I’ve had it in my head for over a year now to do an in-depth exploration of Chicago, a project I’ve called “State of Chicago.” This is the first a series of pieces that expand on the themes in my recent article “The Second-Rate City?”

First, I’d like to list three reasons why I wrote that piece:

1. To bring to the attention of Chicago the very poor statistical performance of the city on basic demographic and economic measures.

2. To write a corrective to the many national puff pieces that have been written on the city that totally overlooked its real and serious problems.

3. To lay out some frames that I had on the underlying causes that are different from the typical explanations, in particular the excessive focus on “global city” and the “cost of clout.”

As it turns out, Rahm Emanuel’s own economic plan and the OECD report beat me to the punch on point #1. As a lot of what I wanted to accomplish with State of Chicago was data oriented, my project is now much less ambitious than I’d originally intended since Chicago’s leaders are now, fortunately, owning up to the problems.

The Fall of Chicago

Today I want to start out by giving the prequel to my article: Chicago’s Rust Belt decline and subsequent comeback, particularly in the 90s. I think everybody knows that cities had a rough 70s and early 80s. It was the “Rotten Apple” era in New York, for example, a time of needle parks, mugger money, graffiti trains, a brush with bankruptcy, and much more.

Chicago had a similar rough patch. When Richard Longworth (now of Caught in the Middle and Global Midwest fame) returned to Chicago in 1976 from many years overseas as a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, it was to a grim, decaying city that, like so many big cities in America at the time, clearly was a city that did not work.

This was perhaps best symbolized by the city’s inept response to the Blizzard of ’79, which left the city paralyzed for days. Mayor Michael Bilandic’s blizzard response was widely credited for his subsequent re-election defeat. Old mayor Richard J. Daley’s City Hall alliance with business had preserved the Loop as a powerful, if somewhat drab, business district while so many other Midwest downtowns fell into ruin. But otherwise Chicago was a troubled, declining city covered by a veneer of boosterism.

In 1981 Longworth wrote a damning four part, front page series for the Chicago Tribune called “A City on the Brink” drawing a powerful portrait of a city in crisis. He noted that, “Chicago has become an economic invalid. The situation may be permanent.” The Economist, in a far cry from its praise in the 2000s, described the city as having little more than a “facade of downtown prosperity.”

The city was losing people, losing businesses, and losing jobs – even in the Loop. Manufacturing was collapsing and the middle class was fleeing, leading to neighborhood decline and eroding the city’s tax base, which in turn degraded the city services residents had come to expect and demand. The decline in services and neighborhoods drove more people way, which led to further declines, perpetuating a vicious cycle.

University of Illinois at Chicago Professor Pierre de Vise predicted, “I see very little hope for locating economic activities here again.” And a local business executive added, “Is the city being annihilated? It’s probably inevitable.” While careful to note that Chicago was not at the point of New York City’s brush with bankruptcy nadir, Longworth noted it was headed that direction and glumly asked, “What happens when a major city becomes a backwater?”

The city was failing on nearly every measure. I was struck by how similar Longworth’s litany of statistics were to my own. There was a big different however: back then things were way worse. Today the problems of Chicago take place against a backdrop of many areas of strength in the urban core and a secular uptrend in the fortunes of cities. Given that Chicago has come back from far more dire circumstances than it faces today, there’s reason for optimism in the present.

Chicago Reborn

As I noted in City Journal, during the 90s (probably starting in the late 80s), Chicago had a massive comeback. It gained people, it gained jobs, and the core reasserted itself. I moved to Chicago in 1992 when only a few select lakefront precincts were really gentrified. Though I lived in Lincoln Park, I was told not to move west of Racine, not because it was dangerous, but because it was dead. The area where I used to live near Belmont/Ashland/Lincoln was completely boarded up except for the Army-Navy surplus store. Recruiters for my company tried to sell me on the city by telling me it was now a location of the uber-hip coffee chain Starbucks. I watched vast tracts of the city transformed before my eyes. The 90s boom was real. I saw it. I felt it.

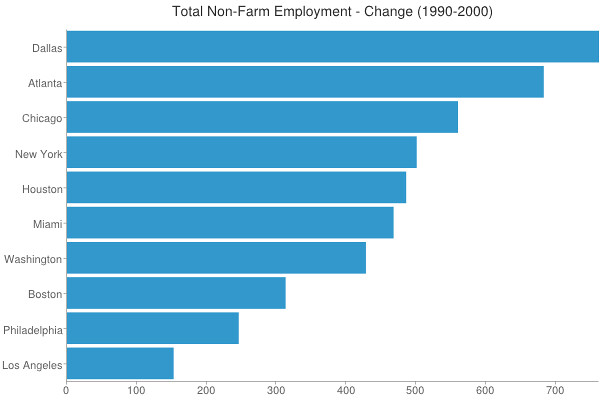

It also showed up in the data. I don’t want to go too crazy, but I wanted to look at some economic statistics. First, I want to look at metro area job growth in the 1990s for selected cities. I’ll show the percentage gains in a moment, but here’s the raw job growth for the ten largest US metros during the 1990s. (Top ten selected based on today’s 2010 census population).

