As the recovery from the Great Recession stretches into its fifth year, the locus of economic momentum has shifted. In the early years of the recession, the cities that created the most jobs — sometimes the only ones — were either government- or military-dominated (Washington, D.C.; Kileen-Temple-Fort Hood, Texas), or were powered by the energy boom in Texas, Oklahoma and the northern Great Plains.

Now the recovery has shifted to a new group of cities that have benefited from the boom on Wall Street and the parallel IPO surge in Silicon Valley — call them asset inflation cities. Last year the S&P 500 clocked its biggest rise since 1997, helped by aggressive monetary easing by the Federal Reserve and a return to the stock market by investors who had retreated to the sidelines after the financial crisis. The high times have brought on a surge in IPOs: 2013 was the busiest year for public offerings in over a decade, and the pace has if anything quickened this year, with healthcare and technology offerings leading the way. M&A has also surged, with some very impressive valuations in the tech sector, such as Facebook’s $19 billion purchase of 50-person What’s App. The biggest beneficiaries employment-wise: the Bay Area, Silicon Valley and New York City.

View the Best Cities for Jobs 2014 List

Our rankings are based on short-, medium- and long-term job creation, going back to 2002, and factor in momentum — whether growth is slowing or accelerating. So the top of our list includes both cities that have had the most striking comebacks since the Great Recession as well as those that have consistently created jobs over the long haul. We have compiled separate rankings for large cities (nonfarm employment over 450,000), which are our focus this week, as well as medium-size cities (between 150,000 and 450,000 nonfarm jobs) and small cities (less than 150,000 nonfarm jobs) in order to make the comparisons more relevant to each category. (For a detailed description of our methodology, click here.) Small cities, as a rule, show more volatility than their larger counterparts since the decision of one major business to expand or contract can have an enormous effect on a relatively tiny employment base. (Check back next week for our ranking of mid-size and small cities).

Big Money, Big Gains

Yet even among the largest metropolitan areas, shifts in the economy can have a dramatic impact. This is clearly the case with the two metro areas that top our list this year, first-place San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, Calif. (aka Silicon Valley), where the number of jobs surged 4.3% last year, and San Francisco-San Mateo-Redwood City, where employment expanded 3.6%. Before the current tech boom, largely centered on social media companies, these metro areas were lagging badly. In 2010, San Jose ranked 47th on this list out of the 66 metro areas with more than 450,000 nonfarm jobs and San Francisco was 42nd.

The information sector has driven this remarkable change in fortunes. Since 2008, the number of information jobs in the San Jose area has risen 37% to 60,800, while in San Francisco, employment in that category has grown 28% to 52,300 jobs. This has been accompanied by strong increases in such high-wage fields as professional and business services, where Silicon Valley has clocked 10% growth, and San Francisco twice that, adding 42,500 jobs, since 2008.

The housing bubble helped to launch New York City from its doldrums a decade ago (it rose from 54th on our list of the Best Cities For Jobs in 2005 to 22th in 2008). In recent years, New York has been well served by Washington’s bailout of the financial sector, which accounts for roughly 15% of the metro area GDP — the Big Apple climbed to 10th place in our ranking in 2010 and to seventh this year. This is in good part a result of asset inflation; the number of finance jobs in New York has actually declined in recent years, but with a lot of extra spending money in the pockets of the city’s relatively high concentration of wealthy people, some jobs are being created. Most of the growth has been in hospitality, health and education and retail, fields that do not generally offer top salaries. New York City has also seen steady growth in information jobs — although at only a third the rate of Silicon Valley — as well as professional and business services.

Bring On The Usual Suspects

Many of the other metro areas at the top of our 2014 list have been adding jobs consistently over the past decade. Some are also beneficiaries of the high-tech boom, though mostly as a result of big West Coast companies deciding to site new offices in these attractive locations. In third place is perennial high-flyer Austin-Round Rock-San Marcos, Texas, where the number of jobs grew 4.1% last year, and 13.7% since 2008. Raleigh-Cary N.C. places fourth (3.9%/7.2% over the same time spans). These metro areas routinely attract people and companies from California and the Northeast with lower taxes and real estate costs that, on an income basis, are as much as half those in the asset-rich areas.

Unlike the asset-based economies, which ebb and flow with the markets, these and the other usual suspects have a record of consistent growth not only in jobs but also population. This reflects the more blue-collar economic foundation of many of these cities, based on energy, manufacturing and logistics — sectors that tend to create higher-paid blue- and white-collar jobs. Growth has continued in these areas throughout all the changes in the economy, which has encouraged long-term migration and investment.

