The online reaction to the reports on racial segregation in New York state’s public schools reminded me, yet again, that most people think of New York as an integrated city, and are surprised or incredulous when that impression is contradicted.

This is somewhat jarring, since virtually every attempt to actually measure racial segregation suggests that New York is one of the most segregated cities in the country. This University of Michigan analysis of 2010 Census data, for example, suggests that New York is the second-most-segregated metropolitan area in the U.S., exceeded only by Milwaukee, and that about 78% of white and black people would have to move in order to achieve perfect integration. (Chicago’s corresponding number is just over 76%, good enough for third place.)

Why is this so surprising? One obvious reason, I think, is that most people’s conception of New York is limited to about 1/2 of Manhattan and maybe 1/6 of Brooklyn, areas that are among the largest job and tourist centers in the world. As a result, they attract people of all different ethnic backgrounds, especially during the day, even if the people who actually live in those areas tend to be monochromatic. Imagine, in other words, trying to judge racial segregation in Chicago by walking around the Loop and adjacent areas: you would probably conclude that you were in a pretty integrated city.

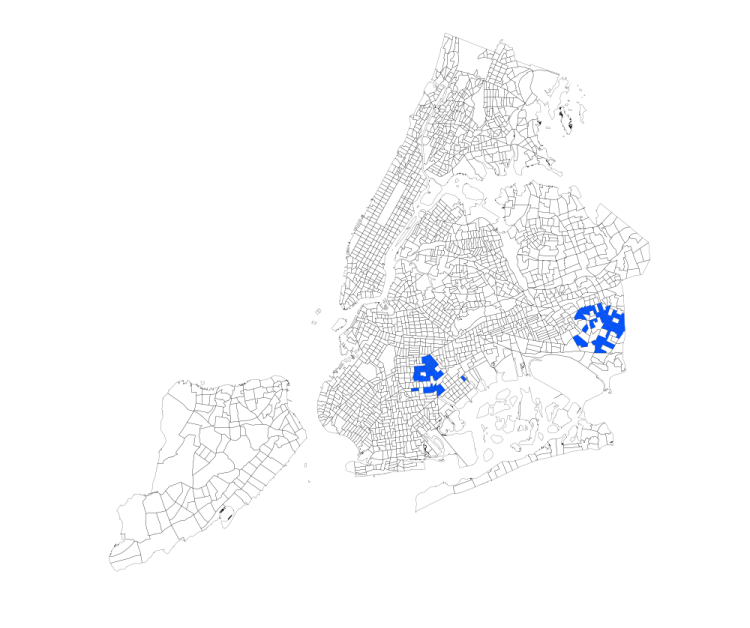

But it goes beyond that, I think. Segregation in New York doesn’t look like segregation in Chicago, or a lot of smaller Rust Belt cities. For one, there just aren’t very many monolithically black neighborhoods left in New York. Here, for example, I’ve highlighted every neighborhood that’s at least 90% African American (see note on method at the bottom of this piece):

Were we to do this in Chicago, half the South and West Sides would be lit up. But in New York, black neighborhoods have become significantly mixed, in particular with people of Hispanic descent. This is a phenomenon Chicagoans are used to in formerly all-white communities – places like Jefferson Park or Bridgeport, which as recently as 1980 were overwhelmingly white, now have very large Latino and Asian populations – but in New York, it’s happened in both white and black neighborhoods.

That said, white folks in New York have still on the whole declined to move to black areas, except for some nibbling along the edges in Harlem and central Brooklyn. That means that instead of measuring segregation the way we might in Chicago – by looking for very high concentrations of a single ethnic group – it makes more sense to look for the absence of either white or black people.

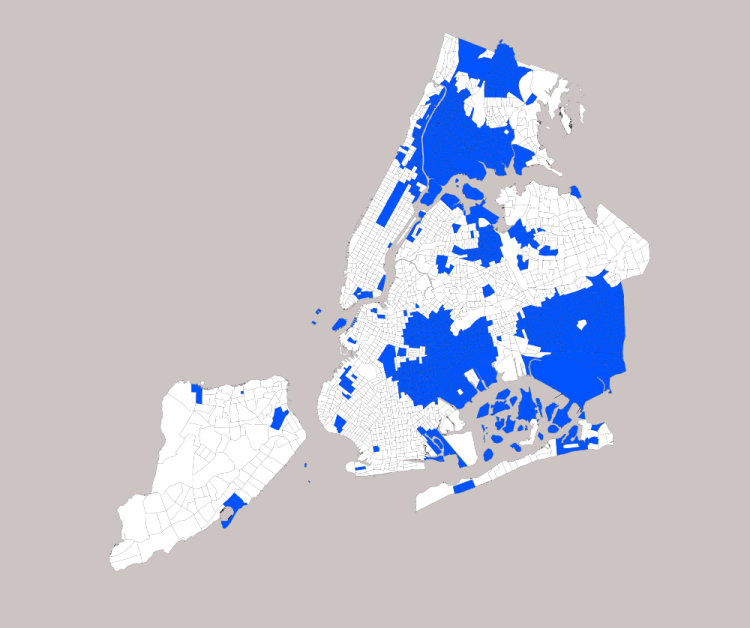

Here, then, I’ve highlighted all the places where white people make up less than 10% of the population:

