Jean Gottman in 1961 coined the term megalopolis (Megalopolis, the Urbanized Northeastern Seaboard of the Unites States) to describe the massive concentration of population extending from the core of New York north beyond Boston and south encompassing Washington DC. It has been widely studied and mapped, including by me. (Morrill, 2006, Classic Map Revisited, Professional Geographer). The concept has also been extended to describe and compare many other large conurbations around the world.

Maybe it’s time to see how the original has fared? And what has happened to other metropolitan complexes in the US, most notably Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago and should we say Florida?

Table 1 summarizes the population of Megalopolis from 1950 to 2010 and Table 2 compares Megalopolis with other US mega-urban complexes. Megalopolis grew fastest in the 1950s and 1960s, with growth rates of 20 and 18.5 percent. The northeast has since been outpaced by the growth in other regions, but growth was still substantial in the last decade. Megalopolis added almost 3 million people, by 6.8 %, to reach an amazing 45.2 million.

| Table 1: Growth of Megalopolis 1950-2010 | ||||

| Year | Population | Change | % Change | |

| 2010 | 45,357 | 2,983 | 7 | |

| 2000 | 42,374 | 5,794 | 15.8 | |

| 1990 | 36,580 | 2,215 | 6.4 | |

| 1980 | 34,365 | 360 | 1.2 | |

| 1970 | 34,005 | 5,436 | 18.5 | |

| 1960 | 29,441 | 4,910 | 20 | |

| 1950 | 24,534 | |||

From Table 2 I note four major subregions of Megalopolis: Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Washington, DC. New York is still the biggest player, but the locus of growth over time has shifted South. This reflects the increasing world importance of Washington, DC. New York’s almost 20 million may not surprise, but the fact that greater Boston has grown to almost 9.5 million may be more surprising. The Washington-Baltimore area grew by far the fastest at almost 15 percent (not much sign of shrinkage of government!). In contrast New York, Boston and Philadelphia’s growth was relatively paltry.

