Over the last four years, emissions in the United States declined more than in any other country in the world. Coal plants and coal mines are being shuttered. That’s not from increased use of solar panels and wind turbines, as laudable as those technologies are. Rather it’s due, in large measure, to the technological revolution allowing for the cheap extraction of natural gas from shale. By contrast, Europe, with its cap and trade program, and price on carbon, is returning to coal-burning.

Could President Obama, during his second term in office, turn this homegrown success story into paradigm-shifting climate strategy? In a speech we gave to the Colorado Oil and Gas Association yesterday, we argue that, after a season of ugly ideological polarization, politicians, environmentalists, and the gas industry have a chance to hit the reset button on energy politics.

This will require the natural gas industry to clean up its act, accepting better regulations, cracking down on bad actors, and preventing the leakage of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. It will require environmentalists to consider whether there might be a different path to significant emissions reductions from the one they have pursued over the last 20 years. And it will require Left and Right to put a halt to the tribalism that has characterized the national debate over climate and energy.

— Michael and Ted

Uniting a Fractured Republic

Innovation, Pragmatism, and the Natural Gas Revolution

by Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger

In 1981, George Mitchell, an independent Texas natural gas entrepreneur, realized that his shallow gas wells in the Barnett were running dry. He had millions of sunk investment in equipment and was looking for a way to generate more return on it. Mitchell was then a relatively small player in an industry that by its own reckoning was in decline. Conventional gas reserves were limited and were getting increasingly played out.

As he considered how he might save his operation, Mitchell turned his attention to shale. Drillers had been drilling shale since the early 19th Century, but mostly they drilled right through it to get to limestone and other formations. Dan Jarvey, a consultant to Mitchell at the time, told us, "When you look at a [gas drilling] log from the 1930s or 1950s or 1970s it is noted as a ‘gas kick’ or ‘shale gas kick.’ Most categorized it as ‘It’s just a shale gas kick’ – as in, ‘to be expected, but to be ignored.’"

As Mitchell embarked on his 20-year quest to crack the shale gas code, most of his colleagues in the gas industry thought he was crazy. But Mitchell persisted and his efforts would ultimately culminate in today’s natural gas revolution.

In doing so, Mitchell upended longstanding assumptions about the future of energy. Just a few years ago, the convention wisdom was that no source of electricity could be cheaper than coal. Today, in the U.S., natural gas is cheaper. As a result, coal’s share as a percentage of electricity generated went from over 50 percent in 2005 to 36 percent in 2012. While global coal use continues to rise, the U.S. is at present leaving much of it in the ground. Meanwhile, estimates of recoverable natural gas results in the United States have nearly doubled, growing from 200 trillion cubic feet in 2005 to 350 trillion cubic feet today.

The implications for those of us concerned about climate change are also significant. Leaving coal in the ground has been the longstanding goal of those of us concerned about global warming. Natural gas releases emits 45 percent fewer carbon emissions. In large part due to the glut of natural gas, U.S. carbon dioxide emissions will have declined more in the United States than in any other country in the world between 2008 and 2012 — an astonishing 500 million metric tons out of 6 billion, according to the Energy Information Administration.

While we don’t imagine that any of this is news to most of you in this audience, there is another part of the story that might be. That is the story of the ways in which both the gas industry and the federal government helped Mitchell along the way. In these intensely polarized times, when it seems that almost everyone imagines that either government or corporations are the enemy, and it seems impossible to imagine that the two might actually work together to further the public interest, there are important lessons here too.

1.

As Mitchell considered trying his hand at shale, he cast about to see what was known at the time about how to get gas out of shale. A geophysicist who worked with Mitchell recalled telling him that, "It looks similar to the Devonian [shale back east], and the government’s done all this work on the Devonian."

The work Mitchell’s geophysicist was referring to was the Eastern Gas Shales Project, which was started in 1976 by President Ford. The Shales Project was just one of several aggressive government-led efforts to accelerate technology innovation to increase oil and gas production. Already in 1974 the Bureau of Mines was funding the study of underground fracture formations, enhanced recovery of oil through fluid injection, and the recovery of oil from tar sands. One year later, the government funded the first massive hydofracking at test sites in California, Wyoming and West Virginia, as well as "directionally deviated well-drilling techniques" for both oil and gas drilling.

