The startup scene today, and by ‘scene’ I’m sweeping a fairly catholic brush over a large swath of people – observers, critics, investors, entrepreneurs, ‘want’repreneurs, academics, techies, and the like – seems to be riven into two camps.

On one side stand those who believe that entrepreneurs have stopped chasing and solving Big Problems – capital B, capital P: clean energy, poverty, famine, climate change, you name it. I needn’t replay their song here; they’ve argued their cases far more eloquently elsewhere. In short, they contend that too many brains and dollars have been shoveled into resolving what I call ‘anti-problems’ – interests usually centered about food or fashion or ‘social’ or gaming. Something an anti-problem company might develop is an app that provides restaurant recommendations based on your blood type, a picture of your childhood pet, the music preferences of your 3 best friends, and the barometric pressure of the nearest city beginning with the letter Q. (That such an app does not yet exist is reminder still of how impoverished a state American scientific education has descended. Weep not! We redouble our calls for more STEM funding.)

On the other side stand those who believe that entrepreneurs have stopped chasing and solving Big Problems – capital B, capital P – that there are too many folks resolving anti-problems… BUT just to be on the safe side, the venture capitalists should keep pumping tons of money into those anti-problem entrepreneurs because you never know when some corporate leviathan – Google, Facebook, Yahoo! – will come along and buy what yesterday looked like a nonsense app and today is still a nonsense app, but a nonsense app that can walk a bit taller, held aloft by the insanities of American exceptionalism. For not only is our sucker birthrate still high in this country (one every minute, baby!), but our suckers are capitalists bearing fat checks.

On the other other side, a side that receives scant attention, scanter investment, is where big problems – little b, little p – reside. Here, you’ll find a group I’ll refer to as the unexotic underclass. It’s rather quiet in these parts, except during campaign season when the politicians stop by to scrape anecdotes off the skin of someone else’s suffering. Let’s see who’s here.

To your left are single mothers, 80% of whom, according to the US Census, are poor or hovering on the nasty edges of working poverty. They are struggling to raise their kids in a country that seems to conspire against any semblance of proper rearing: a lack of flexibility in the workplace; a lack of free or affordable after-school programs; an abysmal public education system where a testing-mad, criminally-deficient curriculum is taught during a too-short school day; an inescapable lurid wallpaper of sex and violence that covers every surface of society; a cultural disregard for intelligence, empathy and respect; a cultural imperative to look hot, spend money and own the latest “it”-device (or should I say i-device) no matter what it costs, no matter how little money Mum may have.

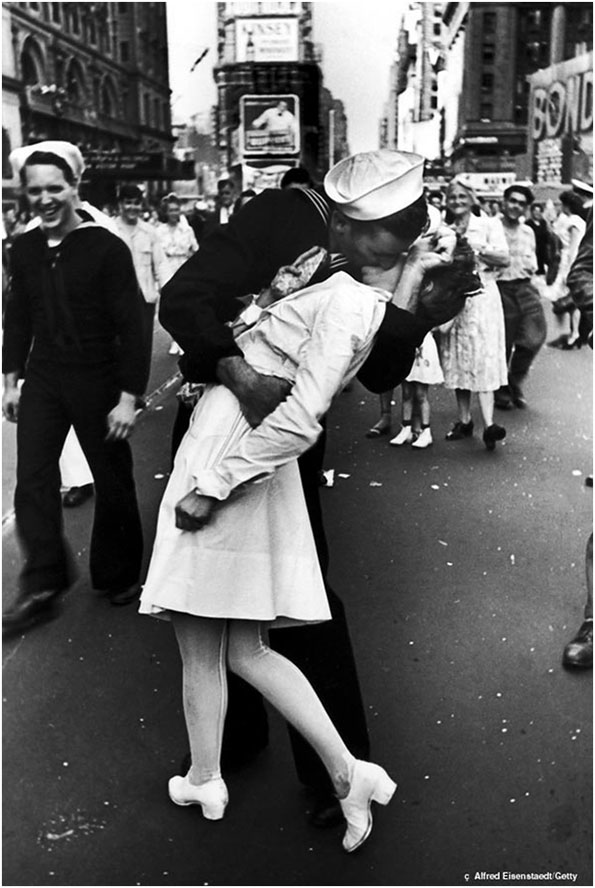

Slightly to the right, are your veterans of two ongoing wars in the Middle East. Wait, we’re at war? Some of these veterans, having served multiple tours, are returning from combat with all manner of monstrosities ravaging their heads and bodies. If that weren’t enough, welcome back, dear vets, to a flaccid economy, where your military training makes you invisible to an invisible hand that rewards only those of us who are young and expensively educated.

