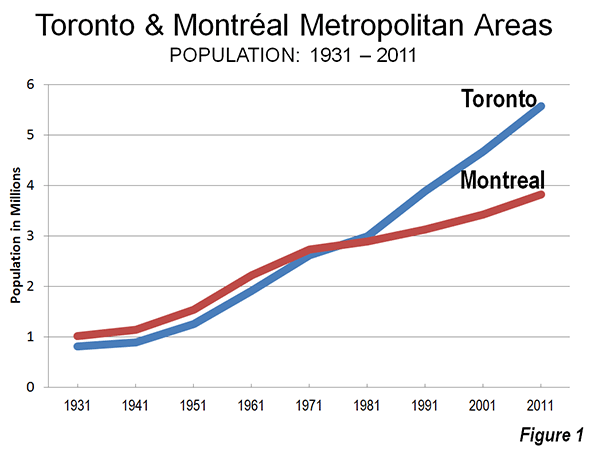

Toronto is the largest city (metropolitan area) in Canada and its principal commercial center. However, this is a relatively recent development. Toronto displaced Montréal is Canada’s largest city during the 1960s. Since the 1971 census, when the two Metropolitan areas were nearly identical size, Toronto has added approximately 3 million people, while Montréal has added approximately 1,000,000 (Figure 1).

This shift is exceptional within the high-income world over the past half century. Toronto’s ascendancy was in large part precipitated by the move by Québec, in which Montréal is the largest city, to assert the primacy of the French language even though much of the Montréal business community was Anglophone. Many of these businesses, and some of their employees, decamped to Toronto.

Metropolitan, Suburban and Core Population Growth: 1931-2011

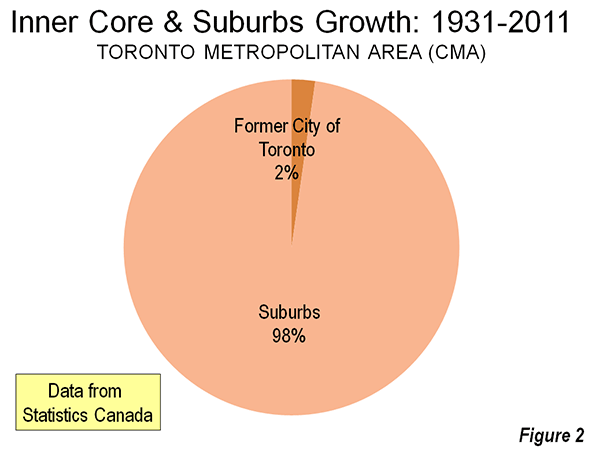

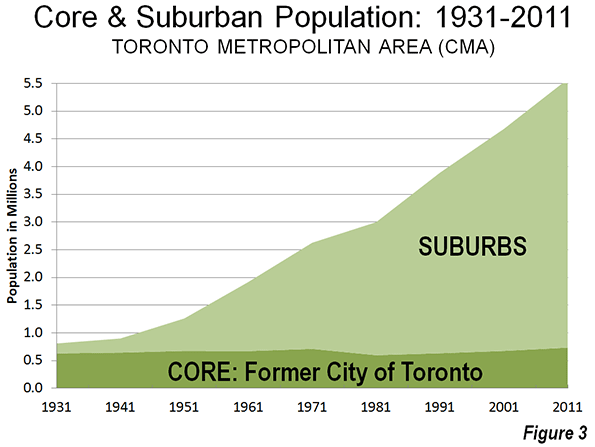

Toronto has grown very rapidly. In 1931, the metropolitan area had little more than 800,000 residents. About 80% of these (630,000) lived in the former city of Toronto. Since that time, nearly all of the growth in the Toronto metropolitan area has been in the suburbs (Figure 2). The area of the former city of Toronto (abolished in 1998 as a part of a six jurisdiction amalgamation, see Note on the Toronto Amalgamation) has added little more than 100,000 residents while the suburban areas have added approximately 4.7 million. By 2011, the metropolitan area had grown to a population of 5.5 million (Figure 3).

In recent decades, Toronto has been among the fastest-growing larger metropolitan areas in the high income world.

