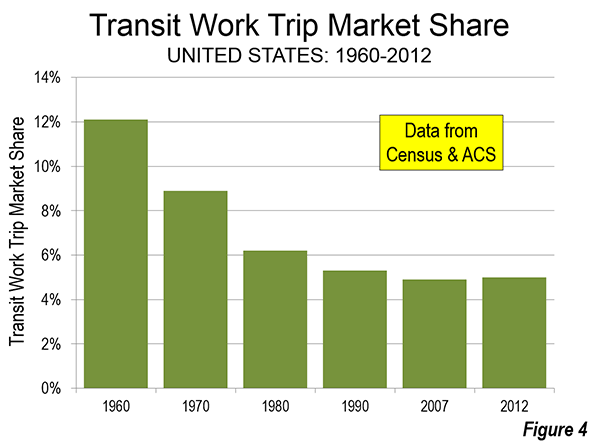

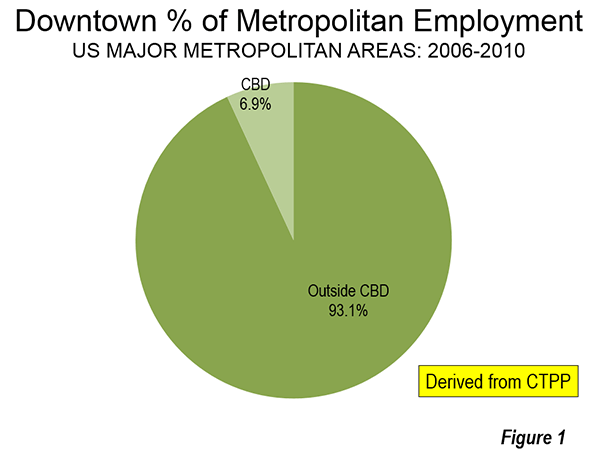

Photographs of downtown skylines are often the "signature" of major metropolitan areas, as my former Amtrak Reform Council colleague and then Mayor of Milwaukee (later President and CEO of the Congress of New Urbanism) John Norquist has rightly said. The cluster of high rise office towers in the central business district (CBD) is often so spectacular – certainly compared with an edge city development or suburban strip center – as to give the impression of virtual dominance. I have often asked audiences to guess how much of a metropolitan area’s employment is in the CBD. Answers of 50 percent to 80 percent are not unusual. In fact, the average is 7 percent in the major metropolitan areas (over 1,000,000) and reaches its peak at only 22 percent in New York (Figure 1), which sports the second largest business district in the world (after Tokyo).

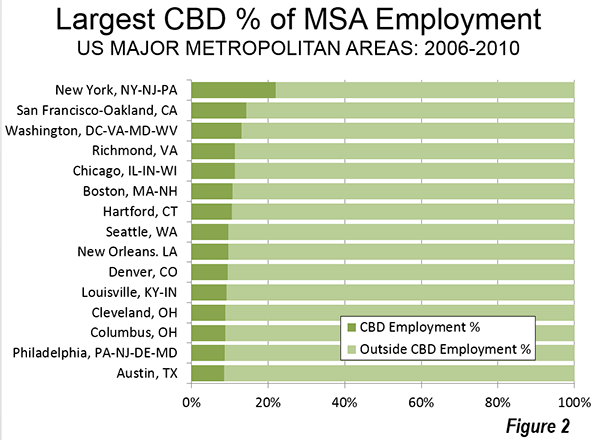

Only seven of the 52 major metropolitan areas have CBDs with 10 percent or more of employment. Some are much lower. For example, Los Angeles and Dallas have had some of the nation’s tallest skyscrapers outside New York or Chicago for decades, yet these downtowns have only 2.4 percent and 2.3 percent of their metropolitan area employment respectively (Figure 2).

This and similar information has been summarized in the third edition of Demographia Central Business Districts, which is based on the 2006-2010 Census Transportation Planning Package, a joint venture of the Census Bureau and the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). The two previous editions of the report summarized data from the 1990 and 2000 censuses.

The Declining Role of Downtown

Downtowns have become far less important than before World War II, when a large share of American households did not have access to automobiles and when employment was far more concentrated than today. Indeed, the highly concentrated American downtown area is "unique," as Robert Fogelson indicates in Downtown: Its Rise and Fall: 1880-1950, and could be easily located as the destination of the "street railways." Downtown was a product of transit and remains transit’s principal destination today. The concentrated US style CBD form is really quite rare outside other new world nations, such as Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. Some, but only a few Asian cities have also followed the example, most notably Shanghai, Hong Kong, Nanjing, Chongqing, Singapore, and Seoul.

