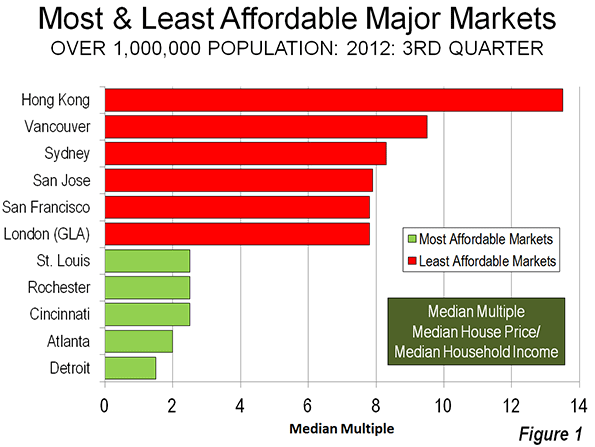

The just released 9th Annual Demographia Housing Affordability Survey (pdf) indicates that housing affordability has deteriorated modestly in the last year. A number of major metropolitan areas remain severely unaffordable.

Highlights: Metropolitan Areas

Among the 337 Metropolitan markets analyzed, Hong Kong remained the most unaffordable, with a median multiple (median house price divided by pre-tax median household income) of 13.5, up nearly a full point from last year’s 12.6. No other housing market has ever reached such an intense level of unaffordability since the Survey began (Los Angeles reached 11.5 in 2007).

Rounding out the least affordable major markets (over 1,000,000 population) were Vancouver at 9.5, Sydney at 8.3, San Jose (US) at 7.9, and a tie in fifth place between San Francisco and London (Greater London Authority) at 7.8. The most affordable markets were Detroit at 1.5 (Note 1); Atlanta, at 2.0 (Note 2); and Cincinnati, Rochester (US), and St. Louis at 2.5 (Figure 1).

Rating Housing Affordability

The Demographia Housing Affordability Surveydefines four housing affordability categories (Table 1), starting with "affordable." Affordable housing markets have a median multiple of 3.0 or less, the upper bound of overall housing affordability that existed virtually across all major markets in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Ireland and New Zealand before the adoption of urban containment policy (also called densification policy, urban consolidation, compact cities, smart growth, or growth management).

|

Table 1 Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey Housing Affordability Rating Categories |

|

|

Rating |

Median Multiple |

|

Severely Unaffordable |

5.1 & Over |

|

Seriously Unaffordable |

4.1 to 5.0 |

|

Moderately Unaffordable |

3.1 to 4.0 |

|

Affordable |

3.0 & Under |

Highlights: Nations

Of all nations, only the United States has affordable major markets and a strong representation in the moderately unaffordable category. Six major markets in the United States were rated in the severely unaffordable category, including San Jose, San Francisco, San Diego, Los Angeles and New York.

Canada had two markets rated moderately unaffordable, while one half of its major markets were rated severely unaffordable, including Vancouver, Toronto and Montréal. Ireland’s one major market, Dublin, was rated moderately unaffordable.

One half of the major markets in the United Kingdom were also rated severely unaffordable, including London (GLA), Plymouth & Devon, the London Exurbs (Southeast and East of England), Bristol, Liverpool, Newcastle, Birmingham, and Sheffield. All of the major markets in Australia (Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide), China (Hong Kong), and New Zealand (Auckland) were rated severely unaffordable (Table 2).

Hong Kong and Singapore are the world’s largest city-states. An analysis of a large share of the Singapore market suggests a median multiple of approximately 6.0, which is substantially more affordable than Hong Kong.

|

Table 2 Housing Affordability Ratings by Nation: Major Markets (Over 1,000,000 Population) |

||||||

|

Nation |

Affordable (3.0 & Under) |

Moderately Unaffordable (3.1-4.0) |

Seriously Unaffordable (4.1-5.0) |

Severely Unaffordable (5.1 & Over) |

Total |

Median Multiple |

|

Australia |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

6.5 |

|

Canada |

0 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

6 |

4.7 |

|

China (Hong Kong) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

13.5 |

|

Ireland |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3.6 |

|

New Zealand |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

6.7 |

|

United Kingdom |

0 |

0 |

8 |

8 |

16 |

5.1 |

|

United States |

20 |

20 |

5 |

6 |

51 |

3.2 |

|

TOTAL |

20 |

23 |

14 |

24 |

81 |

|

Longer Term Trends

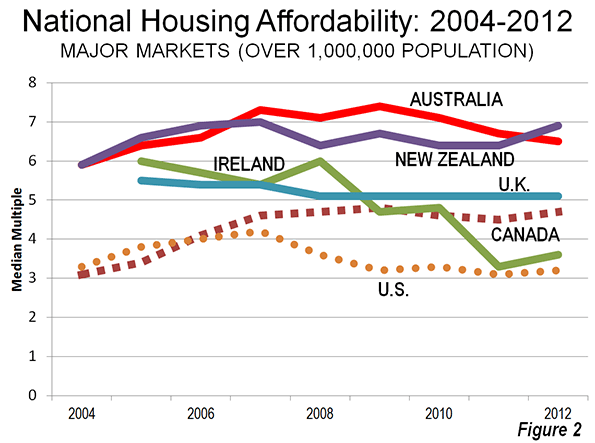

Over the years of the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey, housing affordability has improved by far the most in Ireland. It has also improved in the United States. Affordability in Canada’s major markets was the most favorable in 2004, but has seen large Median Multiple increases in each of the three largest metropolitan areas. As a result, there is increasing concern about housing affordability in Canada.

