Zürich is the largest urban area in Switzerland. The core city (stadt) of Zürich is located at the northern end of Lake Zürich, which is glacial and similar to the "finger lakes" of upstate New York. Lake Zürich is approximately 25 miles/40 kilometers long and 1-2 miles/1.5-3 kilometers wide. The urban area extends south along most of the lake and over hills to the East and West and further North.

Zürich, like larger Paris and Barcelona is a favorite among urban aficionados. Two reasons: the apparent compactness of its urban core and it has one of the world’s best transit systems. Yet, as is shown below, Zürich looks and feels denser than the reality experienced by its citizenry. Moreover the urban core is surrounded by a sea of anything-but-compact suburbanization, as is the case in Paris and virtually all other large Western urban areas. A visit confined to the smallish, but architecturally pleasing precincts of the core can lead to a profound misinterpretation of the urban form (See Louvre Café Syndrome: Misunderstanding Amsterdam and America).

The City of Zürich (Stadt)

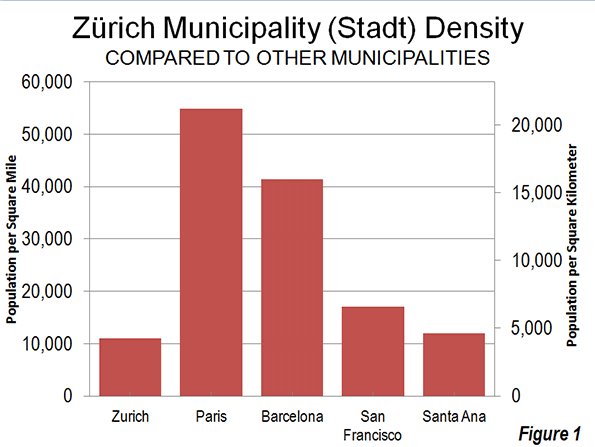

Like virtually all European core cities that have not substantially annexed new land or consolidated with other jurisdictions, the city of Zürich has lost population. Zürich reached its population peak in 1960, with 440,000 people. Since that time, the population has fallen to 373,000, a loss of 15 percent. The city is not very dense despite its reputation to the contrary. The land area is 34 square miles/89 square kilometers, which yields a 2010 population density of 11,000 per square mile/4200 per square kilometer. This is less than two thirds the density of the city of San Francisco and similar to that of some Los Angeles suburbs, such as Santa Ana, Inglewood or Alhambra (Figure 1).

The city is divided into nine districts. The densest, the 5th district, covers 1.1 square miles/2.9 square kilometers and has a density of 24,000 per square mile/9200 per square kilometer. By comparison, Westlake, the most densely populated community planning district in the city of Los Angeles covered three times as much land and had a population density of 34,000 per square mile/13,000 per square kilometer in 2000 (latest data available). This is 40 percent greater than the highest Zürich district density.

The Urban Area

According to the Federal Office of Statistics (FSO), the Zürich urban area (urban agglomeration) has a population of approximately 1.2 million and covers a land area of 420 square miles/1085 square kilometers. The population density is comparatively low, at 2800 per square mile/1075 per square kilometer.