Welcome back to a 9-month wait for medical benefits. According to investigative reporter Aaron Glantz, who was embedded in Iraq, and has now authored The War Comes Home: Washington’s Battle against America’s Veterans, 9 months is the average amount of time a veteran waits for his or her disability claim to be processed after having filed their paperwork. And by ‘filed their paperwork,’ I mean it literally: veterans are sending bundles of papers to some bureaucratic Dantean capharnaum run by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, where, by its own admission, it processes 97% of its claims by hand, stacking them in heaps on tables and in cabinets.

In the past 5 years, the number of vets who’ve died before their claim has even been processed has tripled. This is America in 2013: 40 years ago we put a man on the moon; today a young lady in New York can use anti-problem technology if she wishes to line up a date this Friday choosing only from men who are taller than 6 feet, graduated from an Ivy, live within 10 blocks of Gramercy, and play tennis left-handed…

…And yet, veterans who’ve returned from Afghanistan and Iraq have to wait roughly 270 days (up to 600 in New York and California) to receive the help — medical, moral, financial – which they urgently need, to which they are honorably entitled, after having fought our battles overseas.

Technology, indeed, is solving the right problems.

Let’s keep walking. Meet the people who have the indignity of being over 50 and finding themselves suddenly jobless. These are the Untouchables of the new American workforce: 3+ decades of employment and experience have disqualified them from ever seeing a regular salary again. Once upon a time, some modicum of employer noblesse oblige would have ensured that loyal older workers be retained or at the very least retrained, MBA advice be damned. But, “A bas les vieux!” the fancy consultants cried, and out went those who were ‘no longer fresh.’ As Taylor Swift would put it, corporate America and the Boomer worker “are never ever getting back together.” Instead bring in the young, the childless, the tech-savvy here in America, and the underpaid and quasi-indentured abroad willing to work for slightly north of nothing in the kinds of conditions we abolished in the 19th century.

For, in the 21st century, a prosperous American business is a soaring 2-storied cake: 1 management layer at top thick with perks, golden parachutes, stock options, and a total disregard for those beneath them; 1 layer below of increasingly foreign workers (If you’re lucky, you trained these people before you were laid off!), who can’t even depend on their jobs because as we speak, those sameself consultants – but no one that we know of course — are scouring the globe for the cheapest labor opportunities, fulfilling their promise that no CEO be left behind.

Above all of this, the frosting on the cake, the nec plus ultra of evolutionary corporate accomplishment: the Director of Social Media. This is the 20-year old whose role it is to “leverage social media to deliver a seamless authentic experience across multiple digital streams to strategic partners and communities.” In other words, this person gets paid six figures to send out tweets. But again, no one that we know.

Time and space and my own sheltered upbringing defend me from giving you the whole tour of the unexotic underclass, but trust that it is big, and only getting bigger.

___________________________________

Now, why the heck should any one care? Especially a young entrepreneur-to-be. Especially a young entrepreneur-to-be whose trajectory of nonstop success has placed him or her leagues above the unexotic underclass. You should care because the unexotic underclass can help address one of the biggest inefficiencies plaguing the startup scene right now: the flood of (ostensibly) smart, ambitious young people desperate to be entrepreneurs; and the embarrassingly idea-starved landscape where too many smart people are chasing too many dumb ideas, because they have none of their own (or, because they suspect no one will invest in what they really want to do). The unexotic underclass has big problems, maybe not the Big Problems – capital B, capital P – that get ‘discussed’ at Davos. But they have problems nonetheless, and where there are problems, there are markets.

The space that caters to my demographic – the cushy 20 and 30-something urbanites – is oversaturated. It’s not rocket science: people build what they know. Cosmopolitan, well-educated young men and women in America’s big cities are rushing into startups and building for other cosmopolitan well-educated young men and women in big cities. If you need to plan a trip, book a last minute hotel room, get your nails done, find a date, get laid, get an expert shave, hail a cab, buy clothing, borrow clothing, customize clothing, and share the photos instantly, you have Hipmunk, HotelTonight, Manicube, OKCupid, Grindr, Harry’s, Uber, StyleSeek, Rent the Runway, eshakti/Proper Cloth and Instagram respectively to help you. These companies are good, with solid brains behind them, good teams and good funding.

