There has been lots of data indicating that domestic manufacturing is regaining some vigor after years of wasting away. Brookings’ Martin Neil Baily and Bruce Katz, writing in the Washington Post, noted:

Manufacturing employment, output and exports are headed in the right direction: In April, the number of U.S. manufacturing jobs was up 489,000 from the January 2010 low of 11.5 million. The Institute of Supply Management’s manufacturing index has shown 33 consecutive months of expansion.

Some of this growth may be due to re-shoring efforts. This CNBC article mentions Chesapeake Bay Candle, which outsourced much of its manufacturing workforce 17 years ago and is starting to bring them back. Here is an excerpt:

A survey by the Boston Consulting Group in February found more than one-third of U.S.-based manufacturing executives at companies with sales greater than $1 billion are either planning or considering bringing production back to the United States from China.

To inform the discussion a bit more, we tapped into our database and pulled all of the 4-digit NAICS manufacturing sectors (86 in all) to learn more about the recent growth. From the end of 2010 to the end of 2011, our data tells us that the 4-digit manufacturing sectors added just over 200,000 jobs. NOTE: This is less than the Brookings research shows, but we are likely looking at slightly different timeframes and datasets.

Job Winners

The industries that gained the most jobs in one year didn’t necessarily go through the roof, but considering what they went through over the previous nine or 10 years, it is safe to say that the trends we are seeing now are pretty significant. Prior to 2010, pretty much every manufacturing sub-sector experienced significant decline. Domestic machinery manufacturing especially stands out. Several sub-sectors gained a healthy number of jobs last year.

The industries that gained the most jobs in one year didn’t necessarily go through the roof, but considering what they went through over the previous nine or 10 years, it is safe to say that the trends we are seeing now are pretty significant. Prior to 2010, pretty much every manufacturing sub-sector experienced significant decline. Domestic machinery manufacturing especially stands out. Several sub-sectors gained a healthy number of jobs last year.

- Ag, construction and mining machinery manufacturing (NAICS 3331) gained nearly 14,000 new jobs (7% employment growth) and now employs 218,000. From 2001 to 2009, this industry declined by 3%, shedding 7,500 jobs.

- Other machinery manufacturing (NAICS 3339, a catch-all industry) gained 12,000 new jobs (5% employment growth) and now employs 237,000. From 2001 to 2009, this industry declined by 26%, shedding 85,000 jobs.

- Metalworking machinery manufacturing (NAICS 3335) gained 11,000 new jobs (7% employment growth) and now employs 166,000. From 2001 to 2009, this industry declined by 37%, shedding 91,000 jobs.

All told, these three sectors added some 37,000 jobs in one year, which is great considering that they actually lost 184,000 over the previous nine years.

Of all the 4-digit sectors, machine shops (NAICS 3327) gained the most new jobs in one year — about 22,000 jobs or 7% employment growth. There are now some 330,000 employed in this sector. From 2001 to 2009, this industry declined by 11% and shed 38,000 jobs.

Motor vehicle part manufacturing (NAICS 3363) added 20,000 jobs, which was 3% growth. There are now 435,500 employed in this industry. From 2001 to 2009, this industry declined 46% (a loss of 356,000 jobs).

Semiconductor manufacturing (NAICS 3344) did well by adding 17,000 new jobs, which represents 4% growth. There are now 386,000 jobs in this sector. From 2001 to 2009, this industry declined by 41% (a loss of 266,000 jobs).

Finally, aerospace products manufacturing (NAICS 3364) gained 13,000 jobs, which is 3% growth. The current job count stands at 488,000. From 2001 to 2009, this industry declined by 3% (a loss of 14,000 jobs).

The big thing to note here is how much of this is related to advanced manufacturing.

Fastest-Growing

Audio and visual equipment manufacturing (NAICS 3343) had the fastest overall growth from 2010-2011. The big thing to note is that from 2001-2009 the industry actually lost more than half (53%) of its total workforce, a total of 25,000 jobs. During 2011, it managed to gain back 12% or 2,360 jobs. We’d say that a one-year rebound like that is great news after such a huge loss.

