A survey by TD Bank indicates that 84 percent of people 18 to 34 years old intend to buy homes in the future. This runs counter to thinking that has been expressed by some, indicating that renting would become more popular in the future. Much of the "home ownership is dead or dying” comes from short sighted trend analysis in which home ownership data begins with the start of the housing bubble in the late 1990s. The latest data from the Bureau of the Census indicates that the home ownership rate in the first quarter was 65.4 percent, the lowest rate since 1997. In fact, however, before the housing bubble, homeownership hovered generally at 65 percent or below, after having increased strongly from 44 percent in 1940 to 61 percent in 1960. The increase in homeownership during the bubble was the result of profligate lending policies that were not sustainable. The decline from the artificially high housing bubble peak in no way diminishes the successful expansion of homeownership in the nation during the decades that reason prevailed in home lending.

Blog

-

How “Public” Is the Public Sector?

You may have heard the old joke about the convenience store with a neon sign blaring, “Open 24 Hours”. A customer stops in one morning for coffee, and confronts the store’s owner, “Your sign says ‘Open 24 Hours’, but I stopped by last night at midnight for a pack of smokes and you were closed.” The owner replies, “Oh, we’re open 24 hours…just not in a row.”

I’ve been reminded of this exchange during one of the more intriguing battles over what “public ownership” means in California’s state parks. Governor Brown has designated 70 of them (out of 278) for closure in an effort to help close the state’s chronic multi-billion dollar budget deficit. In response, a Marin County Democratic Assemblyman, Jared Huffman, offered AB 42. The measure, which has now been signed into law, makes it easier for non-profits to enter into operating agreements with at least 20 of the parks on the chopping block. The law cuts the typical red-tape involved in forming such a “public-civic partnership”, including greater freedom in hiring and providing some added legal protections. And AB42 has been written specifically to hold local governments harmless from possible shoddy work, so lawsuits aren’t an issue. Over the last six months a number of parks have started making such arrangements and will continue to operate. But this is not without some consternation.

The first AB42-enabled contract has recently been signed between the previously closed Jack London State Park in Sonoma County and the Valley of the Moon Natural History Association, which will handle staffing and maintenance for this $500,000 annually budgeted facility. The Association plans to cover expenses through a mix of fundraisers, volunteer labor, and creative marketing.

Asked for her opinion on these new public-civic partnerships, state Sen. Noreen Evans (D-Coastal Northern CA) recently told The Huffington Post why she disliked the legislation: “My own philosophy is that a state park should be owned and operated by the public. Any time you turn even a portion of a state park away from public control, you always have the problem that the park’s interest becomes inconsistent with serving the public.” But this leaves open the question of what the senator means by ‘owned and operated by the public’?

Of course a state park is ‘owned by the public’ in the broadest sense, but what control do I, as a Californian, really have over how my state parks are run? In many of these AB 42 relationships between state parks and local organizations, the public is far more involved in the maintenance and running of these places than they were before.

In another issue I’ve written about, a group of parents and community volunteers were threatened with a union lawsuit if they persisted in their efforts to assume administrative tasks in a San Francisco Bay Area junior high school that had been hit with several years of budget cuts.

The local chapter of the California Service Employees’ Association (CSEA), sought to prevent parents and residents from volunteering as playground supervisors and back office staff. Said CSEA local president, Loretta Kruusmagi, “As far as I’m concerned, they never should have started this thing. Noon-duty people [lunchtime and playground assistants]—those are instructional assistants. We had all those positions. We don’t have them anymore, but those are our positions. Our stand is you can’t have volunteers, they can’t do our work.”

Notice the sense of ownership over these public sector positions. Even in the face of dire municipal fiscal situations, with stark choices between whether or not to continue services everywhere from parks to libraries, public sector unions are increasingly challenging local volunteers who are attempting to fill the gap. It is easy to wonder whom are the real “public servants” – the employees or the parents? As to complaints about the quality of volunteers, I’m not sure unprofessional behavior by volunteers outnumbers – even per capita – that by unionized/fulltime employees.

A similar story is being written currently in the West Los Angeles area Culver City Unified School District. Here, in an interesting twist on the aforementioned tale, a service union in a local elementary school is seeking to force willingly lower paid classroom attendants to unionize, and demanding that a local charity pay for these unionized positions. The El Marino Language School has been a dual language (Spanish and Japanese) immersion program for more than two decades.

A “blue-ribbon” school in California, the students of El Marino have scored exceedingly high in a number of categories . In order to keep the students “immersed”, the school began hiring native language-speaking “adjuncts” to work in classrooms for a few hours each day – usually a couple of days per week. An additional element to what the district usually supports, these positions – often filled by parents of current or former students with teaching experience – are supported by a group of local booster clubs.

