This is the second of a two-part series discussing Charles Mongomery’s Happy City. Read part one here.

‘The system that built sprawl’

Montgomery faces the hurdle of explaining why, if low-density suburbs cause unhappiness, so many millions of people, over so many decades, across several countries, flocked to that way of life. As he writes, ‘since 1940, almost all urban growth has actually been suburban.’ He must account for this fact, even though it means little to him personally. For the green-tinged intelligentsia, working and middle-class people are pawns who rarely think for themselves.

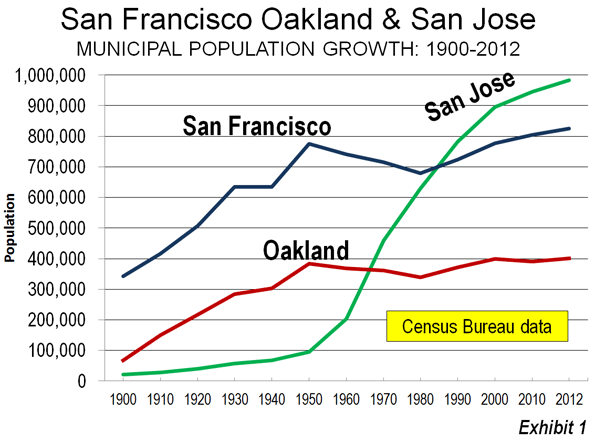

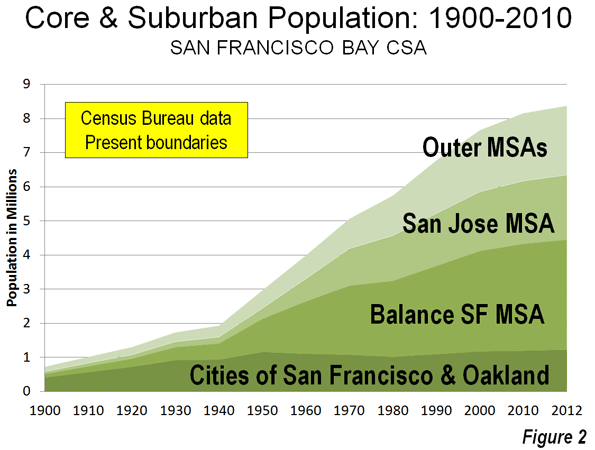

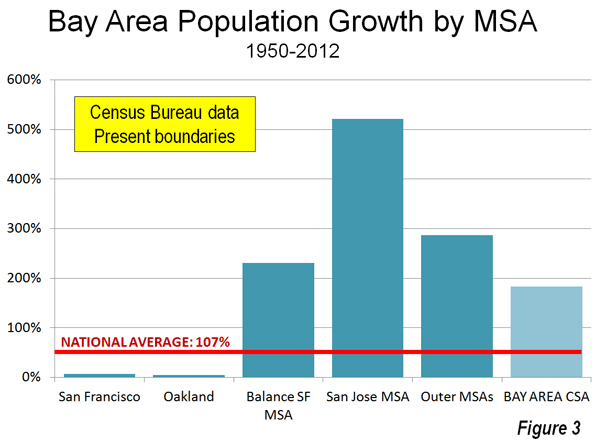

Still, in Montgomery’s case the hurdle is high, since his objections to dispersion go much further than conventional gripes about fragile economic foundations. Happy City does peddle the myth, in passing, that the financial crisis brought suburbanisation to a crashing halt. There’s an assertion that ‘census data in 2010/2011 showed that major American cities showed more growth than their suburbs’, and a hope this points to forces ‘systemic and powerful enough to permanently alter the course of urban history’. Montgomery even compares buying a detached home on the urban edge to ‘gambling on oil futures and global geopolitics’. As it turns out, he misconstrues the available data. Suburbanisation barely missed a beat in the United States and continues in earnest.

Montgomery’s essential point, though, is that suburban life is contrary to deep-seated human yearnings. This endows him with an even more patronising attitude to working people than his forerunners Richard Florida – who endorses the book – and Edward Glaeser. One line of argument in Happy City, which also features in Glaeser’s Triumph of the City, claims dispersion was forced on people by greedy land owners and property developers in cahoots with weak-kneed or compromised politicians and officials.