Audio and visual equipment manufacturing (NAICS 3343) had the fastest overall growth from 2010-2011. The big thing to note is that from 2001-2009 the industry actually lost more than half (53%) of its total workforce, a total of 25,000 jobs. During 2011, it managed to gain back 12% or 2,360 jobs. We’d say that a one-year rebound like that is great news after such a huge loss.

After that, steel product manufacturing (NAICS 3312), which lost 17,000 jobs (-25%) since 2001, had 10% employment growth and added over 5,000 jobs from 2010-11, and foundries (NAICS 3315), which lost 86,000 jobs (-43%), grew by 9% and added nearly 10,000 jobs.

Highest-Paying

With an average industry earnings level of $140,000 per year (keep in mind this is averaging the wages and salaries of all workers in the industry together), computer and peripheral equipment manufacturing (NAICS 3341) has the highest earnings. From 2001 to 2009, the industry lost 41% of its workforce or 118,000 jobs. In 2011, it grew by 6%, adding 9,400 jobs.

With an average industry earnings level of $140,000 per year (keep in mind this is averaging the wages and salaries of all workers in the industry together), computer and peripheral equipment manufacturing (NAICS 3341) has the highest earnings. From 2001 to 2009, the industry lost 41% of its workforce or 118,000 jobs. In 2011, it grew by 6%, adding 9,400 jobs.

After that comes pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing (NAICS 3254) and petroleum and coal products manufacturing (NAICS 3241), which both average about $102,000 per year. Neither of these final two sectors grew last year.

Biggest Losers

Despite the overall growth, some industries are still in decline.

Despite the overall growth, some industries are still in decline.

Printing and related support activities (NAICS 3231) lost 21,000 jobs in one year (-4%), which was the biggest loss of any 4-digit sector. The biggest loser in percent terms was apparel knitting mills (NAICS 3151), which lost 10% of its workforce.

Below is the complete data table of all 86 sectors.

| Description |

2010 Jobs |

2011 Jobs |

Change |

% Change |

2011 Avg. Annual Wage |

| Total |

11,487,828

|

11,690,458

|

202,630

|

0.02

|

$59,138

|

| Machine Shops; Turned Product; and Screw, Nut, and Bolt Manufacturing |

311,123

|

332,817

|

21,694

|

7%

|

$48,785

|

| Motor Vehicle Parts Manufacturing |

415,180

|

435,493

|

20,313

|

5%

|

$55,050

|

| Semiconductor and Other Electronic Component Manufacturing |

369,879

|

386,407

|

16,528

|

4%

|

$88,772

|

| Agriculture, Construction, and Mining Machinery Manufacturing |

203,837

|

217,594

|

13,757

|

7%

|

$70,602

|

| Aerospace Product and Parts Manufacturing |

475,009

|

487,886

|

12,877

|

3%

|

$87,430

|

| Other General Purpose Machinery Manufacturing |

225,257

|

237,315

|

12,058

|

5%

|

$61,266

|

| Metalworking Machinery Manufacturing |

155,031

|

166,188

|

11,157

|

7%

|

$53,903

|

| Foundries |

111,056

|

121,031

|

9,975

|

9%

|

$50,014

|

| Computer and Peripheral Equipment Manufacturing |

158,879

|

168,224

|

9,345

|

6%

|

$140,228

|

| Other Fabricated Metal Product Manufacturing |

245,850

|

254,972

|

9,122

|

4%

|

$55,840

|

| Architectural and Structural Metals Manufacturing |

319,567

|

327,843

|

8,276

|

3%

|

$46,489

|

| Coating, Engraving, Heat Treating, and Allied Activities |

121,460

|

128,481

|

7,021

|

6%

|

$43,415

|

| Beverage Manufacturing |

167,187

|

173,497

|

6,310

|

4%

|

$51,120

|

| Ventilation, Heating, Air-Conditioning, and Commercial Refrigeration Equipment Manufacturing |

