How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Northeast Ohio

Go to sleep, Captain Future, in your lair of art deco

You were our pioneer of progress, but tomorrow’s been postponed

Go to sleep, Captain Future, let corrosion close your eyes

If the board should vote to restore hope, we’ll pass along the lie

-The Secret Sound of the NSA, Captain Future

As near as I can tell, the term “Rust Belt” originated sometime in the mid-1980s. That sounds about right.

I originated slightly earlier, in 1972, at St. Thomas Hospital in Akron, Ohio, Rubber Capital of the World. My very earliest memory is of a day, sometime in the Summer of 1975, that my parents, my baby brother, and I went on a camping trip to Lake Milton, just west of Youngstown. I was three years old. To this day, I have no idea why, of all of the things that I could remember, but don’t, I happen to remember this one. But it is a good place to start.

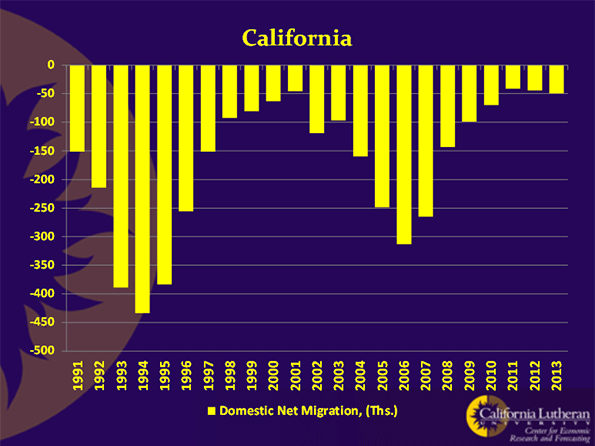

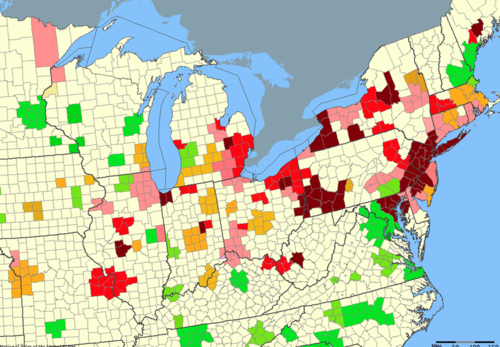

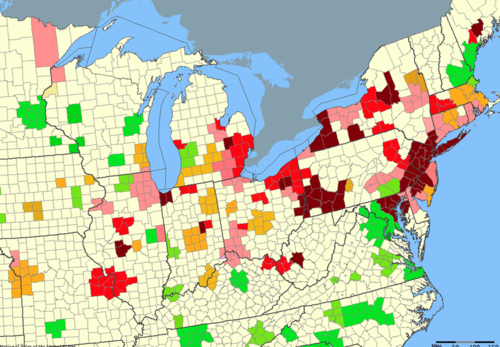

Image Source: Wikipedia: Change in total number of manufacturing jobs in metropolitan areas, 1954-2002. Dark red is very bad. Akron is dark red.

The memory is so vivid that I can still remember looking at the green overhead freeway signs along the West Expressway in Akron. Some of the signs were in kilometers, as well as in miles back then, due to an ill-fated attempt to convert Americans to the Metric system in the 1970s. I remember the overpoweringly pungent smell of rubber wafting from the smokestacks of B.F. Goodrich and Firestone. I recall asking my mother about it, and her explaining that those were the factories where the tires, and the rubber, and the chemicals were made. They were made by hard-working, good people – people like my Uncle Jim – but more on that, later.

When I was a little bit older, I would learn that this was the smell of good jobs; of hard, dangerous work; and of the way of life that built the modern version of this quirky and gritty town. It was the smell that tripled Akron’s population between 1910 and 1920, transforming it from a sleepy former canal-town to the 32nd largest city in America. It is a smell laced with melancholy, ambivalence, and nostalgia – for it was the smell of an era that was quickly coming to an end (although I was far too young to be aware of this fact at the time). It was sometimes the smell of tragedy.