Note: Data in thousands

Chicago actually had the third highest total job growth. Not only did metro Chicago outgrow New York and crush LA (which got bruised by the “peace dividend”), it actually added more total jobs than Houston, everybody’s darling today. Wow. And more than currently booming Washington, DC. In short, Chicago beat out its mature tier one peers while holding its own with the emerging boomtowns. Very impressive.

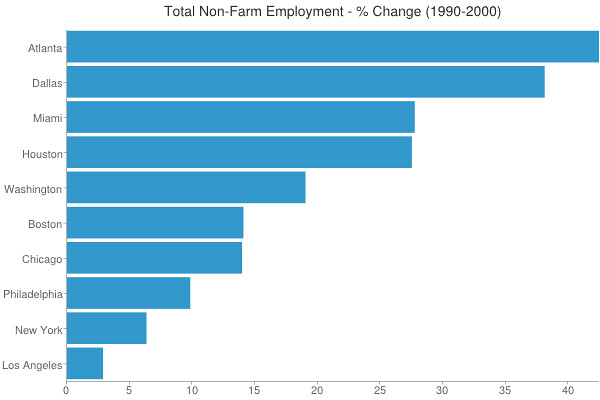

Here’s the percentage view:

Not as impressive vs. the emerging cities, but Chicago held its own with Boston (a big beneficiary of the dotcom boom) and more than doubled up traditional peers New York and LA. I think it’s fair to label Chicago an outperformer here.

Let’s do a quick look at unemployment rates for the big three:

As you can see, Chicago metro had a much lower unemployment rate than NYC or LA during most of the 90s. Since unemployment rate is available at the municipal level, here’s a quick look at the big three core cities. We’ll see again that even at the municipality level, the city of Chicago had a lower unemployment rate:

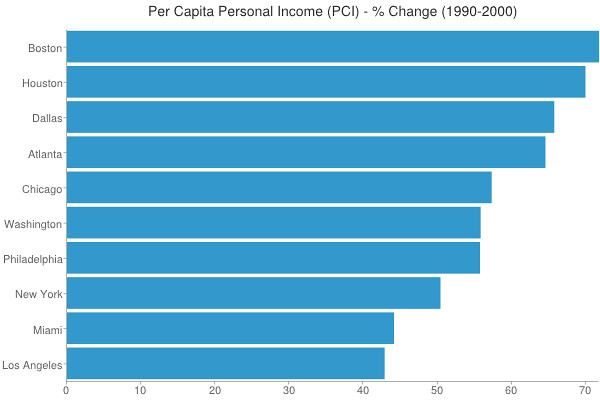

So in terms of quantitative measures, Chicago was winning in the 90s. But it also seemed to do well qualitatively. I don’t have GDP data going back to the 90s, but I do have per capita personal income. Here’s how the top ten cities fared:

Boston topped out, perhaps to be expected from the dotcom boom. But Chicago beat NYC and LA again, and also Washington, DC. (Interestingly, the southern boomtowns that did well on this metric in the 90s mostly got killed on it in the 2000s, Houston excepted).

So I think it’s fair to say that compared to its large mature peers, Chicago economically was the winner (or at least near the top depending on who you put in there) during the 1990s, along with Boston. This is the type of performance Chicago is capable of delivering.

But beyond the statistical measures, there were many qualitative improvements as well. For example, Chicago was really the early leader in quality of space. After Mayor Daley’s famous trip to Paris, he came back and encased the city in wrought iron. He also put in miles of streetscapes, with median planters, new streetlights and the like. (I happen to think the aesthetic style of these was not appropriate to Chicago, but they clearly upgraded the city in a big way). The CTA saw a brand new L line open to Midway Airport. New cultural facilities blossomed. For example, both the Chicago Symphony and the Lyric Opera undertook $100+ million building projects. And Daley even brought political stability back to the city after the turbulence Bilandic-Bryne years and the racially driven “Council Wars” of the 1980s.

In a post-Cold War global order, Chicago also emerged as a global city. No longer just a superpower of the American interior, Chicago came to play a critical role in the global economy, through its derivatives exchanges, its professional services complex, and its status as a transport and cultural hub. Globalization became the lens through which the city sees its role in the modern economy, and with some justification. By 2010, Foreign Policy magazine ranked Chicago as the sixth most important global city in the world, for example. Chicago began to regard itself no longer as merely the “Second City,” but as a global player in its own right.

So in the 1990s, Chicago was riding high. Little did the city know that with the dotcom collapse and the national economic trends of the 2000s, the city was about to enter a tailspin. But there was clearly a lot of real progress and change in the city and a lot for the city to feel good about and be proud of. Chicago was the big city champion of the 90s.

I don’t want that story to get lost and people to think I’m just picking on Chicago. I’m happy to shout out its accomplishments when merited. But when things aren’t going so well, the city likewise deserves people who are willing to tell the truth.

In the next installment, we’ll expand a bit on the troubles.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the founder of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile, where this piece originally appeared.

Chicago skyline photo by BigStockPhoto.com.