125,870

|

132,160

|

6,290

|

5%

|

$49,587

|

| Ship and Boat Building |

123,574

|

129,773

|

6,199

|

5%

|

$56,065

|

| Industrial Machinery Manufacturing |

97,824

|

103,848

|

6,024

|

6%

|

$71,912

|

| Motor Vehicle Manufacturing |

152,736

|

158,707

|

5,971

|

4%

|

$79,407

|

| Engine, Turbine, and Power Transmission Equipment Manufacturing |

90,970

|

96,758

|

5,788

|

6%

|

$72,697

|

| Motor Vehicle Body and Trailer Manufacturing |

108,962

|

114,439

|

5,477

|

5%

|

$44,994

|

| Forging and Stamping |

88,269

|

93,647

|

5,378

|

6%

|

$52,770

|

| Steel Product Manufacturing from Purchased Steel |

52,287

|

57,449

|

5,162

|

10%

|

$57,738

|

| Nonferrous Metal (except Aluminum) Production and Processing |

58,036

|

62,360

|

4,324

|

7%

|

$61,286

|

| Plastics Product Manufacturing |

501,678

|

505,984

|

4,306

|

1%

|

$45,499

|

| Other Electrical Equipment and Component Manufacturing |

117,847

|

122,012

|

4,165

|

4%

|

$58,774

|

| Boiler, Tank, and Shipping Container Manufacturing |

84,588

|

88,693

|

4,105

|

5%

|

$57,507

|

| Converted Paper Product Manufacturing |

281,187

|

284,673

|

3,486

|

1%

|

$53,341

|

| Alumina and Aluminum Production and Processing |

54,054

|

57,539

|

3,485

|

6%

|

$58,638

|

| Medical Equipment and Supplies Manufacturing |

303,297

|

306,341

|

3,044

|

1%

|

$61,515

|

| Electrical Equipment Manufacturing |

134,318

|

136,968

|

2,650

|

2%

|

$63,766

|

| Audio and Video Equipment Manufacturing |

20,042

|

22,402

|

2,360

|

12%

|

$79,151

|

| Basic Chemical Manufacturing |

140,942

|

143,045

|

2,103

|

1%

|

$88,113

|

| Fabric Mills |

54,021

|

56,110

|

2,089

|

4%

|

$41,628

|

| Other Miscellaneous Manufacturing |

263,116

|

265,031

|

1,915

|

1%

|

$46,223

|

| Iron and Steel Mills and Ferroalloy Manufacturing |

85,954

|

87,603

|

1,649

|

2%

|

$73,636

|

| Cut and Sew Apparel Manufacturing |

125,398

|

126,937

|

1,539

|

1%

|

$36,150

|

| Manufacturing and Reproducing Magnetic and Optical Media |

25,002

|

26,425

|

1,423

|

6%

|

$85,820

|

| Other Transportation Equipment Manufacturing |

33,191

|

34,547

|

1,356

|

4%

|

$63,123

|

| Railroad Rolling Stock Manufacturing |

18,402

|

19,752

|

1,350

|

7%

|

$62,647

|

| Office Furniture (including Fixtures) Manufacturing |

96,048

|

97,283

|

1,235

|

1%

|

$44,807

|

| Commercial and Service Industry Machinery Manufacturing |

92,184

|

93,335

|

1,151

|

1%

|

$64,827

|

| Bakeries and Tortilla Manufacturing |

276,593

|

277,718

|

1,125

|

0%

|

$35,578

|

| Rubber Product Manufacturing |

121,591

|

122,587

|

996

|

1%

|

$51,487

|

| Resin, Synthetic Rubber, and Artificial Synthetic Fibers and Filaments Manufacturing |