He puts it his way: ‘sprawl, as an urban form, was laid-out, massively subsidized and legally mandated long before anyone actually decided to buy a house there … it is as much the result of zoning, legislation and lobbying as a crowded city block.’ In another chapter, Montgomery warns of the challenge for pro-density New Urbanism: ‘the system that built sprawl – huge state subsidies, financial incentives and powerful laws – is still in place.’ Popular preferences don’t even rate a mention. Similar comments appear throughout the book, adding up to an audacious feat of historical revisionism.

The standard interpretation of urban evolution, from the walking city to the monocentric and then polycentric metropolis, places breakthroughs in transport technologies first, most notably railways, streetcars (trams) and affordable motor vehicles, followed by mass shifts in transportation modes and population movements second, with land owners and politicians ready to exploit the new conditions. Of course, transportation technologies have such a powerful impact because of pent up demand for space and lower densities.

Essentially, Montgomery reverses the causative sequence, claiming government and business interests dragged people to the fringes and this induced a transformation of transportation modes, which may or may not have been viable under prevailing technologies. This anomalous theory puts him at odds with some of the most recognised urban thinkers:

- Lewis Mumford in The City in History: ‘what has happened to the suburb is now a matter of historic record … as soon as the motor car became common, the pedestrian scale of the suburb disappeared …’

- Peter Hall in Cities in Civilization, discussing Los Angeles: ‘the car was doing more than decentralize; it was decentralizing in a new way’.

- Robert Bruegmann in Sprawl: A Compact History: ‘families wishing to live at lower densities could be seen as the primary cause of the growth in … the railroad, public transportation and finally the automobile industry … each of these means of transportation did, in fact, give families increased mobility.’

- Joel Kotkin in The City: A Global History: ‘as automobile registrations soared in the 1920s, suburbanization across the rest of [the United States] also picked up speed, with suburbs growing at twice the rate of cities.’

- Shlomo Angel in Planet of Cities: ‘a third and more radical transformation, from the monocentric to the polycentric city, began in the middle decades of the twentieth century with the rapid increase in the use of cars, buses, and trucks.’

Such quotes can be piled up all day long.

Happy City is open to the same criticism as Glaeser’s book, namely that as a matter of chronology, urban dispersion took off before the interstate highway system, tax deductibility of home mortgage interest, the relative decline of inner-city schools, many development controls, and other factors cited by both as having pushed Americans to the periphery. In Downtown: Its Rise and Fall 1880-1950, Robert Fogelson explains that ‘by the mid and late 1920s, however, some Americans had come to the conclusion that the centrifugal forces were beginning to overpower the centripetal forces – or, in other words, that the dispersal of residences might well lead in time to the decentralization of business.’ And suburbs have been popular in countries other than the US, like Australia, where these sorts of factors are absent.

Blinded by science

For his part, Montgomery envisages an alternative past, in which demands for space and mobility hardly figure. ‘Well, the path that led … to today’s sprawl was not straight’, he writes, ‘it meandered back and forth between pragmatism, greed, racism and fear.’ Rewriting history may be audacious, but that’s just the beginning. The book doesn’t stop at denouncing suburbanisation as a form of organised compulsion. Montgomery’s ultimate purpose, drawing on ‘happiness science’, is to expose suburban life as a mass delusion. ‘We need to identify the unseen systems that influence our health and control our behaviour’, he writes.

Much of Happy City is devoted to a succession of studies and experiments by a range of neuroscientists, psychologists and behavioural economists on the conditions that stimulate feelings of well-being and contentment. Montgomery focuses on research into different spatial environments: densely or sparsely populated, high-rise or street-level, crowded or uncrowded, mixed-use or homogenous, auto-dependent or walkable, near or far from nature, and so on.

Many people have no clue that their deeper inclinations are out of synch with their surroundings, he maintains, painting a less than flattering portrait of human nature. ‘The more psychologists and [behavioural] economists examine the relationship between decision-making and happiness,’ he repeats in various ways, ‘the more they realize … we make bad choices all the time … in fact we screw up so systematically …’

Building a case that most of us are hobbled by delusions, Montgomery delights in claiming ‘we are far less rational in our decisions than we sometimes like to believe …’, and ‘we regularly respond to our environment in ways that seem to bear little relation to conscious thought or logic.’ Personal motives can be reduced to a stew of physiological and chemical stimuli, all summed up in a single paragraph:

Neuroscientists have found that environmental cues trigger immediate responses in the human brain even before we are aware of them. As you move into a space, the hippocampus, the brain’s memory librarian, is put to work immediately … it also sends messages to the brain’s fear and reward centres … it’s neighbour, the hypothalamus, pumps out a hormonal response … before most of us have decided if a place is safe or dangerous … places that seem too sterile or too confusing can trigger the release of adrenaline and cortisol, the hormones associated with fear and anxiety … places that seem familiar … are more likely to activate hits of feel-good serotonin, as well as the hormone that … promotes feelings of interpersonal trust: oxytocin.