The mandate from Congress was for government scientists and engineers to hire private contractors rather than do the work in-house. This was consistent with the tradition of the Bureau of Mines, which would set up trailers around the country to support oil, coal and gas entrepreneurs. This strategy contrasted with the government’s nuclear energy R&D work, which had been hierarchical since its birth in the military’s Manhattan project. This decentralization proved wise, as it ensured that the information would rapidly reach entrepreneurs in the field and not gather dust inside of a federal bureaucracy.

From early on, Mitchell and his team relied heavily on information coming out of the Eastern Gas Shales project. "We were all reading the DOE papers trying to figure out what the DOE had found in the Eastern Gas Shales," Mitchell geologist Dan Steward told us, "and it wasn’t until 1986 that we concluded that we don’t have open fractures, and that we were making production out of tight shales."

Through the 1980s, Mitchell didn’t want to ask the government – or the Gas Research Institute, which was funded by a fee on gas pipeline shipments to coordinate government research with experiments being conducted by entrepreneurs in the field – for help because he worried that he wouldn’t be able to take full advantage of the investment he was making in innovation.

But by the early 1990s Mitchell had concluded that he needed the government’s help, and turned to DOE and the publicly-funded Gas Research Institute for technical assistance. The Gas Research Institute, which had worked with other industry partners to demonstrate the first horizontal fracks, subsidized Mitchell’s first horizontal well. Sandia National Labs provided high-tech underground mapping and supercomputers and a team to help Mitchell interpret the results. Mitchell’s twenty-year quest was also made possible by a $10 billion, 20-year tax credit provided by Congress to subsidize unconventional gas, which was too expensive and risky for most private firms to experiment with otherwise.

By 2000, the combination of technologies to cheaply frack shale were firmly in place. The final piece of the puzzle was the sale of Mitchell Energy to Devon Energy, which scaled up the use of horizontal wells. Over the next ten years the use of this combination of technologies would spread across the country, resulting in today’s natural gas glut.

Though the collaboration between Mitchell and the government was one of the most fruitful public-private partnerships in American history, it was mostly unknown until we started interviewing the key players involved around this time last year.

After our findings were verified by other researches and reporters, including the New York Times and the Associated Press, some in the oil and gas industry, like T. Boone Pickens, have tried to downplay the government’s role.

But the pioneers of this technology have been forthright. "I’m conservative as hell," Mitchell’s former Vice President Dan Steward told us, but DOE "did a hell of a lot of work and I can’t give them enough credit… You cannot diminish DOE’s involvement." Fred Julander said, “The Department of Energy was there with research funding when no one else was interested and today we are all reaping the benefits."

2.

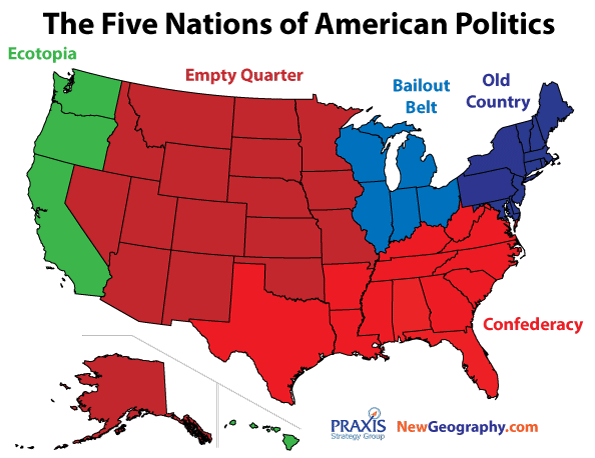

Today marks the end of one of the most divisive chapters in American political history. There is more partisan polarization in Congress than at any time since Reconstruction. There are vanishingly few swing voters. And the ideological divide between liberals and conservatives at times appears unbridgeable.

One of the most insidious aspects of today’s political polarization is the way gross exaggerations turn into ossified caricatures. Left and Right view the other as ignorant, insane, or immoral.