89,107

|

90,092

|

985

|

1%

|

$78,720

|

| Footwear Manufacturing |

13,148

|

13,863

|

715

|

5%

|

$35,261

|

| Cutlery and Handtool Manufacturing |

40,141

|

40,830

|

689

|

2%

|

$54,144

|

| Paint, Coating, and Adhesive Manufacturing |

55,883

|

56,555

|

672

|

1%

|

$64,627

|

| Pharmaceutical and Medicine Manufacturing |

278,781

|

279,434

|

653

|

0%

|

$102,299

|

| Pesticide, Fertilizer, and Other Agricultural Chemical Manufacturing |

35,755

|

36,407

|

652

|

2%

|

$73,502

|

| Other Leather and Allied Product Manufacturing |

10,934

|

11,557

|

623

|

6%

|

$35,423

|

| Animal Food Manufacturing |

51,602

|

52,172

|

570

|

1%

|

$52,176

|

| Spring and Wire Product Manufacturing |

42,338

|

42,813

|

475

|

1%

|

$45,935

|

| Electric Lighting Equipment Manufacturing |

45,298

|

45,750

|

452

|

1%

|

$52,943

|

| Sugar and Confectionery Product Manufacturing |

66,412

|

66,834

|

422

|

1%

|

$46,306

|

| Hardware Manufacturing |

23,529

|

23,867

|

338

|

1%

|

$53,447

|

| Dairy Product Manufacturing |

130,203

|

130,532

|

329

|

0%

|

$50,968

|

| Leather and Hide Tanning and Finishing |

4,015

|

4,311

|

296

|

7%

|

$44,342

|

| Soap, Cleaning Compound, and Toilet Preparation Manufacturing |

100,840

|

101,045

|

205

|

0%

|

$63,366

|

| Other Nonmetallic Mineral Product Manufacturing |

65,438

|

65,575

|

137

|

0%

|

$49,114

|

| Other Chemical Product and Preparation Manufacturing |

84,148

|

84,261

|

113

|

0%

|

$62,910

|

| Grain and Oilseed Milling |

58,689

|

58,669

|

-20

|

0%

|

$61,858

|

| Sawmills and Wood Preservation |

82,512

|

82,459

|

-53

|

0%

|

$38,074

|

| Textile and Fabric Finishing and Fabric Coating Mills |

36,210

|

36,151

|

-59

|

0%

|

$41,847

|

| Lime and Gypsum Product Manufacturing |

13,483

|

13,408

|

-75

|

-1%

|

$55,548

|

| Clay Product and Refractory Manufacturing |

40,381

|

40,289

|

-92

|

0%

|

$47,440

|

| Other Food Manufacturing |

163,346

|

163,230

|

-116

|

0%

|

$51,728

|

| Other Furniture Related Product Manufacturing |

36,427

|

36,300

|

-127

|

0%

|

$39,650

|

| Pulp, Paper, and Paperboard Mills |

111,661

|

111,144

|

-517

|

0%

|

$74,825

|

| Glass and Glass Product Manufacturing |

78,991

|

78,420

|

-571

|

-1%

|

$51,877

|

| Apparel Accessories and Other Apparel Manufacturing |

13,699

|

12,973

|

-726

|

-5%

|

$35,757

|

| Tobacco Manufacturing |

16,251

|

15,510

|

-741

|

-5%

|

$95,669

|

| Petroleum and Coal Products Manufacturing |

110,968

|

110,014

|

-954

|

-1%

|

$101,861

|

| Fiber, Yarn, and Thread Mills |

29,142

|

28,113

|

-1,029

|

-4%

|

$34,390

|

| Household Appliance Manufacturing |

58,658

|

57,563

|

-1,095

|

-2%

|

$53,698

|

| Other Textile Product Mills |

61,833

|

60,658

|

-1,175

|

-2%

|

$32,955

|

| Fruit and Vegetable Preserving and Specialty Food Manufacturing |

173,410

|

172,057

|

-1,353

|

-1%

|

$42,885

|

| Animal Slaughtering and Processing |

485,619

|

484,061

|

-1,558

|

0%

|

$33,217

|

| Apparel Knitting Mills |

18,521

|

16,702

|

-1,819

|

-10%

|

$35,513

|

| Cement and Concrete Product Manufacturing |

169,820

|

167,189

|

-2,631

|

-2%

|

$46,464

|

| Veneer, Plywood, and Engineered Wood Product Manufacturing |

63,204

|

60,319

|

-2,885

|

-5%

|

$40,514

|

| Navigational, Measuring, Electromedical, and Control Instruments Manufacturing |

407,365

|

404,342

|

-3,023

|

-1%

|

$89,109

|

| Other Wood Product Manufacturing |

193,833

|

190,791

|

-3,042

|

-2%

|

$34,431

|

| Textile Furnishings Mills |

57,300

|

54,100

|

-3,200

|

-6%

|

$36,515

|

| Seafood Product Preparation and Packaging |

36,471

|

33,132

|

-3,339

|

-9%

|

$37,983

|

| Communications Equipment Manufacturing |

115,861

|

111,978

|

-3,883

|

-3%

|

$98,379

|

| Household and Institutional Furniture and Kitchen Cabinet Manufacturing |

223,590

|

218,463

|

-5,127

|

-2%

|

$34,868

|

| Printing and Related Support Activities |

485,717

|

464,657

|

-21,060

|

-4%

|

$43,810

|

State-by-State

As is our custom in posts like this, we like to provide a state-by-state breakdown. To do this we aggregated all 86 industries together and looked at the distribution of these jobs by state. Here are the results.