But there are only so many suit customisation, makeup sampling, music streaming, social eating, discount shopping, experience curating companies that the market can bear. If you’re itching to start something new, why chase the nth iteration of a company already serving the young, privileged, liberal jetsetter? If you’re an investor, why revisit the same space as everyone else? There is life, believe me, outside of NY, Cambridge, Chicago, Atlanta, Austin, L.A. and San Fran.

It’s where the unexotic underclass lives. It’s called America. This underclass is not some obscure niche market. Take the single mothers. Per the US Census Bureau, there are 10 million of them today; and an additional 2 million single fathers. Of the single mothers, the majority is White, 1 in 4 is Hispanic, and 1 in 3 is Black. So this is a fairly large and diverse group.

Take the veterans. (I will beat the veteran drum to death.) According to the VA’s latest figures, there are roughly 23 million vets in the United States. That number sounds disturbingly high; that’s almost 1 in 10 Americans. Entrepreneurs and investors like big numbers. Other groups you could include in the underclass: ex-convicts, many imprisoned for petty drug offenses, many released for crimes they never even committed. How does an ex-convict get back into society? And navigate not just freedom, but a transformed technological landscape? Another group, and this one seems to sprout in pockets of affluence: people with food allergies. Some parents today resort to putting shirts and armbands on their kids indicating what foods they can or can’t eat. Surely there’s a better fix for that?

Maybe you could fix that.

___________________________________

Why do I call this underclass unexotic? Because, those of us, lucky enough to be raised in comfortable environs – well-schooled, well-loved, well-fed – are aware of only 2 groups: those at the very bottom and those at the very top.

We have clear notions of what the ruling class resembles – its wealth, its connections, its interests. Some of you reading this will probably be part of the ruling class before you know it. Some of you probably already are. For the 1% aspirants (and there’s no harm in having such aspirations), hopefully by the time you get there, you will have found meaningful problems to solve – be they big, or Big.

We have clear ideas of what the exotic underclass looks like because everyone is clamoring to help them. The exotic underclass are people who live in the emerging and third world countries that happen to be in fashion now -– Kenya, Bangladesh, Brazil, South Africa. The exotic underclass are poor Black and Hispanic children (are there any other kind?) living in America’s urban ghettos. The exotic underclass suffer from diseases that have stricken the rich and famous, and therefore benefit from significant attention and charity.

On the other hand, the unexotic underclass, has the misfortune of being insufficiently interesting. These are the huddles of Whites – poor, rural working class – living in the American South, in the Midwest, in Appalachia. In oh-so-progressive Northeast, we refer to them as ‘hicks’ and ‘hillbillies’ and ‘trailer trash,’ because apparently, this is the one demographic that American manners have forgotten.

The unexotic underclass are the poor in Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, who just don’t look foreign enough for our taste. Anyone who’s lived in a major European city can attest to the ubiquity of desperate Roma families, arriving from Bulgaria and Romania, panhandling in the streets and on the subways. This past April, the employees of the Louvre Museum in Paris went on strike because they were tired of being pickpocketed by hungry Roma children. But if you were to go to Bulgaria to volunteer or to start a social enterprise, how would the folks back on Facebook know you were helping ‘the poor?’ if the poor in your pictures kind of looked like you?

And of course, the biggest block of the unexotic underclass are the ones I alluded to earlier: that vast, suffocating mass right here in in America. We don’t notice them because they don’t get by on $1 a day. We don’t talk about them because they don’t make $1 billion a year. The only place where they’re popular is in Washington, D.C. where President Obama and his colleagues in Congress can can use members of the underclass to spice up their stump speeches: “Yesterday, I met a struggling family out in yadda yadda yadda…” But there’s only so much Washington can do to help out, what with government penniless and gridlocked, and its elected officials occupying a caste of selfishness, cowardice and spite, heretofore unseen in American politics.

__________________________________

If you’re an entrepreneur looking for ideas, consider looking beyond the city-centric, navel-gazing, youth-obsessed mainstream. That doesn’t mean you need to fly to the end of the world. Chances are there are more people addressing the Big Problems of slum dwellers in Calcutta, Kibera or Rio, than are tackling the big problems of hardpressed folks in say, West Virginia, Mississippi or Louisiana.

To be clear, I’m not painting the American South as the primary residence of all the wretched of the earth. You will meet people down there who are just as intelligent and cultured and affluent as we pretend everyone up North is.

