Recently the Detroit Works Project released their long awaited strategic plan for the city. This is the one led by Toni Griffin that produced a lot of public controversy because of suggestions it would result in the planned shrinkage or decommissioning (or even forced residential relocations) in sparsely populated neighborhoods.

Called “Detroit Future City,” this plan doesn’t shy away from facing the tough realities that face Detroit, but its recommendations are somewhat muted with regards to shrinkage. Nevertheless, the message is clear: in a broke, declining city, neighborhood triage is a must.

The full document is 184 pages. I perused it, but wasn’t able to review at the level of detail I normally like to. Partially this is because it was published in a hyper-annoying “cinemascope” type format that makes it almost impossible to read on screen without magnification and lots of horizontal scrolling. This aspect of the plan’s publication was an immediate knock against it in my view. However, it will share a few observations I gleaned.

Neighborhood Development

The plan is notable for admitting that Detroit can never be repopulated. In fact, its only goal is to stabilize population loss 20 years from now, and settle in for a population of 600-800,000 people, or approximately the same as now.

The plan is frank about the scale of the challenges, including 150,000 vacant and abandoned parcels, empty land equal to the area of Manhattan, and vastly oversized infrastructure relative to the population and industrial base, along with poor service delivery in areas ranging from public safety (Detroit has the second highest violent crime rate in the country) to street lighting (about half of the street lights don’t work).

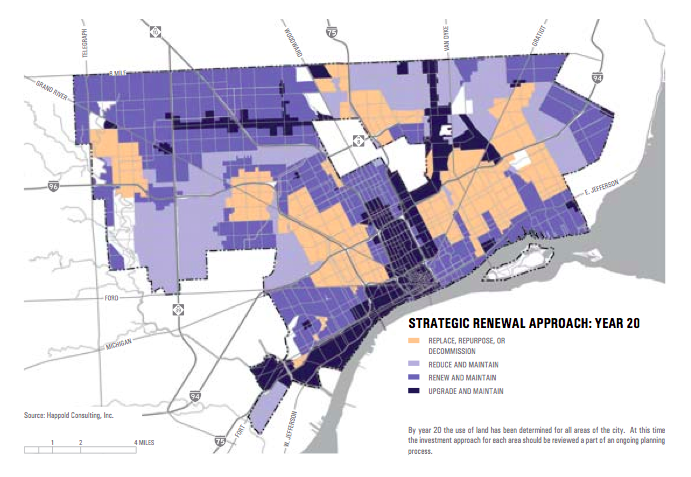

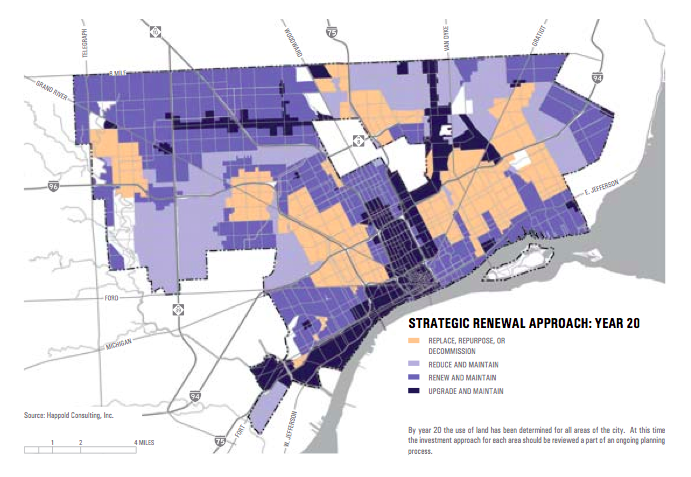

Part of that does involve identifying how to deploy infrastructure in neighborhoods. Here’s a graphic on that which will no doubt get some airplay:

Some areas are slated for upgrades, others reductions, and some perhaps “decommissioning.”

The strength of the plan, however, is in its approach to development in which the core concept is to develop a multi-nodal network of neighborhoods, and to have neighborhoods that are strategically differentiated from each others. This is very different from the core-centric or “hub and spoke” model that exists today, and is somewhat similar to my “100 Monument Cirles” concept for Indianapolis. Suffice it to say, I like it. What was missing from this was strengthening neighborhood identify, something Pete Saunders identified as a key weakness of the city.

A lot of the content behind this is disappointingly standard, however. The focus is green infrastructures, transit, mixed use neighborhoods, etc. This is basically planning conventional wisdom that would be at home in lots of different cities.

