“Angry Gran” was one of the top mobile app games of 2012 globally. In it, the gamer assumes the persona of a grandmother gone rogue: Angry Gran is angry and needs money! Whack your enemies like piñatas until the cash comes flying out… The objective? Support Gran’s ‘active’ and ‘financially savvy’ retirement by assaulting unsuspecting passers-by with various weapons. If the assault succeeds, Gran steals their money and the gamer’s score rises; if the assault fails, Gran sprains her back and the gamer’s progress is delayed. Given the aging global demographic, one wonders if this sense of humour is best categorized as fiction, or as paradoxical truth?

Gran gone rogue – an emerging trend? – In Japan, there’s more truth than fiction to angry Gran (and, presumably, Gramps). Its elderly population is 23% of the total; that’s the highest in the world. The National Policy Agency notes that the overall crime rate has fallen steadily, with the exception of offenses committed by the elderly. Theft offenses by the elderly increased 98% in the past eight years, from about 17,000 to more than 34,000. Previously, it was suggested that elderly offenders committed non-violent offenses due to loneliness, social isolation and poverty. But a more brutal streak is emerging, too: Elderly offenders of assault-related crimes increased a startling 570%, from 348 to 2,337.

In 2008, Japan’s Ministry of Justice dedicated an entire section to elderly offenders in its annual white paper on crime, that is now a regular feature. In recognising the need for additional analysis, the Ministry cited an increase in the proportion of elderly offenders in each stage of the criminal justice system, which was disproportionately higher than the increase in the elderly within the total population.

While the numbers are low, the rate of increase in elderly offenders raises a chilling prospect. Will an aging demographic result in a “geriatric crime wave”? It does not seem to be the case in the US: the national increase in elder arrests has not been disproportionate to increases in the national crime rate. Contribution to the national crime rate by the elderly remains low, with swings in, for example, the US murder rate largely accounted for by the percentage of young adults 15 – 29 years old.

But Japan’s situation is not isolated. Other countries also show divergences from the usual age-crime assumptions. In Korea, the number of elderly sex offenders aged 61 or older increased by more than 50% in three years, beginning in 2008.

In a 1990s report from Canada’s correctional services, 72.8% of older offenders were first time offenders admitted late in life; their rate of sexual crimes, homicide and manslaughter was double that of young offenders. In the Netherlands, older age groups were also over-represented in organized crime offenses, where 33% were over 40, and 76% over 30.

Health and a swinging hatchet: Declining elderly disability – Florida, which is demographically similar to Japan, offers other insights. Between 1980 and 1998, there was a marked increase in elderly offenders committing forcible sex offenses, robbery and aggravated assault. The nature of such crimes indicates that these elderly offenders are not frail, but rather, somewhat able-bodied.

Data remains scarce, but within a similar time frame across the US, severe disability among those 65 years and older declined approximately 25%. Studies also show that better childhood health reduces the risk factors for old-age disability and other serious illnesses. The future Gran who was born in the 1970s may eventually be quite sprightly in comparison to the one born in the 1920s.

So the likelihood that Gran is healthy enough to grab the hatchet and swing it with full force has increased. It was recently reaffirmed that personality characteristics which predict criminal activity in young people may apply to older people, as well. Late-life stressors such as loneliness and caregiving situations gone bad are specific to older offenders, and, equally worrying are the onset of age-related mental illness, and the lack of early detection and management. For instance, family members have almost no recourse against an elderly relative who owns a firearm. Yet in a study of elderly charged with violent offenses and referred for psychiatric evaluation in South Carolina, 78.3% used guns and 40.7% of victims were family members – and nearly half of the perpetrators presented with dementia.

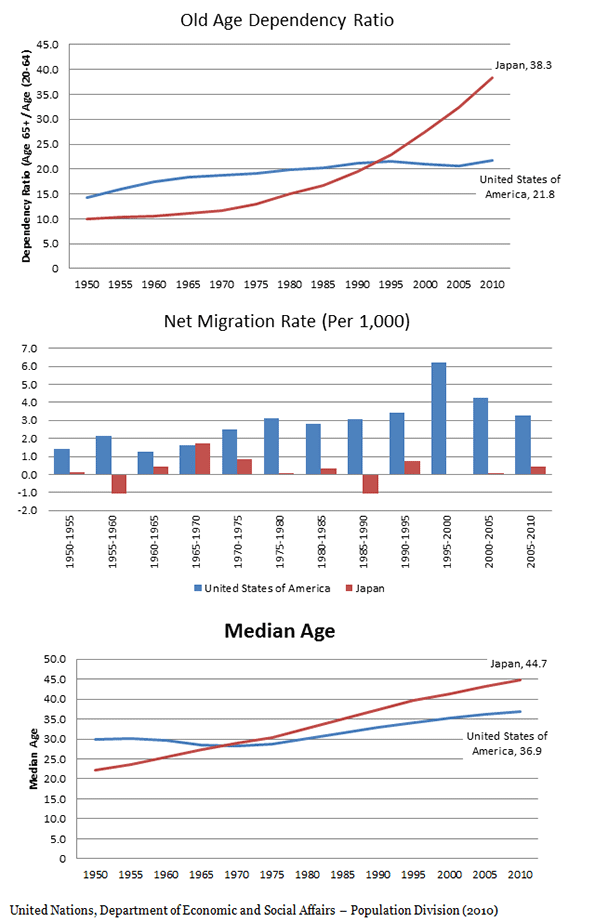

We’re not Japan – In 2011, Wendell Cox and I wrote about aging global demographics. The differences between the US and Japan were notable. Currently, Japan’s old age dependency ratio (the ratio of those aged over 65 to those from 20 – 64) is 76% higher than that of the US. But the US median age continues to rise: At 36.9 years it is currently only 8 years lower than Japan’s 44.7 years. Given the aging global demographic, migration is unlikely to offset these rises indefinitely. In the coming years, will age-crime assumptions be challenged in the US too?

The Future: An Aging Criminal Class? – Sixteen percent (246,600) of the US prison population is age 50 and older. The burgeoning elderly prison population has been attributed to longer prison sentences, brought on by more punitive sentencing principles during the 1970s and onwards. Yet there appear to be few studies on elderly or older prisoner release, rehabilitation and recidivism.

And stemming the inflow of older offenders into prisons is also necessary. In Florida, admissions of offenders over 50 increased 205%, from 1,130 in 2000 to 3,452 in 2010 – from just 4.4% to almost 10% of total admissions. Despite an increased need to dedicated research on the behaviour and characteristics of older groups, a proportion of whom will reoffend in their golden years, the current work focuses largely on juveniles. In Japan, 25% of offenders in their late 40s become repeat offenders within 10 years of their first conviction, almost five times more frequently than those who are first convicted in their early 20s.

Little is understood about what motivates the Colt-wielding Granny or Gramps. Older offenders present new challenges for justice systems, and for society as a whole. The opportunity now is to prevent criminal acts by the elderly. Discussion and analysis of geriatric crime is very much warranted.

Emma Chen was a Senior Strategist at the Centre for Strategic Futures, Singapore. She is currently pursuing postgraduate studies.