As is our custom in posts like this, we like to provide a state-by-state breakdown. To do this we aggregated all 86 industries together and looked at the distribution of these jobs by state. Here are the results.

The good news is that 40 out of 51 states (including Washington, D.C.) gained manufacturing jobs.

Oklahoma had the best single year percentage growth (9%) for manufacturing and added nearly 11,000 new jobs. Its current tally of manufacturing jobs is 133,500. Texas added the most new jobs, 23,000, and Michigan was second with 21,000. Current employment levels in each state are 833,000 and 497,000, respectively.

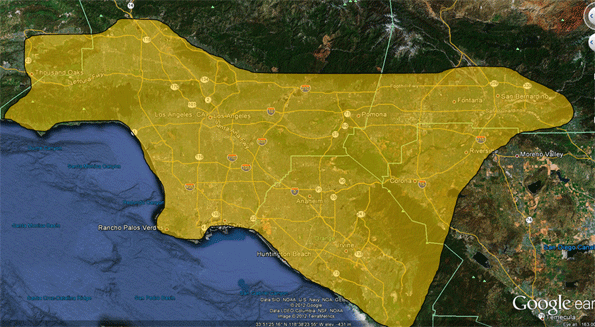

California employs the most, 1.2 million, and grew by 1% or 10,000 jobs in 2011.

Indiana and Wisconsin have the highest concentration of manufacturing jobs. Both are nearly twice the national average, and both employ roughly 450,000 manufacturing workers.

D.C. has the highest pay (averaging nearly $100,000 per year) but very few manufacturing jobs (about 1,000). Massachusetts, which has 260,000 manufacturing jobs and grew by 2% last year, has the second highest average industry earnings ($78,000).

Ten states lost jobs. New Jersey was the biggest loser with -8,100 jobs (3% decline). After New Jersey comes Arkansas, which lost 5,100 jobs (-3%) and New York, which dropped 3,500 jobs (-1%).

The data for each state is below.