From the Right we have heard that President Obama is taking the country to socialism, and that Big Government is destroying the American dream. From the Left we have heard that Governor Romney would have exported all our jobs to China, and turn Congress over to Big Business. Where this downward spiral takes us is to the conclusion that America is fundamentally broken. The two great institutions of American life — business and government — are viewed by one side or the other as corrupt and nefarious.

Few issues have become more polarizing than energy. Both sides have taken ever more extreme positions. Prominent conservatives have exaggerated both the size of Obama’s clean energy investments and the number of bankruptcies. They have described global warming and other environmental problems as either not happening or not worth worrying about. Some environmentalists have taken the opposite tack, exaggerating the negative impacts of gas drilling, downplaying the benefits, and accusing anyone who disagrees with them of being on the take.

As we say in California — everyone needs to chill out. There is too much at stake for America, our environment, and our economy, for such hyper-partisanship to continue.

In our rush to point fingers and interpret everything in catastrophic terms, we have lost sight of the fact that we are the richest nation on earth, and one with improving environmental quality, precisely because the private sector and the government have worked so well together. The failures of Big Business and Big Government should be put in their appropriate historical context.

When the Colorado Oil and Gas Association asked us to give this speech at its conference the day after the election, we agreed on two conditions: that we pay our own way and that COGA invite local environmental and elected leaders to attend. We are glad to see them in the audience, because we need a common dialogue.

As two individuals who came out of the environmental movement, where we spent most of our careers, we are best known for our writings calling for reform and renovation of green politics. In particular, we have advocated that environmentalists drop their apocalyptic rhetoric, which is self-defeating and obscures the very real environmental problems we face.

And we have argued that environmentalists have been overly focused on regulations, when our focus should also be on revolutionary technological innovation, which is needed to make clean energy and other environmental technologies much cheaper, so that all seven going on 10 billion humans can live modern, prosperous lives on an ecologically vibrant planet.

But our work has also focused on reminding private investors and corporate executives of the critical role played by the government in creating our national wealth. While economists have long recognized that innovation is responsible for most of our economic growth, few realize that many of our world-changing innovations would have been unlikely to occur without government support. A short list of recognizable technological innovations includes interchangeable parts, computers, the Internet, jet engines, nuclear power and every other major energy technology.

Consider the information revolution. The government funded the R&D and bought 80 percent of the first microchips. The Internet started out as a federally funded program to connect networks of computers of government. Every major technology in the iPhone can be traced to some connection with government funding. The driver-less robot car that Google has invented relies on technologies that come out of government innovation programs.

While high tech executives who are our age or younger are unaware of the government roots of the IT revolution, the old-timers of Silicon Valley do, and frequently expresses their gratitude for it.

While interviewing the participants of the shale gas revolution, we were struck by how much respect and deference each side gave to the other. In many cases the government scientists and engineers acted as consultants to private firms like Mitchell’s — "We never forgot who the customer was," said Alex Crawley, who ran the DOE’s fossil innovation program for many years.

As environmentalists, we were taught to be suspicious of such cozy relationships between industry and government workers, that government could not simultaneously promote industry while also attempting to regulate it. But when it comes to technology innovation, those cozy relationships, and the revolving door between government agencies, whether DoD or DoE, and private companies like Mitchell Energy, are absolutely essential to allowing knowledge to rapidly spillover and flow throughout the sector.

And yet, there is also an important role for regulation, not only to protect the public from accidents and environmental degradation, but also to improve technologies and promote better practices throughout the industry. Wise regulation in the long run promotes, rather than hinders, the spread of new technologies and new industries, and this has never been more true than in the case of fracking. While US gas production has taken off, many European nations banned fracking for fear of the local environmental impacts and have started to return to burning coal.

Last August, George Mitchell and New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced they would fund a large effort by the states to establish better fracking practices. They called for stronger control of methane leaks and other air pollution, the disclosure of chemicals used in fracking, optimizing rules for well construction, minimizing water use and properly disposing of waste water, and reducing the impact of gas on communities, roads, and the environment.