We stopped by my grandparents’ house, in Firestone Park, on the way to the campground. I can still remember my grandmother giving me a box of Barnum’s Animals crackers for the road. She was always kind and generous like that.

Who were my grandparents? My grandparents were Akron. It’s as simple as that. Their story was Akron’s story. My grandfather was born in 1916, in Barnesboro, a small coal-mining town in Western Pennsylvania, somewhere between Johnstown, DuBois, and nowhere. His father, a coal miner, had emigrated there from Hungary nine years earlier. My grandmother was born in Barberton, in 1920. Barberton was reportedly the most-industrialized city in the United States, per-capita, at some point around that time.

They were both factory workers for their entire working lives (I don’t think they called jobs like that “careers” back then). My grandfather worked at the Firestone Tire & Rubber Company. My grandmother worked at Saalfield Publishing, a factory that was one of the largest producers of children’s books, games, and puzzles in the world. Today, both of the plants where they worked form part of a gutted, derelict, post-apocalyptic moonscape in South Akron, located between that same West Expressway and perdition. The City of Akron has plans for revitalizing this former industrial area. It needs to happen, but there are ghosts there…

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings,

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

-Percy Bysshe Shelley, Ozymandias

My grandparents’ house exemplified what it was to live in working-class Akron in the late 1970s and early 1980s. My stream-of-consciousness memories of that house include: lots of cigarettes and ashtrays; Hee-Haw; The Joker’s Wild; fresh tomatoes and peppers; Fred & Lamont Sanford; Archie & Edith Bunker; Herb Score and Indians baseball on the radio on the front porch; hand-knitted afghans; UHF/VHF; 3, 5, 8, and 43; cold cans of Coca-Cola and Pabst Blue Ribbon (back when the pop-tops still came off of the can); the Ohio Lottery; chicken and galuskas (dumplings); a garage floor that you could eat off of; a meticulously maintained 14-year-old Chrysler with 29,000 miles on it; a refrigerator in the dining room because the kitchen was too small; catching fireflies in jars; and all being right with the world.

I always associate the familiar comfort of that tiny two-bedroom bungalow with the omnipresence of cigarette smoke and television. I remember sitting there on May 18, 1980. It was my eighth birthday. We were sitting in front of the TV, watching coverage of the Mount St. Helens eruption in Washington State. I remember talking about the fact that it was going to be the year 2000 (the Future!) in just twenty years. It was an odd conversation for an eight year old to be having with adults (planning for the future already, and for a life without friends, apparently). I remember thinking about the fact that I would be 28 years old then, and how inconceivably distant it all seemed. Things seem so permanent when you’re eight, and time moves ever-so-slowly.

More often than not, when we visited my grandparents, my Uncle Jim and Aunt Helen would be there. Uncle Jim was born in 1936, in West Virginia. His family, too, had come to Akron to find work that was better-paying, steadier, and (relatively) less dangerous than the work in the coal mines. Uncle Jim was a rubber worker, first at Mohawk Rubber and then later at B.F. Goodrich. Uncle Jim also cut hair over at the most-appropriately named West Virginia Barbershop, on South Arlington Street in East Akron. He was one of the best, most decent, kindest people that I have ever known.

I remember asking my mother once why Uncle Jim never washed his hands. She scolded me, explaining that he did wash his hands, but that because he built tires, his hands were stained with carbon-black, which wouldn’t come out no matter how hard you scrubbed. I learned later, that it would take about six months for that stuff to leach out of your pores, once you quit working.

Uncle Jim died in 1983, killed in an industrial accident on the job at B.F. Goodrich. He was only 47. The plant would close for good about a year later.

It was an unthinkably tragic event, at a singularly traumatic time for Akron. It was the end of an era.