Nowhere is it acknowledged that if rational choice is devalued, people might end up being treated less like autonomous citizens and more like laboratory rats. Happiness ‘can’t be summed up by the number of things we produce or buy’, the book insists, ‘but the firing synapses of our brains, the chemistry of our blood …’

Montgomery proceeds to grab hold of anything that discredits the real-life choices of suburbia’s teeming millions. One of many concepts he takes from neuroscience is ‘information propagation’. By operation of the hippocampus and other parts of the brain, we are told, our ‘concept of the right house, car or neighbourhood might be as much a result of happy moments from our past or images that flood us in popular media as of any rational analysis.’ From psychology he borrows the concept of ‘adaptation’, described as a ‘characteristic that exacerbates such bad decision-making [namely] the uneven process by which we get used to things.’

He considers these important explanations for the appeal of suburban lifestyles when denser neighbourhoods are better for physical and mental health, at least according to his interpretation of studies and experiments on walking, cycling, social encounters, community activities, public space, streetscapes, grid planning, on-street parking and traffic velocity.

But his method of selecting a body of research, cobbling the results together, and equating this to the preconditions for a happy life, suffers from a fallacy of composition ─ the error of inferring that something is true of the whole from the fact that it is true of some part of the whole. Although Montgomery claims ‘most people, in most places, have the same basic needs and most of the same desires’, it doesn’t follow that research findings on parts of life should add up to a real whole life.

Kirk Schneider, a prominent American psychologist, writes in Psychology Today that ‘prevailing studies of happiness … represent but a circumscribed range of how such phenomena are actually experienced on the ground, so to speak, in people’s everyday worlds.’ Schneider cautions that ‘those things represent only slices of life, not life itself.’

There’s no reason why urban planning should start from abstract assumptions drawn from a bunch of controlled experiments, rather than from masses of people weighing up their full, lived experience.

In this and other ways, the book succumbs to a disturbing strain of authoritarianism. History teaches us to beware a state that deals with people through the prism of theories which second-guess their inner thoughts and feelings, rather than according to their outward conduct. Freedoms are at risk whenever powerful functionaries claim to know what people are thinking, because of ‘false consciousness,’ ethnic stereotypes, biological determinism, or whatever. And Montgomery is no freedom-fighter: ‘we are pushed and pulled according to the systems in which we find ourselves, and certain geometries ensure that none of us are as free as we might think.’

‘Make them feel rich’

In the end, Happy City fails to prove the assertions trumpeted in its opening pages. It fails to produce any direct evidence connecting flatlining assessments of well-being or rising rates of depressive illness to ‘sprawl’. Nor is there any indirect evidence from which a connection can be inferred. Just as research on parts of life don’t add up to a whole real life, neither can studies and experiments finding discontent in particular conditions translate to generalised disenchantment with a whole way of life.

Montgomery’s style is to fill the gaps with a series of conveniently chosen anecdotes and vignettes, some designed to trash suburbia and others to wrap a glowing aura around transit-oriented density. Randy Straussner’s super-commuting horror story, which never goes away, is an example of the former. But the star of the book, and prominent case of the latter, is ‘The Mayor of Happy’.

At the helm of impoverished Bogota between 1998 and 2001, Enrique Penalosa cancelled a highway expansion plan, used the funds for hundreds of miles of cycle paths, hiked fuel taxes by 40 per cent, banned drivers from commuting by car more than three times a week, introduced car-free days, dedicated a new chain of parks and pedestrian plazas, and built the city’s first rapid transit system. This made him a guru to green urbanists like Montgomery, who was inspired to write Happy City.

‘We might not be able to fix the economy’, Penalosa is quoted as saying in the book, ‘we might not be able to make everyone as rich as Americans … but we can design the city to give people dignity, to make them feel rich.’ Confronting an unemployment rate of 18 per cent when Penalosa left office, however, many Bogotans would have longed for the real thing.

John Muscat is a co-editor of The New City, where this piece first appeared.