You would be hard pressed to find very many Americans who would call those reforms unreasonable. They are the kinds of things that die-hard anti-fracking activists and much of the natural gas industry could agree to. And indeed, states like Colorado, and environmental groups like the Environmental Defense Fund, deserve credit for bringing regulators and the gas industry together to improve practices. By squarely addressing the methane leakage problem, and reducing the local environmental impacts, the government and the industry can make natural gas an even more obviously better alternative to coal.

And the good news is that reducing methane leakage is something the industry already knows how to do. Little innovation is required to make sure that old pipelines are not leaking, and that new cement jobs are done properly. Similarly, responsible disposal of fracking fluids is not rocket science, it is something that the oil and gas industry does routinely in other contexts. Promising efforts are also underway to develop more environmentally sound fracking fluids and to further minimize water usage.

There are costs, of course, associated with all of these efforts. But if the history of fracking proves anything, it is that costs will come down quickly. Indeed, if history is any guide, we will see great improvements to fracking technologies and techniques over the next 30 years that will be mutually beneficial to the industry, the public, and the environment, for the history of the shale gas revolution has been a history of incremental improvements to the technology. The water intensity of fracking, for instance, was originally not an environmental problem for drillers but an economic one. Only once Mitchell and others developed methods that required vastly less water to crack the shale did fracking become economically viable.

For all of these reasons, we should both regulate fracking fairly and effectively, and also continue to support innovation to improve unconventional gas technologies. Doing so will help assure a future for gas beyond the precincts in which it is already well established. We also need to support innovation in new gas technologies well beyond fracking practices to include carbon capture and storage, which is more viable economically and technologically for gas than for coal, because gas plants are more efficient, and the emissions stream much purer. In a world in which there may remain significant obstacles to moving entirely away from fossil fuels, gas CCS looks much more viable than coal CCS. As such, we need government and the gas industry to work together to demonstrate carbon capture technologies at sites around the country, similar to how we conducted the Eastern Gas Shales Project.

And the gas industry should support innovation beyond natural gas to include support for innovation in renewables, nuclear and other environmentally important technologies. Championing energy innovation more broadly would do more for the industry than the millions it is currently spending on slick 30-second TV ads and will remind Americans that supporting gas as well as renewables is not a zero sum proposition. Getting our energy from a diversity of sources is in the national interest and gas will thrive for a long time regardless of the energy mix. Moreover, until we have cheap utility scale storage, renewables need cheap gas for backup.

For all of this to happen, the gas industry and environmentalists alike must change their posture toward regulation. While it is the goal of a small number of us to rid the world of particular practices, whether shale-fracking or atom-splitting, most of the rest of us want to improve them.

Over the last 10 years, our message to the environmental movement has been that it must change its attitude toward technological innovation. Technologies are not essentially good or bad but rather in a process of continuous improvement. But there is another side to that story that industry must remember. Regulations that are often bitterly opposed sometimes end up being a boon for industry, paving the way for the broad acceptance of new technologies and pushing firms to improve those technologies in ways that make them more economical as well as more environmental.

In closing we’d like to invoke the title essay of our last e-book, “Love Your Monsters,” which was written by one of our Senior Fellows, a well-known French anthropologist named Bruno Latour. In the essay, Latour monkey-wrenches the Frankenstein fable. The sin of Dr. Frankenstein, according to Latour, was not creating the monster, but rather abandoning him when he turned out to be flawed. We must learn to love our technologies as we do our children, he concluded, constantly helping and improving them. In so doing, we too become all the wiser.

As we consider the implications of the gas revolution for the future of both our energy economy and our environment, we should commit ourselves to the larger effort of improving our technological creations. In so doing, the gas industry and the environmental movement might together update the concept of sustainability for the 21st Century. We should seek not to put limits on the aspirations of 1.5 billion people who still lack access to electricity, nor on the billions more yearning for enough to power washing machines and refrigerators. Nor should we want to sustain today’s energy technologies to be used in perpetuity. Rather, we should embrace technological innovation as the key to creating cleaner and better substitutes to today’s energy and non-energy resources alike so that we might sustain human civilization far into the future.

a collection of historical travel essays. His next book is “Whistle-Stopping America”.