| State Name |

2010 Jobs |

2011 Jobs |

% Change |

2011 Avg. Annual Wage |

2010 National Location Quotient (Average is 1.00) |

| Total |

11,487,828

|

11,690,458

|

0.02

|

$59,138

|

|

| Oklahoma |

122,790

|

133,524

|

9%

|

$47,547

|

0.91

|

| Utah |

110,240

|

116,542

|

6%

|

$50,210

|

1.07

|

| Louisiana |

137,263

|

145,003

|

6%

|

$61,321

|

0.83

|

| South Carolina |

207,789

|

219,353

|

6%

|

$51,111

|

1.3

|

| Washington |

254,839

|

266,538

|

5%

|

$68,111

|

1

|

| Michigan |

475,226

|

496,576

|

4%

|

$61,671

|

1.42

|

| Missouri |

243,033

|

253,599

|

4%

|

$50,367

|

1.05

|

| Arizona |

147,905

|

154,034

|

4%

|

$68,224

|

0.7

|

| Iowa |

200,797

|

207,870

|

4%

|

$50,659

|

1.57

|

| South Dakota |

36,963

|

38,208

|

3%

|

$40,746

|

1.04

|

| Idaho |

53,103

|

54,797

|

3%

|

$51,351

|

0.97

|

| Kansas |

159,776

|

164,868

|

3%

|

$51,944

|

1.35

|

| Nebraska |

91,598

|

94,376

|

3%

|

$43,020

|

1.13

|

| Texas |

810,074

|

833,421

|

3%

|

$65,352

|

0.89

|

| Kentucky |

209,263

|

215,162

|

3%

|

$50,610

|

1.33

|

| Wisconsin |

429,233

|

439,887

|

2%

|

$51,403

|

1.83

|

| Ohio |

620,422

|

635,427

|

2%

|

$54,371

|

1.42

|

| Pennsylvania |

560,428

|

572,069

|

2%

|

$55,099

|

1.15

|

| Vermont |

30,796

|

31,431

|

2%

|

$54,094

|

1.17

|

| Illinois |

559,975

|

570,941

|

2%

|

$61,073

|

1.14

|

| Massachusetts |

254,462

|

259,117

|

2%

|

$78,315

|

0.91

|

| Wyoming |

8,710

|

8,858

|

2%

|

$53,439

|

0.35

|

| Tennessee |

298,290

|

303,357

|

2%

|

$52,828

|

1.31

|

| Florida |

307,489

|

311,391

|

1%

|

$52,500

|

0.48

|

| Minnesota |

292,048

|

295,448

|

1%

|

$57,855

|

1.28

|

| North Dakota |

22,548

|

22,803

|

1%

|

$43,695

|

0.68

|

| Indiana |

447,514

|

452,536

|

1%

|

$55,692

|

1.85

|

| Alabama |

236,259

|

238,796

|

1%

|

$49,608

|

1.44

|

| Virginia |

229,864

|

231,927

|

1%

|

$52,845

|

0.7

|

| California |

1,235,043

|

1,244,965

|

1%

|

$75,079

|

0.95

|

| Oregon |

163,179

|

164,466

|

1%

|

$60,036

|

1.14

|

| North Carolina |

431,536

|

434,259

|

1%

|

$52,551

|

1.24

|

| New Mexico |

29,019

|

29,194

|

1%

|

$53,901

|

0.41

|

| West Virginia |

49,066

|

49,307

|

0%

|

$51,340

|

0.79

|

| Georgia |

343,354

|

344,947

|

0%

|

$51,640

|

1.01

|

| Connecticut |

165,636

|

166,385

|

0%

|

$76,876

|

1.17

|

| New Hampshire |

65,760

|

66,055

|

0%

|

$62,446

|

1.23

|

| Colorado |

125,494

|

126,028

|

0%

|

$61,496

|

0.63

|

| Delaware |

26,137

|

26,120

|

0%

|

$57,090

|

0.72

|

| Rhode Island |

40,328

|

40,216

|

0%

|

$50,621

|

1.01

|

| Hawaii |

12,913

|

12,873

|

0%

|

$40,153

|

0.23

|

| New York |

455,654

|

452,083

|

-1%

|

$61,365

|

0.61

|

| Maine |

50,672

|

50,234

|

-1%

|

$50,836

|

0.98

|

| Mississippi |

135,901

|

134,099

|

-1%

|

$41,709

|

1.39

|

| Maryland |

115,097

|

113,196

|

-2%

|

$66,776

|

0.51

|

| Montana |

16,386

|

15,942

|

-3%

|

$42,569

|

0.43

|

| New Jersey |

255,906

|

247,809

|

-3%

|

$75,142

|

0.77

|

| Arkansas |

160,159

|

155,012

|

-3%

|

$40,584

|

1.57

|

| Nevada |

37,888

|

36,329

|

-4%

|

$51,492

|

0.38

|

| Alaska |

12,735

|

11,912

|

-6%

|

$42,559

|

0.42

|

| District of Columbia |

1,272

|

1,168

|

-8%

|

$97,287

|

0.02

|

Conclusion

Folks who watch the economy tend to pay a lot of attention to manufacturing. This is because manufacturing of all types and sizes produces a lot of jobs and, as export-based sectors, bring much-needed dollars into the economy.

This data offers some glimmers of hope for a very large sector that has been the constant bearer of bad news for as long as anyone can remember. More companies are opting for domestic production and the products they produce (like heavy machinery) are seeing good domestic and worldwide demand.

In this analysis some of the big winners appear to be machine shops, machinery manufacturers, audio/visual products, aerospace, foundries, metal working, and computer related manufacturing. Let us know if you’d like to learn more about any of the states or sectors we covered.

Rob Sentz is the marketing director at EMSI, an Idaho-based economics firm that provides data and analysis to workforce boards, economic development agencies, higher education institutions and the private sector. He is the author of a series of green jobs white papers. For more, contact Rob Sentz (rob@economicmodeling.com). You can also reach us via Twitter @DesktopEcon.

Illustrations by Mark Beauchamp.