The 1957 sci-fi classic The Incredible Shrinking Man reads like a Rust Belt city script. In it, the lead actor is afflicted with the anti-natural: shrinkage in a world of growth. The rest becomes existential. From the movie review blog “Twenty Four Frames”:

He hates being a scientific experiment and a spectacle for the media. He is no longer the everyday 1950′s image of the middle class, white picket fenced American man. Instead, he now fights for survival in his own house where everyday objects are now the enemy to his existence. Finally, he must face the biggest question of all. If he continues to shrink, will he eventually even exist?

Such is the mood behind revitalization efforts in shrinking city America, particularly the Rust Belt. There, population decline has been occurring for decades. It still occurs. The Cleveland metro lost nearly 83,000 people from 2000 to 2012. The Pittsburgh metro lost over 67,000. This is in contrast to the region’s “greenfield economies”—defined as “the set of conditions that flow from building on new territory or exploiting new markets vs. the redevelopment of old places”. For example, the geographically-expanding Columbus metro added 260,000 people from 2000 to 2012. The top feeder region into Columbus was Greater Cleveland.

The dynamics behind these demographic patterns are fairly intuitive. Population gains and losses are a factor of a region’s employment picture. Cleveland Fed economist Joel Elvery explains:

Urban economists like to divide a regional economy into two sectors: tradable and nontradable. The tradable sector produces goods and services that are sold outside of the region; the nontradable sector produces goods and services for use in the region…If the industries that make up the tradable sector are growing nationally, then the region will most likely grow. If the tradable sector is struggling, eventually the region will also struggle.

In the case of Cleveland, one of the region’s main tradable sectors is manufacturing. That said, technological advances in manufacturing means it takes less people to make a product. In the 1950s an auto worker made on average seven cars per year. A worker can make 28 today. The effect of the increased productivity is a loss of jobs. The effect of job loss is a declining population.

Put a fork in the Rust Belt, right?

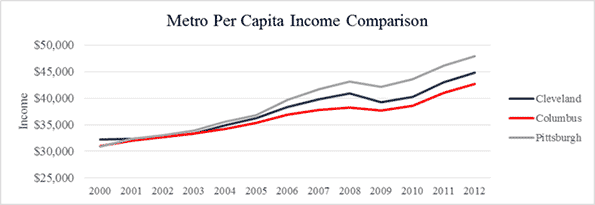

Not exactly. Figure 1 shows the metro per capita income for Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Columbus. The metros’ incomes were even around 2003, but then Pittsburgh and Cleveland began diverging from Columbus around 2005. Of importance here is that Pittsburgh and Cleveland have had higher per capita income growth than Columbus despite their declining population. This goes against the grain of traditional urban development thinking in which growth is god.

Figure 1: Source, US Bureau of Economic Analysis via Telestrian

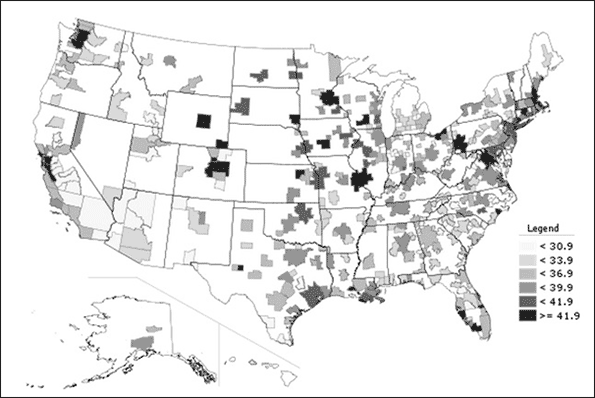

Looking at real per capita income at purchasing power parity (PPP), or income adjusted for inflation and how far a dollar goes in a given metro, the trends hold. The map below shows the real per capita income (PPP) for all metros for the United States. Notice Greater Cleveland and Greater Pittsburgh stand out, with values at or above $42,000 a year. In fact, in ranking the nation’s largest metros (over 1 million people), the highest real per capita metros were Hartford, Boston, and San Francisco, followed by Pittsburgh 6th and Cleveland 11th. Not bad for “dying” metros. Columbus clocked in at 28th, while peer Rust Belt metro Detroit was 44th out of 51.

Map: Map of real per capita personal income adjusted for inflation (in 2005 chained dollars) and regional purchasing power. In thousands of dollars (2011). Source, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis via Telestrian.

Why is greater per capita income growth happening in the Rust Belt compared to Columbus? We have to keep in mind that a rising per capita income is not necessarily associated with a robust economy, particularly for regions that have flat or declining populations. Specifically, a metro, such as Cleveland, can gain in per capita income simply due to a significant out-migration of low- and middle-income workers. Such a scenario could prove problematic if the area’s total personal income is decreasing across time, because then the overall economy is contracting.

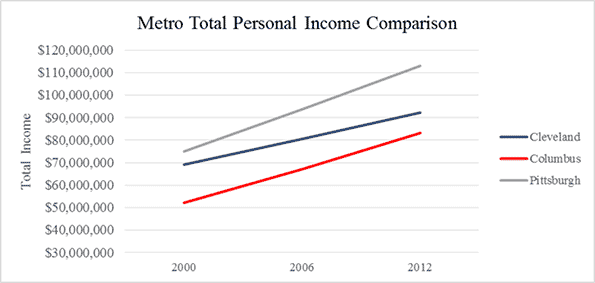

But this is not the case. Figure 2 shows the total personal income for the three metros from 2000 to 2012. Both Cleveland’s and Pittsburgh’s total personal income levels increase despite declining populations. This effect has been called “growth without growth” by the Brookings Institution, and it occurs when a workforce is becoming more educated and productive at the same time overall population declines.