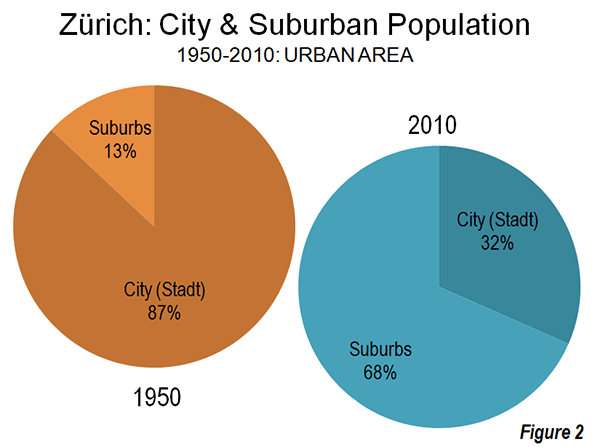

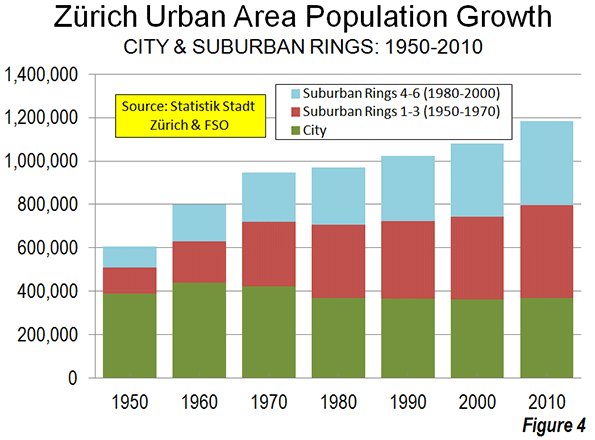

Zürich’s development since World War II has mirrored the international trend towards suburbanization. In 1950, the urban area included the city of Zürich and 14 additional municipalities. The city, with a population of 390,000, contained more than 85 percent of the urban area population as defined at that time. Since 1950 all growth in the Zürich urban area has been in the suburbs. By 2010, the city of Zürich represented only 32 percent of the urban area population (Figure 2). Suburban areas account for 68 percent of the population and more than 90 percent of the urban land area.

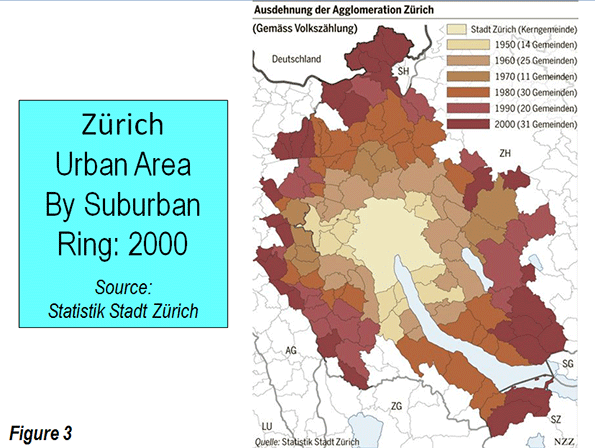

At each decennial census year, FSO adds new municipalities to the urban area as appropriate. In 1950, the urban area included the city of Zürich as well as 14 additional municipalities. By 2000, the urban area included the city of Zürich and 130 other municipalities (Figure 3). FSO is reviewing 2010 census results and is likely to add more municipalities to the urban area within the next year. The population of the urban area as presently defined has nearly doubled since 1950. The population trend for the city of Zürich and the six suburban rings (as presently defined) is illustrated in the Table.

| Zürich Urban Area: Population of Core Municipality & Suburban Rings: 1950-2010 | |||||||

| 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | |

| Urban Area: (Agglomeration Zürich) | 605,765 | 801,124 | 947,011 | 970,073 | 1,021,859 | 1,080,728 | 1,188,566 |

| City of Zürich (Stadt) | 390,020 | 440,170 | 422,640 | 369,522 | 365,043 | 363,273 | 372,857 |

| 1st Ring (1950) | 59,324 | 97,124 | 132,014 | 136,787 | 135,777 | 138,936 | 153,674 |

| 2nd Ring (1960) | 45,989 | 73,560 | 120,492 | 140,088 | 154,226 | 168,812 | 192,469 |

| 3rd Ring (1970) | 13,396 | 19,135 | 44,178 | 59,823 | 67,567 | 73,364 | 82,693 |

| 4th Ring (1980) | 64,259 | 83,036 | 113,195 | 132,444 | 145,165 | 159,021 | 183,878 |

| 5th Ring (1990) | 32,777 | 41,483 | 52,329 | 60,240 | 72,402 | 82,862 | 94,244 |

| 6th Ring (2000) | 46,616 | 62,163 | 71,169 | 81,679 | 94,460 | 108,751 | |

| 1950 Population for 6th Suburban Ring (2000) Not Available | |||||||

| Source: Statistik Stadt Zürich & FSO | |||||||

In recent decades, population growth has gradually moved farther to the periphery of the urban area. This is illustrated by Figure 4, which shows a population trends for the city, the first three suburban rings (1950 to 1970) and the outer three suburban rings (1980 to 2000). By 2000, the three inner suburban rings exceeded the population of the city of Zürich. The outer three suburban rings passed Zürich in population by 2010 (Photo: Suburbs of Zürich).

