America’s urban landscape is changing, but in ways not always predicted or much admired by our media, planners, and pundits. The real trend-setters of the future—judged by both population and job growth—are not in the oft-praised great “legacy” cities like New York, Chicago, or San Francisco, but a crop of newer, more sprawling urban regions primarily located in the Sun Belt and, surprisingly, the resurgent Great Plains.

While Gotham and the Windy City have experienced modest growth and significant net domestic out-migration, burgeoning if often disdained urban regions such as Houston, Dallas-Ft. Worth, Charlotte, and Oklahoma City have expanded rapidly. These low-density, car-dominated, heavily suburbanized areas with small central cores likely represent the next wave of great American cities.

There’s a whole industry led by the likes of Harvard’s Ed Glaeser, my occasional sparring partner Richard Florida and developer-funded groups like CEOs for Cities, who advocate for old-style, high-density cities, and insist that they represent the inevitable future.

But the numbers tell a different story: the most rapid urban growth is occurring outside of the great, dense, highly developed and vastly expensive old American metropolises.

An aspirational city, by definition, is one that people and industries migrate to improve their economic prospects and achieve a better relative quality of life. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, this aspirational spirit was epitomized by cities such as New York and Chicago and then in the decades after World War Two by Los Angeles, which for many years was the fastest-growing big city in the high-income world.

Until the 1970s, the country’s established big cities were synonymous with aspiration—where the jobs and opportunities for broad portions of the population abounded. But as the financial markets took on an oversized role in the American economy and manufacturing receded, the cost of living in the nation’s oldest metropolises shot up far faster than the median income there—and Americans have turned elsewhere now that, as Virginia Postrel wrote in an important essay on the nation’s growing economic wall, “the promise of a better life that once drew people of all backgrounds to rich places like New York and [coastal] California now applies only to an educated elite—because rich places have made housing prohibitively expensive.”

Like the great legacy cities during their now long-past adolescent and at times ungainly growth spurts, today’s aspirational cities often meet with little approval from travelers from other, older cities. A 19th-century Swedish visitor to Chicago described it as “one of the most miserable and ugly cities” in North America. New York, complained the French Consul in 1810, was a city where the inhabitants had “in general no mind for anything but business”; later Bostonian Ralph Waldo Emerson, granted Gotham’s entrepreneurial supremacy only to explain that his more cultured “little city” was “appointed” by destiny to “lead the civilization of North America.”

Los Angeles, most of whose early-20th-century migrants came from the Midwest, became a favorite object of scorn from sophisticates. William Faulkner in the 1930s described the city of angels as “the plastic asshole of the world.” As the first great city built largely around the automobile, mainstream urbanists detested it; their icon Jane Jacobs called it “a vast blind-eyed reservation.”

A half century later, today’s aspirational urban centers suffer similarly poor reputations among urbanists, planners and journalists. One New York Post reporter recently described Houston as “brutally ugly” while new urbanists like Andres Duany relegate the region to a netherworld inhabited by car-centric cities such as Phoenix and Atlanta.

Yet over the past decade the 25 fastest-growing cities have been mostly such urbanist “assholes”—Raleigh, Austin, Houston, San Antonio, Las Vegas, Orlando, Dallas-Fort Worth, Charlotte, and Phoenix. Despite hopeful claims from density advocates that the Great Recession and the housing bust ended this trend, the latest census data shows that Americans have continued choosing places that are affordable enough to offer opportunity, and space.

One common article of faith among mainstream urbanists, at least when they stop to note this growth at all, is that these cities grow mainly because they are cheap and can house the unskilled. But in reality many of these metropolitan areas are also leading the nation in growing their number of well-educated arrivals. Houston, Charlotte, Raleigh, Las Vegas, Nashville, and San Antonio, for example, experienced increases in the number of college-educated residents of nearly 40 percent or more over the decade, roughly twice the level of growth as in “brain centers” such as Boston, San Francisco, San Jose (Silicon Valley), or Chicago. Atlanta, Houston, and Dallas each have added about 300,000 college grads in the past decade, more than greater Boston’s pickup of 240,000 or San Francisco’s 211,000.

Once considered backwaters, these Sunbelt cities are quietly achieving a critical mass of well-educated residents. They are also becoming major magnets for immigrants. Over the past decade, the largest percentage growth in foreign-born population has occurred in sunbelt cities, led by Nashville, which has doubled its number of immigrants, as have Charlotte and Raleigh. During the first decade of the 21st century, Houston attracted the second-most new, foreign-born residents, some 400,000, of any American city—behind only much larger New York and slightly ahead of Dallas-Ft. Worth, but more than three times as many as Los Angeles. According to one recent Rice University study, Census data now shows that Houston has now surpassed New York as the country’s most racially and ethnically diverse metropolis.