The US, however, for all its role as originator of the downtown paradigm has also led the world in employment dispersion. This reflects the dominance in the US of automobiles. Dispersion is more amenable to mobility by the car, which dominates motorized mobility in virtually all major metropolitan areas of North America and Western Europe. This has led in the US to generally shorter work trip travel times and less traffic congestion, according to Tom Tom and Inrix. The continuing expansion of working at home could improve the situation even more.

New York has the largest CBD in the nation by far, with nearly 2,000,000 jobs. Chicago’s CBD (the Loop and North Michigan Avenue) has about one-quarter as many jobs (500,000) and Washington approximately 375,000. San Francisco, Boston and Philadelphia, also ranked among the nation’s transit "legacy cities," have between 200,000 and 300,000 jobs. Automobile oriented Houston and Atlanta are the largest otherwise, with Houston’s downtown being much more compact than Atlanta’s. Atlanta’s downtown has expanded strongly (and less densely) to the north and includes "Midtown" (Figure 3)

Transit is About Downtown

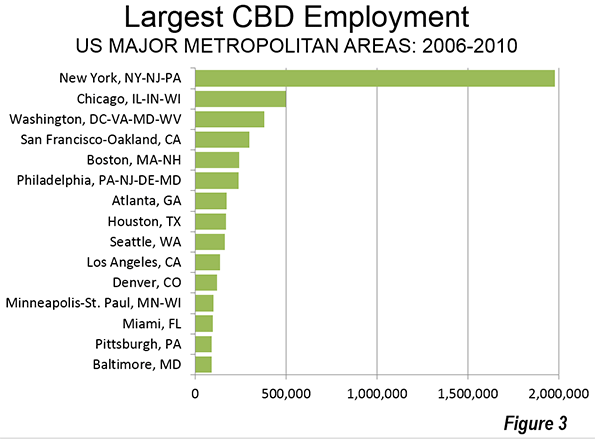

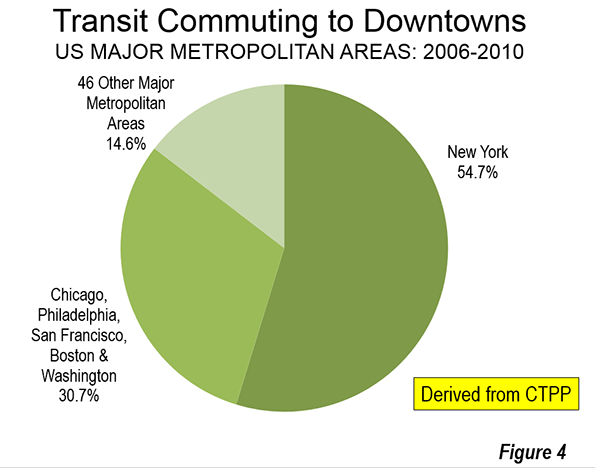

Transit is about downtown. Approximately 55 percent of transit commuting in the United States is to jobs in just six municipalities (not to be confused with metropolitan areas), which I have called transit’s "legacy cities." Most of that commuting is to the six downtown areas. Of course, the city of New York is dominant, which alone accounts for 55 percent of the country’s CBD transit commuting (Figure 4), with much of the balance in the other five legacy cities (Figure 4). Only 14 percent of the CBD commuting is to the other 46 smaller downtowns.

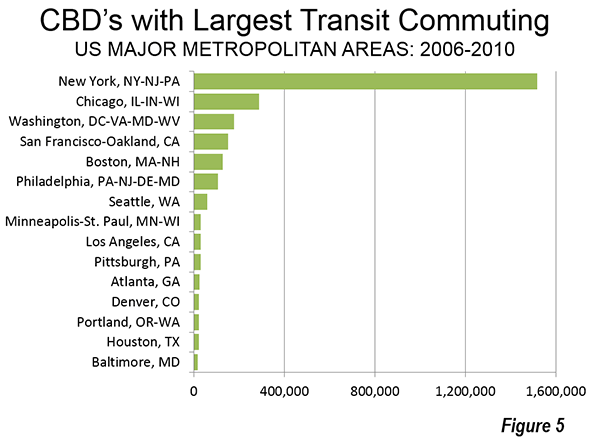

More than 1.5 million transit commuters converge on jobs in Manhattan every day. In the other five legacy cities, the figure ranges from 100,000 to 300,000 daily. All of the other central business districts draw fewer than 100,000 daily commuters. Seattle ranks 7th, at 60,000, and has double or more the CBD transit commuters of any of the other 44 CBDs (Figure 5).