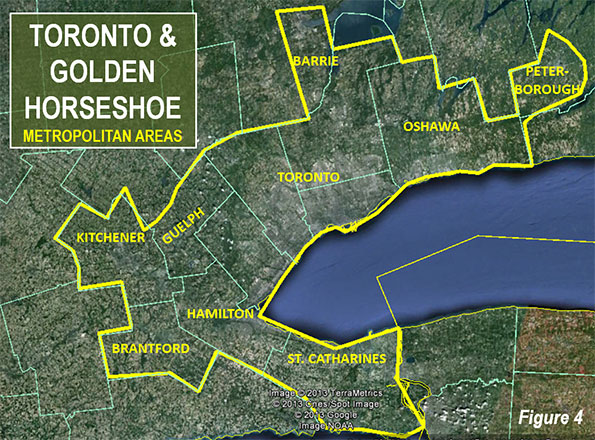

The Larger Region: The Golden Horseshoe

The Toronto metropolitan area is at the core of a much larger region of urbanization that is referred to as the Golden Horseshoe. The Golden Horseshoe stretches in the shape of a horseshoe from the US border at Niagara Falls (St. Catharine’s metropolitan area) through the Hamilton metropolitan area to Toronto and on to the Oshawa and Peterborough metropolitan areas to the east. The Golden Horseshoe (which can be defined in various ways), also includes the Kitchener, Brantford, Guelph, and Barrie metropolitan areas.

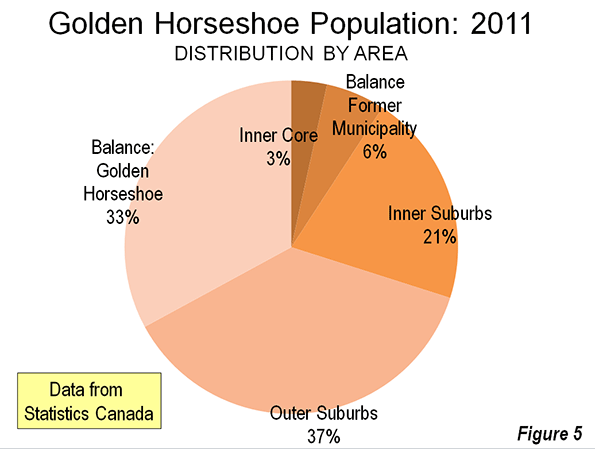

Overall the Golden Horseshoe registered a population of approximately 8.1 million in the 2011 census. Approximately 9% of the population lives in the former city of Toronto, 3% in the inner core federal electoral districts of Toronto – Centre and Trinity – Spadina and another 6% in the balance of the former city. Approximately 91% of the population is in the rest of the Golden Horseshoe (Figure 5).

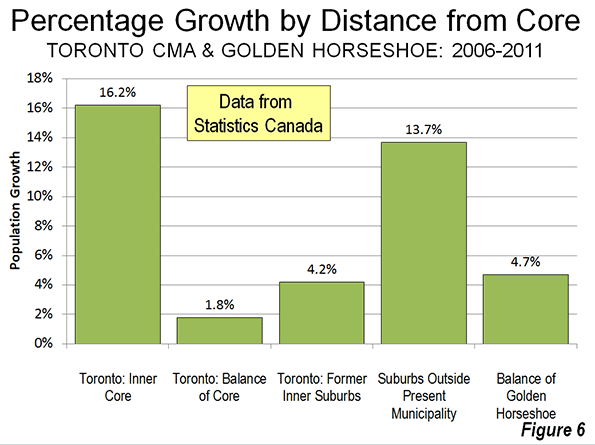

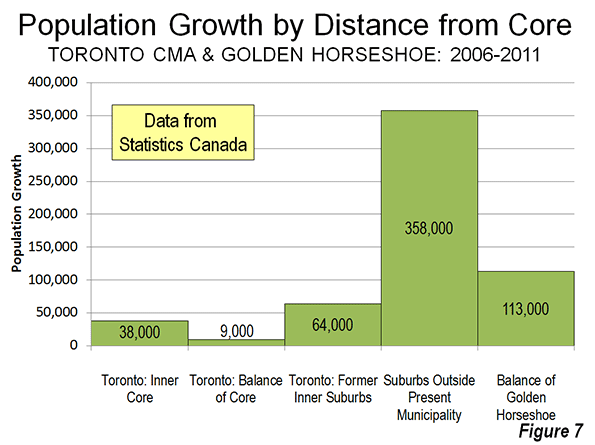

Like many other metropolitan areas, Toronto’s core has experienced a resurgence. Between 2006 and 2011, the inner core two districts added 16.2% to their population (Figure 6). This was a much stronger increase than occurred in the federal electoral districts that roughly correspond to the balance of the former city of Toronto, which grew 1.8%. The inner suburbs grew somewhat more strongly, at 4.2%. This rate of growth, barely one-quarter that of the inner core districts, was a more than 1.5 times the actual population increase of the inner core districts.

The outer suburbs within the metropolitan area grew 13.7%. While the outer suburban growth rate was less than that of the inner core districts, the actual population increase was more than nine times as great. The balance of the Golden Horseshoe grew 4.7%, slightly more than the inner suburbs.