The longtime program apparently escaped the watchful eye of the Association of Classified Employees (“ACE”), which represents service employees in the district. Upon learning that these non-unionized “adjuncts” were working at El Marino, ACE gave the district an ultimatum: force them to unionize or allow us to bring in our own “adjuncts”.

The current battles over how “public” libraries will be run in California casts a bright light on the use of this rhetoric by municipal unions seeking to keep out competition from private organizations. The city council of Santa Clarita, voted to withdraw from the Los Angeles County system, and contract out their three libraries to LSSI (Library Systems and Services), a private company based in Germantown, Maryland.

The response from some residents and the library employees’ union was an outcry at the supposed “privatizing” of the public library. As the New York Times reported, protest signs at the council meeting declared, “keep our libraries public”, as if access to their libraries was going to be constrained by LSSI. As then-mayor pro tem, Marsh McLean responded, “The libraries are still going to be public libraries. When people say we’re privatizing libraries, that is just not a true statement, period.”

Faced with the prospect of more communities deciding to offer library services through contracted firms, California’s SEIU lobbied the Legislature for passage of AB 438, which adds extra hurdles to city councils making these decisions. Proclaiming that they had “beat the privatization beast in California”, LA County Community Library Manager and SEIU Executive Board Member, Cindy Singer said, “By signing AB 438, Governor Brown put taxpayers and the public ahead of the profits of privately held corporations.” But, once again, knowing exactly what “public” Ms. Singer is referring to requires some circuitous thinking.

Her statement is patently untrue in Santa Clarita, where, as Atlantic Cities describes, “Hours have increased. The library is now open on Sundays. There are 77 new computers, [and] a new book collection dedicated to homeschooling parents and more children’s programs.” It appears Santa Claritans have come out “ahead”.

The macroeconomic term “crowding out” is broadly used to describe the adverse impact on private investment created by government action. The phrase also applies to the negating influence government-delivered services can have on the actions of non-profits and businesses. This is not to say that volunteers and businesses can (or should) fill all the gaps exposed by the fiscal crisis, but it may be time to consider a new phrase, as Americans assume an old role: “crowding in” anyone?

Pete Peterson is Executive Director of the Davenport Institute for Public Engagement and Civic Leadership at Pepperdine University’s School of Public Policy.

Flickr Photo by robinsan, Parking Volunteer

-

Sydney’s Long and Lengthening Commute Times

The New South Wales Department of Transport Housing and Transportation Survey reports that the average one way work trip in the Sydney metropolitan area (statistical division) reached 34.3 minutes in 2010. As a result, Sydney now has the longest reported commute time in the New World (United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand), except for the New York City metropolitan area (34.6 minutes).

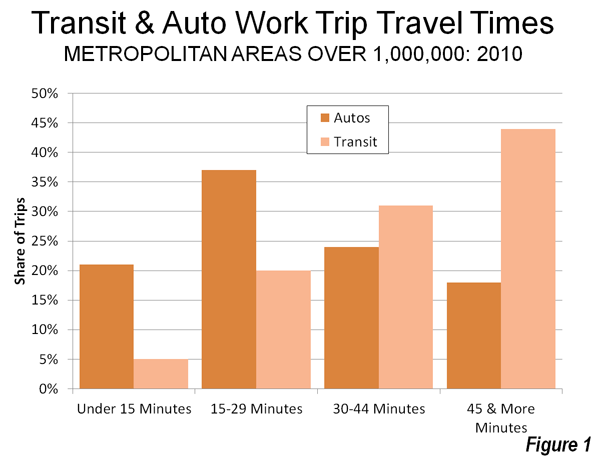

Longer Commutes than in Dallas-Fort Worth or Los Angeles: Sydney’s average work trip travel time has increased approximately 10 percent since 2002. The 34.3 minute one way travel time is approximately 30 percent higher than that of larger Dallas-Fort Worth, which about half as dense. Part of the reason for the longer commute time in Sydney is its far greater transit dependence. Approximately 24 percent of work trip travel is on transit (which is slower for most trips). This compares to approximately 2 percent of travel in Dallas-Fort Worth.

Even Los Angeles, with its reputation for "gridlock" has a shorter average commute time, at 28.1 minutes. This is made possible by the extensive Los Angeles freeway system, greater use of automobiles and more dispersed employment patterns (despite the higher density of Los Angeles relative to Sydney). The average Sydney commuter spends nearly an hour longer traveling to work each week than the average Los Angeles commuter.

Even Longer Commutes Ahead? Sydney’s densification policies (urban consolidation policies) seem likely to lengthen commute times even more in the future, given the association between higher densities and greater traffic congestion.