Figure 2: Source, US Bureau of Economic Analysis

This is what is happening in the Cleveland metro. Data from a new study I co-authored with Jim Russell out of the Center for Population Dynamics at Cleveland State University showed that from 2000 to 2012, Greater Cleveland gained over 63,000 educated residents, while simultaneously losing nearly 74,000 residents without a college degree. Over two-thirds of this brain gain occurred between 2006 and 2012. The fastest growing cohort was for college-educated Greater Clevelanders 65 and plus—a 30% increase. The number of Greater Clevelanders with a college degree aged 25 to 34 increased by 23%. Conversely, the vast majority of the out-migration was made by people aged 35 to 44 without a 4-year degree.

This population dynamic is partly the result of Cleveland’s restructuring from a labor- into a knowledge-based economy. Specifically, growing tradable industries, like STEM and health care employment—which have driven job growth in Cleveland—are able to attract and retain skilled residents, whereas slower-growth industries are “pushing” less skilled workers elsewhere. Many of these non-degreed workers find a better return on investment in areas that are gaining in population, particularly if they are employed in the local consumer economy. Think laborers and much of the service class. This notion is supported by the fact that from 2000 to 2011, the average income of a person that moved from Greater Cleveland to Greater Columbus was $38,000 a year. Such a re-positioning of less-educated workers partly explains that while the Columbus metro is gaining on Greater Cleveland in total income, it is not the case with per capita income. Notes the Cleveland Fed: “Per capita income growth [in Columbus] is under increasing pressure to continue rising as population growth exceeds income growth”.

So yes, Cleveland shrinks. But it is not about brain drain, but about rational choice theory. And while population loss is troubling for any city, it is in many respects a necessary demographic result as a region like Greater Cleveland transitions from brawn- to brain-intensive work.

Think of this as a “one step at a time” approach to the existential plight that is the incredible shrinking city—meaning Cleveland’s migration needs are currently about quality, not quantity. This is because economic growth is not likely to be achieved through an increase in local consumption. Local jobs are created from emerging tradable industries, not vice versa—five service jobs are made for every new high-skill job in fact. And emerging industries are created via human capital, not consumer demand.

“Consumer demand does not necessarily translate into increased employment,” writes John Papola in Forbes. “That’s because ‘consumers’ don’t employ people. Businesses do.”

So where does Cleveland go from here?

It needs to look to Pittsburgh. The sister Rust Belt city has had a human capital formation that has been nothing short of astonishing. University of Pittsburgh economist Chris Briem calculated that the metro ranked fifth in the nation when it came to the percentage of young adult workers with a bachelor’s degree, behind only Boston, San Francisco, D.C., and Austin. What’s more, Greater Pittsburgh ranked first for the highest concentration of young adult workers with a graduate or professional degree.

“Change in the Pittsburgh economy is reflected in many ways,” writes Briem, “but probably no more profoundly than in the educational attainment of its workforce”.

Greater Cleveland doesn’t perform too shabbily either, ranking 17th in the nation in the number of young adult workers with a bachelor’s degree, and 7th in the nation for young workers with a graduate or professional degree, ahead of knowledge hub darlings Seattle and Austin.

In other words, Cleveland’s got something to build on: the quality of its young adult workforce. So instead of dumping money on brain drain boondoggles, or expending significant public expenditure on things like hotels and casinos that intend to drive economic growth from consumption on up, the region needs to pull out all the stops on growing a critical mass of talent. Because, as my colleague Jim Russell puts it, “talent is the new oil”.

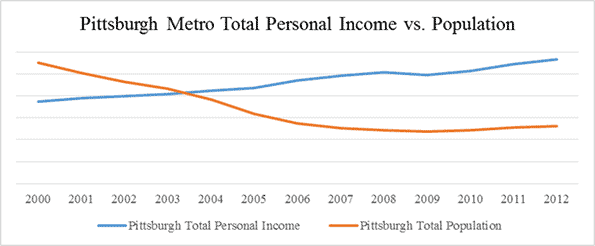

Eventually, once the region’s new economy sectors are revved up, then job growth for both skilled and less skilled work will increase, making the region amenable to population gain. This is the case in Pittsburgh, where population loss has recently turned into a slight gain after decades of decline (See Figure 3).

Figure 3: Source, American Community Survey, Bureau of Economic Analysis

But until that growth happens the Rust Belt will be stubbornly mired in its existential crisis. Shrinking, struggling, and wishing on silver bullets and outdoor chandeliers. But maybe there is room for measured hope. More exactly, we shrink therefore we are?

"I was continuing to shrink, to become… what? The infinitesimal? What was I? Still a human being?,” wonders the incredible shrinking man in the film’s closing monologue. “Or was I the man of the future?”

Well, considering what the cost of living is doing to the coasts, maybe the notion of Pittsburgh as the city of the future isn’t so farfetched. The Clevelands of the world would be wise to wager so, and then model accordingly.

Richey Piiparinen is a Senior Research Associate who leads the Center for Population Dynamics at the Levin College of Urban Affairs at Cleveland State University. His work focuses on regional economic development and urban revitalization.

Top image: Courtesy of Universal Pictures