Times Change

My friend Della Rucker recently wrote a great post entitled The Elder Children of the Rust Belt over at her blog, Wise Economy. It dredged up all of these old memories, and it got me thinking about childhood, about this place that I love, and about the experience of growing up just as an economic era (perhaps the most prosperous and anomalous one in modern history) was coming to an end.

That is what the late 1970s and early 1980s was: the end of one thing, and the beginning of a (still yet-to-be-determined) something else. I didn’t know it at the time, but that’s because I was just a kid.

In retrospect it was obvious: the decay; the deterioration, the decomposition, the slow-at-first, and then faster-than-you-can-see-it unwinding of an industrial machine that had been wound-up far, far, too-tight. The machine runs until it breaks down; then it is replaced with a new and more efficient one – a perfectly ironic metaphor for an industrial society that killed the goose that laid the golden egg. It was a machine made up of unions, and management, and capitalized sunk costs, and supply chains, and commodity prices, and globalization. Except it wasn’t really a machine at all. It was really just people. And people aren’t machines. When they are treated as such, and then discarded as obsolete, there are consequences.

You could hear it in the music: from the decadent, desperately-seeking-something (escape) pulse of Disco, to the (first) nihilistic and (then) fatalistic sound of Punk and Post-Punk. It’s not an accident that a band called Devo came from Akron, Ohio. De-evolution: the idea that instead of evolving, mankind has actually regressed, as evidenced by the dysfunction and herd mentality of American society. It sounded a lot like Akron in the late 1970s. It still sounds a little bit like the Rust Belt today.

As an adult, looking back at the experience of growing up at that time, you realize how much it colors your thinking and outlook on life. It’s all the more poignant when you realize that the “end-of-an-era” is never really an “end” as such, but is really a transition to something else. But to what exactly?

The end of that era, which was marked by strikes, layoffs, and unemployment, was followed by its echoes and repercussions: economic dislocation, outmigration, poverty, and abandonment; as well as the more intangible psychological detritus – the pains from the phantom limb long after the amputation; the vertiginous sensation of watching someone (or something) die.

And it came to me then

That every plan

Is a tiny prayer to Father Time

As I stared at my shoes

In the ICU

That reeked of piss and 409

It sung like a violent wind

That our memories depend

On a faulty camera in our minds

‘Cause there’s no comfort in the waiting room

Just nervous paces bracing for bad news

Love is watching someone die…

-Death Cab For Cutie, What Sarah Said

But it is both our tragedy and our glory that life goes on.

Della raised a lot of these issues in her post: our generation’s ambivalent relationship with the American Dream (like Della, I feel the same unpleasant taste of rust in my mouth whenever I write or utter that phrase); our distrust of organizations and institutions; and our realization that you have to keep going, fight, and survive, in spite of it all. She talked about how we came of age at a time of loss:

not loss like a massive destruction, but a loss like something insidious, deep, pervasive.

It is so true, and it is so misunderstood. One of the people commenting on her blog post said, essentially, that it is dangerous to romanticize about a “golden age”; that all generations struggle; and that life is hard.

Yes, those things are all true. But they are largely irrelevant to the topic at hand.

There is a very large middle ground between a “golden age” and an “existential struggle”. The time and place about which we are both writing (the late 1970s through the present, in the Rust Belt) is neither. But it is undoubtedly a time of extreme transition. It is a great economic unraveling, and we are collectively and individually still trying to figure out how to navigate through it, survive it, and ultimately build something better out of it.

History is cyclical. Regardless of how enamored Americans, in general, may be with the idea, it is not linear. It is neither a long, slow march toward utopia, nor toward oblivion. When I look at history, I see times of relative (and it’s all relative, this side of paradise) peace, prosperity, and stability; and other times of relative strife, economic upheaval, uncertainty, and instability. We really did move from one of those times to the other, beginning in the 1970s, and continuing through the present.

The point that is easy to miss when uttering phrases like “life is hard for every generation” is that none of this discussion about the Rust Belt – where it’s been, where it is going – has anything to do with a “golden age”. But it has everything to do with the fact that this time of transition was an era (like all eras) that meant a lot (good and bad) to the people that lived through it. It helped make them who they are today, and it helped make where they live what it is today.