Between 2006 and 2011 the overwhelming majority – 92 percent – of population growth was outside the core roughly corresponding to the former city of Toronto. This is less than the percentage of the total population represented by the inner core in the 2006 census. This is similar to the dynamics of metropolitan population growth in the United States, where inner core districts dominated central city growth, but produce little or none of the overall growth because of the stagnant or declining populations in the areas immediately outside the inner core.

The Urban Area

The Toronto urban area (called “population centre” by Statistics Canada) had a population of approximately 5.1 million according to the 2011 census. With a land area of 675 square miles (1,750 square kilometers), Toronto’s population density is 7,590 per square mile (2,930 per square kilometer). Toronto is the only major urban area in the New World (Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States) that is more dense than Los Angeles, which had 7,000 residents per square mile (2,700 per square kilometer), according to the 2010 census (Note on extended urban areas).

Canada’s Largest Employment Center

It is not surprising that Canada’s largest employment center should be in its largest metropolitan area. Surprisingly it is not downtown Toronto, but rather the Pearson International Airport area, which is shared between the municipalities of Mississauga, Brampton, and Toronto that is the top job center. This large area covers approximately 45 square miles (120 square kilometers), an area as large as either the municipalities of Vancouver or San Francisco. The center is largely made up of low rise transportation and distribution facilities that stretched far from the airport itself. Overall, the Pearson International Airport center has an employment level of more than 350,000.

In contrast downtown Toronto has approximately 325,000 jobs crammed into an area of 2.3 square miles (6 square kilometers). This highly concentrated area is, however, the focal point of transit’s largest commuting market in Canada.

The contrast between these two employment markets vividly illustrates the substantial strengths of transit in serving highly concentrated employment centers, like downtown Toronto, and its virtual inability to provide automobile competitive service in more highly dispersed employment centers (see Note on Transit and Employment Concentration)

Overall, only 13 percent of the employment in the metropolitan area (as opposed to the Golden Horseshoe) is in downtown Toronto.

As Goes Toronto, So Goes Canada

Toronto and the Golden Horseshoe are particularly important to Canada. The Golden Horseshoe has more than one quarter of Canada’s population. This is an unusually high proportion of a nation’s population for one highly urbanized region and boasts an even larger share of its economic output. By comparison, the largest metropolitan region in the United States, New York, represents barely 7% of the nation’s population. In many ways, Canada’s prosperity, which has been impressive in recent years, depends on the success of Toronto and the Golden Horseshoe.

See Also: A Toronto Condo Bubble?

————–

Note on the Toronto Amalgamation: The former city of Toronto and five other municipal jurisdictions were amalgamated under an act of the Ontario government in 1998. The amalgamation was promoted by the government on efficiency grounds, claiming that hundreds of millions annually would be saved. I was hired by the former city to assist it in an effort to defeat the amalgamation proposal. Our side argued that the cost savings would not occur because of the necessity of harmonizing (the leveling up) labor costs and service levels. Despite advisory referendums that receive a minimum of a 70% no vote, the amalgamation went forward.

The amalgamation is still a controversial subject. The financial argument appears to have been resolved in the favor of the position of the former city. A major Toronto business organization, the Toronto City Summit Alliance reported “The amalgamation of the City of Toronto has not produced the overall cost savings that were projected. Although there have been savings from staff reductions, the harmonization of wages and service levels has resulted in higher costs for the new City. We will all continue to feel these higher costs in the future.” My commentary in the National Post on the tenth anniversary of the amalgamation summarized the experience.

In a spirited debate in 2001 at Ryerson University, in downtown Toronto with a former Toronto transit commission official, my opponent and I agreed on one issue, that the amalgamation of Toronto had been a mistake.

Note on Extended Urban Areas: In fact, the continuous urbanization of Toronto extends further, to the west into the Hamilton metropolitan area and to the east into the Oshawa metropolitan area. If these areas are combined into a single urban area, the population density falls to 7000 per square mile (2,700 per square kilometer). Even with this extension, Toronto would be more dense than an extended Los Angeles urban area (extending to include Mission Viejo and the western Inland Empire, at 6,200 per square mile or 2,400 per square kilometer (These larger urban area definitions are used in Demographia World Urban Areas)).

Note on Transit and Employment Concentration: It is virtually impossible for employees throughout the metropolitan area to reach the airport area on transit that is time-competitive with the automobile. This disadvantage is not easily solved. If grade-separated rapid transit lines (such as a subway or busway) were built to the area, only a small percentage of the jobs would be within walking distance (within one quarter mile or 400 metres). Walks of up to 5 miles (8 kilometers) could be necessary from stations to employment locations. This compares with the virtually 100 per cent of downtown jobs that are accessible by walking from subway and commuter rail (Go Transit) stations (See Improving the Competitiveness of Metropolitan Areas)

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

Photograph: Google Earth Image of the Pearson Airport employment area (Canada’s largest employment area)