Why are these people flocking to the aspirational cities, that lack the hip amenities, tourist draws, and cultural landmarks of the biggest American cities? People are still far more likely to buy a million dollar pied à terre in Manhattan than to do so in Oklahoma City. Like early-20th-century Polish peasants who came to work in Chicago’s factories or Russian immigrants, like my grandparents, who came to New York to labor in the rag trade, the appeal of today’s smaller cities is largely economic. The foreign born, along with generally younger educated workers, are canaries in the coal mine—singing loudest and most frequently in places that offer both employment and opportunities for upward mobility and a better life.

Over the decade, for example, Austin’s job base grew 28 percent, Raleigh’s by 21 percent, Houston by 20 percent, while Nashville, Atlanta, San Antonio, and Dallas-Ft. Worth saw job growth in the 14 percent range or better. In contrast, among all the legacy cities, only Seattle and Washington D.C.—the great economic parasite—have created jobs faster than the national average of roughly 5 percent. Most did far worse, with New York and Boston 20 percent below the norm; big urban regions including Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and, despite the current tech bubble, San Francisco have created essentially zero new jobs over the decade.

Another common urban legend maintains these areas lag in terms of higher-wage employment, lacking the density essential for what boosters like Glaeser and Florida describe as “knowledge-intensive cities.” Defenders of traditional cities often cite Santa Fe Institute research that they say links innovation with density—but actually does nothing of the kind. Rather, that research suggests that size, not compactness, constitutes the decisive factor. After all, it’s hard to define Silicon Valley, still the nation’s premier innovation region, as anything other than large, sprawling, and overwhelmingly suburban in form.

Size does matter and many of the fastest growth areas are themselves large enough to sport a major airport, large corporate presences and other critical pieces of economic infrastructure. The largest gains in GDP (PDF) in 2011 were in Houston, Dallas and, surprisingly, resurgent greater Detroit (and that despite its shrinking urban core). None of these areas are characterized by high density yet their income growth was well ahead of Seattle, San Francisco, or Boston, and more than twice that of New York, Washington, or Chicago.

But in fact neither density nor size necessarily determine which regions generate new high-end jobs. The growth in STEM—or science-technology-engineering and mathematics-related—employment in Houston, Raleigh, Nashville, Austin, and Las Vegas surpassed that in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Boston, or New York. One reason: most STEM jobs are not found in fashionable fields like designing social media or videogames but in more prosaic activities tied to medicine, manufacturing, agriculture and (horror of horrors) natural resource extraction, including fossil fuel energy. In this sense, technology reflects the definition of the French sociologists Marcel Mauss as “a traditional action made effective.”

This pattern also extends to growth in business and professional services, the nation’s biggest high-wage job category. Since 2000, Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, Charlotte, Austin and Raleigh expanded their number of such jobs by twenty percent or more—twice the rate as greater New York, the longtime business-service capital, while Chicago and San Jose actually lost jobs in this critical category.

Finally there is the too often neglected topic of real purchasing power—that a dollar in New York doesn’t go nearly as far as one in Atlanta, for example. My colleague Mark Schill at the Praxis Strategy group has calculated the average regional paycheck, adjusted for cost of living. Houston led the pack in real median pay in, and seven of the 10 cities with the highest adjusted salary were aspirational ones (the exceptions were San Jose-Silicon Valley, Seattle, and the greater Detroit region). Portland, Los Angeles, New York, and San Diego all landed near the bottom of the list.

Conventional urbanists—call them density nostalgists—continue to see the future in legacy cities that, as the University of Washington demographer Richard Morrill notes, were built out before the dominance of the car, air-conditioning and with them the prevalence of suburban lifestyles.

Looking forward, it is simply presumptuous and ahistorical to dismiss the fast-growing regions as anti-cities, as 60s-era urbanists did with places like Los Angeles. When tradition-bound urbanists hope these sprawling young cities choke on their traffic and exhaust fumes, or from rising energy costs, they are reflecting the classic prejudice of city-dwellers of established urban centers toward upstarts.

The reality is that most urban growth in our most dynamic, fastest-growing regions has included strong expansion of the suburban and even exurban fringe, along with a limited resurgence in their historically small inner cores. Economic growth, it turns out, allows for young hipsters to find amenable places before they enter their 30s, and affordable, more suburban environments nearby to start families.

This urbanizing process is shaped, in many ways, by the late development of these regions. In most aspirational cities, close-in neighborhoods often are dominated by single-family houses; it’s a mere 10 or 15 minute drive from nice, leafy streets in Ft. Worth, Charlotte, or Austin to the urban core. In these cities, families or individuals who want to live near the center can do without being forced to live in a tiny apartment.