For those that were kids at the time that the great unraveling began (people like me, and people like Della) it is partially about the narrative that we were socialized to believe in at a very young age, and how that narrative went up in a puff of smoke. In 1977, I could smell rubber in the air, and many of my family members and friends’ parents worked in rubber factories. In 1982, the last passenger tire was built in Akron. By 1984, 90% of those jobs were gone, many of those people had moved out of town, and the whole thing was already a fading memory. Just as when a person dies, many people reacted with a mixture of silence, embarrassment, and denial.

As a kid, especially, you construct your identity based upon the place in which you live. The whole identity that I had built, even as a small child, as a proud Akronite: This is the RUBBER CAPITAL OF THE WORLD; this is where we make lots and lots of Useful Things for people all over the world; this is where Real Americans Do Real Work; this is where people from Europe, the South, and Appalachia come to make a Better Life for themselves; well, that all got yanked away. I couldn’t believe any of those things anymore, because they were no longer true, and I knew it. I could see it with my own two eyes. Maybe some of them were never true to begin with, but kids can’t live a lie the way that adults can. When the place that you thought you lived in turns out not to be the place that you actually live, it can be jarring and disorienting. It can even be heartbreaking.

We’re the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our great war is a spiritual war. Our great depression is our lives.

–Tyler Durden, Fight Club

I’m fond of the above quote. I was even fonder of it when I was 28 years old. Time, and the realization that life is short, and that you ultimately have to participate and do something with it besides analyze it as an outside observer, has lessened its power considerably. It remains the quintessential Generation X quote, from the quintessential Generation X movie. It certainly fits in quite well with all of this. But, then again, maybe it shouldn’t.

I use the phrase “Rust Belt Orphan” in the title of this post, because that is what the experience of coming of age at the time of the great economic unraveling feels like at the gut-level. But it’s a dangerous and unproductive combination, when coupled with the whole Gen-X thing.

In many ways, the Rust Belt is the “Generation X” of regions – the place that just doesn’t seem to fit in; the place that most people would just as soon forget about; the place that would, in fact, just as soon forget about itself; the place that, if it does dare to acknowledge its own existence or needs, barely notices the surprised frowns of displeasure and disdain from those on the outside, because they have already been subsumed by the place’s own self-doubt and self-loathing.

A fake chinese rubber plant

In the fake plastic earth

That she bought from a rubber man

In a town full of rubber plans

To get rid of itself

-Radiohead, Fake Plastic Trees

The whole Gen-X misfit wandering-in-the-Rust Belt-wilderness meme is a palpably prevalent, but seldom acknowledged part of our regional culture. It is probably just as well. It’s so easy for the whole smoldering heap of negativity to degenerate into a viscous morass of alienation and anomie. Little good can come from going any further down that dead-end road.

Whither the Future?

The Greek word for “return” is nostos. Algos means “suffering.” So nostalgia is the suffering caused by an unappeased yearning to return.

– Milan Kundera, Ignorance

So where does this all leave us?

First, as a region, I think we have to get serious about making our peace with the past and moving on. We have begun to do this in Akron, and, if the stories and anecdotal evidence are to be believed, we are probably ahead of the region as a whole.

But what does “making our peace” and “moving on” really mean? In many ways, I think that our region has been going through a collective period of mourning for the better part of four decades. Nostalgia and angst regarding the things that have been lost (some of our identity, prosperity, and national prominence) is all part of the grieving process. The best way out is always through.

But we should grieve, not so we can wallow in the experience and refuse to move on, but so we can gain a better understanding of who we are and where we come from. Coming to grips with and acknowledging those things, ultimately enables us to help make these places that we love better.

We Americans are generally not all that good at, or comfortable with, mourning or grief. There’s a very American idea that grieving is synonymous with “moving on” and (even worse) that “moving on” is synonymous with “getting over it”.