It’s a lot. And, correspondingly, here are all the places where black people make up less than 10% of the population:

It’s also a lot. And if we put the two maps together, we see that these two categories cover the overwhelming majority of NYC:

The same pattern holds pretty well if we lower the threshold to no more than 5% white or black:

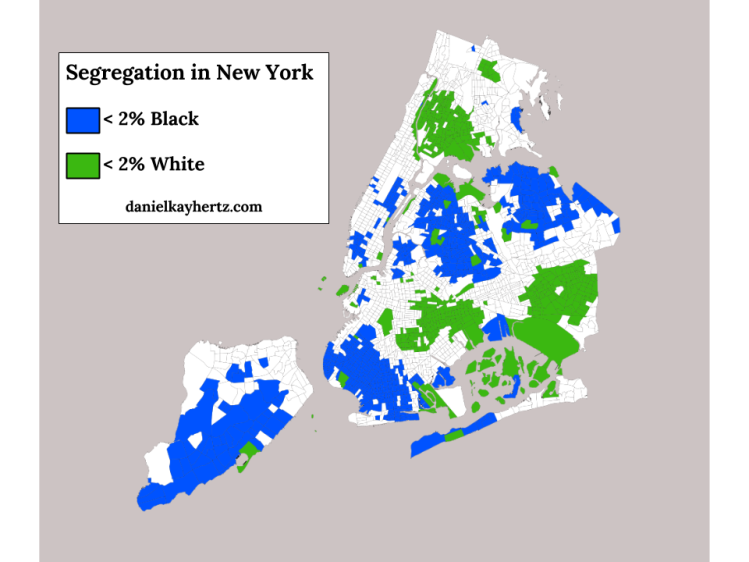

And there are even a significant number of areas that are truly hypersegregated, with fewer than 2% of residents being either white or black:

Because I now love GIFs, here’s a summary GIF.

What does all this tell us? For one, it confirms graphically what the Census numbers suggested, which is that the median black New Yorker lives in a neighborhood with very few white people, and vice versa.

But it also suggests a racial landscape that looks different from that of Chicago, and lots of other American cities, in important ways. In particular, where Chicago has a relatively simple racial geography – white neighborhoods at various levels of integration with Hispanics and Asians to the north and northwest, black and Hispanic neighborhoods to the south and west, with only a few small islands like Hyde Park and Bridgeport that break the pattern – New York’s segregated neighborhoods form a more complex patchwork across the city. That means that while a North Sider in Chicago might go years without having to even pass through a black neighborhood, lots of white New Yorkers have to get through the non-white parts of Brooklyn or the Bronx to reach job and entertainment districts in Manhattan or northern Brooklyn.

I imagine that structural-geographic fact, combined with New York’s relatively high level of black-Hispanic integration, goes a long way to explaining my anecdotal experience that white New Yorkers tend to be less ignorant and scared of their city’s non-white neighborhoods than white Chicagoans are of Chicago’s. (There’s some interesting research that suggests white people tend to be more sympathetic to brown people, and their neighborhoods, than black people and theirs.) There’s also, of course, the fact that Chicago’s segregated non-white neighborhoods tend to have much higher violent crime rates, and much more modest business districts, than New York’s, although that’s likely both an effect and cause of their relative isolation.

All of this is another reason that I’m kind of excited about the growing entertainment and shopping district on 53rd St. in Hyde Park, since the more that the South Side has “neighborhood downtown” strips that draw people from across the city, the more likely North Siders and suburbanites are to travel through the black and Latino neighborhoods that surround them, observe that many of them are actually quite nice, become less committed to shunning them, and thus contribute less to the social and economic dynamics that have created the institution of the ghetto, and the poor job prospects, failing schools, and high crime rates that accompany it.

In conclusion: New York is super segregated, but the numbers aren’t everything.

Also, let me have another Talk To Me Like I’m Stupid moment: suggestions for books about the racial history of New York? What’s the equivalent of Making the Second Ghetto or Family Properties? I’ve already read Caro’s Moses book.

Note: This piece focuses on white-black segregation because that, for various social and historical reasons, has been by far the most significant geographic separation in American cities, certainly in the Midwest and Northeast. But by far the second most significant separation – white-Latino segregation – is also very extreme in New York. The same Census analysis that found NYC was the second-most-segregated metro area in terms of white and black people found that it was the third-most-segregated metro area in terms of white and Latino people. That’s obviously not the end of the story either, though. If you know about or are curious about some other aspect of segregation, leave a comment.

Daniel Hertz is a masters student at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago. This post originally appeared in City Notes on April 14, 2014.

Photo by Mike Lee