And in many of these places, the historic underdevelopment in the central district, coupled with job growth, presents developers with economically viable options for higher-density housing as well. Houston presents the strongest example of this trend. Although nearly 60 percent of Houston’s growth over the decade has been more than 20 miles outside the core, the inner ring area encompassed within the loop around Interstate 610 has also been growing steadily, albeit at a markedly slower rate. This contrasts with many urban regions, where close-in areas just beyond downtowns have been actually losing population.

Even as Houston has continued to advance outwards, the region has added more multiunit housing over the past decade than more populous New York, Los Angeles or Chicago. With its economy growing faster and producing wealth faster than any other region in the country, urban developers there usually do not need subsidies or planning dictates to be economically viable.

Modern urban culture also is spreading in the Bayou City. In what has to be a first, my colleagues at Forbes recently ranked Houston as America’s “coolest city,” citing not only its economy, but its thriving arts scene and excellent restaurants. Such praise may make some of us, who relish Houston’s unpretentious nature, a little nervous—but it shows that hip urbanism can co-exist with rapidly expanding suburban development.

And Houston’s not the only proverbial urban ugly duckling having an amenity makeover. Oklahoma City has developed its central “Bricktown” into a centerpiece for arts and entertainment. Ft. Worth boasts its own, cowboy-themed downtown, along with fine museums, while its rival Dallas, in typical Texan fashion, boasts of having the nation’s largest arts district.

More important still, both for families and outdoor-oriented singles, both cities are developing large urban park systems. At an expense of $30 million, Raleigh is nearing the completion of its Neuse River Greenway Trail, a 28-mile trail through the forested areas of Raleigh. Houston has plans for a series of bayou-oriented green ways. For its part, Dallas is envisioning a vast new 6,000 acre park system, along the Trinity River that will dwarf New York’s 840-acre Central Park.

To be sure, there’s no foreseeable circumstance in which these cities will challenge Paris or Buenos Aires, New York, or San Francisco as favored destinations for those primarily motivated by aesthetics that are largely the result of history. Nor are they likely to become models of progressive governance, as poverty and gaps in medical coverage become even more difficult problems for elected officials without a well-entrenched ultra-wealthy class to cull resources from.

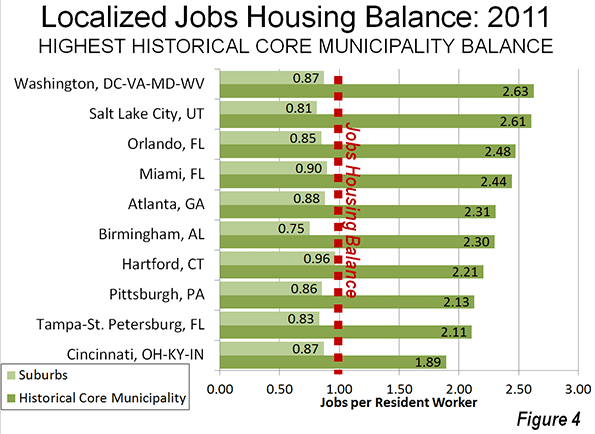

Finally, they will not become highly dense, apartment cities — as developers and planners insist they “should.” Instead the aspirational regions are likely to remain dominated by a suburbanized form characterized by car dependency, dispersion of job centers, and single-family homes. In 2011, for example, twice as many single-family homes sold in Raleigh as condos and townhouses combined. The ratio of new suburban to new urban housing, according to the American Community Survey, is 10 to 1 in Las Vegas and Orlando, 5 to 1 in Dallas, 4 to 1 in Houston and 3 to 1 in Phoenix.

Pressed by local developers and planners, some aspirational cities spend heavily on urban transit, including light rail. To my mind, these efforts are largely quixotic, with transit accounting for five percent or less of all commuters in most systems. The Charlotte Area Transit System represents less a viable means of commuting for most residents than what could be called Manhattan infrastructure envy. Even urban-planning model Portland, now with five radial light rail lines and a population now growing largely at its fringes, carries a smaller portion of commuters on transit than before opening its first line in 1986.

But such pretentions, however ill-suited, have always been commonplace for ambitious and ascending cities, and are hardly a reason to discount their prospects. Urbanistas need to wake up, start recognizing what the future is really looking like and search for ways to make it work better. Under almost any imaginable scenario, we are unlikely to see the creation of regions with anything like the dynamic inner cores of successful legacy cities such as New York, Boston, Chicago or San Francisco. For better or worse, demographic and economic trends suggest our urban destiny lies increasingly with the likes of Houston, Charlotte, Dallas-Ft. Worth, Raleigh and even Phoenix.

The critical reason for this is likely to be missed by those who worship at the altar of density and contemporary planning dogma. These cities grow primarily because they do what cities were designed to do in the first place: help their residents achieve their aspirations—and that’s why they keep getting bigger and more consequential, in spite of the planners who keep ignoring or deploring their ascendance.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

This piece originally appeared in the The Daily Beast.

Photo by telwink.