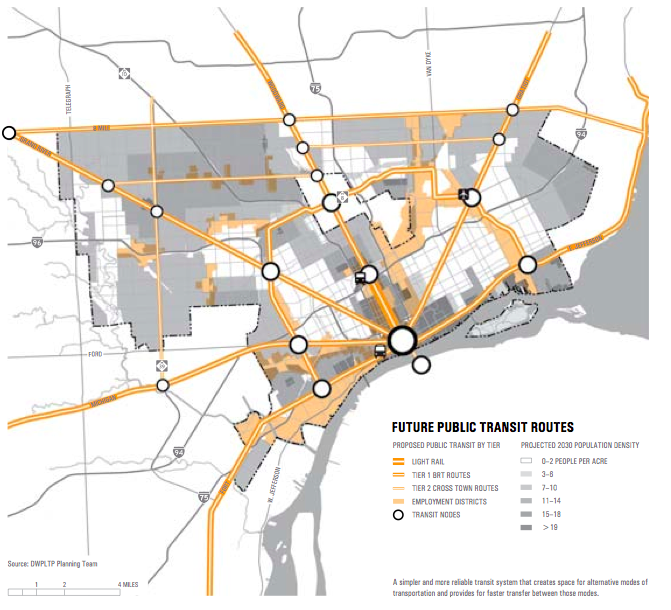

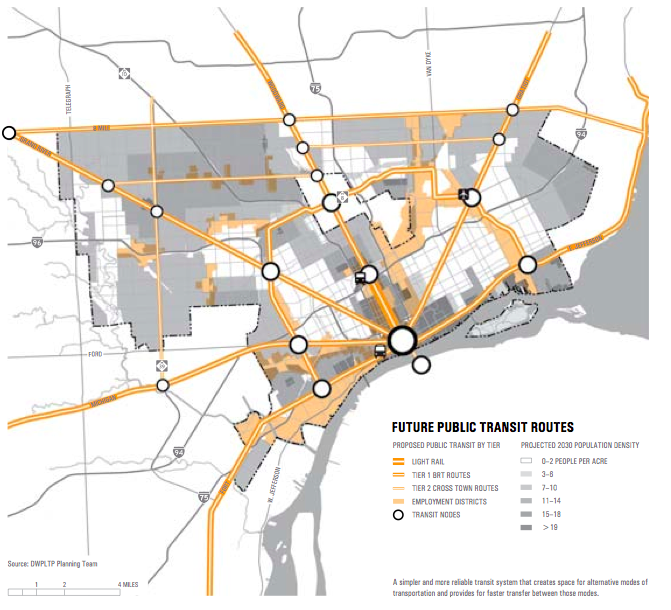

I was pleased to see that they de-emphasized rail transit. Only the M-1 light rail on Woodward remains. The rest of the core network would be BRT. I’d argue that reliable and higher frequency “plain old bus service” is the core need, however. There’s the proposed transit map:

Some may decry this, but in a city that’s over-infrastructured as it is, the last thing you need is more physical plant to maintain over time.

And perhaps the focus on green is to some extent understandable given the vast quantity of vacant land in Detroit. One of their intriguing concepts is “landscape as infrastructure”, though it didn’t fully connect with me. They did talk about ideas like medium intensity agriculture and new urban forest typologies. The Hanzt Farm example shows this already underway.

Lastly, the focus, and especially the near term recommendations around, regulatory restructuring is critical. Detroit benefits today from a sort of laissez-faire environment because government is so ineffective. If government effectiveness were restored, it could easily strangle the good things happening in Detroit, which are largely non-conforming. The answer is to get the regulatory system up to date with what we want to see. I would have preferred to see some types of harder targets around this, such as “85% of new development approved as of right.”

Economic Development

The plan considers boosting the number of jobs in Detroit as the most important mission. The city today has the 5th lowest number of jobs per resident of any of the top 100 cities in America, this despite large population losses. Jobs in the city are needed both for residents and rebuild the tax base.

The numbers on this seemed a bit squishy though. The report says that there is one job for ever four residents of Detroit. As there are about 700,000 residents, this would mean about 175,000 jobs. Yet they say there are 350,000 jobs. (If the resident figure included only working age adults, the projected number of current jobs would be even lower than my estimate).