Second, I’m not pitting the unexotic against the exotic. There is nothing easy or trendy about the work being done by the brave innovators on the ground in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Some examples of that work: One Earth Designs which helps deliver clean energy and heating solutions to communities in rural China; Sanergy, which is bringing low-cost sanitation to Kenya’s poorest slums; Samasource, which provides contract work to youth and women in Haiti, Ghana, Kenya, Uganda and India. These are young startups with young entrepreneurs who attended the same fancy schools we all know and love (MIT, Harvard, Yale, etc.), who lived in the same big cities where we all congregate, and worked in the same fancy jobs we all flocked to post-graduation. Yet, they decided they would go out and tackle Big Problems – capital B, capital P. We need to encourage them, even if we could never imitate them.

If we can’t imitate them,and we’re not ready for the challenges of the emerging market, and we have no new ideas to offer, then maybe there are problems, right here in America for us to solve…The problems of the unexotic underclass.

____________________________________

Now, I can already hear the screeching of meritocratic, Horatio Algerian Silicon Valley,

“What do we have to do with any of this? The unexotic underclass has to pull itself up by its own bootstraps! Let them learn to code and build their own startups! What we need are more ex-convicts turned entrepreneurs, single mothers turned programmers, veterans turned venture capitalists!

The road out of welfare is paved with computer science!!!”

Yes, of course.

There’s nothing wrong with the entrepreneurship-as-salvation gospel. Nothing wrong with teaching more people to code. But it’s impractical in the short term, and misses the greater point in the long term: We shouldn’t live in a universe of solipsistic startups… where I start a company and produce things only for myself and for people who resemble me. Let’s be honest. Very few of us are members of this unexotic underclass. Very few of us even know anyone who’s in it. There’s no shame in that. That we have sailed on a yacht of good fortune most of our lives — supportive generous families, a stable peaceful democracy, excellent schooling, prestigious careers and companies, relatively good health – is nothing to be ashamed of. Consider yourselves remarkably blessed.

What is shameful though, is that in a country with so many problems, with such a heaving underclass, we find the so-called ‘best and brightest,’ the 20-and 30-somethings who emerge from the top American graduate and undergraduate programs, abandoning their former hangout,Wall Street, to pile into anti-problem entrepreneurship.

Look, I worked for Goldman Sachs immediately after graduating from Wellesley. After graduating from MIT, I worked at a hedge fund. I am not throwing stones. Here in hell, the stones wouldn’t reach you anyhow… If you’re under 30 and in finance, you’ve definitely noticed the radical migration of your peers from Wall Street to Silicon Valley and Silicon Alley. This should have been a good exchange. When I first entered banking, leftist hippie that I was (and still am), my biggest issue was what struck me as a kind of gross intellectual malpractice: how could so many bright historians and economists, athletes and engineers, writers and biogeneticists, from every great school you could think of – Princeton, Berkeley, Oxford, Harvard, Imperial, Caltech, Amherst, Wharton, Yale, Swarthmore, Cambridge, and so on — be concentrated into a single sector, working obscene hours at a sweatshop to manufacture money?

When I look at the bulk of startups today – while there are notable exceptions (Code for America for example, which invites local governments to request technology help from teams of coders) – it doesn’t seem like we’ve aspired to something nobler: it just looks like we’ve shifted the malpractice from feeding the money machine to making inane, self-centric apps. Worse, is that the power players, institutional and individual — the highflying VCs, the entrepreneurship incubators, the top-ranked MBA programs, the accelerators, the universities, the business plan competitions have been complicit in this nonsense.

Those who are entrepreneurially-minded but young and idea-poor need serious direction from those who are rich in capital and connections. We see what ideas are getting funded, we see money flowing like the river Ganges towards insipid me-too products, so is it crazy that we’ve been thinking small? building smaller? that our “blood and judgment” to quote Hamlet, have not been “so well commingled?”

We need someone bold (and older than us) to stand up for Big Problems which are tough and dirty. But what we especially need is someone to stand up for big problems – little b, little p –which are tough and dirty and too easy to overlook.

We need:

A Ron Conway, a Fred Wilson-type at the venture level to say, ‘Kiddies, basta with this bull*%!.. This year we’re only investing in companies targeting the unexotic underclass.”

A Paul Graham and his Y Combinator at the incubator level, to devote one season to the underclass, be it veterans, single moms or overworked young doctors, Native Americans, the list is long: “Help these entrepreneurs build something that will help you.”

The head of an MIT or an HBS or a Stanford Law at the academic level, to tell the entire incoming class: “You are lucky to be some of the best engineering and business and law students, not just in the country, but in the world. And as an end-of-year project, you are going to use that talent to develop products, policy and programs to help lift the underclass.”