Australia and New Zealand have had the most unaffordable major markets, with every market being severely unaffordable in every year, reflecting earlier adoption of densification policy by states and metropolitan areas. Housing affordability has also been severely unaffordable in United Kingdom major markets over the period covered (Figure 2).

A Competitive Land Supply: Key to Housing Affordability

Overwhelming economic evidence indicates that urban containment policies, especially urban growth boundaries raise the price of housing relative to income. This inevitably leads to a reduced standard of living and increases poverty rates, because the unnecessarily higher costs of housing leave households with less discretionary income to spend on other goods and services. The higher costs ripple into rental markets, tightening the budgets of lower income households, who already suffer from lower discretionary incomes.

The principal driver of unaffordable housing relative to median incomes is failure to maintain a "competitive land supply." Brookings Institution economist Anthony Downs describes the process, noting that more urban growth boundaries can convey monopolistic pricing power on sellers of land if sufficient supply is not available, which, all things being equal, is likely to raise the price of land and housing that is built on it. This has, more often than not, been associated with urban containment policy and virtually never with the more liberal land use policy that preceded it.

Recent Policy Developments

The last year has seen public policy progress. The New Zealand central government plans to expand the land supply and provide alternatives for infrastructure finance, both of which are likely to lead to improved housing affordability. In his Introduction to this years’ Survey, Hon. Bill English, Deputy Prime Minister of New Zealand pinpoints the factors leading to the policy changes:

It costs too much and takes too long to build a house in New Zealand. Land has been made artificially scarce by regulation that locks up land for development. This regulation has made land supply unresponsive to demand. When demand shocks occur, as they did in the mid-2000s in New Zealand and around the world, much of that shock translates to higher prices rather than more houses.

The Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition is proposing policies to build housing on more competitively priced land, to improve housing affordability. Planning Minister Nick Boles has called Britain’s lack of housing affordability "the biggest social justice crisis we have," and called it bigger than education and unemployment (video). These proposals have been long in coming. It has been four decades since Sir Peter Hall and associates documented the consequences of urban containment, and nearly a decade since the similar conclusions of Kate Barker for the Labour Government.

In Hong Kong, facing public demonstrations on issues such as housing affordability, the government has adopted a plan to improve housing affordability.

However, the policy is deteriorating in California, where state regulations could virtually outlaw new single-family housing on the urban fringe. In the last year housing affordability losses have been substantial and could portend another housing bubble in this state that precipitated Great Financial Crisis with its egregious house price increases.

Evolving Perspectives

Planning perspectives could be evolving. New York University Professor Shlomo Angel writes in his book Planet of Cities of the importance of housing affordability and argues against urban planning restrictions that restricting adequate housing to ordinary households.

A team of UK academic researchers questioned the "default" preference for urban containment policy. This is an important development, since much of urban planning is committed to outlawing more liberal land-use policies.

The Economic Challenge

Nations around the world face serious economic challenges. Governments have taken on unaffordable obligations, and repayment continues to elude authorities in the United States, the European Union, and elsewhere. Future demographic trends are likely to only exacerbate this difficulty, driven by plummeting birth rates and a rising elderly population (See The Rise of Post-Familialism: Humanity’s Future?).

Urban policy needs a "reset." The emphasis should be shifted away from "designing" urban areas toward facilitating a better standard of living for the people who live in them. In his epic Civilization: The West and the Rest, historian Niall Ferguson, in his Civilization notes that

The success of the civilization is measured not just in its aesthetic achievements but also, and surely more importantly in the duration and quality of life of its citizens.

This requires greater affluence and less poverty, both of which require more affordable housing.

—–

Note 1: The city of Detroit has experienced a severe economic decline. However, the Detroit metropolitan area (which includes the city, the suburbs and exurbs) has fared much better. The city (municipality or local government authority of Detroit experienced a population loss from 1,850,000 to 714,000 in the last 60 years, while suburban and exurban areas added 2.2 million. There are a variety of theories about Detroit’s municipal decline, involving both "push" and "pull" factors (such as the incompetence and corruption of the municipal government to the not unrelated attraction of suburban living). Further, the overall population growth rate of the Detroit metropolitan area has not been strong, but exceeded that of the other three worst hit "Rust Belt metropolitan areas, Cleveland, Buffalo and Pittsburgh (which lost population). Metropolitan Detroit’s growth rate was similar to that of the New York metropolitan area (35 percent compared to 42 percent), which ranked 46th in growth (out of 51) compared to Detroit’s 48th.

Note 2: At the peak of the housing bubble, affordability deteriorated to a moderately unaffordable 3.1 in Atlanta. Atlanta had been among the high income world’s fastest-growing metropolitan areas for at least three decades, but slowed briefly during the Great Financial Crisis. Growth has returned, with Atlanta ranking third in net domestic migration among US metropolitan areas with more than 5 million population.

—-

Photograph: Hong Kong (by author)

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”