Viewed over the last five years, for example, fifth-place Houston has expanded its total employment by 218,000 jobs, growing at the same rate as both the San Francisco and San Jose metro areas—an impressive feat given that it is almost 20 percent larger than the two Silicon Valley cities combined. But an arguably bigger difference can be seen in demographics. The Houston metro area’s population has grown over 50% faster since 2010 than the Bay Area regions, and roughly twice as fast as New York. Houston is on track this year to build more new housing units than the entire state of California. This combination of rapid population and job growth – the former itself a major source of jobs in construction and services — can be seen in places such as No. 6 Nashville-Franklin-Murfreesboro, Tenn.; No. 10 Denver-Aurora-Broomfield, Colo.; and No. 14 Charlotte-Gastonia-Round Hill, N.C.

The Sun Belt Bounces Back

Perhaps the biggest surprise on this year’s list is the resurgence of the Sun Belt metro areas that were hardest hit by the housing bust. Ever since, the Northeast-centric pundit class has been giddily predicting these cities’ demise. Strangled by high energy prices, cooked by record droughts, rejected by a new generation of urban-centric millennials, the Atlantic proclaimed this vast southern region to be where the American dream has gone to die.

But the data show that many of these metro areas are in the midst of a powerful comeback. Take Orlando-Kissimmee, Fla., ranked eighth this year, up 23 places from last year. Similarly Phoenix has risen 17 places from last year to 22nd and is way up from its 51st place ranking in 2010.

Perhaps even more surprising is the resurgence of 17th-place Riverside-San Bernardino, Calif., which ranked near the bottom of the big city table at 63rd in 2010. Now foreclosures have dropped and job growth has picked up. In fact, the Inland Empire is now doing considerably better in job creation than Southern California’s older urban regions, including Los Angeles-Long Beach (37th), Santa Ana-Anaheim-Irvine (34th) and San Diego-Carlsbad-San Marcos (32nd).

Bringing Up The Rear

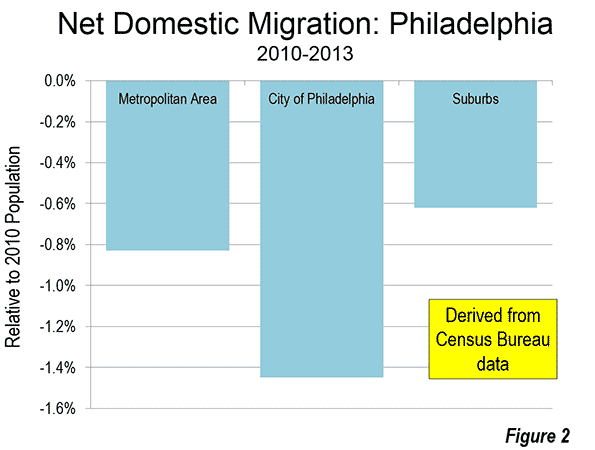

Many large cities continue to lag. Philadelphia, despite being close to New York and its considerable urban amenities, ranks 51st, with paltry 0.9% job growth since 2008. Not much better off, despite its connections to the Obama White House, is Chicago, which places 47th. Not only is the Windy City not adding many jobs (0.5% growth since 2008) but every county in the area, according to recent Census numbers, is losing migrants to other parts of the country.

But Chicago is certainly doing better than the host of old industrial cities that continue to dominate the nether reaches of our survey. These include last-place Camden, N.J.; second to last Detroit-Livonia-Dearborn, Mich.; Cleveland-Elyria- Mentor, Ohio (62nd), Kansas City, Mo. (61st), Newark-Union, N.J. (60th), and St. Louis (59th). All these cities, apart from Kansas City, have occupied the bottom of our list for nearly a decade now, and seem unlikely to move up in the immediate future.

View the Best Cities for Jobs 2014 List

What’s Next

It seems clear that as long as the tech and financial sectors retain their momentum, New York and the Bay Area should continue to fare well. But if asset growth slows, these areas could slip quickly.

The Texas cities and the other usual suspects are probably a better bet to continue to generate new jobs, but they too face challenges. If the economy slows down energy prices will follow, hampering growth in energy meccas like Houston, Dallas and San Antonio. A surge in interest rates could undermine the comeback of the Sun Belt cities, which remain highly dependent on housing and construction-related economic activity.

But overall, for reasons ranging from housing costs to business climate, we expect the usual suspects to remain high on our list of the best cities for jobs for years to come, in part due to their growing populations. What remains unknown is how the evolving industrial structure of the economy will affect the slower-growing cities along the coasts whose fortunes have tended to ebb and flow in recent years.

This story originally appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Michael Shires, Ph.D. is a professor at Pepperdine University School of Public Policy.

Photo: Market Street, San Francisco by Wendell Cox.