (such as municipalities or local government authorities).

Further, the Census Bureau already has a means for measuring population density at the census tract level, which is "the closest in scale to urban and suburban neighborhoods." This is the urban area.

"Population-weighted density" is an interesting concept that can provide an impression of the density that is perceived by the average resident of the metropolitan area. Unfortunately, in its report, the Census Bureau is less than precise with its terminology and repeatedly fails to modify the term density with the important "population-weighted" qualification. This could lead to considerable misunderstanding.

The Census Bureau did not provide average population densities based for the mileage radii. Because of large bodies of water (such as Lake Michigan in Chicago can reduce land areas, it was not possible to estimate population densities by radius.

Census Bureau Revision of Incorrect Report: We notified the Census Bureau of errors in its press release and report on September 27. The problems included substitution of San Francisco population data for Salt Lake City as well as metropolitan population in the supporting spreadsheet file. On September 28, the Census Bureau issued a revised press release and report to rectify the errors. Later the erroneous spreadsheet was withdrawn and had not been re-posted as of October 1. We have made corrections to the spreadsheet for this analysis.

Note: Larger "Downtown" Populations in Smaller Metropolitan Areas: Because of the broad 2-mile radius measure used by the Census Bureau, most of the population increase characterized as relating to downtown occurred outside the major metropolitan areas. This is simply because in smaller metropolitan areas, such an area (12.6 square miles) will necessarily contain a larger share of the metropolitan area. Further, many smaller metropolitan areas are virtually all suburban and had experienced little or no core population losses over the decades that have been so devastating to many large core municipalities. On average, 2.7 percent of the population of major metropolitan areas was within a two-mile radius of city hall in 2010. By comparison, in smaller metropolitan areas, approximately 12.7 percent of the population was within a two mile radius.

Photograph: Chicago Suburbs: (where nearly all the growth occurred), by author