The recent near breakup of the United Kingdom — something inconceivable just a decade ago — reflects a deep, pervasive problem of identity throughout the EU. The once vaunted European sense of common destiny is decomposing. Other separatist movements are on the march, most notably in Catalonia, Flanders and northern Italy.

Throughout the continent, public support for a united Europe fell sharply last year. Opposition to greater integration has emerged, with anti-EU parties gaining support in countries as diverse as the United Kingdom, Greece, Germany and France.

The new reality is epitomized by France’s ascendant far-right political figure, Marine Le Pen, who is now leading in many polls to win the next presidential election. “The people have spoken loud and clear … they no longer want to be led by those outside our borders, by EU commissioners and technocrats who are unelected,” she declared recently. “They want to be protected from globalization and take back the reins of their destiny.”

These attitudes suggest that the EU could be devolving from a nascent super-state to something that increasingly resembles the Holy Roman Empire, a fragmented landscape of small, unimportant states wrapped in a unitary, but ephemeral crepe. This challenges the view of some Americans, particularly but not only on the left, who see Europe as a role model for the U.S.

Not long ago progressive authors like Jeremy Rifkin could project the European Union to be one of the world’s great and admirable powers. Today, Rifkin’s 2005 tome “The European Dream,” and a host of similar tracts, seem absurd amid growing political unrest and spreading economic stagnation.

Economic Decline

Some pundits, such as Paul Krugman, routinely describe Europe’s approach to economic, environment and social policy as more enlightened than America’s. Wherever possible, progressives push for European-style action in areas such as curbing carbon emissionsand rapidly converting to “green” energy.

Yet these policies are not working. The one large relatively fast-growing economy in Europe (excluding Turkey) is Poland.

Several years ago Germany and the Netherlands were exemplars as opposed to the much-disdained PIGS (Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain). But German growth rates have plummeted, going negative in the last quarter, along with France and Italy. More stagnation is likely as energy costs surge and key export markets, notably in Russia and China, begin to contract. Today, the “sick man” of Europe is not any one country, or collection of countries; the “sick man of Europe” is Europe.

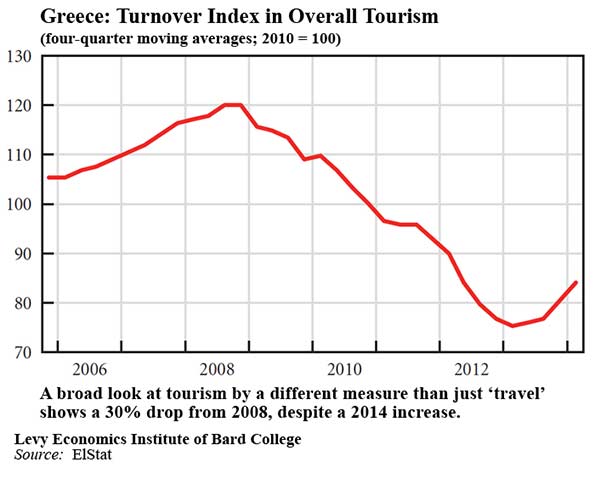

Europe’s poor economy stems in large part from policy. The strong welfare state so admired by progressives here has also made Europe a very expensive place to do business. High taxes and welfare costs, long tolerable in an efficient economy like Germany, have a way of catching up with companies and countries. This has been particularly notable after the financial crisis; since 2008 the unemployment rate has shot up 5 percentage points while dropping steadily in the Untied States.

The European-wide embrace of “green” energy policies has been tough particularly for manufacturers. Under Chancellor Merkel, Germany has embraced a massive shift to green energy that has helped raise electricity costs for companies by 60% over the past five years to double the rates in the United States.

The Russians, Europe’s one relatively inexpensive energy source, may have calculated that, in the long run, China may prove a better customer than the Europeans. Ironically, some European countries, including Germany, have been forced to boost their use of coal, certainly not much of a climate change win, to make up for shortfalls created by shuttering nuclear plants and overreliance on often erratic green energy.

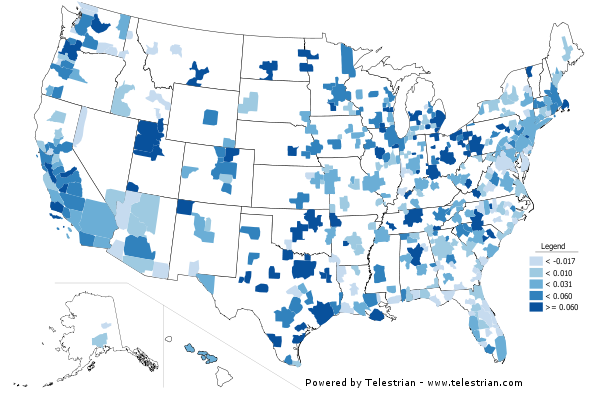

Ultimately, high energy prices tend to fall most painfully on the middle and working classes in the form of higher electricity bills. Some may see their jobs threatened as European employers look forlower-cost alternatives, such as in the energy rich South and middle of the United States.

Demographic Disasters

The young are arguably the biggest losers in Europe’s decline. Even though birthrates are very low throughout much of Europe from Germany, Italy and Spain to the eastern countries, those now coming into the workforce face extraordinarily high levels of unemployment, topping 50% in some places. It’s no wonder that some are dubbing them a “lost generation.”

The combination of low birth rates and declining prospects contribute to rising concerns about immigration. Immigration has always been a more contentious issue in Europe, where many countries are dominated by a single ethnic group and the residents prefer something closer to homogeneity. This nativism has been painfully evidenced in recent decades from everything from the violent breakup of Yugoslavia and the far more civilized dismantling of Czechoslovakia to assaults on the Roma in France, the Czech Republic, Greece and other countries.

In Britain, the anti-immigrant and anti-EU U.K. Independence Party’s recent strong showing in the European Parliament elections reflected this concern. Diversity in London, which by some counts has the world’s largest concentration of immigrants, thrills London’s media and business communities but stirs great resentment, particularly among working and middle-class voters. The fact that by some estimates that most new jobs generated in the recovery have gone to immigrants has not warmed sentiments.

A Region Without Meaning

Chancellor Merkel has noted that “multi-culturalism” in Germany has “utterly failed.” Muslims in Europe drifting to ISIS is just one reflection of the continent’s weakness. The slow integration of immigrants into the economy, even in relatively prosperous, enlightened countries like Sweden, reflects also the inability of Europeans to integrate the newcomers who could help provide a workforce and consumer base in the future.

Perhaps the greatest challenge to Europe is not demographics, economics or energy, but one of identity. In highly secularized Europe, Christianity, which bound the continent around some similar values, is increasingly rarely practiced or believed. More Czechs, for example, believe in UFOs than in God. Outside of some vaguely anti-American, neo-druid communitarianism among some, there’s not much holding Europeans together.

All this suggests that Americans would do better than look to Europe for future solutions to our own problems. However attractive the European model may seem to our pundit class, the reality on the ground shows something more to be avoided than embraced.

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.