Of the political class, I ask nothing. With a vigor one would have thought inaccessible to people at such an age, our leaders in Washington have found ever innovative ways to avoid solving the problems that have been brought before them. Playing brinkmanship games with filibusters and fiscal cliffs; taking money to avoid taking votes. They are entrepreneurs of the highest order: presented with 1 problem, they manage to create 5 more. They have demonstrated that government is not only not the answer, it is the anti-answer…

The dysfunction in D.C. is a big problem.

Entrepreneurs: it looks like there’s work for you there too…

C.Z. Nnaemeka studied Philosophy at Wellesley; logically, she has spent most of her time in finance, beginning at Goldman Sachs. Born in Manhattan to Nigerian parents, she attended French schools, graduating from the Lycée Français de New York. Since then she has alternated between writing, banking, and consulting to startups in Europe, Latin America, and Australia. Previously, she lived in Paris where she founded a political discussion group and was a foreign affairs commentator for the conservative newspaper, Le Figaro. She graduated from MIT in 2010, focusing on Entrepreneurship + Innovation.

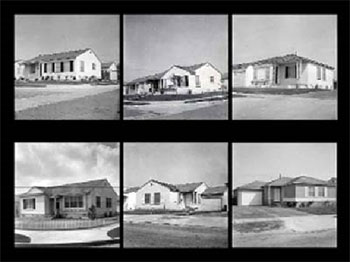

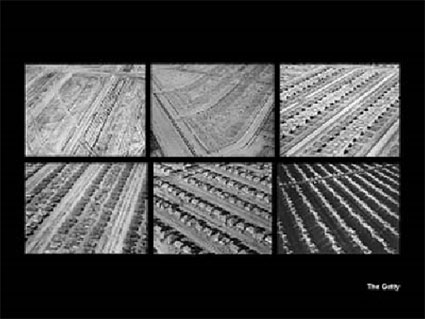

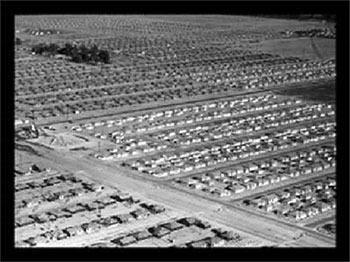

There is a persistent belief that suburban places like mine must be awful places they must be inhuman and soul-destroying places. That belief persists partly because of these photographs, taken by a brilliant young aerial photographer named William Garnett who worked for the developers of Lakewood between 1950 and 1952.

There is a persistent belief that suburban places like mine must be awful places they must be inhuman and soul-destroying places. That belief persists partly because of these photographs, taken by a brilliant young aerial photographer named William Garnett who worked for the developers of Lakewood between 1950 and 1952.

And we know that Boyer, Taper, and Weingart and Fritz Burns and Joseph Eichler and Henry Kaiser understood that the Progressive era model of low-cost housing they had adapted to mass production would result in new relationships to the idea of place. Garnett’s photographs of deeply shadowed forms on a titanic grid would for some critics and many Americans permanently define that relationship as dread.

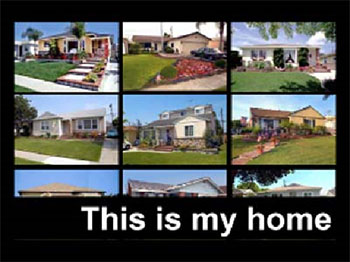

And we know that Boyer, Taper, and Weingart and Fritz Burns and Joseph Eichler and Henry Kaiser understood that the Progressive era model of low-cost housing they had adapted to mass production would result in new relationships to the idea of place. Garnett’s photographs of deeply shadowed forms on a titanic grid would for some critics and many Americans permanently define that relationship as dread. Despite everything that was mistaken or squandered in making my suburb, I believe a kind of dignity was gained. More men than just my father have said to me that living in my kind of place gave them a life made whole and habits that did not make them feel ashamed.

Despite everything that was mistaken or squandered in making my suburb, I believe a kind of dignity was gained. More men than just my father have said to me that living in my kind of place gave them a life made whole and habits that did not make them feel ashamed.

There are Californians who don’t regard a tract house as a place of pilgrimage, but my parents and their friends did. They were grateful for the comforts of their not-quite-middle-class life. Their aspiration wasn’t for more but only for enough despite the claims of critics then and now who assume that suburban places are about excess.

There are Californians who don’t regard a tract house as a place of pilgrimage, but my parents and their friends did. They were grateful for the comforts of their not-quite-middle-class life. Their aspiration wasn’t for more but only for enough despite the claims of critics then and now who assume that suburban places are about excess.