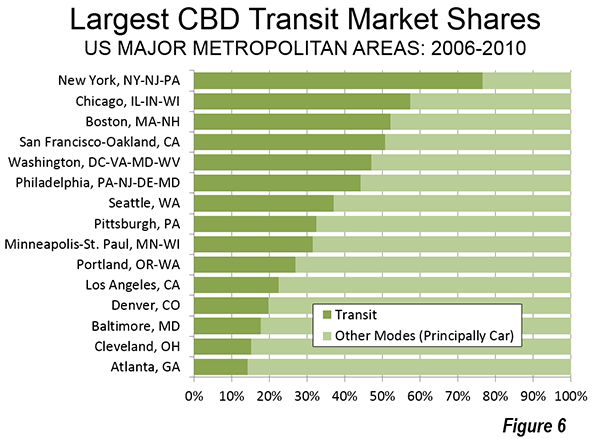

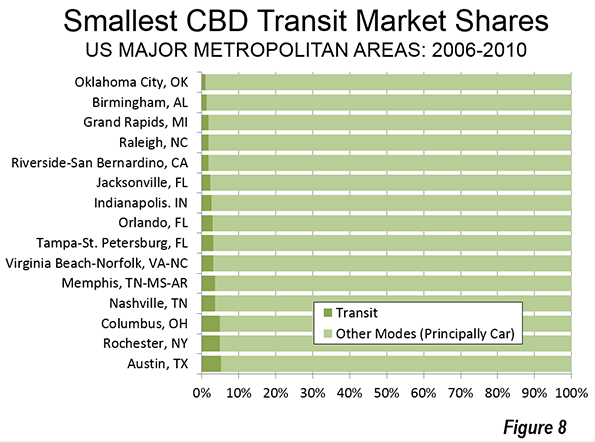

New York has by far the highest transit commuting share of any downtown in the nation. Approximately 77 percent of people who work in the New York central business district commute by transit. The other legacy cities post impressive market shares as well, though well below those of New York. The CBDs in Chicago, Boston, and San Francisco draw between 50 percent and 60 percent of their commuters by transit. Downtown Philadelphia and Washington attract more than 40 percent of their commuters by transit (Figure 6).

Transit is About Downtown II

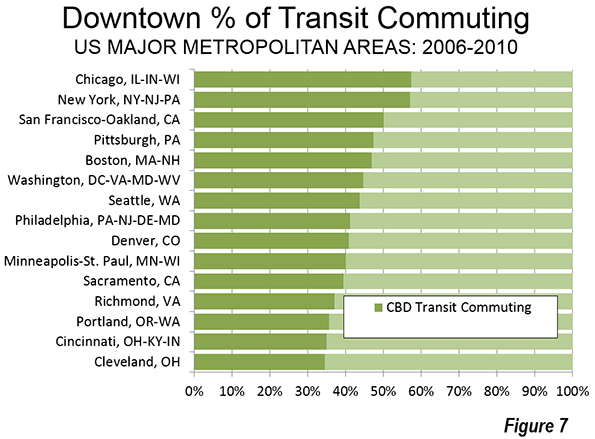

The importance of downtown to transit is also indicated by its predominance in transit commuting destinations. In the New York metropolitan area, with a transit market share of approximately 30 percent, 57 percent of all transit commuting is to downtown jobs. Chicago’s transit commuting is concentrated in downtown to a slightly greater degree than in New York. One half of all the transit commuting in the San Francisco metropolitan area is to downtown. The CBDs of Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington account for between 40 percent and 50 percent of all transit commuting in their downtown areas. Seattle and Pittsburgh also are in this range (Figure 7). Seven of the eight metropolitan areas with the largest transit market shares have a CBD commuting dominance of 40 percent or more (Pittsburgh is the exception).

The 52 major metropolitan area CBDs combined have less than five percent of the nation’s jobs. Elsewhere, downtowns and otherwise, the other 95 percent of American commuters use transit at only a three percent rate.

Other Employment Centers

In a new feature, Demographia Central Business Districts also provides data for selected employment centers other than the principal central business districts. These also include some surprises. For example, downtown Brooklyn, long since engulfed by the expansion of New York, has the second highest transit market share of any employment center identified other than New York, at 60 percent. Across the river, the Jersey City Waterfront area achieves a transit market share of more than 50 percent, greater than the downtowns of legacy cities Philadelphia and Washington.

Data on supplemental employment center and corridor data is selected and therefore not representative. It is notable that some employment corridors and centers have employment totals that dwarf those of the principal downtown areas in their respective metropolitan areas, such as Los Angeles, Portland, Dallas, and Kansas City.

With a few exceptions, the transit commuting shares for most of these selected centers and corridors is modest. Many are served by new rail systems, which are simply not up to the task of providing mobility to these dispersed centers. Nor can they provide the radial, high quality service that makes transit such a success in the six legacy city downtowns. For example, the Dallas light rail system provides service along virtually the entire US-75 corridor from north of downtown to Plano. Transit’s share of commutes in this corridor is only 2 percent, far below the downtown Dallas share of 14 percent and the legacy city downtown average of 65 percent.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He was appointed to the Amtrak Reform Council to fill the unexpired term of Governor Christine Todd Whitman and has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.