Suburbs of Zürich

Suburbs of Zürich

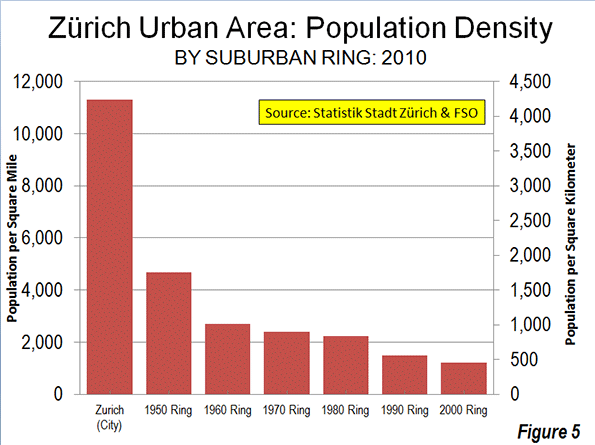

Suburban densities are considerably lower than that of the city of Zürich. Suburban Zürich has an overall population density of approximately 2100 per square mile/800 per square kilometer. As would be expected, the population densities decline substantially with distance from the city of Zürich (Figure 5). The first ring suburbs (1950) have a population density of 4500 square mile/1800 per square kilometer. This is about a quarter higher than the aggregate suburban density of Portland or New York, but only two-thirds as dense as the Los Angeles suburbs. The lowest population density is in the sixth suburban ring (2000) at approximately 1200 per square mile/450 per square kilometer. This is slightly above the approximate 1000 per square mile/400 per square kilometer international standard used by national statistics agencies in designating urban areas (Note 1).

Similarly, employment has become more dispersed as jobs follow residents toward lower density suburban areas. Less than 15 percent of the urban area’s employment is in the central business district, a figure similar to that the average of US, Canadian and Australian urban areas.

Getting Around and To Zürich

Zürich is served by one of the world’s most effective transit systems, which necessarily focuses on the central business district and provides an intense mesh of service in the core city. Among the approximately 90 urban areas of the world for which the Millennium Cities Database provides service information, Zürich ranked 22nd in transit service intensity (transit vehicle kilometers divided by urban area square kilometers), with a service-level approximately 15 percent that of Hong Kong (Note 3). Among the European urban areas surveyed, only Barcelona and Milan had more intense transit service.

However, as is the case in all urban areas of Western Europe (as well as the United States, Canada and Australia), the overwhelming majority of motorized travel in the Zürich urban area is by car. Zürich’s automobile market share, in distance traveled, is approximately 75 percent, similar to that of Paris and approximately 15 percent below that of the New York, Toronto or Sydney urban areas.

Zürich, as the nation’s largest urban area, is unique in not having been linked to its national freeway (motorway) system until recently. Only since 2009 has Zürich been connected to nearby Lucerne (only 30 miles/50 kilometers away) or beyond through the St. Gotthard tunnel to Milan and the South. The new Uetliberg Tunnel (A4 motorway) connects to the exurb of Zug. For the first time Switzerland’s main north-south motorway connects to its principal route, the east-west A1 motorway (Note 2).

No motorway dissects the city of Zürich. However, a swath is cut through the city of Zürich by the national railway system. Starting at Zürich Station and extending to the north city limits, the railway divide is from 150 to 450 meters/650 to 1500 feet wide (Photo: Zürich Railway Divide). This may be wider than any freeway in the world. For example, the 26-lane Katy Freeway in Houston, the 18-lane Autopista Panamericana in Buenos Aires and the 14-lane MacDonald Cartier Freeway in Toronto all have average widths of 150 meters/650 feet or less.

Zürich Railway Divide (from Hardbrücke)

Zürich Railway Divide (from Hardbrücke)

Zürich: Compact Core, Suburban Reality

Like urban residents throughout the high-income world, the residents of Zürich (and other Swiss urban areas) have chosen to live in larger, more comfortable houses, often with yards (gardens). At the same time, the historical urban core remains intact as a frequent or occasional destination for both tourists and residents, most of whom live in the suburbs.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

—–

Photo: Zürich Urban Core Street Scene (photos by author)

Note 1: Such as INSEE (France), National Statistics (UK), Statistics Canada, United States Census Bureau, Census of India,

Note 3: According to Millennium Cities Database information, only Manila had more intense transit service than Hong Kong (85 percent higher service intensity).

Note 2: Switzerland speed limits are slow by European standards, but generally higher than those in the United States, Canada and Australia. The national speed limit on the motorway system is 120 kilometers per hour/75 miles per hour. Speed limits are higher in France and Italy at 130 kilometers per hour/81 miles per hour. In Germany, most of the autobahn system is not subject to speed limits. The highest speed limit in the United States is now planned for a new toll road (C-130) between San Antonio and Austin, at 85 miles per hour/137 kilometers per hour and on some other Texas and Utah roads at 80 miles per hour/129 kilometers per hour. Elsewhere in the United States, Canada and Australia, speed limits are lower than in Switzerland and nearly all Europe.

Favela and Affluence, core city of São Paulo

Favela and Affluence, core city of São Paulo