| Table 2: Megalopolis and Its Rivals | |||||

| Place |

2010 Pop

|

2000 Pop

|

Change

|

% change

|

|

| Megalopolis | |||||

| New York | 19,923 | 19,209 | 717 | 3.7 | |

| Boston | 9,445 | 8,967 | 478 | 5.3 | |

| Philadelphia | 8,415 | 76,781 | 773 | 9.5 | |

| Baltimore-Washingt | 7,403 | 7,681 | 960 | 14.9 | |

| All | 45,181 | 42,302 | 2,888 | 6.8 | |

| Chicago | 10,817 | 10,305 | 512 | 5 | |

| Los Angeles | 12,151 | 11,789 | 362 | 3.1 | |

| Central | 903 | 857 | 46 | 5.4 | |

| North | 928 | 634 | 294 | 46 | |

| East | 2,884 | 2,105 | 475 | 37 | |

| South | 3,543 | 3,210 | 337 | 10.4 | |

| All Los Angeles | 20,404 | 18,599 | 1,810 | 9.8 | |

| San Francisco-Sacramento | |||||

| San Francisco | 7,330 | 6,946 | 384 | 5.5 | |

| Sacramento | 3,171 | 2,604 | 572 | 22 | |

| All San Francisco-Sacramento | 10,501 | 9,550 | 951 | 10 | |

| Florida | |||||

| Miami | 6,027 | 5,311 | 716 | 13.5 | |

| Tampa | 4,818 | 3,894 | 974 | 25.3 | |

| Orlando | 2,915 | 2,193 | 722 | 33 | |

| Jacksonville | 1,483 | 1,191 | 2,242 | 24.5 | |

| All Florida | 15,243 | 12,544 | 2,699 | 21.5 | |

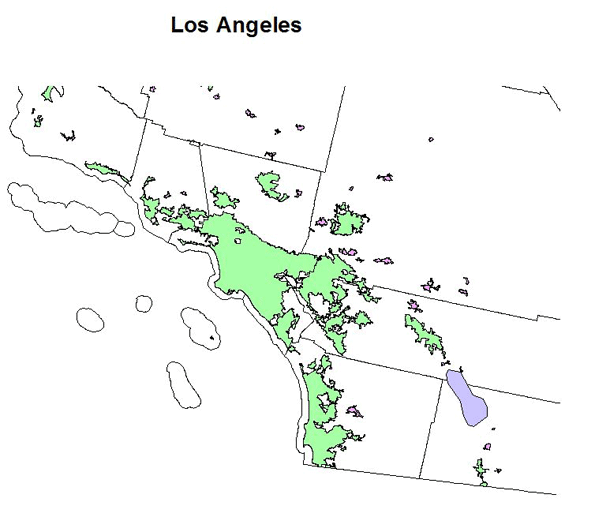

Greater Los Angeles is the second largest conurbation, with some 20.4 million, growing by 1.8 million, and 10 percent from 2000. In the table I distinguish between the core Los Angeles urbanized area and the satellite urbanized areas west, north, south and east. The core LA area grew by only 3 percent, while the spillover areas to the north and east had astonishing growth, at 46 and 37 percent over the decade. These include several places with a fairly long history, such as Riverside and San Bernardino, San Diego and Santa Barbara, but many are rapidly growing large suburbs and exurbs, a spillover of growth from the Los Angeles core. Much of the fastest growth has been in Mission Viejo, Murietta-Temecula, Indio, Lancaster, Santa Clarita and Thousand Oaks.

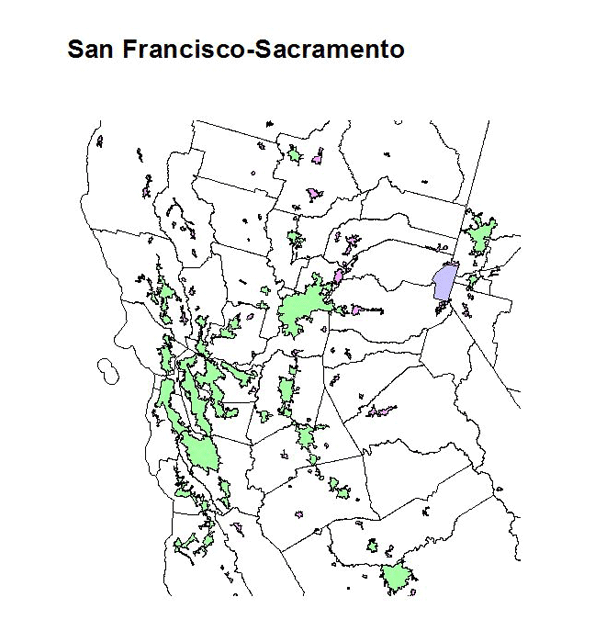

For greater San Francisco, I distinguish two subregions, the Bay area of San Francisco-San Jose (west) and Sacramento (central valley). Some might consider these totally distinct, but they have become one in a conurbation sense, as evidenced by commuting patterns. Many people live in the less costly Central Valley area but commute to the expensive Bay Area cities. Together, the conurbation is now 10.5 million, up 10 percent from 2000. The central valley (Sacramento) portion grew far more rapidly than San Francisco-San Jose (22 percent compared to 5.5 percent).