We’re very comfortable with that neat and tidy straight, upwardly-trending line toward the future (and a more prosperous, progressive, and enlightened future it will always be, world without end, Amen.)

We’re not so comfortable with that messy and confusing historical cycle of boom-and-bust, of evolution and de-evolution, of creation and destruction and reinvention. But that’s the world as we actually experience it, and it’s the one that we must live in. It is far from perfect. I wish that I had another one to offer you. But there isn’t one on this side of the Great Beyond. For all of its trials and tribulations, the world that we inhabit has one inestimable advantage: it is unambiguously real.

“Moving on” means refusing to become paralyzed by the past; living up to our present responsibilities; and striving every day to become the type of people that are better able to help others. But “moving on” doesn’t mean that we forget about the past, that we pretend that we didn’t experience what we did, or that we create an alternate reality to avoid playing the hand that we’ve actually been dealt.

Second, I don’t think we can, or should, “get over” the Rust Belt. The very phrase “get over it” traffics in denial, wishful thinking, and the estrangement of one’s self from one’s roots. Countless attempts to “get over” the Rust Belt have resulted in the innumerable short-sighted, “get rich quick” economic development projects, and public-private pyramid-schemes that many of us have come to find so distasteful, ineffective, and expensive.

We don’t have to be (and can’t be, even if we want to) something that we are not. But we do have to be the best place that we can be. This might mean that we are a smaller, relatively less-prominent place. But it also means that we can be a much better-connected, more cohesive, coherent, and equitable place. The only people that can stop us from becoming that place are we ourselves.

For a place that has been burned so badly by the vicissitudes of the global economy, Big Business, and Big Industry, we always seem to be so quick to put our faith in the Next Big Project, the Next Big Organization, and the Next Big Thing. I’m not sure whether this is the cause of our current economic malaise, or the effect, or both. Whatever it is, we need to stop doing it.

Does this mean that we should never do or dream anything big? No. Absolutely not. But it does mean that we should be prudent and wise, and that we should tend to prefer our economic development and public investment to be hyper-nimble, hyper-scalable, hyper-neighborhood-focused, and ultra-diverse. Fetishizing Daniel Burnham’s famous “Make no little plans…” quote has done us much harm. Sometimes “little plans” are exactly what we need, because they often involve fundamentals, are easier to pull-off, and more readily establish trust, inspire hope, and build relationships.

Those of us that came of age during the great economic unraveling and (still painful) transition from the Great American Manufacturing Belt to the Rust Belt might just be in a better position to understand our challenges, and to find the creative solutions required to meet them head-on. Those of us that stuck it out and still live here, know where we came from. We’re under no illusions about who we are or where we live. I think Della Rucker was on to something when she listed what we can bring to the table:

- Determination

- Long-game focus

- Understanding the depth of the pit and the long way left to climb out of it

- Resourcefulness

- Ability to salvage

- Expectation that there are no easy answers

- Disinclination to believe that everything will be all right if only we do this One Big Thing

When I look at this list, I see pragmatism, resilience, self-knowledge, survival skills, and leadership. It all rings true.

He wanted to care, and he could not care. For he had gone away and he could never go back any more. The gates were closed, the sun was gone down, and there was no beauty but the gray beauty of steel that withstands all time. Even the grief he could have borne was left behind in the country of illusion, of youth, of the richness of life, where his winter dreams had flourished.

“Long ago,” he said, “long ago, there was something in me, but now that thing is gone. Now that thing is gone, that thing is gone. I cannot cry. I cannot care. That thing will come back no more.”

-F. Scott Fitzgerald, Winter Dreams

So, let’s have our final elegy for the Rust Belt. Then, let’s get to work.

This post originally appeared in Jason Segedy’s Notes From the Underground on November 2, 2013.

Segedy is the Director of the Akron Metropolitan Area Transportation Study, the Metropolitan Planning Organization serving Akron, Ohio. As a native of Akron, and as an urban planner, he has a strong interest in the future of places throughout the Great Lakes region, and in the people that inhabit them.