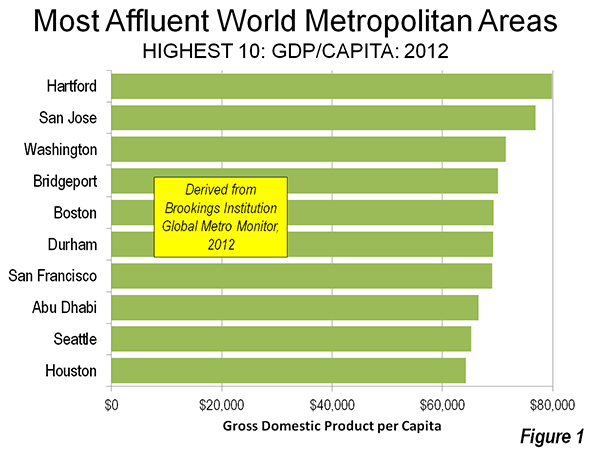

The goal by 2030 is to increase this to between 2 and 3 jobs for every resident. This implies simply staggering job growth. Their mid-point population estimate for 2030 is still 700,000, so to go from 0.25/1 to 2/1 or 3/1 implies 700-1100% job growth. This is a CAGR of 11-13% – off the charts. To put it in perspective, metro Houston’s job growth CAGR from 2000 to 2011 was only 1.3%.

I may be totally off base on what they were getting at in these numbers, but having solid and realistic projections is critical, and, alas, all too rare. Unrealistic growth rate assumptions are common in civic plans, as I highlighted in the example of Cincinnati’s Agenda 360 plan.

[ Update: I was contacted by someone from the study’s technical committee indicating that the 2 or 3 jobs per resident figure was an error in the PDF that was not present in the official version of the plan. There are apparently about 193,000 jobs in the city, with the plans actual goal a doubling of that over 30 years. Still ambitious, but not mathematically impossible. ]

The job growth is projected to come from four key target sectors: eds and meds, digital and creative, industrial, and local entrepreneurship. These sectors are reasonable as these things go given where Detroit is, but seem unlikely to drive the major growth they seek, excepting possibly entrepreneurship.

Neither Wayne State nor Detroit’s health care/life science infrastructure is nation leading. Every city and state in America is chasing eds and meds, and as I noted, the great growth curve in these industries may be over. Additionally, the trend nationally seems to be towards more decentralization of health care infrastructure in metro areas. While I’m sure there will be some growth here, I’m not optimistic about major expansion.

Similarly, digital and creative jobs are the fad du jour. I strongly doubt anyone will even consider there to be categories of jobs called “digital” or “creative” by 2030. These will be absorbed into industry generally. These are also the same types of sectors being pursued everywhere. Detroit certainly has a concentration of these because of its auto design cluster and just simply being a big city. But other than autos, does it really have a competitive advantage here? The big expansion opportunity would seem to be mostly suburban relocations of the type spearheaded by Dan Gilbert. I wonder how much gas is left in that tank, however.

The other two are more promising. Local entrepreneurship is a catch-all, but clearly indigenous startups are a great way to boost the economy. The report’s focus on equipping and facilitating minority entrepreneurship was especially relevant. Given the collapse of the city, Detroit’s residents have had to become innovative and self-sufficient of necessity. These skills from the school of hard knocks are in many ways worth much more than formal education when it comes to starting a business. If the city can figure out how to marry these “survival skills” of residents with a commercial orientation, it could be powerful. The same recipe of figuring how to do business in unstable and tough environments is common in the Middle East, where there’s a longstanding entrepreneurial and trading tradition. Unsurprisingly, Middle Easterners have been prominent among those who’ve thrived in Detroit. The challenge is how to activate the similar skills in other ethnicities for business purposes.

Industrial employment would also seem to be a possible area of growth, but not in the way envisioned in this plan. Industrial employment has been in decline, and new industrial facilities have tended to locate in outlying areas, not traditional urban manufacturing zones.

However, there are types of industrial businesses that can have a hard time finding a home. For places that are willing to welcome them, there could be opportunity. I noted this around the heavy industrial zone in Northwest Indiana.

This involves being willing to take on more brown than green industry, however. And it raises a whole host of issues around environmental justice, etc. However, Detroit, as this plan notes, is desperate for jobs. Trade-offs at least need to be considered. Rather than “focusing on the look and feel” of industrial areas, as the plan put it, why not roll out the red carpet for businesses like tanneries, scrap metal processing, etc. that are increasingly unwelcome in places like Chicago? Being friendly to to these types of businesses is probably the most likely road to success in industrial employment.

Conclusion

On first read, there’s some interesting stuff in here. They plan is less creative than I’d hoped overall, but probably takes the most aggressive line that was politically realistic. The real questions is, what happens next? Can any of this actually be actioned, or will fiscal and other problems effectively render it a dead letter? Only time will tell.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the founder of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile, where this piece originally appeared.