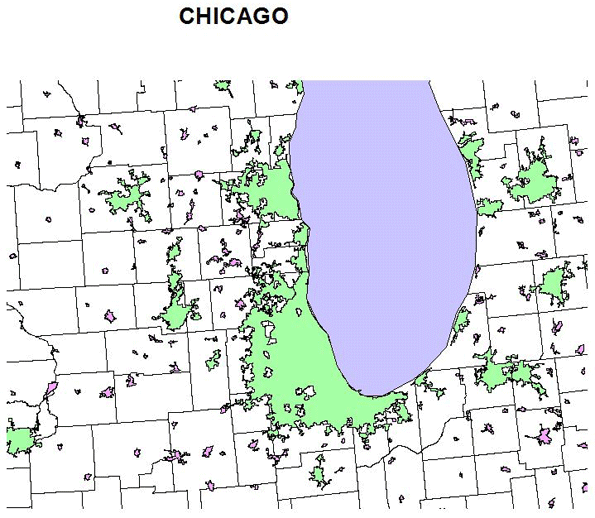

Compared to its rivals the Chicago conurbation has grown less rapidly but is still large, with a population of 10.8 million in 2010 , growing 512,000 (5 percent) since 2000. Chicago and Milwaukee are the well-known core cities, but there are also less well known components with far faster growth such as Round Lake-McHenry and West Bend, WI.

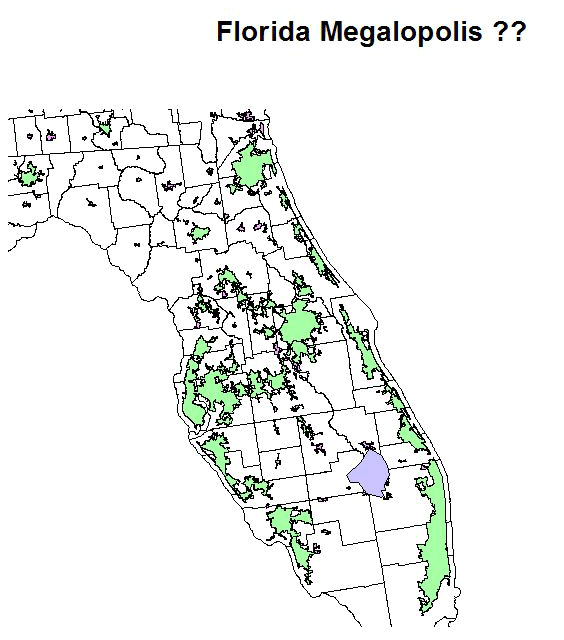

Florida

The more interesting and difficult conurbation to try to define is what might be called the Florida archipelago. Greater Miami has long been recognized as a conurbation, but I contend that virtually all the urbanized areas of the state are in effect a complex web of urban settlement, with little clear demarcation. This is in part a reflection of rapid and expansive growth. Nevertheless it makes sense to recognize four sub-regions, centered on Miami, Tampa-St. Petersburg, Orlando and Jacksonville.

Together these areas have reached an astonishing 15.2 million, up 2.7 million or 21.5 percent in one decade. Because settlement is spread across the state in such a web-like fashion with no single dominant center, they constitute a newish form of urban concentration. Besides the well-known centers such as Miami, Tampa-St. Petersburg ), Orlando and Jacksonville, there are many satellite cities, often quite large. These include North Port, Cape Coral encompassing older Ft. Meyers, Bonita Springs, Kissimmee, Palm Bay-Melbourne, Palm Coast-Daytona, and Port St. Lucie. An interesting but hard to answer question is how much of Florida’s phenomenal growth is a result of transfer of people and accumulated wealth from the North (and especially from the original Megalopolis).

The United States is a large and diverse country, with many other giant cities and a vast countryside. But it is important to realize the importance of these megalopolitan areas, with an aggregate population of 102.6 million, one third of the nation’s population.

What’s next? Look for the rise of now just somewhat smaller conurbations such as Houston, Dallas, Atlanta, Minneapolis, Seattle, Phoenix, and Denver. In terms of numbers and rates of growth Texas is a front runner, but its stars do not coalesce into a megalopolis, at least not yet. The belt of urban growth from Atlanta, through Greenville, SC, Charlotte to Raleigh-Durham is also a likely future conurbation candidate.

Richard Morrill is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Washington. His research interests include: political geography (voting behavior, redistricting, local governance), population/demography/settlement/migration, urban geography and planning, urban transportation (i.e., old fashioned generalist).